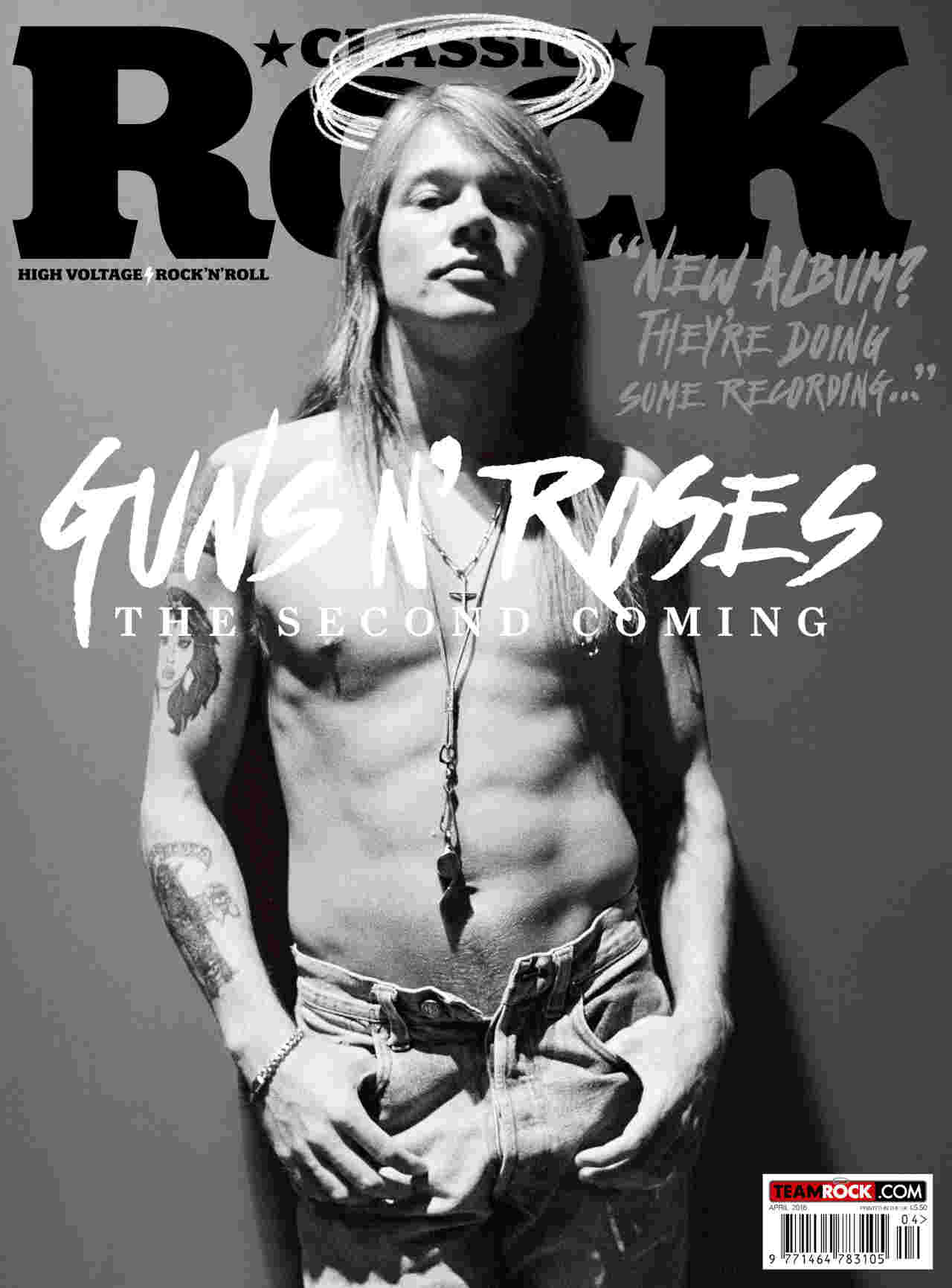

The late Jimmy Bain played with everyone from Rainbow and Dio to Kate Bush and Roy Harper. In 2016, shortly after his death, Classic Rock looked back of the life of a bassist whose playing was matched by his character.

