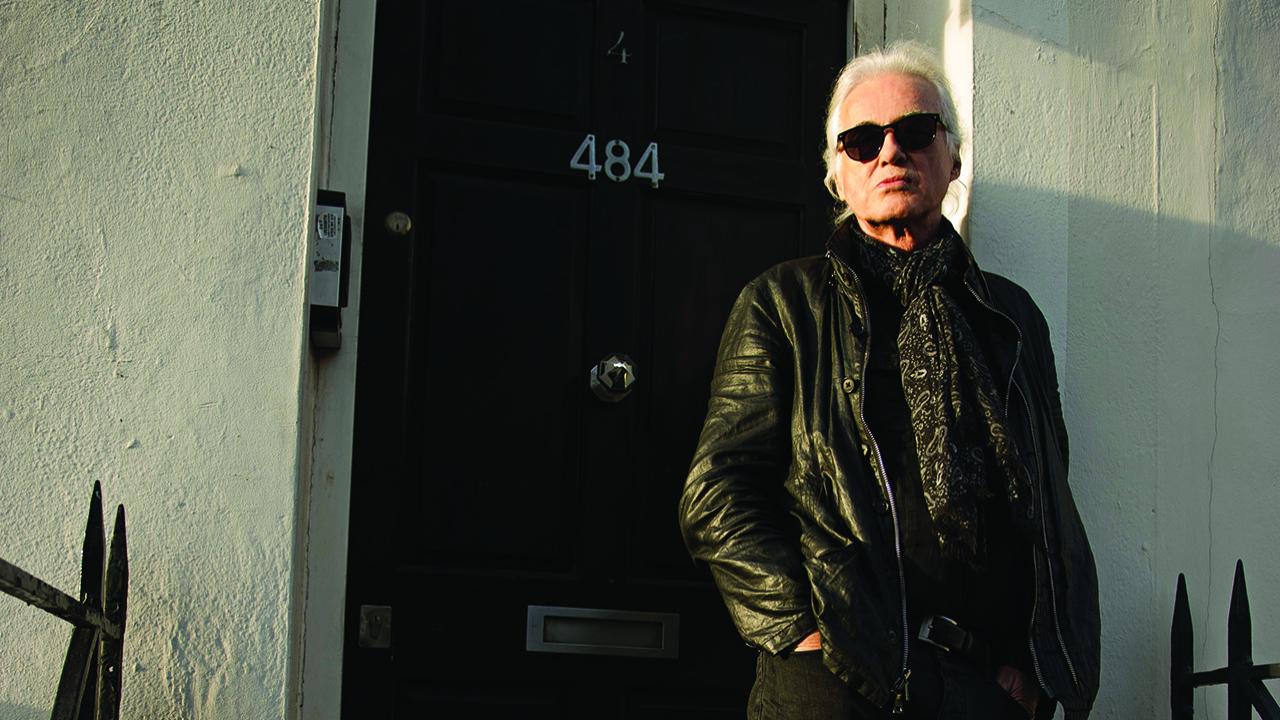

On a grey November afternoon, in a private room at the Gore Hotel in well-to-do Kensington, West London, one of the most famous rock stars in the world is explaining how it goes when people recognise him – in a street, at an airport, wherever he happens to be. “It’s this,” Jimmy Page says. He rises from his chair and does an impression of a Led Zeppelin fan, one hand outstretched for a handshake, the other hand reaching into a pocket for a phone and then arcing around for the inevitable selfie.

“That’s life,” he says with a shrug. And so it is when you’re Jimmy Page, the guitarist and leader of a band that was, in the 1970s, the biggest thing since The Beatles. And yet there are times, he admits, when fame can be an embarrassment.

For Page, it’s a pleasure to walk along Denmark Street, home to many of the finest instrument stores in London. He’s not really looking for any more guitars. He has enough of them. He’s just window-shopping. But every time he does, the same thing happens. As he gazes through a shop window, he will eventually notice the members of staff staring back at him from within, nudging each other, with the same expression on their faces – an expression that says they smell money.

It begs the question: what if Jimmy Page went into one of those guitar shops and saw that famous sign on the wall: ‘NO STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN’. What then?

“I’d probably go in there and play Stairway,” he laughs.

You think so?

“You’re asking me the question,” he smiles. “I’ll give you a humorous answer.”

