“Jim’s whole shaman thing only became apparent later, after people wrote books about us. To us, he was just the frontman”: Jim Morrison – the man behind the myth, by the people who knew him

Shaman? Lizard King? Visionary? This was the real Jim Morrison, according to his Doors bandmates

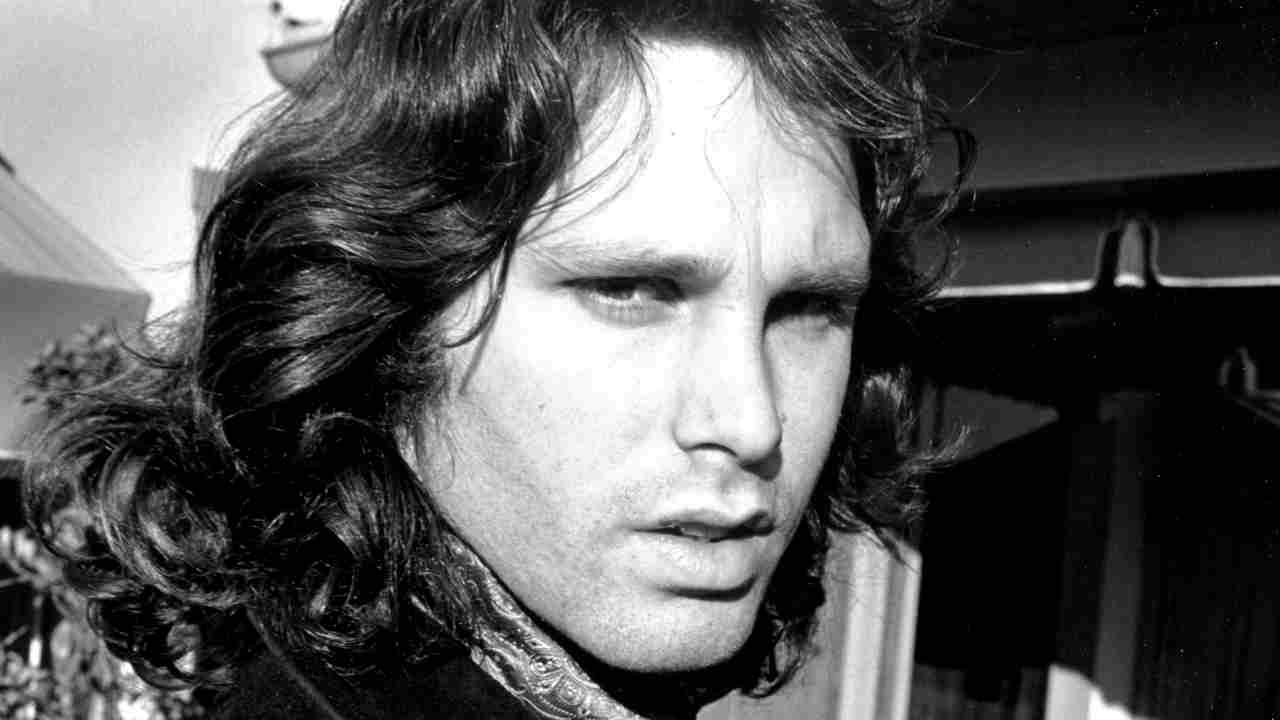

Few rock stars have had the power, presence or charisma to match that of The Doors’ frontman Jim Morrison. From Patti Smith and Joy Division to The Cult, Jane’s Addiction and Stone Temple Pilots, the late singer and his bandmates have inspired countless artists who followed.

