In many ways it’s quintessentially American. We’re into the early hours of the Fourth of July, 1970, and Jimi Hendrix is marking the occasion by striking the opening chords of the national anthem. His distinctive take on The Star-Spangled Banner is unfurled before half a million people in Atlanta, Georgia, while fireworks pop and flash overhead.

He’s nearing the end of his show, having played to the biggest American audience of his life. Appropriately too, it’s been one of his greatest ever performances. He has a terrific new band, a new studio and a bushel of scintillating new songs to boot. The future, from this vantage point, looks to be there for the taking.

There’s a lovely, fleeting moment in Jimi Hendrix Experience: Electric Church – a 2015 film about his show at the second Atlanta International Pop Festival – that encapsulates this sense of celebration. Riffing on guitar in the blackness, Hendrix turns his head and glances up, just as a firework flower bursts red in the sky.

“He was playing to the fireworks,” recalls harmonica player Thom Doucette, also on the bill in The Allman Brothers Band. “It was gorgeous, man. Unbelievable. It was beautiful, it was Jimi.”

Nothing messes with the truth quite like accepted wisdom. The Hendrix myth has it that Woodstock, in August ’69, represented the pinnacle of his live work towards the end of his life. And that his Isle of Wight appearance in August 1970, long since commemorated with a series of audio and visual releases, was his next (and last) festival of any note.

Think again. If anything deserves to stand as a fitting monument to Hendrix’s final months, it’s Atlanta. “By the time Jimi got to Atlanta there was a new confidence building in him,” says his engineer/producer Eddie Kramer. “He was ready to break through to the next stage of what he was aspiring to. Miles Davis and John Coltrane, both senior statesmen of jazz, were respected as grand musicians operating at another level. And Jimi was at that level, there’s no question.”

If The Star-Spangled Banner is the most enduring memory of Hendrix at Woodstock, it can be argued that Atlanta’s rendition was far more meaningful. Woodstock’s untidy scheduling had meant that Hendrix, the last act of the festival, took to the stage at nine o’clock on Monday morning. Most of the crowd had already gone home or were still asleep, leaving him to play to a relatively small 200,000.

Atlanta was something else. Making his entrance at half past midnight, Hendrix played to 500,000 people, the overwhelming majority of whom were all too eager to show their appreciation. The Georgia locale, too, was a world away from upstate New York. Atlanta was still a segregated city with an unrepentant white governor. As such, it was a highly charged environment.

Atlanta also served as a microcosm of civil unrest in America. Only two months had passed since four students were gunned down by the US National Guard at Ohio’s Kent State University during anti-Vietnam War protests. Eleven days later, police killed another two students at a demo against racial discrimination at Jackson State College in Mississippi. Newsweek were swift to declare that President Nixon was in crisis at home as well as abroad.

The dubiously named Honor America Day was set up to counteract the growing sense of national discord. Organised by the Reverend Billy Graham and comedian Bob Hope, and due to take place on the same Fourth of July near the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, it was conceived as a way of uniting the populace. Dissenters were actively discouraged from turning up (“We want to see entertainment that’s on the plus side,” said Hope. “We don’t want anything political.”), while the jingoistic nature of the event was seen by many as little more than an excuse for a pro-war rally. Nearly 700 miles south, meanwhile, the Atlanta Festival was pooling a vast swathe of dissolute American youth.

“1970 was a very interesting time for all people involved, whether it was Jimi, kids in the US or political and civil rights,” offers Electric Church director John McDermott, who’s also an archivist of Experience Hendrix LLC. “You had Kent State, the war in Vietnam at its height and the draft. So that undercurrent was there and these kids wanted to be a part of it. Not everybody everywhere in America was on the same wavelength. And Atlanta was headlined by Jimi, a guy who’d served in the military and who’d faced civil rights oppression. It’s an interesting dynamic.”

Hendrix was a symbol of a new cultural shift, bringing people together through the power of music – what he called his Electric Sky Church. He was also canny enough to resist being drawn into making any direct statements about racial or socio-economic divides. Just prior to taking the stage at Atlanta, Hendrix was asked about the situation by reporters from local underground paper, The Great Speckled Bird. “I’m not thinking about black people or white people,” he replied. “I’m thinking about the obsolete and the new.”

Indeed, 1970 was progressing well for Hendrix. On New Year’s Day he and his new Band Of Gypsys – comprising him, bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles – had played the second of two nights at New York’s Fillmore East. The shows (four in total) were a triumph, assimilating Hendrix’s love of rock and hard blues into a fresh appreciation of funk and R&B. The songs themselves seemed freer and more subjective, exemplified by anti-war jam Machine Gun and Message Of Love, a plea for togetherness in times of turmoil. Issued in March, the album made the top ten both in the UK and US, where it would cling to the charts for over a year.

