Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson: The Blues Roots Of A Prog Hero

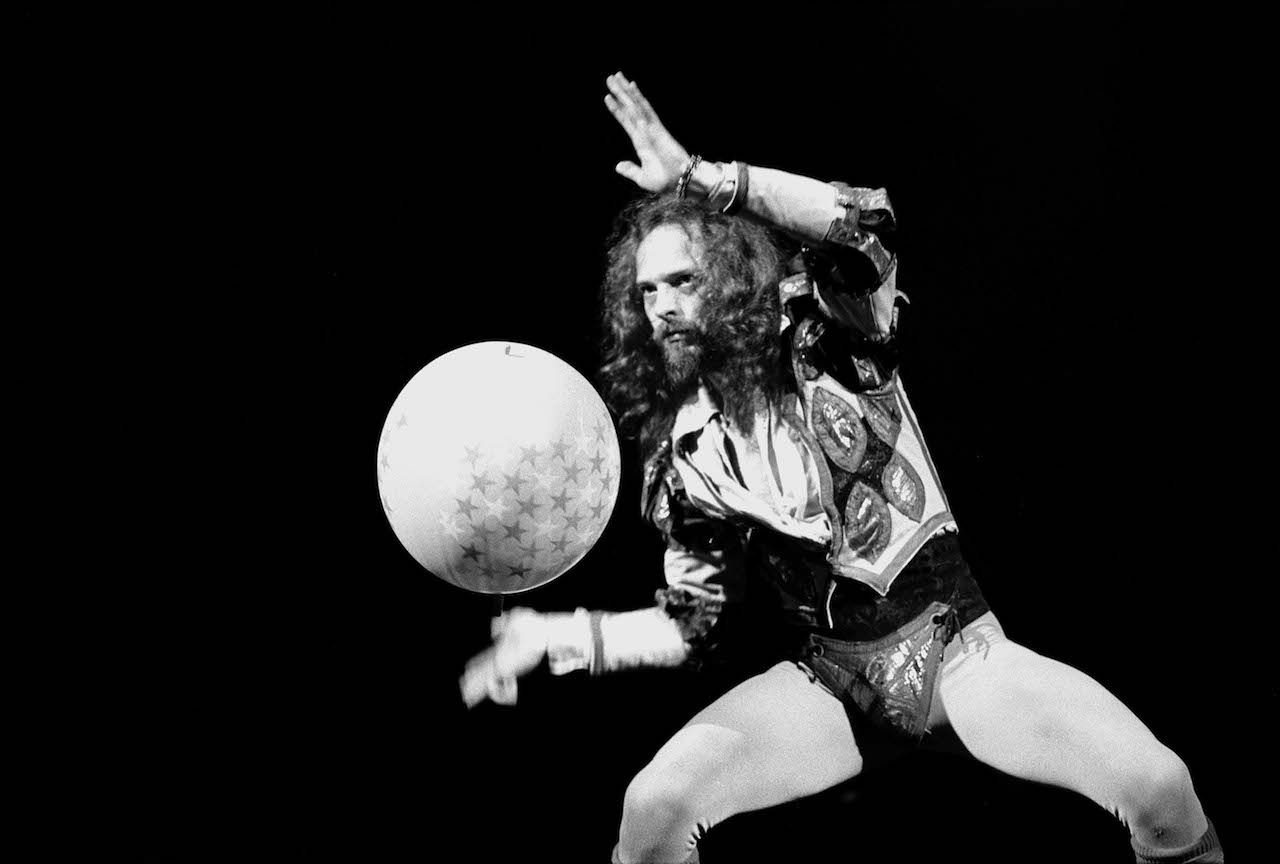

He’s known as the wild-eyed, flute-playing leader of progressive luminaries Jethro Tull. But Ian Anderson started out with rock’n’roll, the blues and the John Evan Band.

This article first appeared in The Blues #10, November 2013.

The pre-Jethro Tull era. According to people in the know, it’s a subject that Ian Anderson has always steadfastly avoided. But having caught up with him at the Progressive Music Awards in September – where he was proclaimed Prog God 2013 – we proposed the idea and a chink in the space-time-prog-blues continuum opened up. So here we are, inside Anderson’s cosy pied-a-terre on a cobbled mews in West London, with October sunshine streaming through the French windows and a brew on the go, made by wife Shona. So far, so good.