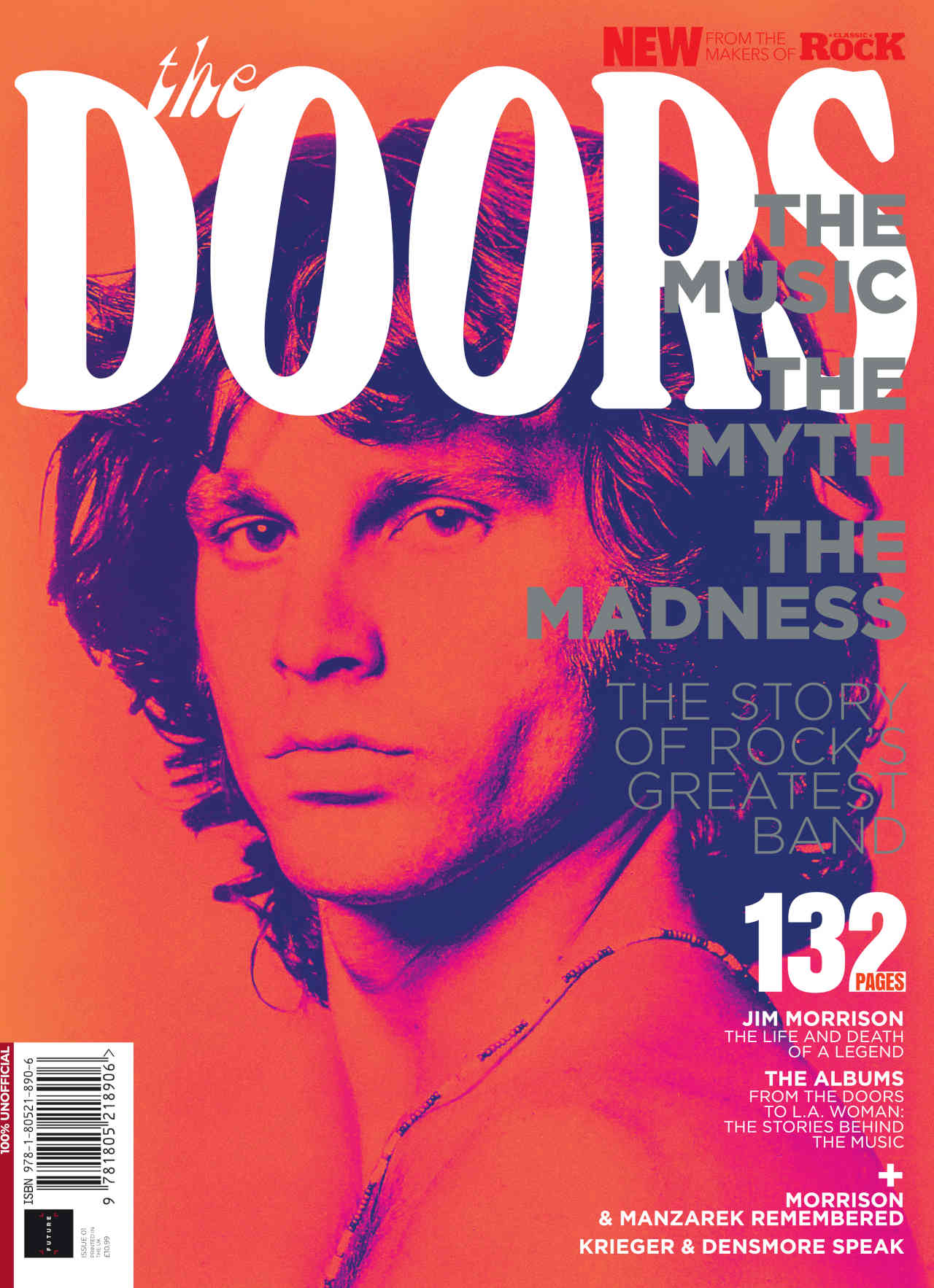

That legacy is celebrated in Classic Rock: The Story The Doors, a special 132-page magazine dedicated to this most influential of bands. Drawing from the Classic Rock archives, it charts the story of The Doors from the clubs of LA to superstardom in the late 60s and early 70s, taking in key points along the way, including in-depth looks at the making of the six studio albums they released before Morrison’s untimely death in 1971 at the age of 27.

In this retrospective feature, originally published in 2007, the singer’s former Doors bandmates – including late keyboard player Ray Manzarek – go behind the myth of the man known as The Lizard King to uncover the real Jim Morrison.

Jim Morrison’s star burned brightly but faded fast. In the space of just three-and-a-half years, his band The Doors released six studio albums plus the searing in-concert recording Absolutely Live. It was a quickfire period of dazzling musical creativity that has never been bettered. From their self-titled debut in January 1967 to their 1971 swansong, L.A. Woman, The Doors’ dark powers scarcely wavered.