Laughing, joking, Page is evidently in a good mood today. Partly, it’s because he’s demob happy at the conclusion of a two-year promotional campaign for the reissue of Led Zeppelin’s nine studio albums, all supplemented with previously unreleased recordings, the entire project curated by Page. Also, he’s delighted at Zeppelin’s success at this year’s Classic Rock Roll Of Honour, winning the award of Reissue Of The Year, a category in which the nominees included The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Deep Purple and the Rolling Stones. This was the result of a public vote, and Zeppelin won by a landslide. “That,” Page says, “is just wonderful.”

The Gore is a favourite meeting place of his, close to the Grade I-listed house that he’s owned since the early 70s. The decor of the hotel’s Gothic Room suits his taste, a wood-panelled lounge, softly lit. In these comfortable surroundings, Page has a relaxed demeanour, in contrast to the last time he spoke to Classic Rock, in July, when the final instalment of Zeppelin reissues was released. Then, the discussion centred on the end-stages of Led Zeppelin: the dark days culminating in the alcohol-related death of drummer John Bonham in 1980, which finished the band. In that conversation, Page was guarded and elusive. Not so today.

In a conversation lasting an hour and a half, there are moments when Page becomes a little tense, most notable in his measured response to a recent comment from Keith Richards, in which he described Led Zeppelin’s music as “hollow”. Page is acutely aware of how these things play out in the media. But for the most part, he talks freely and openly about the various aspects of his life and work, inside and outside of Led Zeppelin.

A waitress brings coffee with cold milk and artificial sweeteners for Page. “A little fuel,” he says. “Now, what do you want to know?”

Let’s begin with how you’re feeling after the dust has settled on the Led Zeppelin reissues. Is there for you a sense of finality, and sadness, in this?

No, no – it’s more a sense of relief, actually. I’m really pleased that it’s done, and done properly.

Meaning what?

It’s a serious package. Other people have done reissues with bonus tracks, but nobody had ever gone right though the whole of their catalogue and added so much extra material, and that’s so important to me. I knew it was going to be really well-received by all the Zeppelin fans. I just knew that. And to win this award from the Classic Rock readers, you figure that the people have been able to hear what it really is.

Where exactly did all this extra material come from? I like to think you had it locked away in a dungeon.

Well, I’ve been pretty careful with all the tapes I’ve stored over the years – all quarter-inch analogue tape, which needed a lot of tweaking. I also checked what was in the Led Zeppelin storage as well. Robert [Plant] had a few tapes, but most of it I already had.

Is it true you went to a lot of record fairs to find out how much of this rare Zeppelin material was already out there on bootlegs?

Yes. Going to record fairs, I was researching everything purported to be Led Zeppelin studio recordings. I wanted to make sure that all of the things I thought I’d kept securely had never been leaked out.

And?

Obviously there were some things that were bootlegged. But what I had on those tapes, I knew that a major percentage of this stuff had never been heard before – not even by the other members of the group, because there are times when you do something on one night and that’s the end of it. So I knew that this project was going to blow all that bootleg stuff out of the water.

The guys at record fairs selling Zep bootlegs – were they embarrassed when you showed up at their stalls?

I’m not going to get into that. Let’s just say that in Japan, I went to a lot of bootleg stores when I was researching. And after the reissues came out, I’d go into those stores and they weren’t quite so enthusiastic when I walked over the threshold.

Of all the tracks that you pulled from your archive, one of the very best is St. Tristan’s Sword, recorded in 1970 and included on the new version of the album Coda. It’s such a funky track, and you really cut loose on it.

Yeah. We were stretching out on it. It could have been a proper song, but we were just jamming, and in the end that’s how we left it.

The title of that track is enigmatic. Where did it come from?

I think it was something related to Arthurian knights. Put it this way [miming swordplay], it has a thrust to it. And this track, nobody knew it was recorded. There were no bootlegs of it. This was the beauty of having really guarded what you had.

Was there, in all of this, one treasured recording that you held back – something that’s for you and you only?

No. To do this honestly, you had to put everything out there that you knew was really good – all the gems. No holding back. With the studio stuff, this is absolutely it. And I left no stone unturned. Any project I’m doing, I do it like that. And so, at the end of it, even the guys in the band were definitely in for quite a number of surprises.

There is, though, one notable omission from this project: The Swan Song. Of all the Led Zeppelin tracks that remained unreleased in the 70s, this is the Holy Grail for Zep freaks.

It was a long piece, lots of guitar. I did have a multitrack tape of that, with orchestration and Mellotron and all this stuff, but it got mislaid. I don’t know what happened to that.

But you did use a part of The Swan Song as the basis for a different track, Midnight Moonlight, recorded with Paul Rodgers in your 80s supergroup The Firm.

