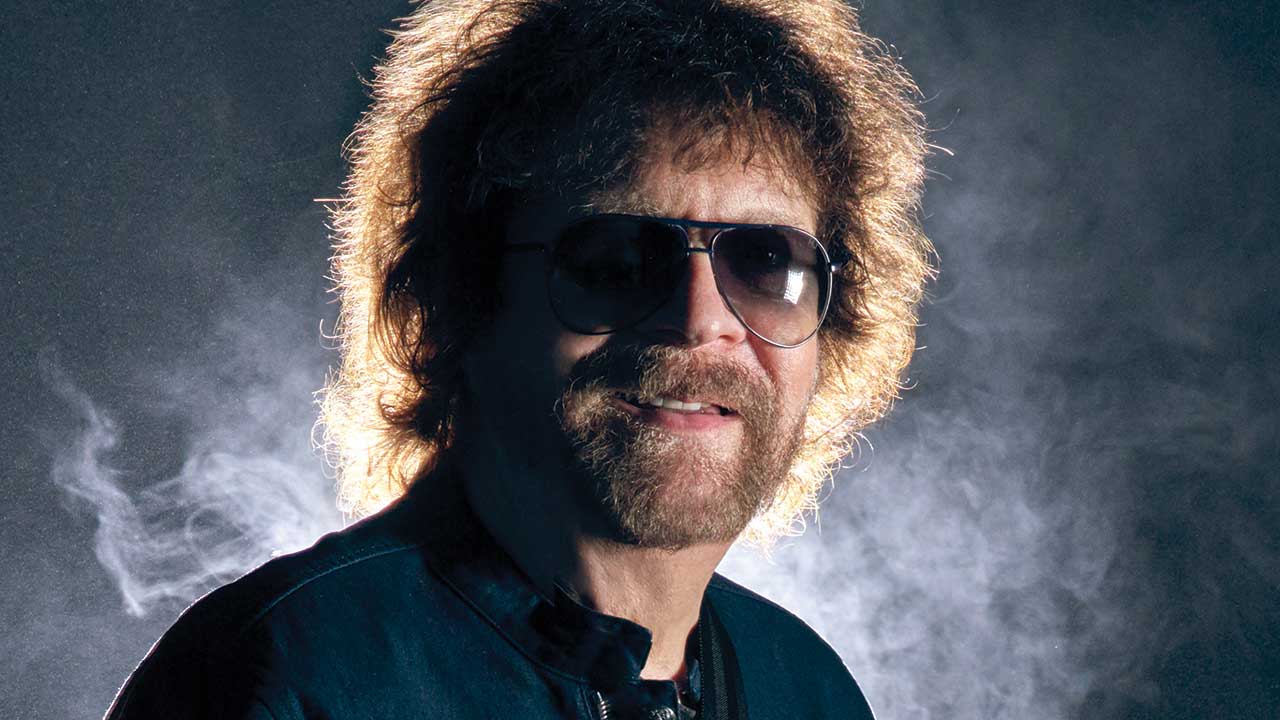

Jeff Lynne interview: from ELO to The Beatles and into the blue sky

Jeff Lynne looks back at a long and hugely successful rock’n’roll career, one that has seen him lead ELO, work with The Beatles, and be in a band with Bob Dylan and Tom Petty

“I was worried that there weren’t enough people who knew about us,” says Jeff Lynne, explaining his anxiety over reviving ELO to headline at an all-day festival in London’s Hyde Park in September 2014.

“We took a big chance. The crowd could’ve gone home any time, they didn’t have to wait around for us at the end. But it was still full. I remember looking through a little gap in the curtain and going: ‘They’re still here!’”

Of course they were. The festival was a sell-out, shifting its full quota of 50,000 tickets in just a quarter of an hour. It seems ridiculous that one of the most bankable stars of all-time ever doubted he still had an audience. But then Jeff Lynne isn’t your typical rock star.

Modest and self-effacing, it’s difficult to equate the soft-spoken 71-year-old – his Brummie accent still intact despite living in Los Angeles for many years – with his status as the head of ELO, with record sales of well over 50 million and counting. Indeed, from 1972 until their original dissolution in 1986, ELO scored more transatlantic Top 40 hits than any other band on the planet.