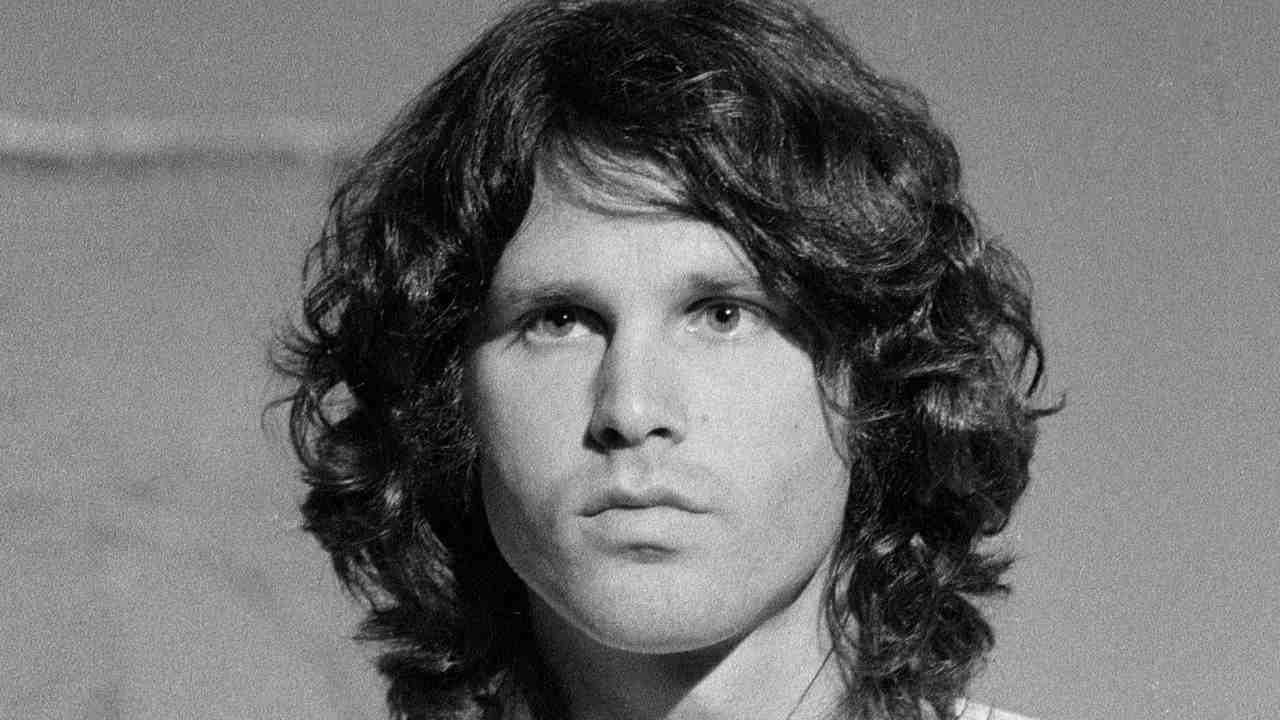

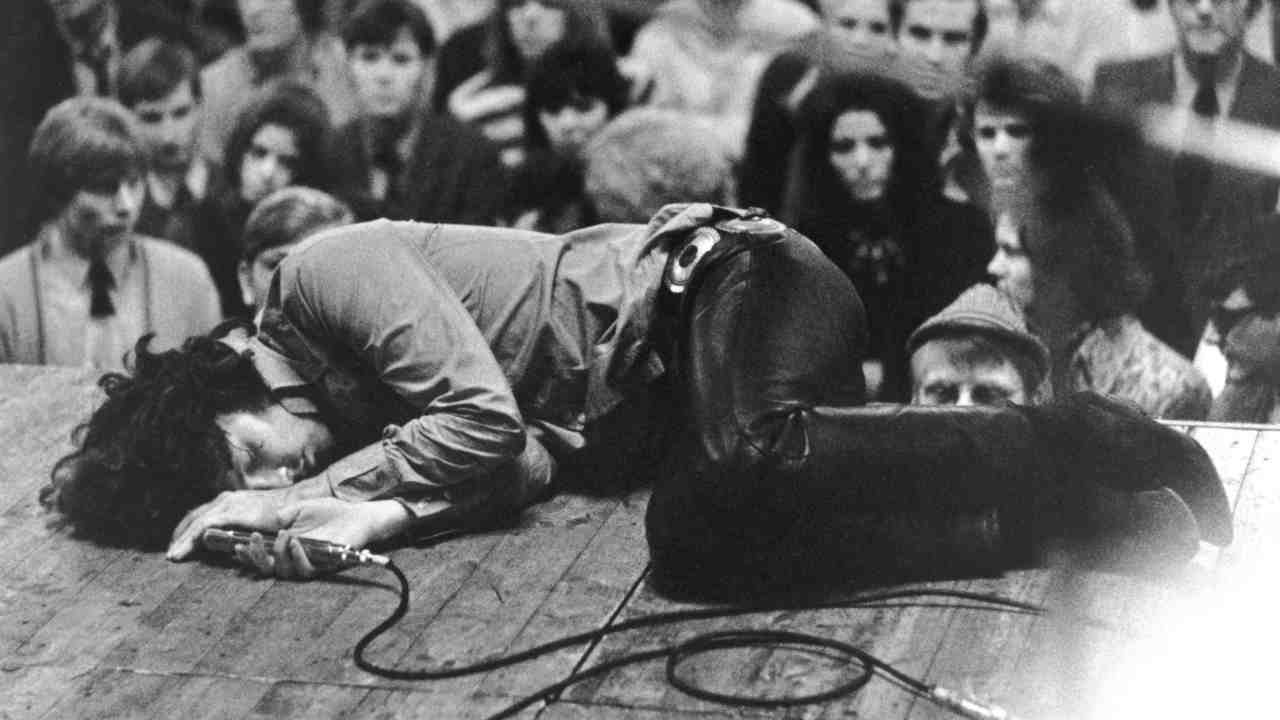

During this tantalisingly brief time Morrison, the Los Angeles band’s talismanic leader, metamorphosed from a sultry, bare-chested Adonis – a prophet, a seer, a sage for the modern rock’n’roll age – into a shambling, bloated drunk. His deterioration was rapid and worrisome. The slinky Lizard King turned into a drawling king snake. Mr Mojo Risin became Mr Mojo Riesling, his miraculous poems reduced to hazy slurs on a parched tongue.

Whether it’s in former Doors confidante Danny Sugerman’s compelling book No One Here Gets Out Alive or in Oliver Stone’s controversial The Doors movie, or any amount of cash-ins and trash-ins in-between, Morrison’s desperate decline has been analysed and dissected to pieces. Arrests, indecent exposure, sexual harassment, police harassment, fuck mother, kill father… you name it, the coals have been raked over so often they’ve turned into brittle dust. And in the middle of it all, on the Moonlight Drive to hell and back, The Doors’ sorcerous music has frequently taken a back seat.

