“We tried the spaceship at The Who’s studio. Pete Townshend saw it and said: ‘I want one!’”: How Jeff Lynne took Electric Light Orchestra and the Traveling Wilburys to infinity and beyond

ELO were the mad Englishmen who conquered the US in the 1970s – and Jeff Lynne was at the heart of it

Led by singer, guitarist and chief songwriter Jeff Lynne, ELO – or Electric Light Orchestra, to give them their full name – bestrode the 1970s like a bearded, frizzy-haired giant before splitting in 1986. In 2012, Lynne returned his old band once more with Mr Blue Sky, a solo album that found him re-recording several ELO hits. When Classic Rock sat down with him in London, he was ready to look back over his stellar career.

The hair is smaller, the beard neater, but those impenetrable sunglasses still give him away. In a changing world, there’s something reassuringly unchanged about Jeff Lynne, the one-time composer and producer of symphonic rock ensemble Electric Light Orchestra. Dressed in an understated black jacket and jeans, Lynne, a famously private man, peers out of the window of his chosen venue, a smart boutique hotel near London’s posh Sloane Square. “Most people don’t know about this place,” he says appreciatively.

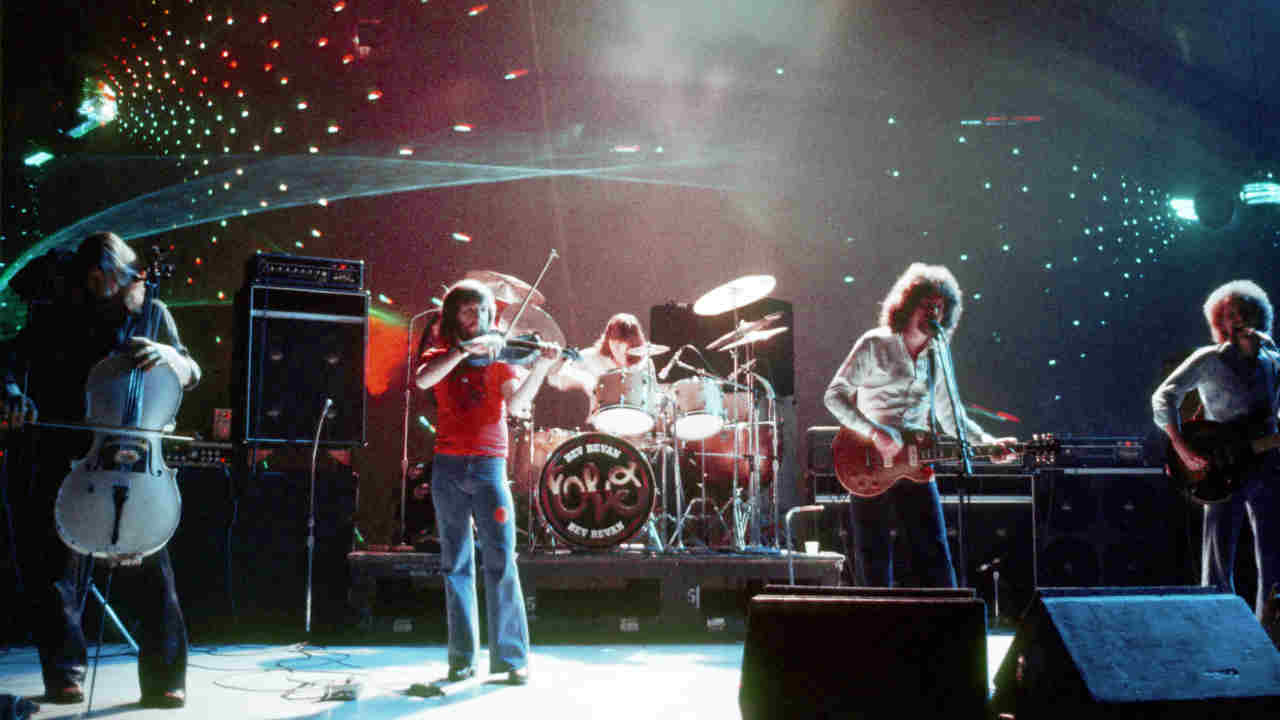

Forget punk-rock revisionism and critical scorn (“Electric Light Orchestra are technically adept, cynically presented froth,” carped Rolling Stone). ELO ruled the 1970s, with multi-platinum albums such as Out Of The Blue, and US and UK Top 20 hits with the likes of Livin’ Thing, Sweet Talkin’ Woman and Turn To Stone. In 1978 there was no one bigger. That year, ELO undertook a record-grossing US tour with a spaceship-style stage set that pumped out 525,000 watts of light and required 13 trucks to transport it from city to city. ELO were just as big in the studio: hiring 40-piece string sections and 30-piece choirs to recreate the sounds inside Jeff Lynne’s head. With their huge choruses, deluxe production and everyman lyrics, they were once likened to what The Beatles would have sounded like had they been beer drinkers instead of dope smokers.