When the MSC Divina set sail from Miami for Def Leppard’s Hysteria On The High Seas Rock Cruise on January 21, no one could have known how ill-fated its five-day journey would turn out to be.

The omens didn’t look good from the start. Leppard were forced to cancel one of the sets they were due to play when Joe Elliott was struck down by laryngitis, leaving bandmates Viv Campbell and Phil Collen to cover for him.

But that wasn’t the worst thing that happened on the ship. On January 23 Jimmy Bain, veteran bassist with Last In Line, was found dead in his cabin by the ship’s staff. No one saw it coming. The 68-year-old Scot had been receiving treatment for pneumonia, but he’d played a pre-sail gig and soundchecked with the band he’d formed with fellow former Dio members Viv Campbell and Vinny Appice. What nobody – including Bain himself – knew was that the bassist was also suffering from lung cancer.

“Jimmy played great and even sang that night while holding a heavy bass guitar,” Appice said in a statement. “Never complaining, never asking for help. He didn’t want to let anyone down.”

Ronnie Dio used to say proudly that he had sung on three of the most influential hard rock albums in history: Rainbow’s Rising, Black Sabbath’s Heaven And Hell and Dio’s debut album, Holy Diver. Jimmy Bain also played on two of them, although the perception of him as a sideman means his contributions have been overlooked.

“Jimmy didn’t crave superstardom,” says Viv Campbell. “ He could be a frontman but was just as comfortable as a supporting player. He was a very creative guy, but the problem was that he’d never follow through. He’d write a gem of a song and then put it away in a box somewhere.”

If Jimmy Bain had been just a great musician and songwriter, that would have been enough. But he was a far more colourful character than that. There was boozing and drugging, arrests and 24-hour parties. He even married into aristocracy in the 80s, tying the knot with the daughter of the Marquis of Bute (it ended in divorce). Like his friend Phil Lynott, he was an unrepentant rogue dedicated to the romance of rock’n’roll.

“I was famous for being lit up, falling over and still being able to play,” he once said. “It almost became part of the show.”