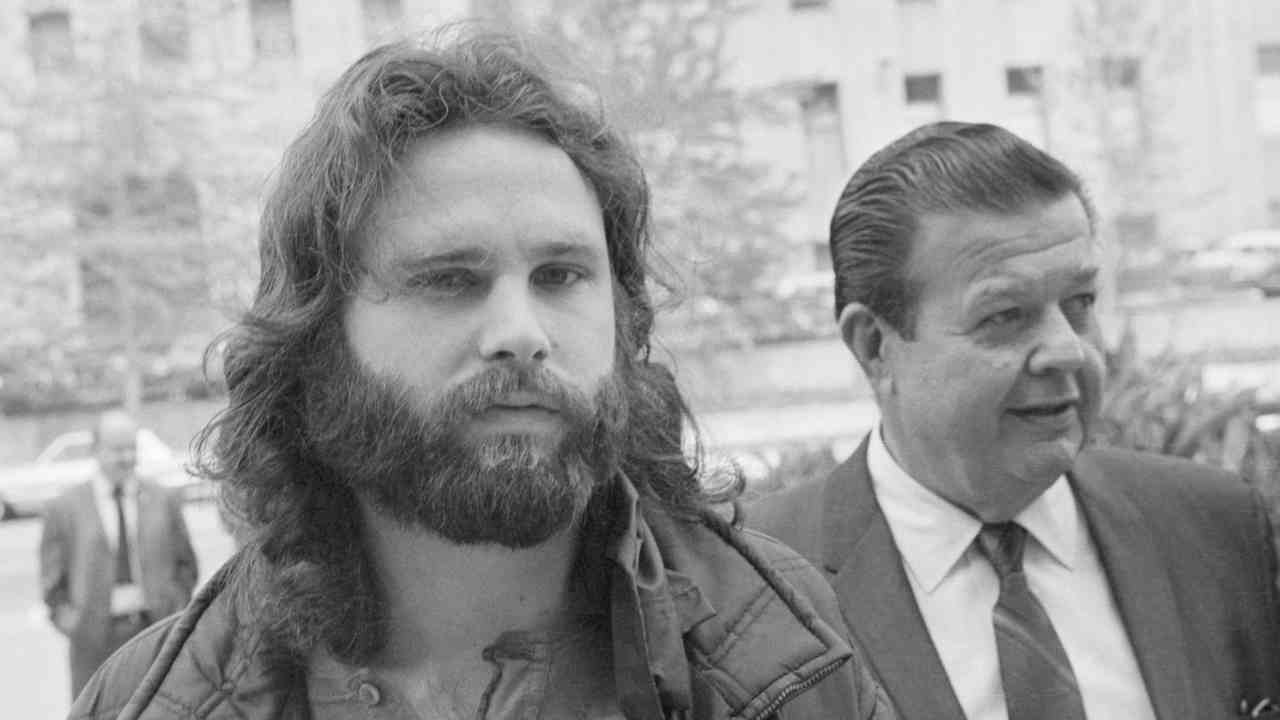

In Morrison’s final days he zipped up his trademark leather strides – just – grew a big buffalo beard and spent plenty of time slumped in the chair of a recording studio. Then he took the first – and last – plane to Paris. You didn’t live much faster or die much younger than Jimbo.

Amazingly, 2007 marked the 40th anniversary of the release of the first Doors album. Certainly to Ray Manzarek, The Doors’ keyboard player, everything still seems like yesterday. “Your mind can take you right back there,” he say, sitting brisk and businesslike on a white leather sofa in a trendy central London hotel. Manzarek is 69 years old now but he looks in his mid-50s. This ain’t no confused psychedelic grandad. He’s as sharp as tacks and his mind is as clear as a crystal ship.

“Now that I’m talking about the 40th anniversary,” Manzarek continues, “I’m back there in 1967, ’68, ’69, the 70s, ’til Jim passed on. When you step back and think about it, it’s like: ‘Boy! That was a long time ago, wasn’t it? Forty years!’ Certainly a long period of time. But hey, that’s the trick of the human brain.”

It’s been an intriguing exercise, piecing together fragments of memory from not only Manzarek but also Doors guitarist Robby Krieger, drummer John Densmore and the band’s engineer/producer Bruce Botnick during a series of interviews. Without exception, the four talk about the strange days of the long-distant past with a mix of wistfulness and affection. There’s only a hint of bitterness at the way Jim Morrison manhandled his demise. There’s precious little ruefulness and a lot of respect. But there’s also a hint of empty longing, a feeling of what might have been.

“To us, he was just Jim because we saw him every day,” says Robby Krieger, as small as Manzarek is tall, sitting hunched on that same sofa 24 hours earlier. “But he definitely had an effect on people. If you didn’t know him, he could really get to you. He was the most influential figure in my life. He could make you believe he was your best friend after five minutes of talking to him.

“But, you know, I wasn’t overly impressed when I first met Jim,” he admits. “He came over to my house, I played some slide guitar for him and he just seemed like a normal guy. It wasn’t until we had our first rehearsal a couple of days later that we got a glimpse of his other side.

“After the rehearsal a guy came back to our house and… I think it was some dope deal gone bad. Jim jumped on this guy and practically killed him. I said: ‘This is our lead singer? Jesus Christ!’”

“What were my first impressions of Jim?” wonders John Densmore down a murky transatlantic phone line. “He was shy. Incredibly handsome. He was really smart and interesting. I did sense there was something special about him. But as time went on and his self-destruction increased,I retreated from it all. I didn’t approve of it. That’s why I pulled away.”

“Yeah, Jim was quite shy,” confirms Bruce Botnick via another transatlanic link. “And he was very introspective. He always kept his poetry book with him. He was always writing in it. He was very quiet. Jim was always quiet.”