It was apt, then, that George Harrison asked Lynne to produce an album for him in 1986. “And after that, everything changed,” Lynne says, smiling. Within months he had joined Harrison, Roy Orbison, Bob Dylan and Tom Petty in roots-rock supergroup the Traveling Wilburys. In 1995 he co-produced The Beatles’ ‘comeback’ single Free As A Bird.

Today, despite more than 30 years of Beverly Hills living, the Shard End, Birmingham-born Lynne still hasn’t lost his Midlands burr. No wonder more complex, hung-up artists, such as Dylan and Petty, like having him around. You suspect he leaves his own complexities and hang-ups at the door.

In October Jeff Lynne released two solo albums: Long Wave, a collection of mostly pre-rock’n’roll standards; and Mr Blue Sky, his new interpretations of classic ELO hits. Both aim to reproduce the extraordinary sounds whizzing around inside his head. “I love being inside a song,” he says. “So close that it’s like I can almost touch it.”

ELO were never off the radio in the 70s. Long Wave is full of the songs you heard on the radio, growing up in the 50s.

My dad had the radio on all day. There was no TV until I was 13 so all I got was his music. A lot of these songs I hated as a kid, like [Rodgers & Hammerstein’s] If I Loved You. I also never thought I’d be singing [Bobby Darin’s] Beyond The Sea. But if you listen to the strings in the middle, they sound like ELO. It’s only when I discovered how to play the songs that I fell in love with them. It’s the way they’re constructed that intrigues me. I wanted to be a record producer from the age of 13.

Why so young?

I heard Only The Lonely by Roy Orbison [in 1960] and I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. All I could think was: “How do they do that? How do they know what to play?” After that, all I thought about was music. I left school at 15 and joined a group called The Nightriders, but I still had to work. So I took a job in a warehouse where I could always go behind the bins and practise my guitar for half an hour. When I turned pro at 18 I was so relieved.

What did you think when you first heard The Beatles?

Please Please Me [The Beatles’ second single, released in January 1963] was the one. The first single Love Me Do didn’t do it for me. I don’t mean that in a bad way, but it was very simple, only a couple of chords. Please Please Me felt like it was something else entirely. It was mind-blowing.

The Nightriders later became The Idle Race. While recording their first album,The Birthday Party, in 1968 you visited Abbey Road studios and watched The Beatles making the White Album. Did you ever imagine you’d end up working with George Harrison?

Never. Not in a million years. It was like meeting your gods. But I knew I was pretty good and could make a living out of music. I had a feeling I’d never have to go to work again. I’d been asked to join [fellow Birmingham group] The Move in ’67 and I turned them down. I thought I owed The Idle Race, as they’d saved me from this awful life of working. But their albums weren’t hits, so when The Move’s singer Roy Wood asked me again I had to say yes.

As soon as you were in The Move, though, you and Wood were plotting ELO.

By the time I joined in 68 The Move were doing cabaret, and I didn’t want to be a part of that. Roy and I had been talking about the idea of ELO for months. So we made those Move albums [1970’s Shazam and 71’s Message From The Country] to help pay for ELO.

ELO’s debut LP, Electric Light Orchestra, in 1972, featured bassoon, oboe, French horn, cello… Is it true you wanted the group to continue what The Beatles had started with I Am The Walrus?

I Am The Walrus was a big influence because of the cello parts, true. So was A Day In The Life. But I never said we were picking up where The Beatles left off. I get the blame for that, and I never said it. It was Roy Wood. At the time I thought, oh fuck. Now I think, fucking great, Roy, you’ve saddled me with this for years! [laughs]

You once described the early ELO gigs as “shambolic”. What went wrong?

Everything. We did our first gig at The Greyhound in Croydon. It was horrible, dreadful. It was amazing how Roy taught himself to play the cello in a week, so he could play it on our first single, 10538 Overture. But on stage it took him forever to change instruments because he was also playing the bassoon and the oboe. And we couldn’t hear ourselves properly. We used to have to get a little drunk just to take the edge off. Then I did something wrong.

What did you do?

It was the third ever ELO gig, in Liverpool. I’d had a drink and I needed to take a piss. There was a big curtain behind the stage dividing the room in half. So I went behind it and called to my roadie Phil to get us a bucket. He came back with this great big cleaner’s bucket and held it up for me. I was playing bass, and all I had to do was play an open-string A on the song we were doing. So I was playing with one hand and piddling into this bucket. But it just went on and on. I’d not finished when Phil moved and it was all up his arm [laughs]. I never did it again after that.

