Jean Michel Jarre’s studio on the outskirts of Paris is a technophile’s paradise. A mixture of analogue and digital equipment, there are gadgets here dating back to the 1920s, including an early Theremin, a VCS3 Putney synthesizer as employed by Pink Floyd and Todd Rundgren, a modular Moog of the sort that Keith Emerson and Tangerine Dream would have used, and an original Fairlight CMI. Jarre is now officially the fourth musician to boast to your man from Prog that he owned the first ever such sampling device, the others being Trevor Horn, Lol Creme of 10cc, and Thomas Dolby.

According to the French synth whiz, though, that honour actually belongs to him and Peter Gabriel. “Trevor might have been the first in the UK to own one, but Peter and I had the first ones in Europe,” he confirms. “It was unbelievably expensive,” he adds with a chuckle, “but I got a discount.”

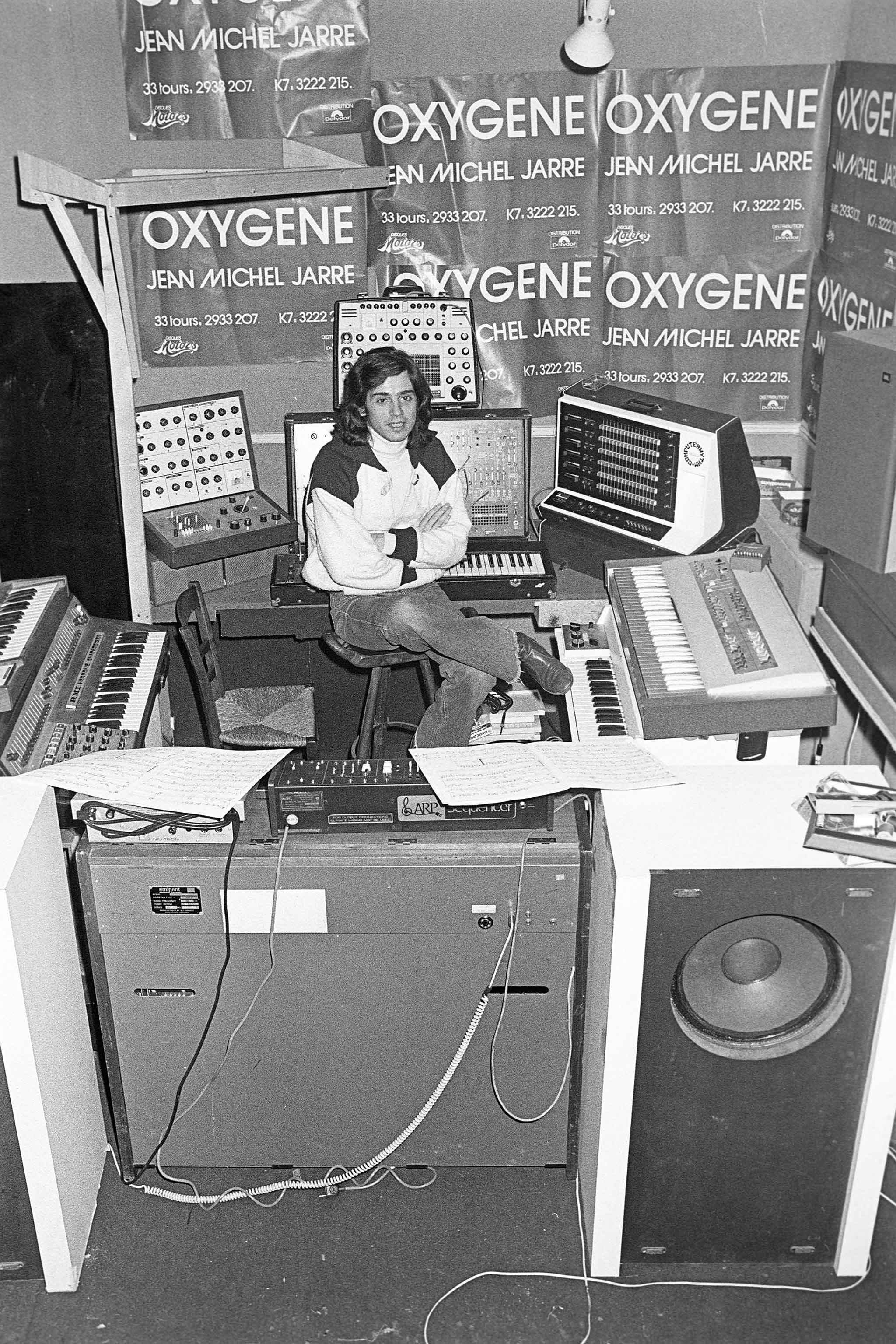

Not that he needed it (the discount, not the computer). With an estimated 80 million albums sold – 12 million alone for 1976’s pioneering work in the field of swirling, enveloping electronica, Oxygène, France’s best-selling album ever – Jarre has never been strapped for cash. In fact, he could probably have retired, but instead he went on to break more records, often with his live specials.

I wanted to create the sound of the moon. This was the revolutionary aspect. The palette of sound was entirely changed by the synthesizer.

