“Sex, drugs, rock’n’roll, freedom, art, literature, poetry, Haight Street – it was just Heaven on Earth.”

Jefferson Airplane guitarist Paul Kantner’s description of San Francisco in the mid-60s is also what Jefferson Airplane represented musically. They were the sound of the city’s psychedelic experience and, more specifically, the soundtrack to 1967’s Summer Of Love, courtesy of two major hits: the acid-fuelled White Rabbit and Somebody To Love, a timeless hymn for hippies everywhere – ‘When the truth is found to be lies/And all the joy within you dies/Don’t you want somebody to love?’.

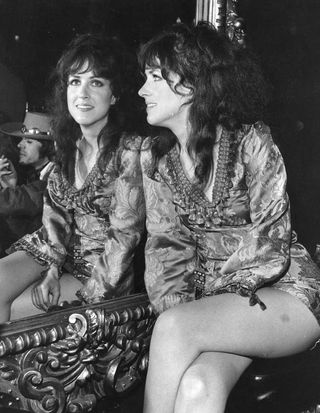

It wasn’t just the chemicals inside the band members. It was also the chemistry between them, epitomised by the contrasting dynamics of the two singers: the exquisite, yearning vocals of Marty Balin, and the imperious, strident tones of Grace Slick. “We had this wild, intense chemistry between us,” Balin says. “Most people thought we were married or having this great affair. But it was just on stage.”

Slick confirms this in her own inimitable style. “Marty was remote off stage. He was just not real chummy. He was the only one in the band I didn’t screw.”

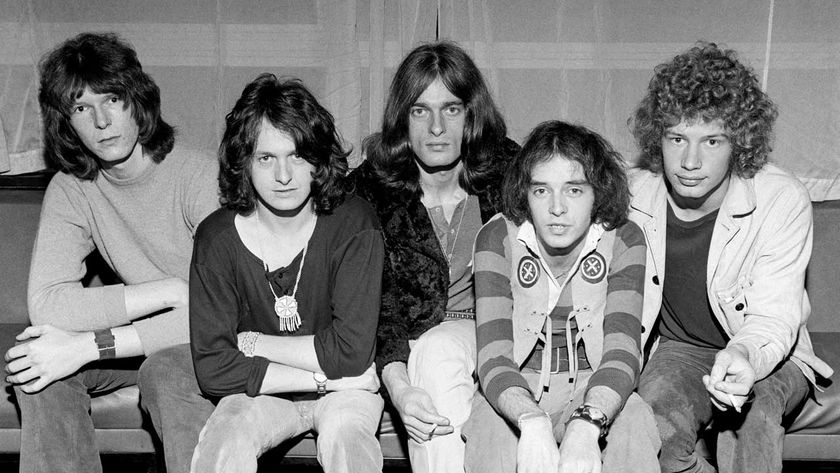

Balin was the one who guided Jefferson Airplane to the runway – albeit prior to Slick. He had released a couple of unsuccessful pop singles in the early 60s and been in a local folk band called the Town Criers. When he heard The Byrds’ Mr Tambourine Man he started envisaging a band that would be a cross between amplified folk and The Beatles.

There was a certain blind intuition involved in putting the band together. Balin had never heard Kantner play, but when he saw this long-haired guy carrying a 12-string and a banjo he walked straight up to him and suggested they form a band. Similarly, when he came across Skip Spence sitting in a club, he decided instantly that he was the band’s drummer. Spence had never played drums, he was a guitarist, but Balin persuaded him to swap his plectrum for a pair of sticks.

They still needed another guitarist. Kantner had his eye on Jorma Kaukonen, who was making a reputation for himself as a solo performer around the clubs. Kaukonen needed more persuasion however. “I was kinda reluctant,” he recalls. “I’d never played in a band before. Plus these guys were not into what I called pure music. Which I know is baloney now, but that’s what I thought at the time. So it wasn’t until I started hanging out with them and that it became apparent something was happening.”

However, Kaukonen was not enamoured with the bass player. And when he discovered that his high-school buddy back in Washington DC, Jack Casady, had started playing bass, he lured him over to California. “When Jorma told me about this group he was joining, I said: ‘You? The purist?’” says Casady, who had just finished his college thesis on child ballads and the folk music tradition. “But he sounded really enthusiastic about it, and I decided to go out and give it a try.”

Balin and Kantner had already decided they needed a female voice, and folk singer Signe Anderson’s rich, powerful tones fitted the bill perfectly. It was Kaukonen who came up with the name Jefferson Airplane. Everybody else laughed when he suggested it, but when everybody else they told laughed as well they decided to go with it.