By April, with Mitch Mitchell in for Miles, the trio had hit the road on the Cry Of Love tour, billed as The Jimi Hendrix Experience. And less than a month prior to Atlanta, Hendrix and the band had begun to lay down tracks at his new recording facility, Electric Lady Studios, in Greenwich Village. A huge amount of money had been invested in the project by Hendrix and his manager Michael Jeffery, but he now had what he’d always craved: a state-of-the-art studio in which he could come and go as he pleased, free to realise the increasingly expansive musical ideas in his head.

“When I came on board the most important thing Jimi wanted to do was reach back to some of the riffs we used to play when we were first learning our instruments,” says Billy Cox, who had first met Hendrix while serving in the US army in 1961. The pair then went on to play as sidemen for various big names on America’s so-called chitlin’ circuit during the early 60s.

“It was a continual process because we were dedicated to the music. We loved coming up with new ideas. There were times when our riffs were so different that we said: ‘Man, if they put that on wax, they would lock us up.’ Because some of them were insane! Songs like In From The Storm, Dolly Dagger and Freedom came about through the usage of a lot of those little riffs. Jimi would say: ‘Man, we’re writing more music than I can write words to!’”

“Jimi had been incredibly focused at Electric Lady,” recalls Kramer. “It was his second home and he was in a good state of mind. When we were in the studio doing Cry Of Love [released posthumously in 1971], which is where a lot of this material ended up, it seemed as if Jimi was searching for something. In a few places he actually found it, but in others it was in development. So it was exciting to witness the development of this new music. He went straight from the studio to play Atlanta, which gave him the chance to perform this stuff.”

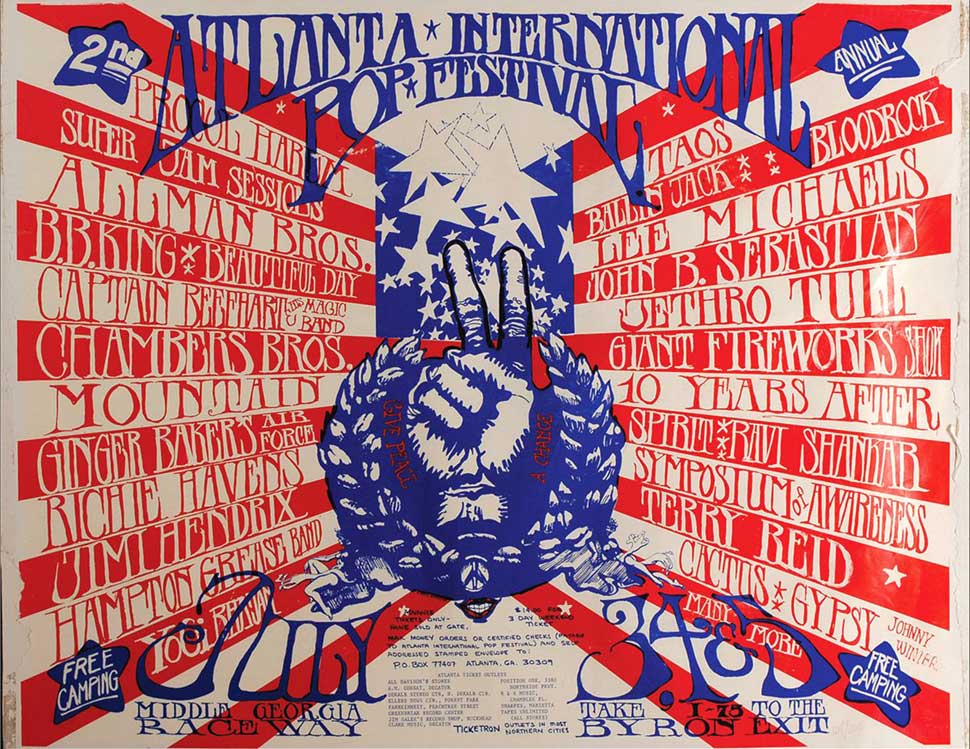

The Festival actually took place in the small enclave of Byron (pop. 1,368), some 100 miles south of Atlanta. Eager to build on the success of the previous year’s gathering, promoter Alex Cooley set out styling the second Atlanta International Pop Festival after Woodstock, promising “three days of peace, love and music”. And, despite the opposition of state governor Lester Maddox, an old-school politician who kept an axe handle in his restaurant to deter those he considered undesirable, the event attracted people from all over the country.