There’s more to Lynne than just ELO, of course. Since emerging with the Idle Race in the late 60s, the singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist has passed through The Move, co-founded supergroup the Traveling Wilburys (with Bob Dylan, George Harrison, Tom Petty and Roy Orbison) and produced a host of A-listers, including the three remaining Beatles, both on solo Out Of Nowhere, is essentially a one-man operation.

It’s a sumptuous addition to his extensive recorded catalogue, bursting with semi-symphonic goodness and melodies to melt the stoniest of hearts. “Chords are my favourite thing, really,” Lynne enthuses. “There aren’t many left, but I still keep stumbling across little strange quirky ones and big fat juicy ones. Finding them is so much fun.”

What’s the story behind From Out Of Nowhere?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The title track just literally came from out of nowhere. It was the first tune I sat down to write, and nearly all the chords came to me at the first sitting. And that’s really how the whole album came around. I wanted to put some kind of optimism in there too. It’s a reaction to the way things are in the world at the moment; it’s a very upside-down situation. At the same time, I didn’t want to get into politics whatsoever.

One of the new songs, Time Of Our Life, is about ELO’s Wembley Stadium show in 2017.

It’s like a diary of the Wembley show, which turned out to be absolutely fantastic, because I was still worried about trying to fill up these great big places. But there they all were. I’d played there with ELO once before, about thirty-odd years ago [in July 1986, supporting Rod Stewart], but I’d never done it as top of the bill. Everyone seemed to be having a fabulous time. It was just a marvellous experience.

Some of the songs on From Out Of Nowhere have a wistful quality to them, such as All My Love and Down Came The Rain. Do you find yourself looking back more nowadays?

I think I always have done, actually, even in the early days when I had nothing to look back at. It was just the old-fashioned music that I used to hear my dad playing on his record player or on the radio. I don’t really dwell on the past, but I try to make a certain type of music that encompasses chord changes that feel almost classical.

Great songs by [musical theatre composer of the 1920s/30s/40s] Richard Rodgers, for example. I could never understand them as a kid, because there was so much going on in terms of arrangements, but I wanted to be able to play some of those changes. Hearing two chords joined together, ones that really want to be there, is just a beautiful sensation.

Were you influenced by your dad’s taste in music?

His favourite composers were classical. He couldn’t read or write music, but he used to be able to play Chopin on the piano with one finger. My dad didn’t encourage me that much, but he bought me my first guitar for two pounds, so I had a good initiation, until my fingers bled. Then I got him to sign the papers on an electric Burns Sonic and a ten-watt amp

Growing up in post-war Birmingham, the job prospects were slim. Was music an escape?

Absolutely. There was nothing I wanted to do in the work field, but I did work in a few offices. I had about fourteen jobs in two and a half years. Some of them lasted less than four hours. One job was as a window dresser in this big department store, which I got through the youth employment office. I was only fifteen or sixteen at the time. You had to put these dusters on your feet and go into the window at C&A in Birmingham. I was thinking: “What if one of my mates comes past?!” I lasted until noon, then I snuck out the back way. I never went back.

There were lots of other silly jobs as well, some of them very nice and some were grim. But you have to go through it. Then I got a phone call from [singer/drummer] Roger Spencer of The Nightriders. I went for the audition, got the job, and I was a professional musician at the age of eighteen. It wasn’t long before we changed our name to the Idle Race.

How high were your ambitions in the Idle Race?

I probably would’ve been happy enough just playing club gigs in Birmingham. There were so many of them that you could play a month straight without repeating yourself. You’d play every night of the week and, for a couple of years, every night of the year. It was a great experience and a great way to learn. Then I started writing my own stuff, and it just developed from there.

When did your Beatles’ fandom begin?

Right from the start. Please Please Me turned me on to them and I became a really great fan. I’ve had lots of luck when it comes to The Beatles. When I was recording with the Idle Race in London in 1968, a friend of our engineer phoned the studio to say he was working on a Beatles session at Abbey Road. He told us we could go down there to have a look if we wanted.

Maybe it was only me who went in the end, but I saw Paul and Ringo in Studio 3, doing a piano and vocal. Then I got invited into Studio 2, where John and George were in the control room. Down below, in the actual studio, George Martin was hurling himself around this pedestal, conducting the string section for Glass Onion.

I was blown away. Nobody had heard it yet, but there I was in Abbey Road, actually listening to it being made. I stayed for maybe half an hour, then I thought it would be polite to leave, because you feel a bit of a dick in that company. So I went back to where the Idle Race were recording and, of course, it didn’t sound quite so good.