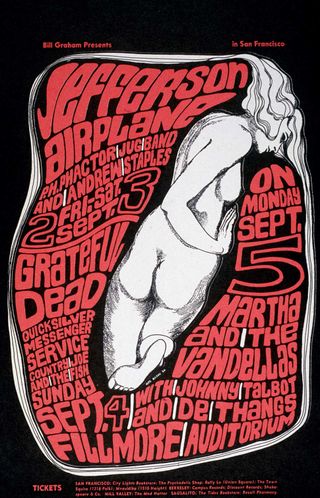

The band made their debut at the Matrix Club, owned by Balin and some of his more entrepreneurial mates, and soon became regular fixtures on the thriving San Francisco live scene which revolved around three of the city’s venerable ballrooms: the Fillmore, the Avalon and the Carousel.

Jefferson Airplane were not the first psychedelic band in San Francisco – Janis Joplin was already making waves in Big Brother & The Holding Company, The Grateful Dead were gradually getting their act together – but they had a musical focus and a sense of purpose that set them apart. And they were the first to land a record contract – with the ultra-straight RCA Records for an advance of $25,000, five times the going rate.

Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, released in September 1966, had a modern folk feel to it, in a jangly, Byrdsy way. It was dominated by Balin’s expansive ballads – he wrote or co-wrote eight of the 11 tracks – and there was little sign of the influence of LSD unless you listened closely.

RCA didn’t until the record came out. But when they heard Running ’Round This World, with its lyric, ‘The nights I’ve spent with you have been fantastic trips’, they got very hot under their starched collars. It was clearly an incitement to sex and/or drugs. The record pressing plant was halted and the was track pulled. RCA then listened to the rest of the album, and demanded alterations to the lyrics of two other songs. But Jefferson Airplane would get their revenge.

Meanwhile, there were more important matters to attend to. One day, they got to a gig to discover that Skip Spence had decided to go to Mexico instead. That wasn’t too serious; his replacement, Spencer Dryden, was a proper drummer. But then Signe Anderson started imposing travel restrictions on the group. Or as Balin puts it: “She got pregnant and she had a crazy husband and didn’t want to move outside the city.”

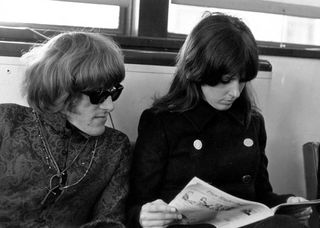

There were only two other girl singers in San Francisco: Janis Joplin and the well-bred Grace Slick who had been working as a model in the couturier department of I Magnin’s department store before forming a band called The Great Society.

“We formed the band after we went to see Airplane one night,” Slick relates, “and I thought: ‘They’re making more than me and they only work two hours a night and they get to drink and smoke dope’. My mother had been a singer, and I thought: ‘I can do that’. My husband had a set of drums at his parents’ house, so it was: ‘You be the drummer’. And his brother Darby had a guitar. But compared to Jack and Jorma we were amateur hour.”

Slick accepted immediately the offer to board the Airplane. In fact The Great Society were disintegrating – along with her marriage. Along with her voice and model deportment, she brought two songs that would enable Jefferson Airplane to take off: Somebody To Love, written by her brother-in-law Darby one night on an acid trip after being dumped by his girlfriend, and her own White Rabbit.

Not that she envisaged her Alice In Wonderland-based fable as a hit. “I wasn’t even thinking of hits. I was just so tired of all the damn love songs. I was just trying to up the possibilities.”

For the record, the dormouse never actually said ‘Feed your head’, did he?

“No, I just made that up.”

Both songs were among the highlights of 1966’s Surrealistic Pillow, Airplane’s second and finest album. It features some of the sweetest songs they ever wrote – Today, My Best Friend, How Do You Feel? – with some of their most ferocious: 3/5ths Of A Mile In 10 Seconds (the $65 that ‘make a poor man holler’ is a comment on the price of a kilo of marijuana) and Plastic Fantastic Lover. Suddenly the whole band were firing, individually and collectively. The Airplane were flying high.

“That was the thing I liked about it,” says Slick. “It was like a smorgasbord. Jorma and Jack were more blues oriented; Paul was 12-string big, grand, Wagnerian cosmic political folk; I’m kind of dark and sarcastic and semi-classical; and Marty was a great love/pop song writer. So you got four for the price of one. And my way of treating stuff is different from Marty’s. And so on.”

