In 1974 Jethro Tull released War Child, an album Ian Anderson has described as “kind of okay.” It was the result of a failed attempt to make a movie and came while the band were still adjusting after the disasters surrounding the previous year’s A Passion Play. But Anderson regards the year of War Child’s release as containing many more significant events in music. In 2014 he told Prog what 1974 meant to him.

Ian Anderson has an interesting recollection of the music scene in 1974. “It was a time when everything was in the doldrums,” says the Jethro Tull mastermind. “By that, I don’t mean that nothing was happening, but it just appeared that no one knew what would happen next. Anything was possible.”

It was indeed a fascinating one. Monty Python’s Flying Circus ended on TV and Tiswas began. Richard Nixon resigned as US President to end the Watergate scandal, there were two general elections in Britain, and the IRA launched a bombing campaign.

Meanwhile, progressive music was in a state of tumescence, as the biggest names were regularly headlining arenas. “Well, Tull were still playing in theatres, at least in the UK,” recalls Anderson. “In November we did three nights at The Rainbow in London, instead of one night at somewhere like Wembley Arena. It suited us better.”

The London shows opened with a celebrity introduction, thereby accentuating the way prog was becoming accepted as part of the mainstream. “We got Stirling Moss, the racing driver, to do it on all three nights. I’m not sure whose idea it was. But he was one of those high-profile personalities on the after-dinner speaking circuit, and we wanted someone who wasn’t obviously from our world.

“However, even back then he was pretty elderly. The audience reaction was interesting. On the first night, some wag shouted out, ‘Where’s Jackie Stewart?’ [Stewart was one of the pre-eminent Formula One drivers of the early 70s]. I’m not certain how that went down with Stirling Moss.”

Yet it some ways, 1974 was to prove an unrequited time for Tull and Anderson. While they released the successful War Child album in October that year, that hadn’t been the original plan. In fact, War Child began life as a movie project. “There were elements of a potential storyline in our previous album, A Passion Play, and that led to me writing a detailed synopsis for a film. It was about 50 pages long, and done to hopefully enlist the aid of professionals from the movie world.”

He describes the storyline as “epitomising the post-war experiences of growing up in Britain. It was a world I knew, but wanted to examine through different eyes. It was a comedy – but more on the dark side of Monty Python than, say, a Benny Hill knockabout.”

There was certainly interest in the project from some heavyweight names. “Sir Frederick Ashton, who had only just retired as director of the Royal Ballet, agreed to be involved. And the prima ballerina Dame Margot Fonteyn was also kind enough to express an enthusiasm. I also had John Cleese on board from the comedy world, and he said he’d co-write the script with me. The character actors Leonard Rossiter and Donald Pleasance also said yes to being in the cast. The only problem was that both wanted to play God.”

I was politically aware, but disenchanted… You could not like any of the politicians. They were deeply unpleasant people

Things began to go off the rails for this embryonic creation when Anderson had a meeting with his namesake, director Lindsay Anderson. “He tore the whole thing to shreds and was very unkind, harsh and cruel about the film when I met him. I suspect he viewed me as an upstart, entering a world I knew nothing about. It was very upsetting to have someone you admire being so nasty about your work.”

Thankfully, Bryan Forbes was a lot kinder about the film and agreed to direct it. The real troubles came when attempts were made to get American studios to provide the finances. None were prepared to commit money. “Bryan Forbes was very much seen by them as ‘Bryan Who?’ They wanted an American director, and also American actors. At the time, there was just no interest in British cinema so they wanted to relocate the whole story to the States. But it was written in the twilight zone of dark British post-war weirdness – it would never have worked in the States.”

In the end, the process of getting the film off the ground proved too time- consuming for the peripatetic Anderson. “It can take two or three years just to get something agreed in that world, so I abandoned the idea.” He elected to adapt much of the music that had already been composed and demoed for the movie soundtrack to make a cohesive Jethro Tull album instead. To this selection were added songs originally conceived and recorded the previous year in France at Château d’Hérouville, colloquially known to the band as Château d’Isaster.

“We took Skating Away On The Thin Ice Of A New Day, Bungle In The Jungle and Only Solitaire from Château d’Isaster and reworked them for the album. There was a somewhat folksy feel on War Child. Of course, this folk theme was more developed on later albums.”