So far, so surprising. This isn’t the Morrison of legend, the penis-flourishing, beer-gutted, shit-faced shaman of rock’s scandal sheets. This is someone different. Someone human.

We ask Krieger: what was the craziest thing you ever saw Morrison do? And for a while, we’re right back there in the house of ill repute.

“Probably the time Jim just walked around a little ledge on top of a building,” says the somewhat taciturn six-stringer. “It was the 9000 Building [9000 Sunset Boulevard] where The Doors office used to be. It was 15 storeys high and there was a ledge about that wide that went all the way round the outside. And Jim bet somebody he could walk right around it… drunk on his arse.” When was this? “Maybe during the third album [Waiting For The Sun] or something like that.”

“In The Doors movie they called the ledge incident ‘Jim’s Death Run’. Which it certainly could’ve been,” Manzarek states plainly.

Botnick, however, offers a different take. “The craziest thing I ever saw Jim do? When he lay down on the floor in the living room of my house and watched a movie.”

Because it was comparatively normal?

“By and large Jim was very, very normal. He only went mad when he was inebriated or chemically enhanced. When he was his unaffected self, it was a different story. When The Doors played live, Jim’d go crazy and swing on ropes in theatres like Tarzan. It was very effective and dramatic, but you have to realise he was out of his mind when he did it.

“Without alcohol, which actually was Jim’s favourite drug, he wouldn’t have done that stuff. In the early days he always performed with his back to the crowd. He was that embarrassed. All singers deal with being on stage differently. Some can handle it real well, some can’t. And to begin with, Jim couldn’t.”

Densmore, a man in the eye of the storm, offers his perspective: “One time in the early days when we were riding around in my car, talking about how to get the band launched, Jim pulled out a quarter and said: ‘Watch this.’ And he popped the coin into his mouth and swallowed it. [Laughs]. That’s not a real crazy thing, just a hint that he could be really out of it. I don’t mean to explode Jim’s myth but there’s another side to him that’s maybe been lost down the years.”

At the beginning of this story we made reference to The Doors’ astonishing burst of genius between 1967 and ’71. Their career was meteoric but, compared to the likes of The Rolling Stones, it was also ephemeral. And, of course, it all came to an untimely end on July 3, 1971, when Pamela Courson found her 27-year-old boyfriend all washed up in a bathtub at No.17 Rue Beautreillis, the pair’s Paris apartment.

But even as Morrison took the longest of long holidays, the Doors bandwagon continued to rumble on. Back in L’America their latest album L.A. Woman was being hailed as a masterpiece of corrosive, psychedelic blues. The critical plaudits were gushing in like the waves on Riders On The Storm. And they’ve barely ebbed to this day.

“Yeah, we released a lot of albums in a short space of time. We just kinda kept going, y’know?” muses Krieger. “But in a way we wanted to do as much as we could, because… [voice trails off]. I remember one day when our producer, Paul Rothchild, sat us down, just the three of us, John, Ray and I, and said: ‘Listen, we’ve got to record as much as we can because Jim might not be around for all that long.’ And I hadn’t really thought about it before. But it was the truth.”

Botnick – who engineered the first five Doors studio albums and then produced their tour de force, L.A. Woman – shared Rothchild’s misgivings about Jim’s health prospects at the time. “Especially during the recording of Waiting For The Sun,” he says. “The Doors were firing on all cylinders, they were super-popular and everyone was Jim’s best friend. People were popping whatever [drugs] they had into Jim’s mouth. He’d just open his mouth and swallow. So he was inebriated most of the time. Stoned most of the time. He was all over the place.”

In Botnick’s sleevenotes to a new 40th anniversary edition of Waiting For The Sun, he writes: ‘It was entertaining, in an “Is he going to live to finish the record?” kind of way.’ He also relates the tale of when a young Alice Cooper, who was hanging out with Frank Zappa And The Mothers Of Invention, met up with The Doors at Sunset Sound Recorders in Los Angeles: ‘Both Jim and Alice were holding on to the upstairs studio’s railing, dangling 20 feet off the floor from the second-floor landing. This was one of the spices that permeated the recording and gave Waiting… some of its special flavour.’

“It was definitely very possible,” Botnick tells us now, “that if someone’s hanging two storeys from a balcony, that they could fall and die. That’s why I made that comment about the possibility of Jim not completing the record.”

“Jim had a great line: ‘In that year we were blessed by a great visitation of energy,’” says Manzarek. “Our visitation of energy lasted from October or so of 1966, when we started recording the first album, to the finish of L.A. Woman. Boy, we were creative. Everyone was just full of youthful energy, full of vitality, full of LSD, full of love for their fellow man… and we wanted to change the world through making our music. There was a whole revolutionary aspect to everything we did.”

Although children of the 1960s, The Doors didn’t so much epitomise as subvert the peace-and-love ideals of the time. They didn’t spend their time shuffling down the streets of Santa Monica in Jesus sandals, wielding anti-war placards. Instead they sat out most of the Summer Of Love of 1967 in a gloomy echo chamber in Sunset Sound Recorders. No wonder the album they were making at the time – their second, Strange Days – turned out so damn eerie and hallucinatory.