About the only common influence was LSD. (There are accounts of the band throwing bagfuls of acid tabs into the audience like M&Ms; LSD was not actually made illegal until late 1966). So it seemed only natural that their next album should be the sound of an acid trip. After Bathing At Baxters has been described by Paul Kantner as “pure LSD among 13 other things”. Nobody can remember what the 13 other things were, but Grace Slick has a memory of “Jack recording a bass part in this huge, gorgeous acoustic room at RCA’s Hollywood studios, and Jorma riding into the studio on his motorbike. Meanwhile there are six guys in the corner sucking on a nitrous oxide cylinder. That’s After Bathing At Baxters.”

Given unlimited studio time by a record company who thought they were going to get Son Of Surrealistic Pillow, the band took full advantage, demanding to produce themselves. Kaukonen and and Casady regard it as their breakthrough album. “We started to learn how to do a lot of stuff with electric guitars – feedback and stuff,” Kaukonen says. “Nowadays every kid learns this as part of their basic guitar vocabulary. But back then it was all different and new. I remember the first time my guitar fed back with a sustained note it was, ‘Wow, really cool’.”

The 12-second guitar wail that opens the album is a defiant portent of the band’s wilful determination to boldly go where no commercially successful band had dared to go before. Unfortunately, amid the jamboree of distorted bass, spacey jams and incomprehensible lyrics no one remembered to bring along any melodies. Marty Balin, who should have provided a few, decided to sit this record out, complaining that he was unable to communicate with the others who were “too stoned out”.

He was also miffed at the growing media perception of the band as Grace Slick & The Jefferson Airplane. Watching footage of the band with the camera zeroing in on Slick while Balin is singing, you can see his point. To be fair, Slick never claimed to be any kind of band leader, but she said what she thought. She thought Balin was “mysterious. He would occasionally just not be there.”

Even when Balin was there he could be upstaged by Slick at any moment. Like the time she blacked up for an appearance on the Smothers Brothers’ TV show without telling anyone: “They sent me to make-up, and there was every colour known to man on this tray. Including black. And I had this white outfit on, and I thought, ‘Aoow yeah!’. But the thing was, because of my features I didn’t look black. I looked like some Indian woman. The band just looked at me and went: ‘Oh God.’”

To the relief of the record company, the next album was mellower than its acid-fried predecessor. Relatively. Balin was back on board. Kantner’s writing was taking on a more strident quality, particularly on the album’s stirring title track, Crown Of Creation. Slick was having fun at the expense of drummer Spencer Dryden who’d just turned 30 (“He was the most child-like of all of us”), as well as the male psyche on Greasy Heart – ‘Girls, wonder why he wants some more when he’s just had some?’. By now it was 1968 and Jefferson Airplane were rolling with the punches.

Politically they upped their profile by playing a charity show for Robert Kennedy, a few months before his assassination. They also raised their avant-garde profile by playing a rooftop concert in New York (a year before the Beatles did the same thing in London) which was filmed by Jean Luc Godard and D.A. Pennebaker, and Balin managed to get himself arrested by the cops when they came to break it up.

The Airplane had several run-ins with the law – not surprisingly, as the authorities correctly believed them to be to the left of Chairman Mao. Some of this was self-inflicted – like when Casady gallantly agreed to test-drive a new drug called STP. An hallucinogenic first synthesised by Alexander Shulgin, STP was stronger than LSD and unfortunately the manufacturers were still have problems figuring the correct dosage. Casady was arrested after being found naked on Santa Cruz Beach, drawing pictures in the sand.

Ohio police seemed have a particular problem with the Airplane, busting them virtually every time they crossed the State line. This could have had something to do with an earlier fracas (caused, as usual, after security started beating up fans and the band started hitting the security) when Kantner spiked the police officers’ drinks while they were laboriously being bailed. Slick can still remember riding back to the hotel and chuckling: “About now they’re gonna be wondering what’s hit them.”

So a European tour with The Doors provided some light relief. As well as two shows at London’s Roundhouse, the Airplane also played the Isle of Wight Festival a year before it turned into a mega-event, and a free gig on Parliament Hill Fields in London.

If Slick was becoming blasé about Airplane’s drug intake, Jim Morrison’s was a revelation: “He basically used himself as a lab rat. He was trying to find out how far you could fuck the human mind up. I remember walking down the street in Amsterdam with him, and kids were running up to us and giving us drugs. I’d politely decline, or take a joint to save for later, but Jim took everything they gave him. That night he came on stage looking like a pinwheel. They had to take him to the hospital afterward he was so fucked up.”