Cooley coerced a local farmer into leasing his field, which sat next to the Middle Georgia Raceway. The arrangement bordered on the farcical. The farmer, remembers Cooley in the documentary, drank Scotch and milk all day, and produced gallons of moonshine from a still underneath the racetrack. The local sheriff had no officers available and presided over a tiny police station that doubled as a makeshift courthouse. There was one helicopter, but no walkie-talkies, rendering communication almost impossible. In order to help with security, the sheriff called in The Galloping Geese, a biker gang from Baton Rouge. There was one road in and one out, and the heat reached 100 degrees.

Into this chaos poured hordes of longhairs and hippies. It was apparent that the town wasn’t equipped to handle the volume of people. Sensibly, the local officials decided to adopt a hands-off approach, monitoring the festival-goers without resorting to strong-arm tactics. People stripped naked in the searing sun, drugs were consumed openly and fire trucks were brought in to hose down the crowd when temperatures became too much.

Cooley, who’d anticipated around 100,000 people, surveyed the scene from a helicopter on the Friday afternoon. Only then did he realise how much he’d underestimated the turnout. “Traffic was backed up 90 miles to Atlanta,” he remembered. “I was scared to death.” Initial plans to charge 14 dollars for a three-day ticket were scrapped when people broke down the surrounding 20 acres of fencing, demanding instead that the festival be free. Maddox flew over the site later in the weekend and declared it a disaster area.

Aside from Hendrix and local heroes the Allmans, others on the bill included BB King, Grand Funk Railroad, Richie Havens, The Chambers Brothers, Mountain, Spirit and Johnny Winter. Hendrix arrived by helicopter at 10 in the evening to discover most of the place in total darkness. The limited capacities of Georgia’s rural power system, it transpired, meant that the generators were unable to provide enough lights.

From the minute he took to the stage two-and-a-half hours later, it was clear that Hendrix and his new iteration of the Experience were enjoying themselves.

“Jimi had played in the South when he was doing the chitlin’ circuit and knew it really well,” observes Kramer. “And I think the audience was incredibly receptive, very laid back. There were no bad vibes. I got the feeling that he was very relaxed and the music speaks for itself. Jimi loved playing outside, particularly at night.”

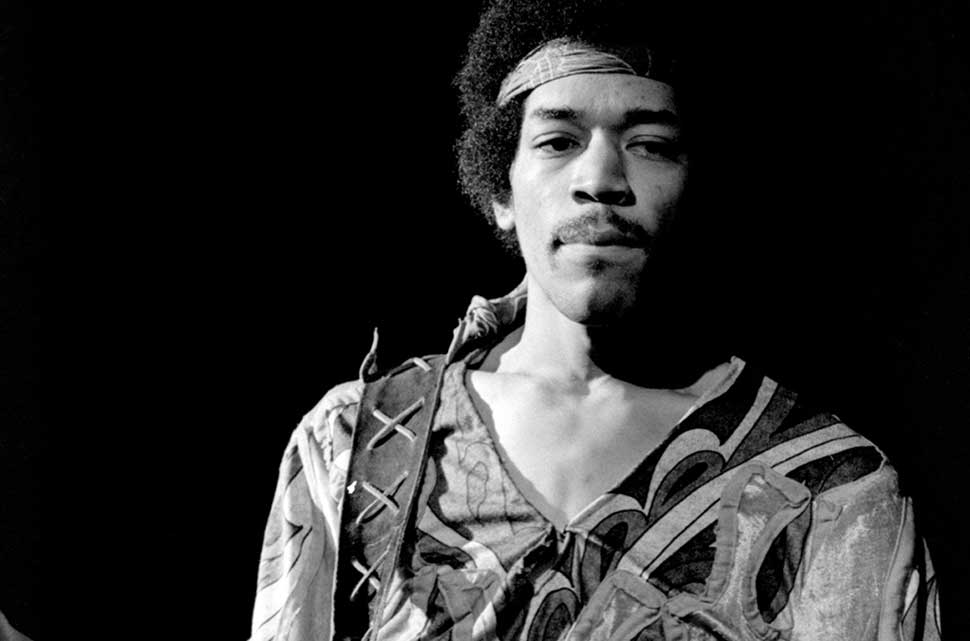

The Experience gave them what they wanted. There’s a riveting version of Spanish Castle Magic three songs in, building to a brilliant flurry of Foxy Lady, Purple Haze and Voodoo Child (Slight Return). The wild-man act of a few years earlier is gone. His old witch hat and military jacket have been replaced by headband and loose, kimono-ish shirt. This is a more serene, focused Hendrix, utterly locked into the surges and suggestions of the music.

“He stands there, almost statuesque, hardly moving,” Kramer says of his stage demeanour. “He wants people to concentrate on him as a musician, as someone who’s playing some serious shit. I think that was in his mind as he moved forward throughout 1970.”