“For me, the 60s would be summed up by folk-rock bands with jingly-jangly guitars like The Byrds,” says Manzarek. “What The Doors played was much more existential music. We were beholden to the beatniks and to Aldous Huxley… The Doors Of Perception and all that. Beholden to literature and the cinema. Kurosawa, Fellini, Ingmar Bergman… that’s where we belonged. Instead of being from UCLA [University of California, Los Angeles] we were from Bauhaus. The Doors were timeless. Are timeless. We’re from the 60s but we’re not of the 60s. We transcend that era.

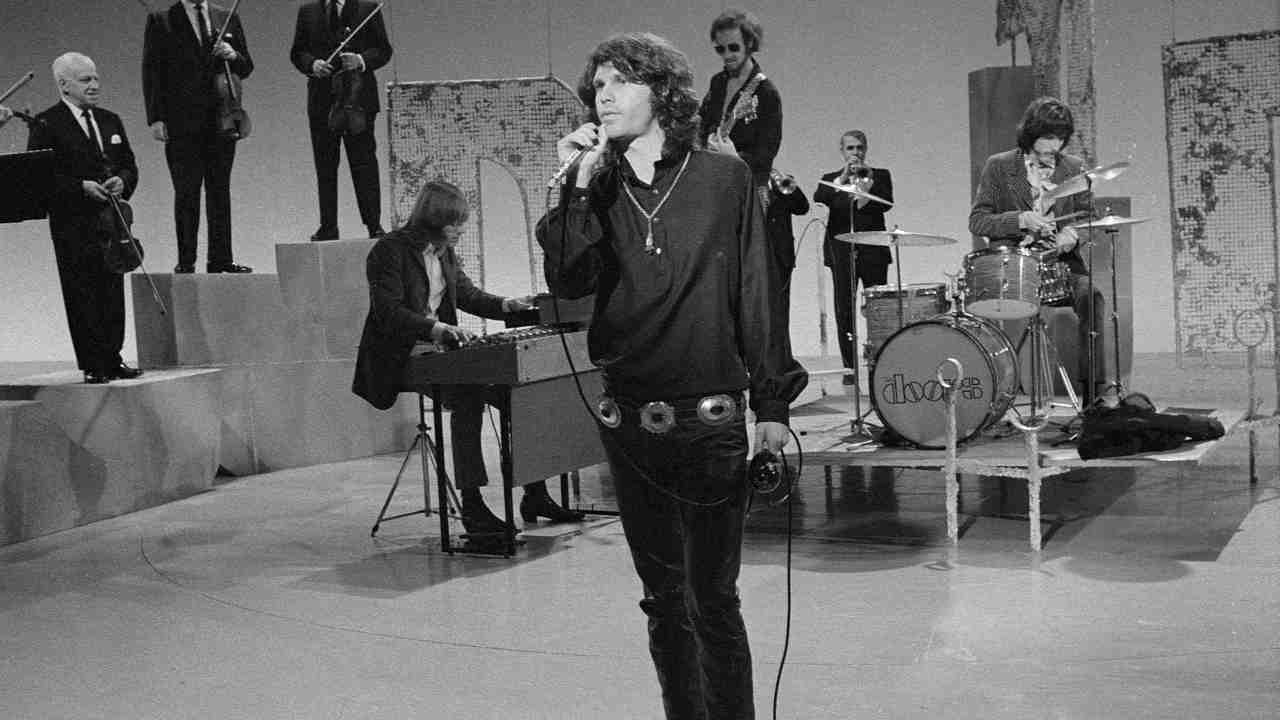

“When we played the Roundhouse in London in 1968 with Jefferson Airplane, that was a perfect example of the difference between Los Angeles and San Francisco. Jefferson Airplane were a great band but they still had those jingly-jangly guitars. The Doors operated in a different space. You can see it on the DVD of the show [The DoorsAre Open]. Jim Morrison… just watch the guy. Holy shit, man. He’s possessed. There’sone point where he gets a look in his eye andthe camera is off to the side. Jim says: ‘We ain’tgot long to go, boss, no, we ain’t got long to go.’ Whoa, chilling! Chilling for me and chilling forthe audience.”

Meanwhile, back in the echo chamber… “We were all meditating, except for Jim,” Botnick recalls. “Jim didn’t meditate so much as brood, I suppose. So we’d go in there, smoke a little bit of cannabis and pay our respects to the maharishi. It felt like a large room, a very large wooden room. It was a nice place to go. We’d have lunch in there. We’d just go in there and sit down on the floor.

“The room had, like, a big refrigerator door. You could shut it and keep people out. In the dark we’d reach out psychically and feel the space. Although it’s been said, ‘If you can remember the 60s, you weren’t there,’ we were there. In the echo chamber.”

Have you ever revisited it?

“I haven’t been in there for at least 10 years. But I know that it’s still here. And I know they have a lock on it to keep people outta there.”

Jim Morrison, it turns out, loved being in the studio environment. For one thing, it stopped him from getting into trouble.

“For Jim, the studio was a safe place, a haven,” says Botnick. “Nobody was after him and he could just be alone with his music. When Jim was in the vocal booth, he never looked into the control room. He never looked at me or Paul [Rothchild]. He never saw us. He just looked straight ahead into the distance. So that was his place.”

“We didn’t go out on the road that much because Jim would get too out of hand,” says Krieger. “So the studio was where we got most of our work done. Jim was usually pretty well behaved when we were recording. But live was where we really killed people.I always thought it was too bad that we never really got to tour like some bands did.”