Why did Roy Wood leave ELO so soon?

Roy and I didn’t collaborate as well as we thought we would. We couldn’t work together. It was like having two individual bosses in the band. So he went off to do [Wood’s next group] Wizzard, and I got to be the sole writer and producer of ELO.

When did ELO start getting better?

About six months after Roy left. We made the second album [ELO II], and that had [a version of Chuck Berry’s] Roll Over Beethoven on it. It went Top 40 in America. So suddenly we’ve got our foot in the door over there. But I always remember my dad saying to me: “The trouble with your tunes is they’ve got no tunes,” because he didn’t think much of my songs. So I thought, I’ll show ya. And I wrote Can’t Get It Out Of My Head, a tune that was full of tunes. We put that on the fourth record, Eldorado, which sold half-a-million and went gold in America.

Growing up in a suburb of Birmingham in the 50s, you must have dreamed of going to the States.

It was a very big deal. The Idle Race had been on United Artists, and on their record labels it used to say ‘United Artists, Sunset Boulevard’, with a picture of a street with palm trees. And I used to think: “God, I want to go there.”

The first time we went to the States was supporting Deep Purple [1974]. They were playing 10,000-seater ice hockey stadiums. You could see the audience looking at us with our cellos and thinking,: “What the hell is this?” But they liked us. So it took off there, even before the UK.

ELO were managed by Don Arden, father of Sharon Osbourne, and a man nicknamed The Al Capone Of Rock. How was he to work with?

His reputation precedes him, yes. [Long pause] I don’t know if he was a good manager or a bad manager. He got us there. I always had the studio time I wanted. He helped make us successful. So I owe him that. But he had his flaws. He was good and bad.

Was there a particular point when you realised ELO had made it?

In America. After a while we started doing the 20,000-seaters. We were driving in a limo up La Cienega towards Sunset Boulevard, and there was this great big billboard that said ‘Welcome ELO’. I thought: “Fuck, this is good.” The record label had put us to stay in the Continental Hyatt House, which used to be called the Riot House after John Bonham or someone rode a motorbike around the top floor. And there was another sign saying ‘Welcome ELO’ outside. That’s when I felt like we’d made it. But after that it just got bigger and bigger.

Did you do all the things rock bands were supposed to do when touring America? Was there such a thing as an ELO groupie?

Yeah, there were ELO groupies [looking surprised]. But we only ever wrecked one hotel room. We played Washington, and the president Jimmy Carter’s son, Chip, came to the gig and invited us to visit the White House the next day.

I dunno why, but after the show we ended up trashing somebody’s room. We piled all the broken furniture in a heap in the middle like we were going to have a bonfire. Then we looked at it and panicked. I always remember someone saying: “Shall we leave now under the cover of darkness?” We didn’t. But when we left the next morning, we saw Sharon [Osbourne] in reception and she was paying the bill, and it was 10,000 dollars cash. We all went: “Oh fuck,” and ducked out before anyone could see us. We didn’t do it again.

ELO were a seven-piece group, with two cellists and a violinist. How difficult was it to keep seven people on the road happy?

There were two separate camps, y’see. There was us – we were the rock’n’roll players – and then there were the string players. We got on okay, but they had a different mentality. They weren’t in the clique. They weren’t rock’n’roll people – they’d all come from string player’s college.

On stage you always looked like you were a reluctant frontman, though.

I didn’t want to be there, no. I enjoyed the first two or three tours, but after that I was out of joint with it. I just wanted to be at home, writing and recording.

Did ELO compensate for that by using so many special effects in their live shows?

I was compensating, I suppose. Any idea that was really daft, I’d say: “Oh yes, we’ll have that.” Our cellist Mike Edwards had this idea for playing [French composer Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns’s] The Dying Swan while rolling an orange up and down the neck of the cello. Then he had a cello that exploded on stage. Mind you, sometimes it exploded, sometimes it didn’t. It was good when it worked properly. Mike, unfortunately, later got killed by a bale of hay [after it fell on to the roof of a van he was driving, in 2010].

ELO’s 1976 album A New World Record went to No.1 in the US. A year later Out Of The Blue was top five in the US and the UK. Next, ELO were touring with a spectacular, spaceship-style stage set, and US opening acts that included Heart, Journey and Meat Loaf.

We were doing 70,000-seaters in some parts of America by then. But the shows were getting too big for me. The spaceship was Don Arden’s idea. We first tried it out at The Who’s studios in Shepperton. Pete Townshend came in, saw it and said: “I want one of them!” The spaceship was amazing – the noise it made at the end of the show was incredible, like rocket engines. I used to dash out to the front and watch from the audience. It was Don who got Tony Curtis to introduce us on stage at Wembley that year, where we played to royalty [the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester]. But I was more impressed at the reception afterwards.