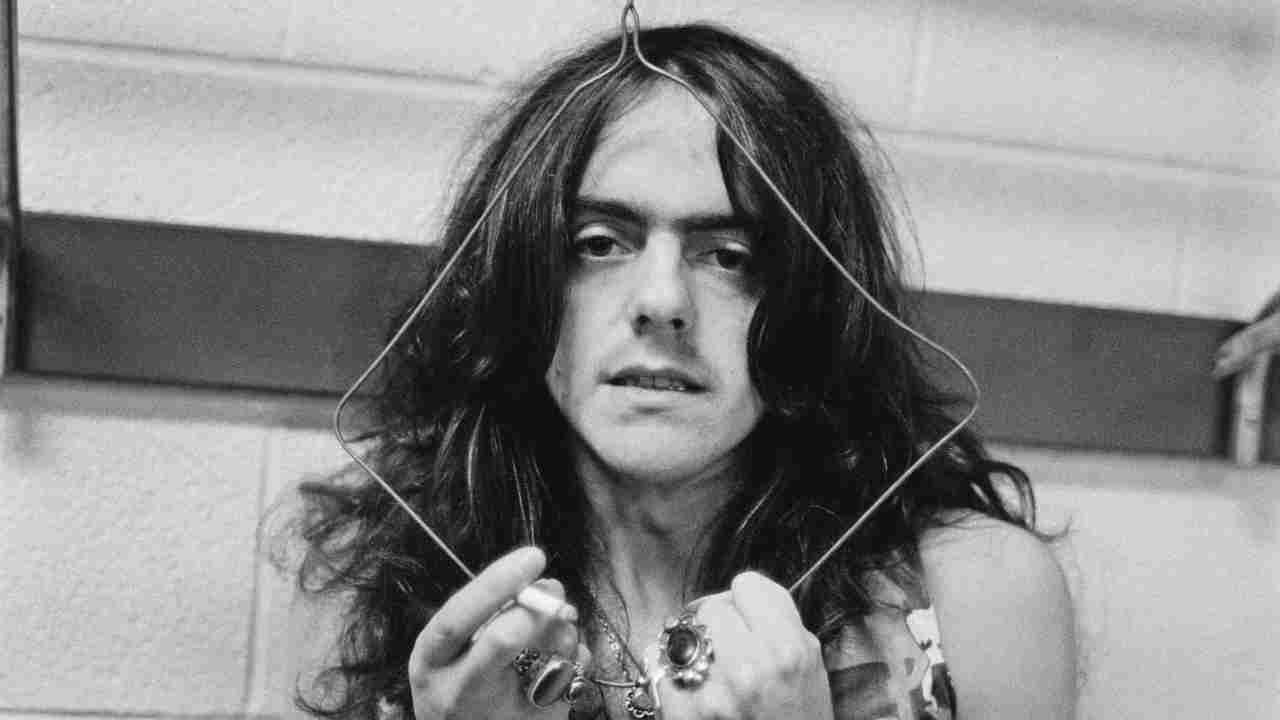

Bain was born in Newtonmore, Scotland in December 1947. He cut his teeth with such bands as Nick And The Sinners, The Embers and, after his family emigrated to Canada, Street Noise. In 1974 he returned to the UK and founded Harlot. Classic Rock photographer Ross Halfin, then a teenager, became friendly with Bain at the the time.

“Jimmy would sneak me and my friends into the Marquee or buy us pints up the road in the Ship because we were too young,” Halfin recalls. “He was a genuinely nice guy. Even later on, you always felt welcome with him wherever you were. It was probably a Scottish thing.”