Yeah. It was sort of scaled down a bit when I did it with Paul. We concentrated more on the rhythmic parts of it.

Was the lost Zeppelin recording better than that?

With the Zeppelin version, we were really just sketching it through, sometimes just to remember things, and so you get through all the different parts, you play it faster than you may do it when you settle down for the real recording. So we did a quite spirited version of it, if you like. But it never got any further than that. It didn’t become a song, but it became the title of the record company [laughs].

It’s a little sad that this mythical song slipped away.

Really, it’s more a question of what did turn up. All of the things I was looking for turned up during this project. So it was great.

For Page, the curating of Led Zeppelin’s catalogue is a labour of love that began as far back as 1982 with Coda, an album he compiled from outtakes cut between 1968 and 1976. “It was a contractual album,” Page admits. It was also, on a deeper level, a memorial to John Bonham and to Led Zeppelin.

At the heart of Coda – “the backbone”, as Page calls it – was Bonzo’s Montreux, the drummer’s explosive showpiece, recorded in 1976. “This was something that John had talked about for years,” Page says. “It was like a drum orchestra. And, of course, with John’s application to things, it was quite brilliant.”

In this, Bonham had a fitting epitaph.

What Page remembers most clearly about the making of Coda was how much it took out of him. “It was only two years since John died,” he says. “It feels, in retrospect, very close to losing him and going through that stuff. And, of course, it’s with a heavy heart that you put out an album where John is no longer alive.”

And yet, by the time this album was released in ’82, Page had already begun to rebuild his career in music. He had not yet reached 40. There had to be something out there, a life after Led Zeppelin…

In December 1980, when Zeppelin’s split was made public, were you even able to contemplate the idea of making music without the band?

To lose John was such a bitter blow to everybody – everyone from his family and his musical compatriots to all the fans. It was such a great loss to us all. And I wasn’t really keen to be thinking about doing anything.

In the end, what changed?

I got a call in 1981 from Chris Squire and Alan White [Yes bassist and drummer]. I had a recording studio, they were working in there, and they said, “Do you want to do something with us?” When I went in there, they’d already rehearsed their stuff, and oh my goodness, they were superb. So I played with them, and doing that, it was so therapeutic.

So you formed a supergroup.

It was Chris who had the idea to call it XYZ, because it was ex-Yes and ex-Zeppelin. I think they rather hoped that Robert might come in on it too. But Robert, obviously, was doing his solo career.

Disappointingly, XYZ didn’t last long enough to get a record made. Why was that?