You may have heard of them – many have entered the history books. There was the one on Bastille Day in 1979, where he drew more than a million spectators to the Place de la Concorde as he bathed the city in music and lights, images and fireworks. It was the largest ever audience for an open-air concert, while over 100 million watched it live on TV.

In 1985, following a show in Houston, Texas, he entered the Guinness Book Of Records for making a spectacle of the city’s skyline in front of 1.5 million. Not long afterwards he played to a million – including the Pope – in his home city of Lyon, and in 1990 he smashed his own record when two million attended a ‘gig’ (too paltry a word, really) at La Défense in Paris.

But even that event was dwarfed by 1997’s performance at the Moscow State University, viewed by 3.5 million, earning Jarre another gong from Norris McWhirter et al. There have been satellite link-ups with astronauts and concerts at the pyramids in Egypt, watched by two billion on TV. If anyone was going to rest on his laurels, it would be Jarre.

Instead, he has continued to release highly regarded records such as Equinoxe (1978), Magnetic Fields (1981), Zoolook (1984), Rendez-Vous (1986) and Metamorphoses (2000) that have earned him plaudits from the progressive community, as well as the dance one, who have hailed him as the godfather of techno and trance.

Now he’s bringing his ambitious approach to bear on Electronica 1: The Time Machine, an album (with a second volume to follow next year) comprising collaborations with fellow electronic music voyagers. They include Pete Townshend (whose seminal synth work from 1971, Baba O’Riley, and operatic opuses Tommy and Quadrophenia proved influential on Jarre both musically and visually), plus Vince Clarke, Gary Numan, Air, Massive Attack, Laurie Anderson, the late Edgar Froese, and even film directors and sometime composers John Carpenter and David Lynch.

“I’ve had this project in mind for a long time,” says Jarre, tidying up his studio following a photo session.

He explains that rather than just sending files back and forth, he travelled to each and every one of his collaborators. “That’s why it took me four years!” he says with a laugh. “I went to Vienna to spend time with Tangerine Dream, to Berlin to meet Boys Noize, to Richmond for Pete Townshend, to Bristol for Massive Attack, to Brooklyn to meet Vince Clarke, to LA to work with Moby, Gary Numan and David Lynch, and Paris with Air.”

For each of the encounters, he went armed with a camcorder (“in an Andy Warhol way”) to record each tryst for a forthcoming documentary. From Townshend to Moby, whom he describes as “the Woody Allen of techno”, he chose his collaborators because each had an instantly recognisable signature – giving the lie to the idea that electronic music is anonymous – and because he respected their work. Turns out they were equally big fans of his.

We opened the door onto virgin territory. We had nobody before us so we could explore with innocence and unconsciousness.

“I’d never met anyone so famous – it was quite surreal,” says the normally taciturn Vince Clarke, beaming during his filmed segment, and marvelling at the prospect of working with a childhood hero. He adds: “Our interest in electronic music is an obsession.”

But how to classify it? Jarre wonders where Electronica 1 will be categorised in the world’s remaining record stores. “It hijacks different genres,” he decides. “You could put it in the trip-hop section because of Massive Attack, in techno because of Boys Noize, in electronica with Air or in trance with Armin van Buuren. It’s very interesting.”

Despite his extracurricular visual forays, Jarre considers himself “first and foremost a musician”. With his MacBook Air ever-present, he’s the original solo electronicist: a proto-laptop boy or EDM kid. Now 67 (although he looks a good decade younger), he has had a varied career. As a classical-oriented teen he studied harmony, counterpoint and fugue before learning various instruments (electric guitar, flute) and exploring the possibilities of tape effects and other experimental sounds. He joined the Groupe de Recherches Musicales in 1969, under the tutelage of musique concrète major-domo Pierre Schaeffer. He even spent time working at the studio of German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen in Cologne.

His avant-garde credentials are solid, as is his reputation as one of the few – along with Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Vangelis, Tomita and Giorgio Moroder (not forgetting Rundgren/Stevie Wonder) – who helped popularise the synthesizer and electronic music in general.

“I was always convinced that electronic music was the future,” he declares, “because it is beyond a genre. It’s not like hip-hop, punk or rock – it’s a new way of conceiving and producing, writing and distributing music. Anything from Kraftwerk to Avicii is electronic music. It just shows how wide the electronic music umbrella is.”

How different would today’s EDM-scape look had he not existed? “Mick Jagger was asked at the start of the Stones, ‘How long do you think you will last?’ and he said, ‘Two years would be great!’” Jarre says, sidestepping the question. “We had no idea in those days. I feel very lucky. Those people in rock like Mick, or me and Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk in electronic music, we opened the doors onto virgin territory. We had nobody before us so we could explore with innocence and unconsciousness.”

His first two albums – 1972’s Deserted Palace and 1973’s soundtrack to the movie Les Granges Brûlées – were all but ignored. Even Oxygène was initially met with resistance.

“It was refused by almost all the record companies,” he recalls, doing an impression of an aghast music industry employee. “‘What do you mean it has no drummers, no singers and it’s in French? Who’s going to buy that?!’”