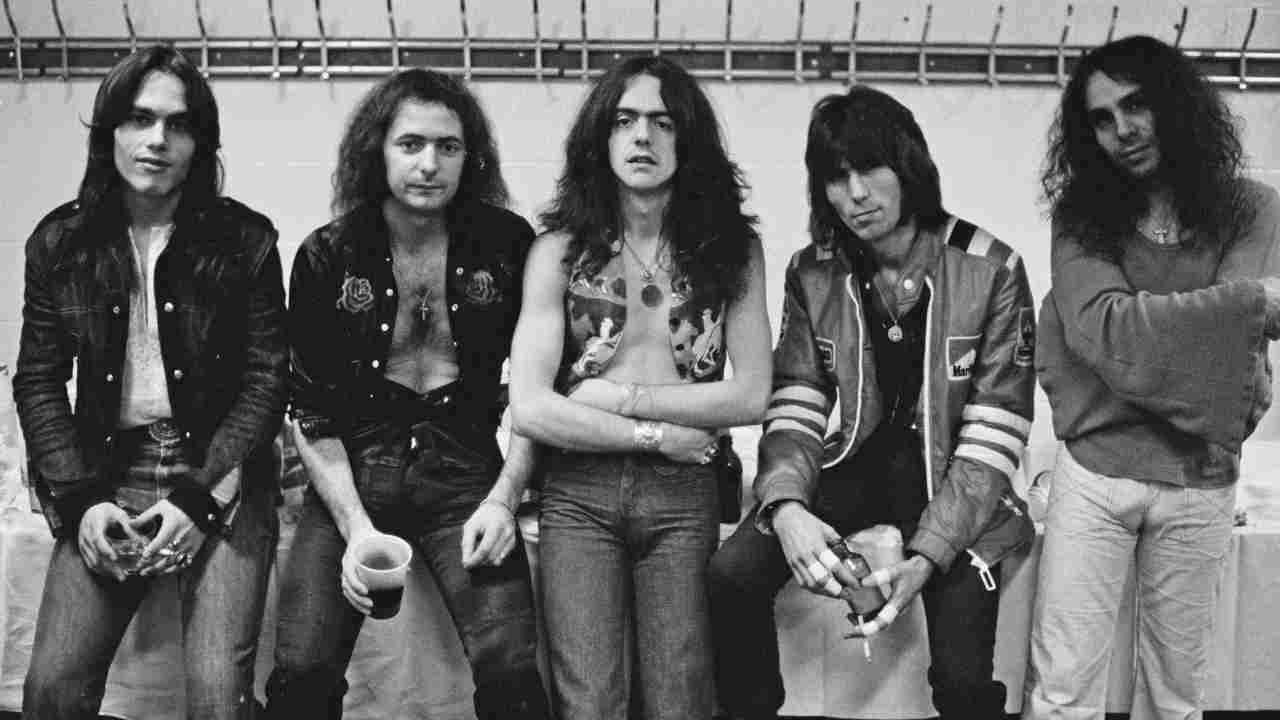

Bain’s break came when Ritchie Blackmore saw Harlot at the Marquee in the summer of 1975. While the band were a shambles that night, the ex-Deep Purple guitarist was impressed enough with Bain to offer him a job with his post-Purple band Rainbow. It was in Rainbow that he met keyboardist Tony Carey.

“Jimmy and I became the terrible twosome and got into all sorts of scrapes,” Carey says of his bandmate, who later served as best man at his wedding. “My first lesson in rock’n’roll economics came when we visited a lawyer’s office to sell our souls for the next million years. My contract said simply that the terms and conditions of my employment were the same as those of Jimmy Bain, and Jimmy’s document repeated it in reverse. We were paid peanuts, but we didn’t care.”

Bain’s tenure in Rainbow lasted just two years and one studio album, the groundbreaking Rising. In 1977, following a Japanese tour, he and Carey were given their marching orders.

“Maybe they thought I was drinking too much,” Bain told Classic Rock in 2011. “It never affected my playing. I know it got wild and wacky in Japan, but we had been working our asses off for a year. We were winding down. I was kind of pissed off that I didn’t get to stay longer, but I can never say anything bad about Rainbow. I was only in it for two years, but it’s done me a lot of favours.”

Bain’s time in Rainbow marked him as a straight-down-the-line hard rock bassist. In truth he was far more versatile than that, though it would take his death to remind people of the fact. He worked with ex-Velvet Underground bassist John Cale in the late 70s, played on folk-rock maverick Roy Harper’s Unknown Soldier album in 1980 and appeared on several tracks on Kate Bush’s 1982 album The Dreaming.

But he was most at home when he was surrounded by like-minded people. He was friends with Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott, with whom he shared a fondness for pharmaceuticals. Lynott had Bain play bass on the track With Love on Lizzy’s Black Rose album. After Rainbow, he teamed up with guitarist and fellow Scot Brian ‘Robbo’ Robertson in Wild Horses. Robbo had just been ejected from Lizzy, and he shared the same cavalier attitude towards life as Bain. The new band allowed the bassist to indulge his two favourite passions: music and partying. It’s no coincidence that their self-titled 1980 debut album featured a song called Dealer.

“We were very much into substance abuse,” Bain told Classic Rock in 2008. “Back then, if somebody offered me something I’d take it first and ask afterwards what it was. Even in the Dio days, I’d swallow a pill, wind up unconscious in the limo and have to be carried back to my room. I’m less crazy now, but it’s amazing I still have a brain.”

Life in Wild Horses was never dull. When Ross Halfin, by now working as a photographer, shot the band in London’s Ladbroke Grove, he was given cocaine for the first time, by Bain. “At home I couldn’t eat my tea,” Halfin says with a laugh. “My mum was furious.”