The trio clearly have an extraordinary understanding on stage. This is perhaps best exemplified, oddly enough, by a rare hiccup during the intro to Bob Dylan’s All Along The Watchtower.

“After about two bars Jimi goes, ‘As I was saying…’ and I knew he was going to switch to the right key,” Cox recalls. “It could be just the way he moved his arm, but we knew him and could see what was happening next. Jimi was freer and more confident at that time, because he had his boys with him. Mitch was one of the greatest drummers I’ve ever worked with. Jimi knew that he could go out on a limb as far as he wanted to.”

“That final iteration of the band was one of the best in terms of what they each brought to the table,” adds Kramer. “Billy had his funkiness and R&B roots, while Mitch, interestingly enough, had adopted some of that bluesy R&B stuff from Buddy Miles in the Band Of Gypsys and melded it into this new version of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. In terms of the performance in the movie, I thought the communication was on such a high level. It only needed a little look or nod from Jimi. It was seamless, telepathic.”

The real boon of the Atlanta show is Hendrix’s decision to showcase a handful of songs from his recent Electric Lady sessions. There are limber, captivating versions of Room Full Of Mirrors, Freedom and Straight Ahead (the last two would surface on Cry Of Love; the former was made to wait until 1997 for an official release, on compilation First Rays Of The New Rising Sun). These songs – vivid, funky, pyretic – all suggest that Hendrix was pushing at the frontiers of his own capabilities, ready to break through to a whole new phase in his creative life.

So wrapped up is he in the show that Hendrix completely forgets that the fireworks are scheduled to happen. He finishes a rapturously received Voodoo Child, thanks the audience and begins to stalk off stage, only to be taken aside by one of the stage crew, who whispers into his ear. The cigarette lighters, like thousands of tiny candles, flicker in the crowd as Hendrix comes back on to do Stone Free. Then comes The Star-Spangled Banner. Even after he’s long gone, the punters refuse to stop chanting his name.

Since dubbed the ‘Southern Woodstock’, the second Atlanta International Pop Festival proved to be the last. After weeks of clean-up operations, new state legislature ensured that it could never be repeated in Georgia. It also signalled the beginning of the end for mass music festivals across the US.

“It was a great end to an era,” says the Hampton Grease Band’s Glenn Phillips, reflecting on Hendrix’s performance. “It was a powerful moment.”

One reason why Atlanta 1970 has been less celebrated than Woodstock or The Isle of Wight was its lack of accessibility. Audio bootlegs of Hendrix’s set have been doing the rounds for years, but the visuals have proved far more elusive.

Filmmaker Steve Rash, who went on to direct The Buddy Holly Story and Can’t Buy Me Love, shot footage of the entire festival, but his plans to release a documentary were scuppered when his Hollywood distributors reneged on a deal.

“In those days there were no ancillary markets, it was theatres or nothing else,” Rash explains. “And by the next summer it was old news.”

The film lay in his basement for a decade, then spent the next 20 years in his barn in Pennsylvania. It was only in 2000, after he saw an ad in Popular Science magazine from a company who specialised in restoring old 16mm film, that he began to think it was saveable. A lab in New York eventually salvaged around 80 per cent of the footage Rash shot (4,000 reels of the stuff), after a year’s work.

“It was an absolute miracle,” he said. “As well as the Hendrix material for Electric Church, I also have six hours of people like the Allman Brothers Band, Procol Harum, Grand Funk Railroad, John Sebastian and The Chambers Brothers.”

In the meantime, Rash’s compelling footage of Hendrix is a reminder of an artist whose best work may have still been ahead of him. Two months on from Atlanta, however, he was dead from a drugs overdose.

“Before Jimi died he was talking to Chas [Chandler, ex-manager] again and I truly believe, having seen this Atlanta footage, that he was right there with the concept of where he was going next,” posits Kramer. “He’d reached the crossroads.”

“When you see things like Atlanta it just reminds you of the possibilities,” adds John McDermott. “But in the end we lost a tremendous artist who, 45 years later, still inspires, intrigues and confounds. How many artists have that currency, that power?”

Billy Cox admits that “my whole world just shut down” when Hendrix died. He maintains that, “if Jimi had survived over the next ten years, the music would’ve been something wonderful. He had this concept of the Sky Church and Electric Church and had planned for this full manifestation. I saw his vision. He was global before the rest of the world became global. He was a future man.

"What makes Jimi just as relevant today is that he wrote in the now. Mozart, Handel, Coltrane, Gershwin, Hendrix: these guys all did that. I looked at Jimi as a cosmic messenger and he saw music as his means to bring people together.”

Jimi Hendrix: Electric Church is available to rent on streaming platforms.