Apparently, because of the white noise at the start of Oxygène, copies were returned in their thousands, listeners presuming it was a technical fault. “This was something new, linked to a vision of the future,” says Jarre, who believes the expansionist vision of a bright, bold, new tomorrow, once held by everyone from Kraftwerk to Kubrick, has been lost and needs reclaiming.

Jarre’s conception of keyboard-based music was different to that of Messrs Emerson, Wakeman and Banks. In his view, he was coming from a purely European classical tradition, whereas his prog peers were “using synths in the context of rock music”.

Nor, he insists, can comparisons be drawn between himself and Mike Oldfield, that other photogenic wunderkind with a stratospherically successful 70s album: Oldfield circa Tubular Bells was entirely acoustic, even if the hypnotic and repetitive music sounded electronically sequenced. As for Wendy (née Walter) Carlos, a heroine of Jarre’s, her Switched-On Bach was an attempt to replicate classical instruments with synths, whereas Jarre was intent on inventing new sounds. “I wanted to create the sound of the moon, whatever,” he says. “This was the revolutionary aspect. The palette of sound was entirely changed by the synthesizer.”

Equally revolutionary was Jarre’s approach to stagecraft. “I went into it all in a massive way, with massive productions,” as he puts it.

The sheer scale of his shows was unprecedented. He got a taste for the lavish with the 1979 Paris concert. It must have been overwhelming to see so many there.

“Absolutely,” he admits. “It took me a year to recover. It was all on word of mouth – I didn’t have a lot of big promotion. And there were all these technical problems to solve because of all the crazy machines around me… I couldn’t believe there were so many people. I remember backstage somebody looking a bit like Fidel Castro coming up to me and saying, ‘Man, I never saw anything like that!’ It was Mick Jagger. It was the first concert of its type involving so much technology. Pink Floyd were also doing this kind of thing but few others on that scale, outdoors.”

He could have been forgiven for becoming a rampant egomaniac, surely?

“Well, the 80s came along and we all lost ourselves,” he acknowledges. “[Putting on extravagant live shows] was like a new drug, and I became addicted.”

What do you do when three million turn up and then at your next concert there are ‘only’ 1.8 million, and the Pope?

“I’m not sponsored by Guinness [World Records],” he says of the inevitable drop-off in terms of attendance. “I don’t care really. I’m not the Usain Bolt of music shows!”

How about the Henry Kissinger? After all, he has performed in Russia and appeared on Chinese TV after Tiananmen Square. Indeed, he was the UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. He’s in a good position to effect universal rapprochement in this time of rising international tensions…

“You’re right,” he says, citing numerous examples of times when he has been invited into countries, often during moments of deep crisis. He’s wary, however, of becoming the Do-Right Man. “I’m cautious about the charity business, about the cause of the month. Sometimes I have to do things,” he says, “but I’ve never promoted this kind of action or used it for my career.”

Jarre has always had a beneficent air about him, especially in the benighted rock realm. Does that make him want to raise hell? “You know,” he says, smiling enigmatically, “I had enough of this in my private life.”

True, there have been the well-publicised marriages to (and divorces from) Charlotte Rampling and Anne Parillaud, and an affair with Isabelle Adjani. “Yes, I had a problem dealing with actresses a few times,” he says.

Are beautiful actresses his vice? “I don’t know if you can call it ‘vice…’” he replies, before changing the subject back to his multimedia extravaganzas, where he tells us all was not as it seemed.

“I could write a book on each of those projects,” he says. “The Docklands one [in 1988] was crazy. It involved Robert Maxwell and the police, Downing Street and Margaret Thatcher, the New Christian Sect and the Chief Executive of Newham Borough. And some effigies of me with needles that they found in a cellar. You have no idea! There were so many political and financial interests… Backstage was like a battlefield.”

He then extrapolates, dramatically, suggesting there might be more to the affable, suave, handsome Jean Michel Jarre than meets the eye. “It’s like Francis Ford Coppola said about The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now: The Deer Hunter was a movie about Vietnam; Apocalypse Now was Vietnam. I’ve lived a few Vietnams in my life.”

The last few years have been tough: his publisher died, as did his mother, France Pejot, “an extraordinary woman” involved in the French Resistance. His soundtrack-composer father, Maurice (Lawrence Of Arabia, A Passage To India) also passed away, and Jarre got divorced for the third time.

“Instead of four weddings and a funeral I had three funerals and a divorce,” he jokes gamely. “This Electronica 1 project has been real therapy for me.”

He describes the overall aesthetic as “dark and sunny”: upbeat melodies belying a heart of cold terror. “I’ve always liked any art form which is apparently quite happy and joyful but hides a deep melancholia,” he reveals at the end of the interview, reminding Prog of the title of his first ever composition: Happiness Is A Sad Song. “I didn’t even realise when I was making it, but listening back, it fits: ‘dark and sunny’. Without wishing to be too philosophical, that is, in a sense, my life.”

Electronica 1: The Time Machine is out on October 16 via Columbia. For more information, see www.jeanmicheljarre.com.