Manzarek: “The studio was Jim’s laboratory. He was a flamboyant personality on stage in front of the public. But in the studio he was very erudite, very reserved. It was like his poetry was coming to life in his songs. He loved making records because it was such a contrast to the rigours of live performance. So we had both sides. There was definitely a yin and a yang. It was the scientist in the laboratory creating the music, and then this crazed shaman with his electric shamanist band, playing in front of thousands of people.”

Ah, yes… shaman. ‘A witch doctor or priest claiming to communicate with gods, et cetera,’ so the dictionary says. Doors concerts were sometimes compared to shamanic, trance-inducing séances. And Morrison himself believed that the spirit of an American Indian – a shaman – entered his soul when, as a young boy, he witnessed a terrible auto accident. You probably know the tale. A truck had been involved in a collision and had overturned. Its occupants, a group of Native Americans, were lying on the road, bleeding to death.

Morrison recalled the mind-jarring events in the Morrison Hotel song, Peace Frog: ‘Indians scattered on dawn’s highway bleeding/Ghosts crowd the young child’s fragile eggshell mind.’I

“You wanna talk about Jim’s mystique?” asks Krieger somewhat bluntly. “That whole shaman thing only really became apparent later, after people wrote books about us and stuff. To us, Jim was the frontman of the group. Everybody wanted a piece of him, which was fine by us. We weren’t jealous about that or anything. But a shaman? We didn’t really think about that at the time.”

“For me, Jim Morrison was my friend from UCLA and we put a rock’n’roll group together,” Manzarek says. “The iconic Jim Morrison was not the Jim Morrison I knew. The iconic Jim Morrison was the one viewed from the outside.”

Another aspect of Morrison’s persona was ‘Jimbo’. The obnoxious knucklehead he’d turn into when he was raging drunk. The beer drinker and hell raiser.

“I was young…” sighs Manzarek. “I was just too young. I didn’t know about incipient alcoholism.I thought that alcoholics, for the most part, were a bunch of bums on skid row. And there were no detox centres. There wasn’t anything. There was Synanon[a facility on the beach in Venice, Santa Monica, where junkies went to get clean] but I don’t think there were any places where alcoholics could go.”

If there had been such a thing as a Betty Ford Clinic around in the 60s, would Morrison have managed to clean up his act?

“Well, that’s the big question, isn’t it?” ponders Densmore. “There have been artist like Eric Clapton making it cool to be clean and sober, but who knows? We just did not know Jim had a disease called alcoholism, so it’s an interesting speculation.I honestly don’t have an answer.”

“People think Jim drank because he was sick of his rock-star image and wanted to be just a regular guy, but it wasn’t like that,” says Krieger. “He just ate too much, drank too much… and that’s what happened. Jim had no control. The reason he looks so skinny in the early photographs was because he was taking so much acid – and you don’t eat on acid. It wasn’t as though he planned it that way.”

“Jim was just a human being,” says Botnick. “A lot of his supposed mystique is to do with mythology. To be honest with you, we didn’t pay much attention to it at the time.”

“I remember the exact moment when I thought: ‘Jim’s getting out of hand,’” says Densmore. “I wrote about it in my autobiography [Riders On The Storm]. It was when he purchased a lizard-skin suit. I thought: ‘Oh no – he’s buying his own myth!’ He thinks he’s the Lizard King. He thinks he can do anything.”

Manzarek remembers a converstion with Morrison where he said to the singer::“‘You’re drinking too much, you’re killing yourself. Look at you, you’re out of shape. You’re ruining your health, you better stop drinking!’ Jim said: ‘I know, I’m trying.’ And I said: ‘We’re here to help you, man. Anything you need, let us know.’

“But Jim never said: ‘Help me… help me, I’m falling.’ Instead he went back to alcohol. An alcoholic can only stop when he’s ready to stop, or when he’s hit rock bottom, or when he’s become so sick that he knows he’s got to stop. And none of that ever happened to Jim Morrison.

“Jim didn’t hit rock bottom, career-wise,” adds Manzarek. “He was still a great poet, it hadn’t affected his writing, he hadn’t run out of money… he just kept going the way he was. Unfortunately that was what killed him.”

One of the great attractions of The Doors is the coalescence of mysterious poetry and incandescent musicianship – with no full-time bass player required. How much did the surviving three members of the band relate to Morrison the bard? Did they empathise with Jim’s lyrics? Or were his words too personal, or too ambiguous, to get a handle on?

“It was not always easy to figure out what Jim was talking about – and he would never tell you, either,” says Krieger. “I just viewed it as art, mainly. I didn’t want to have to grill him about what the hell he was writing about.”

“You couldn’t ask Jim: ‘What does that word mean? What is that lyric? What is that line about?’ He’d shake his head and go: ‘No, no, n-o-o-o-o,’” says Manzarek. “But that’s the secret of poetry. What it means to you and what it means to someone else may be entirely different. But does it make you think? Does it excite your mind? That’s the point of Jim Morrison’s poetry. But did I know what he was talking about froma Freudian level? Clues as to the depth of Jim Morrison? No.”