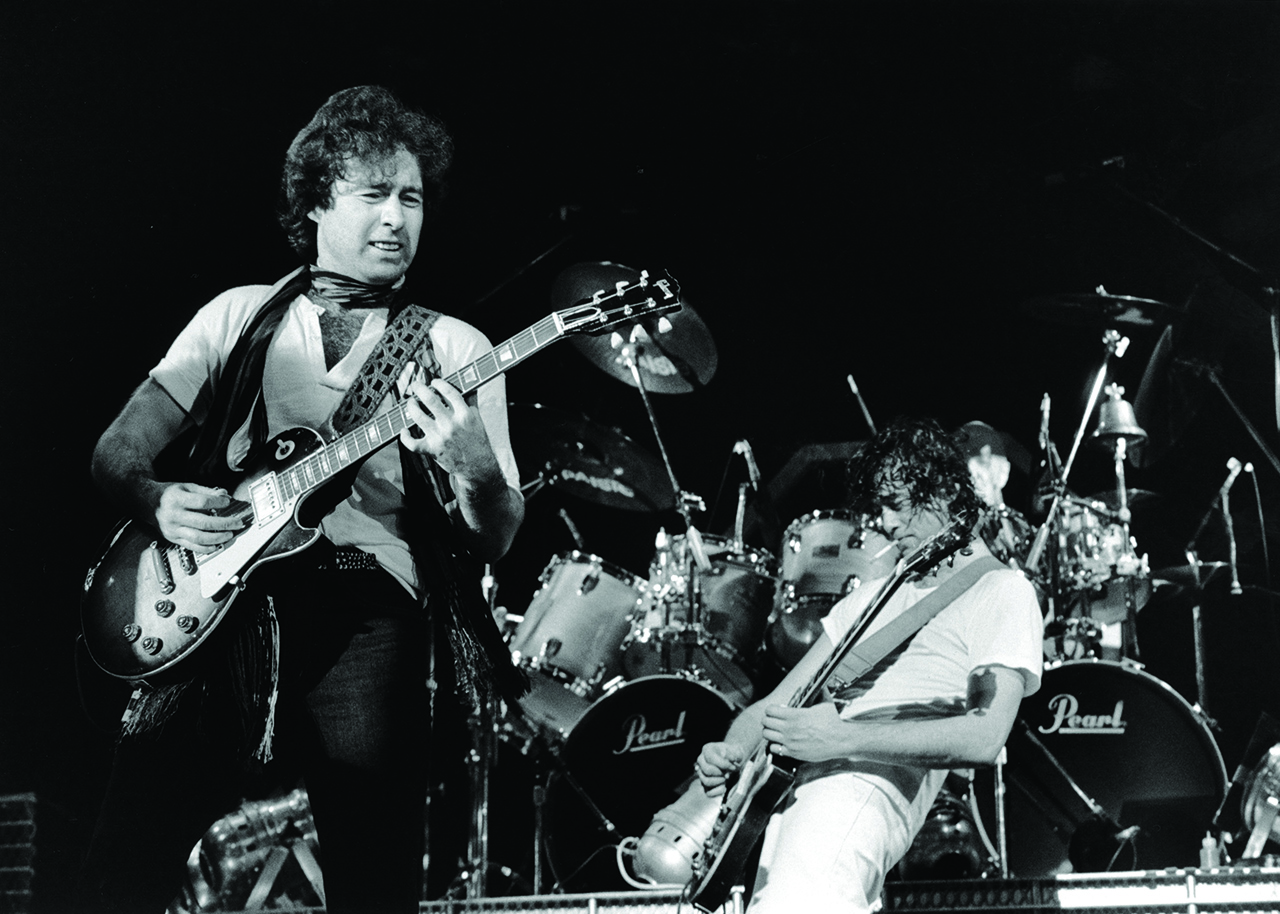

It just fell apart. I think Chris and Alan had another Yes tour coming up, so off they went [laughs]. But nevertheless, it was really good stuff that we did together. And boy oh boy, was it the right thing to do. Rather than tinkering around at home, it was like, whoah – you’ve got to really cut it with these guys, because they’re just so good. It was brilliant for me to do that. And from that point, I did the film soundtrack for Michael Winner [Death Wish II]. So I did two really major things at that point. I had to really put everything I had into both of those projects. And that’s what got me going again.

If you think back to the period immediately after John’s death, were you grieving not only for him but also for the band?

Oh, without a doubt. Everyone played so brilliantly individually, but as a band it just went up and up and up. We played uniquely as a band, you know? And it was such a joy for us to play together.