If Bain was a livewire, he was never malevolent. “The thing about Jimmy is that he always had a twinkle in his eye, he was a little imp,” says drummer Clive Edwards, who played in Wild Horses. “A wind-up was never too far away. You would never accept a cup of tea from him, because he thought it hilarious to piss into the kettle.”

Sadly, the friendship between Bain and Robertson unravelled over the course of two albums, and the guitarist quit following 1981’s Stand Your Ground. Robbo always regretted the decision to allow Bain to sing. “Steve Perry from Journey phoned us up out of the blue and said he wanted to join but we turned him down,” said Robertson (who declined to be interviewed for this piece). “What idiots!”

Bain tried to revamp Wild Horses after Robertson’s departure, but with no success. He was subsequently approached by the Scorpions to play on their Love At First Sting album when the German band were having problems with their bassist, Francis Bucholz. Bain’s name didn’t appear on the album, but the pay cheque made up for it. Bain was credited for his work with Phil Lynott on his solo albums, Solo In Soho and The Philip Lynott Album (a song he co-wrote for the latter, Old Town, was later covered by The Corrs).

If Bain was unhappy with life as a jobbing sideman, he didn’t show it. And once Ronnie Dio re-entered his life, it didn’t matter.

Bain was just winding up Wild Horses when he got a call from Ronnie in 1982 asking if the bassist knew any good guitarists for a new band he was putting together. Dio later suggested that Bain had misunderstood him – that he was looking for a guitarist, not a bassist. “Jimmy took it on himself to bring his bass and kind of made the assumption he was in too,” he later said.

Irrespective of how it came about, Bain proved to be an integral part of Dio the band for seven years, from 1982 to his departure in 1989 (he was with them again between 1999 and 2004). As well as contributing to some of their most pivotal songs, including Stand Up And Shout and Rainbow In The Dark, he made good on Ronnie’s request about guitarists. Jimmy remembered a young Irish hotshot named Viv Campbell, whose band Sweet Savage had supported Wild Horses.

“At three a.m. one morning the phone rang, and my father answered,” Campbell recalls now. “He said: ‘A drunken Scotsman wants you.’ Jimmy was with Ronnie and Vinny, and asked whether I could go to London for an audition the following day.”

Campbell is speaking to Classic Rock from Miami, just three days after Bain’s death. He’s understandably emotional, though the warmth in his voice conveys a fondness for his old friend.

“Jimmy was a generous man who’d give you the shirt off his back,” says Campbell. “He could be the clown, the drunk, the drug addict, but he had a very kind and gentle spirit. You could see how he would bump into Roy Harper or Kate Bush and the following day be in the studio with them. His persona made people want to hang out with him.”

Bain and Campbell’s respective original runs in Dio ended acrimoniously amid disputes over money. But there were good times too. The guitarist’s favourite memory dates back to sessions for the band’s debut album, 1983’s Holy Diver.

“We were listening to a playback of the song Rainbow In The Dark, but it lacked that final element to fulfil its potential,” says Campbell. “So Jimmy wanders over to a Yahama DX7 keyboard in the corner of the room, a drink in his left hand and a cigarette in the right, and, still holding the drink – and the cigarette between his lips – proceeds to play that lick everyone now knows. A real keyboard player would’ve put down the drink and cigarette to create something overly elaborate, but what Jimmy played was perfect.”

After Dio, Bain resurfaced in LA band World War III alongside Dio bandmate Vinny Appice and singer Mandy Lion. But the halcyon days of 80s heavy metal were fading. Bain found himself swimming against the tide.

“WW III was a pretty extreme band, and the belief of someone of Jimmy’s stature brought so much additional strength,” Mandy Lion says today. “He partied harder than us all, he had more sex than anyone – one night it would be a model, twenty-four hours later the cute grandmother that drove the limo. Jimmy was every rock-star cliché made flesh. He lived every moment like it was his last.”