Why was that?

They’d put all our gold discs up on the walls at the reception. I kept thinking: “This looks impressive. These are for songs I’ve written.” That was the problem: I just wanted to be in the studio. Touring cramped my style.

ELO’s music has a reputation for being upbeat, but hits such as Telephone Line sound extremely sad. Were you having a really miserable time of it?

I always thought our music was sad. Whenever people say: “Wow, your songs makes me feel so good,” I think: “Hold on, I’m writing about loneliness.” [Laughs] Telephone Line is the saddest of them all. It was written just after an American tour. I’d got a girlfriend over there and she wasn’t answering the phone. That’s why I used the sound of the American dialling tone. It was all about long‑distance telephone calls. Touring played havoc with relationships and anything like that.

Which is the greatest ELO album?

Out Of The Blue would have to be one of them. My favourite now, though, is On The Third Day, after I realised what a cheeky bastard I’d been. I had all the music plotted out, but there are two or three songs where I hadn’t written any words. So I just stood in front of the mic and sang the first thing that came into my gob. And I was amazed when I played it again, as it sounds pretty good. A lot of ELO songs are simpler than you might think. I could show you how to play Mr Blue Sky in 10 minutes. It’s no symphony.

ELO split in 1986, and then you were asked to produce George Harrison’s next album, Cloud Nine. How did that happen?

I‘d had enough of ELO. It was a relief to do something else. I’d been doing some recording with Dave Edmunds, and we had just finished dinner in a restaurant in Marlow. He was about 200 yards down the street when he shouted back: “Oh, Jeff… by the way, George Harrison asked if you would like to work on his new album.” For fuck’s sake! We’d spent two hours having dinner and he never mentioned it.

Were you intimidated by meeting George?

I was intimidated by George’s house [the 120-room Friar Park in Henley-on-Thames]. It was like a mansion, a castle and a palace all rolled into one. When I first turned up there I thought: “I don’t know if I can do this.” I was that worried it was going to be too posh. But George put me at ease. He said: “Look, before we start, just so we can see how we get on, shall we go to Australia to watch the Grand Prix?” I said: “Er, yeah, alright.” He said: “Great. Meet me in Hawaii in two weeks’ time.”

So 18 years after you’d watched The Beatles making the White Album, you were working with one of them.

I know [laughs]. But I didn’t feel intimidated about making suggestions in the studio. That’s what George wanted me for. But you could ask him about The Beatles’ records and he’d tell you stuff. Like how Please Please Me had been really slow to start with, like a Roy Orbison record, and George suggested they speed it up.

Who came up with the idea to put together the Traveling Wilburys?

One night, George and I had a bit of a smoke and a drink, and he said: “You and I should have a group.” I said: “Who should we have in it?” “Bob Dylan,” he said. “Oh yeah, okay… Bob Dylan… What about Roy Orbison as well, then?” And we both suggested Tom Petty. I didn’t imagine it would actually happen. But it did. We did the first Wilburys’ song, Handle With Care, in Bob’s garage.

What’s Bob Dylan actually like?

Bob’s a normal guy, friendly, not aloof… But he’s on his own wavelength. I mean, it’s Bob Dylan, so you are always a bit in awe. I kept thinking: “He wrote all those words [laughs].”

After The Traveling Wilburys, you produced Tom Petty’s first solo album, Full Moon Fever. Petty said that your arrival upset his group The Heartbreakers. Did you sense that?

A little bit, yes. But I was only interested in Tom. He’d asked me to write with him and produce, and that was all I cared about. Free Fallin’ was the second song we wrote for that album, and it was a huge hit. Full Moon Fever came together so easily. It is still one of my favourite records of all those I’ve worked on.

You’ve just re-recorded and remixed some of ELO’s biggest hits for the new collection Mr Blue Sky. What was wrong with the originals?

There was no clarity to them. They sounded like they had a sock over them. It was bugging me whenever I’d hear them on the radio. I didn’t have much studio experience when I produced the originals. Now I’ve had 30 years more experience and technology is 30 years ahead. So I tried doing Mr Blue Sky again and it sounded so much better. Then I did Evil Woman, Strange Magic, and I ended up doing 17 of them again, but we got it down to 12 for the album.

You can’t stay out of the studio, can you?

No [laughs]. They have to come and drag me out. But it’s what I do. I’ve enjoyed making these two albums more than anything I’ve ever done before. In the studio I can just block everything out. I walk in there, shut the door, sit down and think: “Ah… this is the fucking life… Happiness.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 178, November 2012

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.