No one remembers the exact date of Jimi Hendrix’s first professional gig, because at the time no one, not even Hendrix himself, thought the event was significant enough to keep a record of it. We do know that it was in the autumn of 1959, and that the performance took place in the basement of Temple De Hirsch Sinai, one of Seattle’s biggest synagogues.

In that era, Jimi wasn’t even Jimi. Back then he was known as James to his high school teachers, Jimmy to his family, and Butch to many of his musician friends. “Butch was his nickname for a while,” recalled Sammy Drain, who grew up down the street from Jimi, “because he was so shy. But he wasn’t shy about learning licks from other guys.”

Hendrix had only got his electric guitar the previous year, and at 16, he wasn’t even considered the best guitar player on his street. He’d jammed with the neighbourhood boys in garages and at community centres, but had never done an actual gig before a few older high-school boys asked him if he could play at a dance at Temple De Hirsch Sinai and Jimi had said yes.

Drain didn’t attend that first show, but Jimi’s girlfriend, Carmen Goudy, did. She remembers him being extremely nervous, with none of the confidence that later would mark his storming of London stages in 1966 when he became a star. “Do you really think I’ll have fans?” Jimi nervously asked her before the show. Goudy says he was so nervous she thought he might throw up.

He had a reason to be anxious. Hendrix had only been playing the electric guitar for a bit over a year by then, and despite showing intuition for the instrument, according to his childhood friends, he still wasn’t particularly good. His playing was often untethered, as if he hadn’t come to terms with this unwieldy machine.

His erratic playing was accentuated by the fact that bands only succeeded in that day by playing popular dance numbers, which weren’t Jimi’s forte. Dave Lewis, one of Seattle’s most accomplished bandleaders, once recalled a time when Jimi sat in with his band: “He would play this wild stuff, but the people couldn’t dance to it. They just stared at him.”

Before the synagogue gig, Hendrix paced the hall of the building with his guitar strapped on, as if in his head he was already rehearsing what he planned to do. It would be a huge leap from jamming with neighbourhood boys to playing for an audience that didn’t know him – and one that needed to be entertained. For a kid who grew up in abject poverty, dreaming of music as a career, the idea of a paying gig was also a heady elixir.

Goudy remembers what happened when the show started, and how quickly things went awry. “During the first set, Jimi did his thing,” Goudy recalled. “He did all this wild playing. And when they introduced the band members and the spotlight was on him he became even wilder.”

When the set ended, Goudy went to the back of the building to find Jimi to congratulate him on such an exemplary performance. But he was nowhere to be found. She searched the entire building. Finally she left, and saw him in an alley behind the synagogue. She would recall years later that he looked as if he was moments away from tears. He’d been fired. The bandleader had said he was simply too wild, and that the way he played interfered with the crowd’s dancing.

The synagogue was at 15th and Union, which was only a few shorts blocks north of where Jimi lived at the time, but rather than walk home he simply sat down in the alley, despondent. For over an hour, Goudy recalled, he recounted every aspect of his short appearance on stage, frustrated that what he thought was an extraordinary performance had not been well-received by the audience, or by the bandmates he thought he was joining up with.

Goudy suggested that maybe he play more rhythm guitar, and not make his solos as flashy, or as long, because in an era when vocal pop music reigned, guitarists were considered part of the band, not the main show. Jimi was immoveable, though. “That’s not my style,” he insisted. “I don’t do that.”

His implacability had significant economic implications, because the only way for a guitarist to make a living in Seattle then was to play with a popular dance band. Goudy began to doubt whether hooking up with her clearly talented paramour would ultimately be a smart decision in the long term.

Even in that synagogue gig there was already a sense of ‘otherness’ to Jimi Hendrix, as if he were somehow not of this world. Faced with the opportunity to fit in and make money with popular music the way everyone thought it should be done, he balked. The Temple De Hirsch Sinai gig was in many ways an unmitigated disaster, but in that disaster was also the making of greatness. Jimi was inventing himself, and even if it meant poverty and standing in an alley rather than being on stage, he was cementing what would be his musical signature.

When he became famous seven years later in London – after many stints on the road in the American south with R&B bands, and also striking out in New York City – it was precisely his ‘otherness’ that made him a star. By playing exactly the kind of flashy guitar that had got him fired from a Seattle synagogue basement, Hendrix put every guitar player in London on notice.

Hendrix, as Jeff Beck once described, “reset all the rules”. And it all began in the basement of a Seattle synagogue.

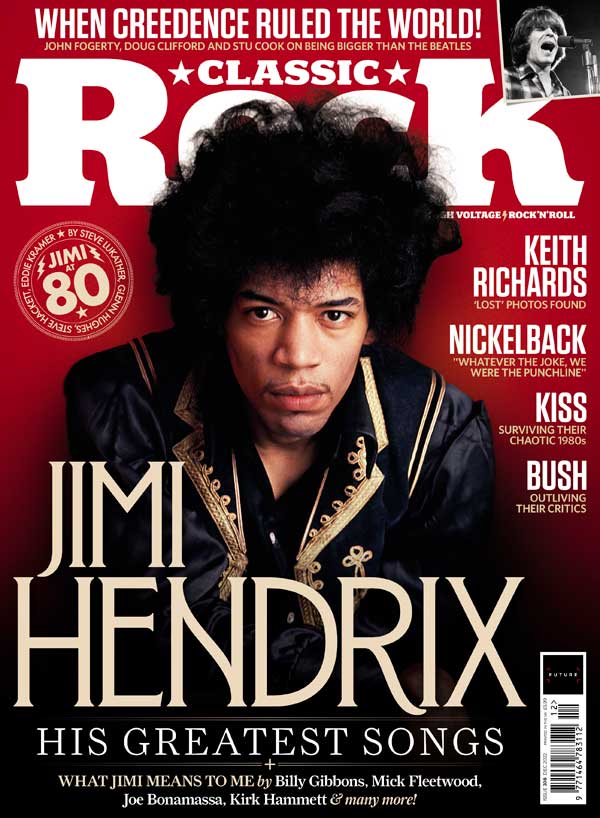

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 217, in December 2015. The new issue of Classic Rock is a celebration of Jimi's songs and influences, and it's on sale now.