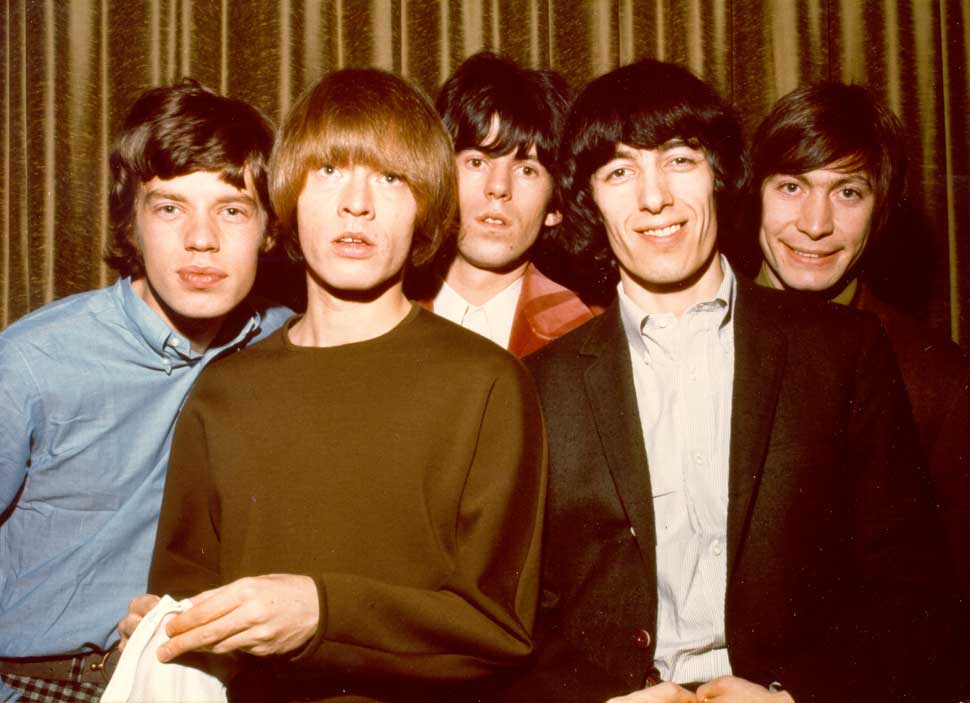

My choice of Brian Jones as a major influence on my life was determined by two criteria. The first and most obvious is that the man was one of the founding fathers of that (then) rebellious group The Rolling Stones, who challenged the supremacy of those nice boys The Beatles. The second deciding factor was that Brian was not only born in my home town of Cheltenham but also close to two members of my family, and, perhaps more importantly, our paths crossed before I was seven. Even though I was a young child, this encounter still remains indelibly etched in my memory.

Much has been written about the curious figure of Brian Jones, but very little of it sheds any light on his complex personality and his pre-Stones era in Cheltenham (although he undoubtedly had an unhappy childhood as pointed out by members of my family and several of his school friends).

Despite Brian’s early struggles, the young teenager was selected for the dismal establishment of Cheltenham Grammar School, which at that time was situated in the lower High Street. After a few years it became apparent to the school authorities that Brian, although highly intelligent, was a difficult and rebellious character.

Consequently Brian was put in a special class for bright drop-outs and awkward kids where he met fellow classmates Big Stan, Richard Winterburn, Ian Standing and my uncle Bob Pandy. The four of them formed a skiffle group and practised in the basement of my grandma Pandy’s house in Belmont Terrace off Portland Place. Their instruments consisted of one guitar (Big Stan), a tea chest with a plank of wood for a neck and one string [used as a bass], Grandma’s washboard and various cymbals that Brian constructed out of tin cans.

Uncle Bob remarked not so long ago that Brian could get a good sound out of any instrument he picked up. This gift Brian would later take with him throughout his career with the Stones, exemplified by his sitar work on Paint It Black.

My Grandma Pandy was close to Brian. He trusted and confided in her, referring to her affectionately as ‘his pal’. With Brian, the bad-boy image of the Stones was by no means contrived when we look at some of his earlier behaviour patterns. Cliff, another friend of Uncle Bob’s, remembers Brian breaking into gas meters with a crow bar in order to extract a booty of shillings. Uncle Bob referred to him as a thief, but grandma Pandy called him (in broad Cockney) a ‘randy bantam’!