“From day one I thought it was wild to have these really poetic words on top of rock’n’roll music,” says Densmore. “I said to Jim: ‘This is unique. This is hot.’ As soon as I heard his lyrics to Break On Through (To The Other Side) [the opening track on debut album The Doors]: ‘You know the day destroys the night/Night divides the day/Tried to run/Tried to hide/Break on throughto the other side’ … I was ready to do it. Those wordsare just so rhythmic, and as a drummer I was raring to go.”

hen, in July 1971, Doors manager Bill Siddons took that fateful transatlantic phone call from Pamela Courson in Paris, neither Robby Krieger nor Ray Manzarek believed Jim Morrison had died.

“People said that kind of stuff about Jim all the time,” says Krieger. “I told Bill to fly to Paris and check it out. He came back and said it was true.”

“I was at home having breakfast,” recalls Manzarek. “Bill phoned and said: ‘I think Jim is dead.’ I said:‘I don’t think so.’ Bill said: ‘No, no, it sounds like it’s real this time.’ And I said: ‘Listen, Jim has died half a dozen times already…’”

John Densmore was more realistic about Morrison’s prospects – or lack of them. “Well…” he considers. “I’d hoped Jim might be an Irish drunk who lived to be 80, but then the reality of it hit home. Because Jim was so tortured, I thought: ‘Well, maybe it’s true, maybe he’s at peace.’”

Bruce Botnick says he knew the truth straight away. “I was in the studio, screwing around with some songs, trying to get some ideas together, hoping Jim was going to come back [from France]. WhenI heard that he’d died, I believed it. Unfortunately,I did. The difference on that occasion was that Jim wasn’t in the country. Every time we’d heard rumours of his death before, he’d been a few blocks away. So you never got the feeling that he was really dead.

“But I knew how many times he’d come close to dying before. He could’ve fallen off the top of a building or taken an overdose. Just gone to sleep and never wakened.”

If you’ve ever made the pilgrimage to Morrison’s grave in the poets’ corner of the famous Père Lachaise cemetery in eastern Paris, chances are that among the mourners – and believe us, to this day there will still be mourners – someone will be whispering: “He’s not really buried there, you know.”

Ray Manzarek takes up the story. “…So Bill Siddons went to Paris and a few days later he called me and said: ‘We buried Jim Morrison in a sealed coffin.’

“I said: ‘Wait a minute – how did he look?’

“Bill said: ‘I don’t know, it was a sealed coffin. It was all in French, I couldn’t read it. But he’s dead. He was in there.’

“I said: ‘You never opened the coffin and took a look at Jim Morrison’s body?’

“Bill said: ‘No, but I know he was in there because Pam [Courson] was crying.’

“I said: ‘That’s got nothing to do with it, man. Pam cries anyway – she’s a hysteric. Are you sure there’s not just a load of bricks and sand in there? I tell you what, people are gonna start to speculate that Jim Morrison staged his own death. And sure enough – here we are, decades later, and we’re talking about the death of Jim Morrison.”

When Manzarek visited the Paris cemetery himself, the keyboardist was reported by onlookers as saying: “Jim’s not there.”

“Well, it didn’t feel like it to me, you know,” he sighs now when reminded of his outburst in Paris. “I don’t know, man. I don’t know. I haven’t heard from him in many, many years, so I assume he’s gone. I don’t see how he could exist without playing music. The most important thing in his life was to sing in front of a rock’n’roll band. That’s where he belonged. So for him not to have been doing that for the past 35 years… I assume he’s gone.”

John Densmore made a separate pilgrimage to the French capital. When he arrived at the cemetery he immediately thought Morrison’s grave looked too short.

“Well, the grave was kinda of small – Jim was six feet or so,” the drummer says. “But I didn’t say that to imply he wasn’t in there. I don’t like those rumours. Ray might still be propagating them. Not me.

“The fact is, Jim was a drunk and he had serious problems. I loved him for his creativity, but it really was tough living with him. But time heals. I accept Jim’s destruction now. He was meant to make a big impact in a short period of time. That was his role.”

“There’s a lot of people who have come and gone like the burst of a supernova,” Botnick says, “and Jim was the best of them. It’s kind of hard to imagine him being alive today and doing all the classic songs. That’s why a lot of old rock’n’rollers have a tough time of it, because no one believes in them any more. I think Jim knew that. He didn’t want to be doing that all his life.”

If Jim Morrison hadn’t died, how long could The Doors have carried on?

“Well,” Krieger replies, “we could have been going today. Or we could have stopped. Who knows? When Jim went to Paris, I fully expected that he would be coming back and we’d be recording again. But he never came back.”

“I hoped we’d last 10 years or whatever,” says Densmore. “I knew we were searchers, y’know, butI don’t want to take it much further than that. What was Jim’s line? ‘We could plan a murder, or start a religion.’ I don’t want to start preaching here – or start a religion [laughs]. As a band, we just worked real hard on making things sound as unique as possible. Then it came to an end.”

“If Jim could’ve stopped his drinking, The Doors would be doing all kinds of exciting things today,” insists Manzarek. “We would’ve slowed down a bit, obviously. But we’d still be active, I’m absolutely sure of it. We’d be making albums, maybe a new record every two or three years, when the songs were ready. We’d be doing movies, touring, all sorts of stuff. Jim writing his books of poetry, y’know… today. Why not? Why the hell not?”

Classic Rock Presents The Doors is on sale now. Order it online and have it delivered straight to your door.

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.