Was joining The Move a stepping stone to ELO for you?

The Move weren’t as famous as they used to be when I joined. It was okay, but we didn’t really do anything good or play anywhere other than little clubs. We joined to make ELO. That’s what Roy [Wood] and I were attempting to do. But it didn’t work out, and Roy left after less than a year after we’d started ELO.

The gigs were a real mess; you couldn’t hear the cellos, because they only had microphones for the string instruments at that time, rather than pick-ups. I don’t know what it sounded like for people in the audience, but it didn’t sound particularly good from where I was standing. I’m still friends with Roy and I see him every now and again, every time we play Birmingham or wherever.

Many of those great early ELO songs, like Showdown, were written in your parents’ front room, right?

True. I had a studio in the front room at that point, where I’d record those old ELO tunes. It was right by the bus route, so I used to get these giant buses rumbling through my demos. Then I’d send them off to the record company.

There’s a story about Beatles producer George Martin popping in to listen to ELO recording Roll Over Beethoven at AIR Studios in 1972. He was doing Paul’s Live And Let Die in the studio next door, so he came in and gave Roll Over Beethoven a thumbs-up.

He actually sat and listened intently to it all the way through, because it was a bit of a strange arrangement with all those classical things in there. It was a great experience, and I got to know him a little bit then.

ELO’s 1976 album A New World Record was a massive international hit. Was that the turning point for ELO?

I think it was. Just prior to that, we’d had two really big hits with Evil Woman and Strange Magic, both from Face The Music [1975]. We’d got a different line-up together and started doing these American tours, which turned out amazingly well. We seemed like such a strange group for an American audience, with two cellos, a violin, Mellotron and a bit of French horn. It was just an odd sound.

The first tour was supporting Deep Purple, which you wouldn’t think would be a good match, but we went down great. So we started touring America on our own and it just gradually built up from there. I think the biggest one was in Cleveland, in front of about sixty thousand people.

The following year’s Mr. Blue Sky is one of your most enduring songs. Among other things, it became Birmingham FC’s unofficial anthem, and it’s been used as a wake-up call to astronauts on NASA missions. Which of those two are you most proud of?

[Laughing] Being a Blues fan, it’s got to be Birmingham. I’m just kidding. Obviously the idea that it’s been used to wake up spacemen is amazing, just the fact that someone sent my tune up there.

Does the idea of that kind of extensive reach blow your mind sometimes?

It makes me feel good about the music I’ve made. I didn’t ever get a proper job, I just carried on doing this. My mum hated me doing music. She’d go: “You don’t want to do that all rubbish. There’s a job going at ATV for a cameraman.” I’d already had about three hits by that point!

Presumably your mum changed her mind after a while.

Yeah – when I bought my parents a house. That’s when she changed a bit, but not that much. She wasn’t that kind about the music, and really disliked my falsetto, when I used to do high screamy ones. It would drive her nuts: “Stop that ’orrible screeching!” That was when I had the studio in the front room.

When you initially wound up ELO in 1986, did you think that was it for good?

Kind of. I just wanted to start producing other people. I started with George [Harrison], then I ended up producing Paul [McCartney] and after that the two Anthology Beatles tracks, which were John’s two singles.

How did you come to produce George Harrison?

George was looking for me to work with him on Cloud Nine [1987]. Dave Edmunds relayed the message to me, and then actually drove me round to George’s house. It was like a giant palace, an amazing place – and kind of scary when you’re going in to meet one of The Beatles for the first time. We went for a row around the tunnels underneath the gardens, these lovely little canals that you could paddle down, then we went into the studio and George played me some of the stuff he was working on.

He said: “Before we start, do you fancy going on holiday? How about Australia?” This was in late 1986. We got to be good pals on that trip. I think he just wanted to know that we were going to get along. He’d had enough animosity in the past. When we got back, the whole of England was frozen solid. George and I started to make these tracks, and I co-wrote a few with him [including When We Was Fab]. It was just fabulous fun.

Apart from the music, what was the secret of your relationship with George?

We just got on really well and had the same sense of humour. After a couple of weeks of recording, he turned to me and said: “Y’know what? Me and you should have a group.”

I thought it was a great idea, and asked him who we should have in it. He went: “Bob Dylan”. So I said: “Right, can we have Roy Orbison, then?” George said: “Of course. I love Roy.” All we had to do was ask. And they all wanted to be in it, so suddenly we had the whole Traveling Wilburys.