In truth, the 90s and 00s weren’t easy for Bain. After leaving World War III, he tried to get a new band, 3 Legged Dogg, off the ground, and played with the Hollywood All Starz alongside members of Lynch Mob and Quiet Riot. Motörhead guitarist Phil Campbell became close to Bain after his own band relocated to LA in the 90s.

“We’d go to one another’s houses and drink, and of course we played music together with our bands,” Campbell recalls. “When I first knew Jimmy he had a big house with a swimming pool. And then he got divorced and, unfortunately, everything changed.”

His personal life may have been a mess, but Bain retained his sense of humour. “Jimmy’s dog went missing, and he asked to borrow my car for an hour and a half to drive around and look for him,” says Campbell. “He then dropped off the radar. Three days later I still couldn’t get hold of him. I left an angry answerphone message demanding we meet at the Cat & Fiddle, an English pub on Sunset Boulevard. Eventually he comes in, screaming at me – they say attack is the best form of defence. I found out the dog was at the house all along; he’d just needed a car. It was typical Jimmy.”

It was an altogether less humorous automobile-related incident that put Bain back in the headlines in 2012, when the bassist was arrested for DUI (drink-driving) twice in one day in LA. He was driving a 1995 Toyota Camry, a wreck of a car, which only underlined the situation he was in.

“The sad truth is that Jimmy really couldn’t take care of himself,” says Viv Campbell. “He didn’t pay much heed to the demands of real life. By the end he was almost living in poverty. That’s why he was so excited about Last In Line.

Bain had reunited with Campbell and Appice as Last In Line in 2012. Originally playing songs they’d recorded with Dio in the 80s, by 2014 they had enough original material for an album.

“Even during those later days, which you might describe as his wilderness years, Jimmy never gave up hope and would always have a bass or a guitar with him,” says Campbell. “He still wrote songs. Someone less determined might have said bollocks to it, but he lived and breathed for music and was never more than a few feet away from an instrument.”

“Quite recently Jimmy wrote a song called Victims. It was something that George Michael could have recorded,” adds Clive Edwards. “Jimmy had more to say than ‘I want to rip your knickers off’. His natural writing style had more in common with the work he did with Phil Lynott. He wasn’t just a horns-up metal guy. He wasn’t even a metal guy at all.”

Everyone who knew Bain says that he had turned things around before he died. “Jimmy really was sober for around eighteen months,” Viv Campbell stresses. “While we worked on the Last In Line record, he was in a halfway house where you are tested for drugs and alcohol after his DUI incident. We had to schedule some of our activity around him, because he was only allowed out after four p.m.”

According to friends, Bain was being treated for pneumonia, but he didn’t know he had lung cancer. “Jimmy called me two days before he died,” says Mandy Lion. “He wanted to console me after my dog died. Not a word was mentioned about his illness.”

While he was clearly unwell when he boarded the MSC Divina, no one knew how serious things were. “I think Jimmy just wore out,” Tony Carey says. “My dad went at sixty-eight, too, and he wasn’t particularly rock’n’roll.”

The last time Classic Rock spoke to Bain was at the end of 2015, for a tribute to mark the 30th anniversary of Phil Lynott’s death. He remembered a “very poignant discussion” he and Lynott had in a pub over Christmas 1985, a few days before Lynott passed away.

“We were still in our thirties, and neither of us could believe that we were still doing rock’n’roll,” said Bain “When you start out, you assume that it’ll all end in your twenties. So we had this conversation about how fortunate we were, and how the two of us were still working on our musicianship – trying to get better. And then just a week or two later Phil was gone.”

And now Jimmy Bain has gone too. Wherever he is, we hope that he’s happy.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 221, February 2016

![Dio - Rainbow In The Dark (Official Music Video) [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/PrBUjXaRSUQ/maxresdefault.jpg)