My mother was more explicit when I questioned her on this. She described Brian as bright, a possible sex addict and occasionally malicious. I pushed her for more details. Ma C replied that he would go with anything – he was a womaniser with an insatiable appetite. I personally could not find anything wrong with this. Then she said Brian [allegedly] once got a mentally handicapped girl pregnant. As there was no proof, I dismissed such accusations as gossip born of legend, as I have had similar nonsense directed at myself.

When asked about his malicious tendencies, my mother said all four friends – Bob, Stan, Richard and especially Brian – used to torment a boy in their class who had a stutter and epilepsy. (Uncle Bob simply referred to this boy as a creep.)

I recall an incident around Christmas 1966. My Uncle Bob took me to the Waikiki Club in Cheltenham’s Montpellier district. I remember seeing many bizarrely dressed individuals, most of whom my Uncle Bob seemed to know. This was not so unusual, as both Uncle Bob and Auntie Ananda had often taken me to strangely dressed friends who lived in decadent regency flats with ornately corniced high ceilings and wide balconies that opened out onto tree-lined crescents; peeling walls always seemed to be covered with psychedelic posters. I remember the smell of joss sticks and patchouli. The 60s were exploding, unbeknown to me.

Inside the Waikiki Club, Uncle Bob, with myself in tow, manoeuvred around the crowded bar to an empty table by a solitary fruit machine. Uncle Bob ordered a beer and a juice. It was then that Uncle Bob and myself became aware of a commotion at the other end of the club. Six or seven long-legged, long-haired beautiful women surrounded a grinning blond dandy-esque figure wearing a battered top hat, a cravat and a brightly coloured waistcoat (my Uncle Bob’s clothes, as I was to learn later). Brian saw Bobby and pushed his way past his admirers to greet my peeved uncle. To my utter surprise Brian Jones picked me up and sat me on top of the fruit machine (much to Uncle Bob’s exasperation).

“Waiting for Father Christmas to come?” asked Brian.

“I don’t believe in Father Christmas,” I replied, embarrassed.

“Do you believe in magic?” he asked. “No,” I replied.

“You will one day,” was his answer. He lifted me to the ground and continued talking to Uncle Bob.

That was all Brian ever said to me, yet I take the memory of his enigmatic reply with me throughout my life. Maybe I read too much into it in retrospect. I wasn’t allowed to go to his funeral, but Auntie Ananda told me about the guitar-shaped floral wreaths at St James Church.

Years later, in 1984, I spent time with Astrid Wyman at the Vale in Chelsea, and the subject of Brian came up. When I mentioned the rumours surrounding Brian’s death, Astrid let me know in no uncertain terms that this was a taboo subject in the Stones camp. There was definitely something weird about her response. It is clear in my mind that people higher up the food chain knew about the circumstances surrounding Brian’s death long before the case was reopened.

Despite many of the negative aspects of Brian’s character, there are other factors to be taken into consideration. Grandma Pandy would never have become a mentor to someone who was intrinsically bad. I know she would have sensed both his gift of creativity and his vulnerability.

Brian Jones was also a mystic. I remember another conversation with Bashir – the leader and last surviving original member of the Master Drummers Of Joujouka when we were labelmates on Philip Glass’s Point Records. Bashir recollects Brian’s enthusiastic participation in the ceremonies of these frenzied percussionists’ playing, chanting and recording. Bashir also agreed that Brian was both sensitive and vulnerable. Bashir remembered one time how Brian was visibly upset when a white kid goat was slaughtered for a feast. Apparently Brian said: “That kid is me.”

His premonition was correct, and he was dead within the year.

For myself the magic happened when I rearranged Angie for Mick Jagger to sing with the London Symphony Orchestra. Stones producer Chris Kimsey told me that Keith Richards had used this version for his daughter’s wedding! I dedicated it to Brian for his amusement (all things considered).

Each year I always make a pilgrimage to Ourika (40km outside Marrakech in Morocco) where I stay at the house where the Stones used to hang out. There are many photographs of Jagger, Richards, Anita Pallenberg and Brian on the walls. The interior of the house has hardly been changed since the 60s. I always take with me an array of cheap musical instruments bought in the souk. Yes, Brian Jones inspired me to pick up any instrument and get a good sound out of it.

When I periodically return to Grasshopper Green, the house I was born in, I look fondly at the pock-marked oak floor and think of the young Brian going nuts. Then I remember Killing Joke playing full blast in the very same room in 1979.

Yes, Brian Jones was an influence on me. The dead live by love.