It sounds like your transition into the Wilburys happened very smoothly.

It was so easy it was unbelievable. Everybody said yes immediately, without even questioning it. Roy was thrilled to bits, and I then got to be pals with him. He’d moved to Malibu, just a few miles up the road from where I lived, and called me one day: “Hi Jeff, it’s Roy. I’m ready to work!” We’d already discussed me working on a few tracks with him [for 1989’s posthumously released Mystery Girl], and the Wilburys came about during that.

In the late eighties and early nineties you also produced Duane Eddy, Brian Wilson, Ringo Starr and another major influence from your formative years, Del Shannon. At that time did it feel like everything was coming full circle?

I just couldn’t believe that these people were now my mates. I’d looked up to people like Roy and Del Shannon, so to suddenly have them as friends, laughing and having a great time with them, was just fantastic. And then to write songs with them. It was more than I could ever imagine.

They were all wonderful, it’s just a shame that they had to go [Orbison died in 1988, Shannon in 1990]. But I’ve got so many photos of us together, and the film footage of them with me, so it’s always nice to look back now and then, just to remind myself of what a lucky bugger I’ve been.

Was it inevitable that the remaining three Beatles would turn to you when they needed someone to co-produce the first two volumes of the Anthology series in the mid-nineties?

I’m not sure. Obviously George, Paul and Ringo were the ones who had to make their minds up. Because George and I had already worked together, I think Paul was a bit wary of me. He might have thought that I’d be in George’s camp and that I would favour whatever he said. But it was never going to be like that. They’re all Beatles to me, and I wanted to do my best to make it a record that they were all pleased with.

I was staying in a cottage in Paul’s grounds during the recording of Free As A Bird and Real Love, with George in another part of the house. Every morning he’d shout up: “C’mon, ya lazy bugger! Your porridge is ready!” Then it was off to work on the new Beatles record. It was surreal.

John Lennon once said that had The Beatles carried on, they would have sounded like ELO. That must have felt like a huge compliment?

Oh yeah. I was shocked when he said it. I’ve actually got a recording of him saying that. He was a guest DJ on an American radio show in New York, and he said: “Nice little group, these. I love this group.” He got talking about Showdown, and said: “I thought this would be Number One, but [label] United Artists never got their fingers out.” It was fantastic.

What prompted you to revive ELO in the early noughties?

I suppose I was thinking along the lines of: “I’ve done it all now. Where can I go from here? I’ve been in the Wilburys and I’ve produced The Beatles. I might as well do bleedin’ ELO again.”

Would you say you’re a perfectionist at heart? In 2012 you re-recorded the old ELO hits at home, because you didn’t think the originals were quite good enough.

I am really a perfectionist, but maybe not a very good one [laughs]. It’s never as perfect as I would imagine. I try to be one, but I can never quite get it right.

So you’re never satisfied with your finished product?

Maybe. With some of the songs it might just be one little tiny thing – maybe the strings could’ve been a bit louder or maybe the snare’s too loud, whatever. There’s always a bit of that on every record I’ve ever made, except for the new one. There’s nothing on there that I’ve heard – yet – that’s made me wince.

Looking back at it all, is there something you’re most proud of?

I think I’m most proud of the fact that I’m still out there doing it. I haven’t packed it in yet, because I still love it. You can’t ask for more than that.

Jeff Lynne’s ELO’s From Out Of Nowhere is out now. The band tour Europe in September and October - dates below. Tickets are on sale now.

Jeff Lynne's ELO: 2020 European Tour

Sep 19: Oslo Telenor Arena, Norway

Sep 21: Stockholm, Ericsson Globe Arena, Sweden

Sep 23: Herning Jyske Bank Boxen, Denmark

Sep 26: Hamburg Barclaycard Arena, Germany

Sep 27: Berlin Mercedes-Benz Arena, Germany

Sep 30: Munich Olympiahalle, Germany

Oct 02: Amsterdam Ziggo Drome, Netherlands

Oct 05: London The O2, UK

Oct 06: London The O2, UK

Oct 11: Birmingham Arena, UK

Oct 16: Manchester Arena, UK

Oct 18: Belfast SSE Arena, UK

Oct 19: Dublin 3Arena, Ireland

Oct 21: Glasgow The SSE Hydro, UK

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.