The 2014 deluxe version offered the chance to hear the original orchestral demos recorded with the movie in mind. “I have to admit that I think these are of dubious value. They were written as movie music, and Tull fans have to appreciate they don’t feature the band much at all. I didn’t play flute or guitar on any of it.

“I think Martin Barre played some classical guitar, and John Evan does some piano parts. Barrie Barlow could have done some percussion. I’m not too sure Jethro Tull fans will want to sit through this stuff. It’s really background music, composed by myself and David Palmer, as he was known back then [now Dee Palmer]. Are they relevant to the album? I don’t know. They’re there for oddity value, really.”

Genesis appeared like a strange one-man band with theatrical elements, because of Peter Gabriel. The rest of them always looked faintly embarrassed

Anderson has even been surprised by some of the material he has unearthed from 1974. “I came across a couple of sophisticated demos I’d forgotten we’d recorded. But then we were in the studio so much at that time. We all lived comparatively close together in Greater London. So popping down to a studio like Morgan in North West London was easy.

“We’d just moved back to London after living abroad for a while, due to the murderous tax regime over here. We’d been advised to leave the country when our first royalty cheque was due and we were facing 83 per cent tax charges. But we never gave up being British residents, as some did.”

Anderson returned to a country that was in a state of flux. The miners’ strike at the start of the year not only led to power cuts, but also the introduction of a three-day working week by the Conservative government, to try to combat the growing energy crisis. This period of instability led to two general elections in ’74, both won by Labour.

“I was politically aware, but disenchanted with all politicians,” Anderson says. “I thought it was okay to shun the whole thing and stand outside of the system. The world was a lot more black and white in 1974 than it is now. The choice facing us was between a very socialist Labour party and an arch and very scary Conservative party. You could not like any of the politicians. They were deeply unpleasant people.”

He believes what happened on the music scene reflected the political and social climates at the time. “You can look back at 1974 and appreciate that it was the birth of punk rock. You had bands like the Ramones starting up, and a lot of this was due to the anger many people felt, the bitterness they had of being marginalised and powerless. That’s why punk came about. Most of the big bands of the time in prog – ourselves, Yes and Genesis – ran in parallel to that world. Punks couldn’t admit to loving us at the time, although a lot did.

“The Ramones were true American rock’n’roll in a grungy, street-credible way. And that sort of music comes round in cycles. In 1969 it had been the MC5, whom Jethro Tull actually played with, and then in 1974 it was the turn of the Ramones.”

It was very competitive. If you felt you were part of a movement then you instinctively felt you didn’t want to be – you had to stand apart

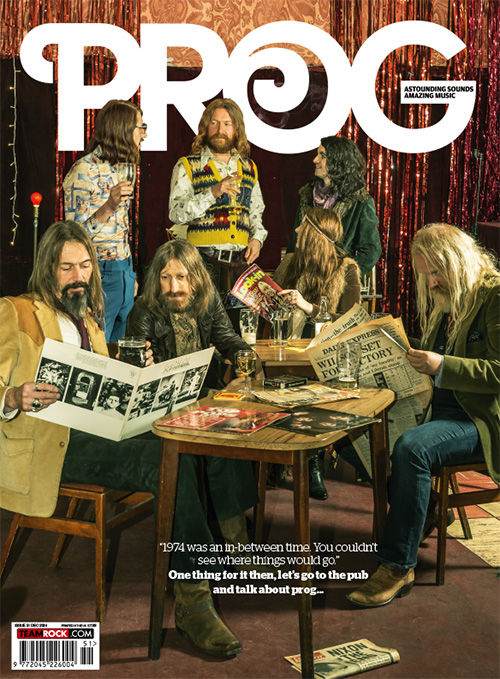

Anderson now believes that the first golden era of progressive music was drawing to its conclusion. “We were at an in-between time. You couldn’t see where things would go. But we in Tull kept our heads down and got on with the next record, the next tour. All of us on the scene at the time were professionals at hiding our heads in the sand.

“With some bands, though, you were never quite sure what to expect. That was true of King Crimson. They changed a lot as they went along. Sometimes these bands floundered commercially, but they didn’t follow the predictable path. They were the brave, restless souls of music. And the ones to whom I warmed.”