Undeterred, Anderson’s father acquired a Spanish guitar with metal strings where nylon was required, “which made the action ridiculously high and almost unplayable”, he laughs, but admits, “I managed to make a bit of a noise on there without knowing any chords,” just as the skiffle movement began to boom. It was perfect timing for kids everywhere with imagination, musical hunger and basic ability. “There were elements of Lonnie, elements of Elvis and the big band jazz that I could tie together,” he explains, “But it was the blues scale that I was playing, the flattened fifth, the minor third.”

In 1959, the Andersons relocated to Blackpool. Aged 12, and with TV programmes like Six-Five Special and Hullabaloo getting live music and blues and folk musicians on British TV for the first time, Anderson lapped up performances from artists such as Muddy Waters, who were finally coming out of $20-a-night US dives to European concert venues and getting recognition. “We were fascinated by what was essentially black American folk music,” he says. “It was raucous and untrained, and quite a lot of it was acoustic music and not electric rock.”

- Motor City Is Burning: How Unrest In Detroit Helped Build Motown

- The Prog Interview – Ian Anderson

- Cuttin' Heads: Sonny Boy Williamson V The Yardbirds

- Ian Anderson – the 10 Records That Changed My Life

Someone was listening to them though: their maths teacher, Paul Jones – affectionately called ‘Granny’. “He was a thoroughly nice man who always had time for all the students,” Anderson remembers of the sole exception at a heavy-handed establishment. “He was the only master who, when he walked into class, everybody would just stop shouting and talking and just listen to him. Granny Jones got through by just being a nice guy, and actually reasoning.”

Granny put himself forward as their guarantor for an unofficial hire purchase agreement with the owner of the music store in Lytham. “You kind of ‘borrowed’ what you wanted. It was like a club guest list. You had your name on a piece of paper there and you went in and ‘borrowed’ an instrument in return for him paying 10 shillings a week. He ended up going nearly bankrupt.”

The group were also funded by John Evans’ mother, a respected piano tutor, who provided a kitchen to rehearse in and a van for transport. A few line-up changes later, under the influence of the Graham Bond Organisation, they added brass, Evans switched from drums to Farfisa, (“a terrible, terrible organ” bemoans Anderson), and 14-year-old drummer Barrie Barlow was recruited after answering an ad in the Blackpool Evening Gazette. By 1965, a newly-christened John Evan Band (a tribute to Evans’ mum for the patronage but dropping the ‘s’ to sound cooler) was ready to take on the club circuit of the North West. But first, that all-important promotional band shot.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“That’s a press shot where the guy next to me has no legs,” Anderson smirks while holding up a picture taken in Studio D in Blackpool, commonly known as the ‘seven heads, 12 legs shot’. The original photo had been taken with six members. Then Johnny Breeze’s guitarist, Chris Riley, came onboard to play rhythm guitar. He was shot in the same studio a little later on his own. “It was the days before Photoshop so he was cut out and pasted in the old-fashioned way.” You can certainly see the join.

Also in the shot are “Barrie, aged about 15, then Jeffrey Hammond, then a one-lunged trumpeter called Jim Doolin who never actually performed with us live, Martin Skyrme who was a saxophonist who went on to play flute as well, and John Evans.” It’s a snapshot of a moment in time where you have five members of a future Jethro Tull, and the flute player from 1973’s A Passion Play. The shape of things to come.

Anderson’s stage persona veered from Elvo – the nickname bestowed on him by his bandmates after a fan had excitedly blurted out how much he sounded like Elvis – and Anderson’s own “distorted idea that I might be a musical version of Patrick McGoohan in Dangerman, a slightly mean and moody kind of thing.” Since moving from Scotland, Anderson felt “my accent was a bit of a mess anyway. So I became the Patrick McGoohan of rhythm and blues.”

At this point Anderson was dropping playing guitar. A big influence on him had been Johnny Breeze’s other guitarist, Frank Blackburn. “While the music was just Top 10 covers, his meticulous and accurate approach was something that impressed me a great deal. But by the time I was beginning to play bluesy solos we were already hearing rumours of these hot-shot players down in London, so I decided I’d be better off playing another instrument.” Anderson traded in his Fender Strat for a flute and a mic and now felt he had “all I needed to change direction.”