That didn’t stop Slick adding Morrison to her portfolio. She can’t remember which city it was, although she can recall the room décor.

On stage Jefferson Airplane cut the studio crap and spread their wings in a different way, which they caught successfully on the Bless Its Pointed Little Head live album in 1969. Balin remembers that Kaukonen started it: “He just took off one night and it was amazing. The next night he did it again, and this time we all joined in; you’d have this subconscious communication on acid.”

The next studio album, Volunteers, took a more overtly political turn, and Kantner found some grist for his increasingly anthemic songs. The swirling harmonies on the seemingly benign We Can Be Together could not disguise the recurring phrase ‘Up against the wall, motherfuckers’. RCA Records were apoplectic, Airplane were adamant – and, after a three-week stand-off, they prevailed.

Even Balin’s idea for the album’s title track – which came to him when he was woken by the sound of a noisy garbage truck which had ‘Volunteers Of America’ emblazoned down the side – was hijacked by Kantner for a rallying call to the counter culture.

“I have to say that when it got more political it kind of lost certain members of the band,” says Casady, who found solace in a side project with Kaukonen called Hot Tuna, who frequently opened for the Airplane at concerts.

Musically the Airplane were by now getting heavier. “We were being influenced by some of the bands around us,” says Casady. “Cream had come over and opened up all kinds of possibilities. And I became good buddies with Mitch Mitchell of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and ended up playing on a track on the Electric Ladyland album.”

But neither Casady nor Kaukonen was ready to leave Jefferson Airplane yet. In fact We Can Be Together remains one of Kaukonen’s favourite songs.“You’re not gonna believe this but I’ve completely forgotten what the lyrics were about,” he says. “It was the beauty of the music. A lot of the time we’d be playing away and I wouldn’t even hear what Paul was singing.”

Balin, though, had had enough. He quit after Volunteers was released, citing Janis Joplin’s death as the reason. “It was dark times,” he told Airplane biographer Jeff Tamarkin. “Everybody was doing so much drugs. Cocaine was a big deal at that time, and I couldn’t talk with people who had an answer for every goddam thing, rationalising everything that happened. And I thought it made the music tight and constrictive. So after Janis died I thought, I’m not going to go on stage and play that kind of music.” There is a general consensus among the band that Volunteers is the last ‘real’ Jefferson Airplane album.

Spencer Dryden was also feeling the pace and was replaced by young hotshot drummer Joey Covington (Dryden died of lung cancer at the beginning of 2005).

Balin was not replaced as such. Instead the band brought in Papa John Creach, a tall, thin, black, white-haired (what there was of it) 53-year-old jazz and blues fiddle player. “The point was, he was an incredible showman as well as a great musician,” says Casady, who also lured him into Hot Tuna.

Jefferson Airplane released two more studio albums, Bark and Long John Silver, both of which have their moments. Kantner’s polemic was now taking on cosmic dimensions with the epic-sounding Have You Seen The Saucers? and When The Earth Moves Again. In contrast there’s the sublime, in-the-groove Pretty As You Feel that was edited down from a 30-minute jam that included Carlos Santana. “That was just a bunch of us in the studio,” Kaukonen says. “Luckily the tape was rolling, and Joey Covington wrote a song around it.”

And Kaukonen’s best Airplane song – apart from the stunning instrumental vignette Embryonic Journey, on Surrealistic Pillow – is definitely the wistful, restless Third Week In The Chelsea, about the ennui of life of the road. “It’s a nice song, even if I say so myself,” he agrees. “And Grace did a fine job on it too. I guess the pressure was beginning to tell on me by then.”

The Airplane taxied in and ground to a halt in late 1972, although there was the inevitable live album, 30 Seconds Over Winterland, the following year. Slick had decided to sample parenthood with Kantner, and, as she put it at the time: “It’s hard to babysit while you’re hallucinating.”

Casady and Kaukonen decided to devote all their energies to Hot Tuna. “The chemistry that made Jefferson Airplane great was a loose and fragile thing. You can look back on it and think, well maybe we should have done this or that. But we didn’t. I’m still playing with Jorma now – we’ve been together for 46 years – and there’s a great chemistry between us and the rest of the band. But that magical chemistry we had in Jefferson Airplane is very hard to recapture.”

And are they as wild as they used to be? “The only drugs we compare these days,” says Casady, “are cholesterol medications.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock 84, in September 2005