“Genesis I never came across, even though we enjoyed the same success at the same time. On The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, they appeared like a strange one-man band with theatrical elements. That was because of Peter Gabriel. The rest of them always looked faintly embarrassed.”

Anderson says of Yes: “I found them noodly and austere and they took themselves terribly seriously. Rick Wakeman did give them a self- deprecating humour when he was in the band, which was their saving grace. But he left in ’74, didn’t he? Still, they were tight, always spot on and had great songs. So you have to admire what they did.

“ELP were not known for humour, but they could take the mickey out of themselves. They eventually realised there was something pompous and silly about it all, although I’m not sure if that all came in retrospect.”

The artist for whom he has a lot of affection, despite his obvious shortcomings, is Captain Beefheart. “We toured together. And I spent a lot of time with him. But he was such a manipulative character that there came a point when being around him was dangerous. He was a paranoid, insecure person, and used to try and intimidate people, but underneath was desperate to be liked. I did manage to keep him at arm’s length, but I would have gotten on a plane at a minute’s notice to go and visit him towards the end of his life. Sadly, I was told he was a recluse by then and would see no one.”

Through mutual desperation, the members of this string quartet paired up with roadies or others in the band

Now, the Tull mastermind can be objective about the way big bands behaved towards each other in 1974, and be honest concerning their relationships. “It was very competitive. If you felt you were part of a movement then you instinctively felt you didn’t want to be – you had to stand apart. But there was also a huge admiration and mutual respect between us all.”

Anderson successfully avoided the brisk hedonism that was a hallmark of the era. Not only has he never had a reputation as a crazed felon of bacchanalia, but there are no hidden stories on this front. “I had no social life whatsoever. I was either on stage, in the studio or else writing music. If I had any time off, I spent it on my own. I loved being alone, just reading; John Le Carré and Ian Fleming were my friends.

“If you spend so much of your life in planes, hotels, on stages, you’re surrounded by people, not to mention an audience every night. You are overwhelmed by the stench of humanity. The antidote was my own company. As a child, I never enjoyed sports at school; I couldn’t interact that way, so I learned to be alone – to read, draw, paint and learn things. People did think I was standoffish, arrogant, a loner.

“But I wasn’t in the mood to go to a roadies’ party, hang out with groupies or indulge in booze and drugs. On the road, I went to my room and read a book. But I did meet my wife, Shona, in 1974, lthough we didn’t get together until the following year.”

For their War Child tour, Tull had an all-female string quartet with them, and that brought its own problems. “Through what I can only describe as mutual desperation, the members of this string quartet paired up with roadies or others in the band.

“And this inevitably diminished their situation musically. As always happens under such circumstances, when these relationships floundered, it brought about its own difficulties, because these personal problems were carried onstage and led to a strained atmosphere.

The upheavals of the social and political spheres meant there was an equal uncertainty in music. It’s at times like these you get innovation

“Any band is obviously made up of different characters. While I was very relaxed being on my own and avoiding all the pitfalls of partying too hard, there were other members of Tull who were extremely gregarious and very needy.

“They embraced the rock’n’roll lifestyle which was prevalent in ’74. But there was also someone like Martin Barre, who had a similar attitude to mine. We could work together and then go our separate ways without needing to live in each other’s pocket.”

Apart from the start of what would become punk, Anderson has no doubt about what, in his opinion, was the most important musical movement of 1974. “It was the birth of glam rock, and with it the seeds were sown for the domination of British music right into the 80s.

“Of course, you had bands like Slade on Top Of The Pops, with their platform soles. But it was Roxy Music whom I really enjoyed. There was a sleazy slickness to the music that appealed to me. The presentation was glamorous and old fashioned, which I liked.

“The arrival of glam rock came at a time when, thanks to progressive music, British artists were commanding global attention. But if anything, it heralded a new era where home-grown talent led the way to an even greater extent. In that respect, it was a year when the musical world was indeed a melting pot. The likes of Cream, The Beatles and Hendrix had gone, and I believe the upheavals of the social and political spheres meant that there was an equal uncertainty in music.

“It’s at times like these that you get innovation. While I don’t feel the big prog names were still necessarily being bold and adventurous, nonetheless that spirit was alive and spreading.”