More new members resulted in a volatile relationship between Barrie and baritone sax man Tony Wilkinson, sometimes ending in fist fights, often while travelling in the van. “When he was younger, Barrie’s personality was always a problem ’cos he was pushy, outspoken and very critical,” says Anderson. “He’d speak his mind straight away, which wasn’t always the best thing to do!”

If the boys couldn’t make it back home, the sleeping arrangements in the van got tricky, especially since purchasing a Hammond organ. Emergency plans came in to play such as the night they were parked up by Coniston Lake. “We drew straws as to who would have to find somewhere to sleep,”

The next weekend, the boys drew the short straw again. “Two or three of us again had to sleep in a complete pea-soup fog in the middle of the Yorkshire moors,” he laughs. “We pulled up in a little area where we could see some stones and things and a building in the swirling mist. So we huddled up against the edge of this farm building, or whatever it was. Dawn finally broke and we realised we’d been asleep in a graveyard. The next thing, we were running to the van, screaming, ‘Get us out of here!’”

In May 1967, the band appeared on the first show of a tea-time Granada TV talent contest, Firstimers. “We’d been accepted to go on and play a song that I’d written, [Take The Easy Way from the MGM sessions],” Anderson explains. “It wasn’t very good, but it was okay. Most bands were rubbish and very imitative anyway.”

The band’s stagewear that night featured Ian in a black jumpsuit and the rest in matching outfits. “I remember it very well,” he nods. “We’d all gone to get some suits made by Jimmy the Tailor, this gloriously camp chap, so we were all wearing matching hipster trousers and blue shirts, and I, being the frontman, was wearing a satin two-piece outfit with slightly high-rise wrinkly trousers. It was termed the Gene Vincent suit for no good reason other than it was some sort of Elvis-era jumpsuit. An absolutely enormous mistake.”

“Another time I remember Tony being onstage at a dancehall. Tony was a big guy and when he bent over to play bass sax, you’d see what we referred to as ‘builder’s bum’. At one point when he was moving about, bending low, it just went over the edge and his trousers fell down. Brilliant, because right behind him was Jimmy Savile, who was the disc jockey. Jimmy was most amused, of course…”

“Many years later I went to see Eric Clapton at the Royal Albert Hall and, God help me, it’s Andy Fairweather-Low playing guitar with him. I thought, ‘The boy made good,’ and he did it in the most credible of ways, instead of being a wimpy little singer he actually learned to play blues guitar. Hats off.”

More recordings had occurred with Derek Lawrence, this time for CBS and mainly cover versions, with some other recording at Abbey Road a month later, as Don Read guided them into the hands of a new band agency set up by Chris Wright and Terry Ellis. It was clear the band had to get closer to the capital to get more out of the blues scene, and this new partnership. In November that year, they packed up en masse and moved south.

“I left home without a guitar,” Anderson says. “It was about what I could physically carry. So I left with a flute, a harmonica, a tin whistle and a big fat book by Jack Kerouac called Desolation Angels. I had a little suitcase about this big [mimes two-foot in width] and a big overcoat that my dad gave me. I got in the van and went to Luton to seek my fortune as a musician.”

In just a few months, the John Evans Band fizzled under the stress of relocation. But Anderson stayed in a small bedsit, with Cornick moving in with his parents in London. And as they became friends with McGregor’s Engine members Mick Abrahams and Clive Bunker, on guitar and drums, it was a new day…

Meanwhile, back at Anderson towers, the brew’s gone cold and we’ve come to the end of the story. But how did those early days really shape this man?

“The simple basis of improvisation was always seductive and the elements of the blues scale are still present sometimes in my music,” he says. “But I was born the wrong colour, in the wrong country and at the wrong time to have ever been a real bluesman.

“I was happy to leave the spirit of that to those hot-shot professionals, they did it much better!”

Jo is a journalist, podcaster, event host and music industry lecturer who joined Kerrang! in 1999 and then the dark side – Prog – a decade later as Deputy Editor. Jo's had tea with Robert Fripp, touched Ian Anderson's favourite flute (!) and asked Suzi Quatro what one wears under a leather catsuit. Jo is now Associate Editor of Prog, and a regular contributor to Classic Rock. She continues to spread the experimental and psychedelic music-based word amid unsuspecting students at BIMM Institute London and can be occasionally heard polluting the BBC Radio airwaves as a pop and rock pundit. Steven Wilson still owes her £3, which he borrowed to pay for parking before a King Crimson show in Aylesbury.