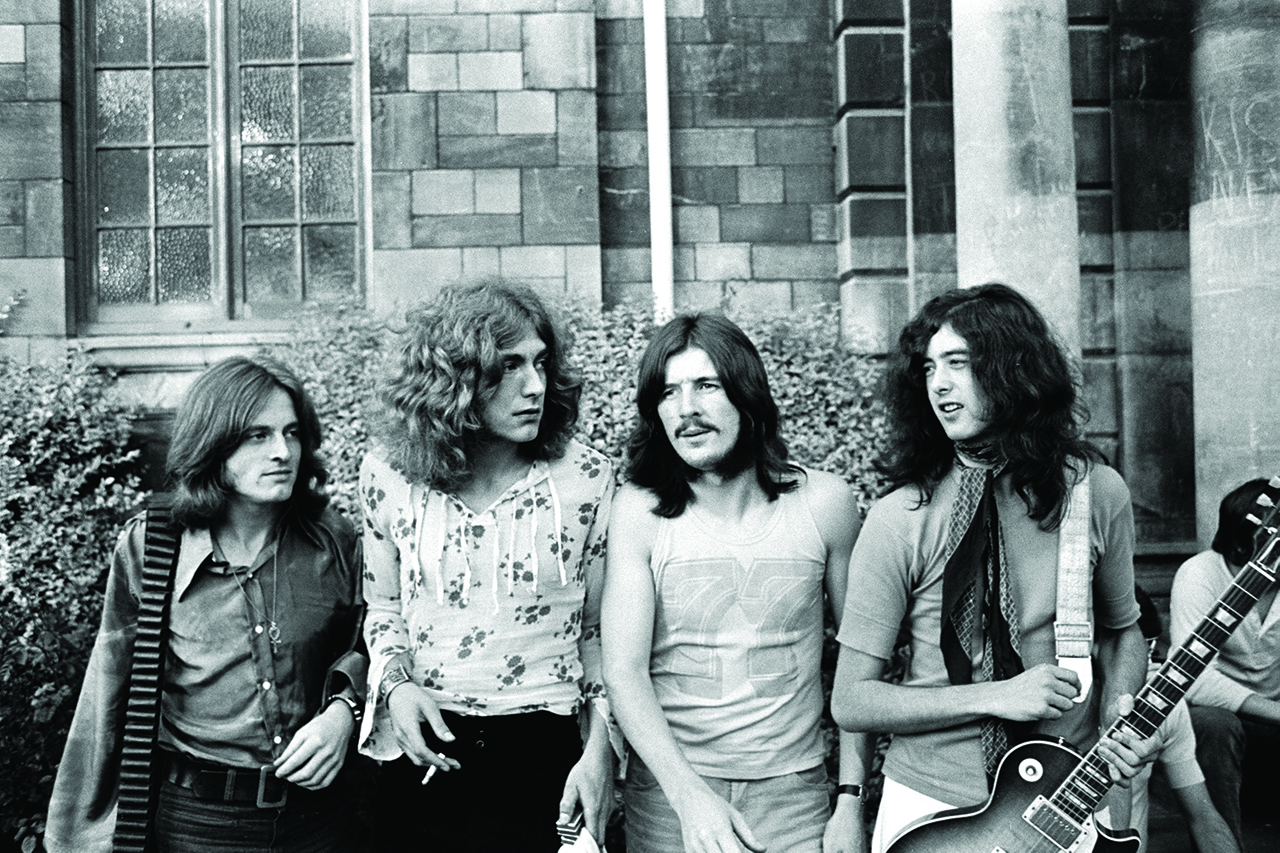

Was there a defining moment in the band’s career when you thought that what you had created in Led Zeppelin was everything you’d ever dreamed of?

The first album, because I knew how groundbreaking it was. The way the whole thing was put together, the way that it was layered and mixed, and the way that the drums were to the forefront – the big, complete stereo picture – I knew that nobody had ever done this. We were touching so many areas. We were touching the blues, we had what people would call rock, and we’d got avant-garde stuff going on, with the bow on the guitar and the recording techniques that were on there, the backwards echo, so many things that hadn’t been approached that way before. So yeah, a defining moment.

Is there one song from that album that really stands out for you?

Babe I’m Gonna Leave You. At that time, it was such a movement forward. And Robert’s singing on it is just fabulous. But that whole album was a complete barrage of ideas. It’s got so much energy to it, and yet there are so many colours in there too.

Was there a strategy in how the music was developed from one album to the next?

I did have a sort of game plan that I hoped would work, and it did work. And it was all pretty brave and risky stuff. With the first album, that sort of blueprint gets laid down. The second album, to actually record some of it while we were on tour, to get the energy from being on the road, I thought was really cool. And after all that high energy – after that inhale – you hear the exhaling on the third album with all the acoustic stuff. The plan was to expand and open up, and we went right over the horizon…

When you’re the leader of the biggest band in the world, selling millions of records, playing in stadiums, can it get lonely?

At that time, I was just living it. Living what it was, and really enjoying it. It was so exhilarating being part of something like that – something that was even changing the way people listened to music, let alone how they played and constructed it. But I had a yin-yang sort of life. I lived in the countryside, and that was my retreat when I came off the road, so the pendulum would swing completely the other way. It was so crazy on the road, the whole adrenalin of it, the sleepless nights and all the rest of it. That’s how it went – at least it did for me. So I welcomed the tranquillity of being off the road, being with my family or whatever. But it wasn’t like I switched off. I kept going, writing things, always thinking towards the next stage. I was consumed by it, all the time.

At the height of it, did you ever feel you were losing your mind?

No. But I’ll tell you what it was like: it was like something exploding that keeps expanding. It just didn’t shut off.

Is there one Zeppelin song, above all others, in which you can hear that explosion in your head?

I’ve never been able to put on Achilles Last Stand without thinking, “My God. I really was on fire there.” The power in that song is just amazing. There’s a great narrative in the story that Robert was telling. And Bonham’s drumming is out of this world.

Isn’t it difficult to listen to that stuff, hearing the band at its peak, with Bonzo thundering away as only he could?

Yeah. When I was working on the reissues, there were times when I felt melancholy, in so much as I couldn’t call John and say, “Hey, have a listen to this!” But to hear his playing, this amazing musicianship that has inspired millions, that’s a wonderful thing.

It seems like the only man on Earth who didn’t rate John Bonham is Keith Richards.

Really? What did he say?

The gist of it was this: “Jimmy Page is a brilliant player… but with John Bonham thundering down the highway in an uncontrolled 18-wheeler… I always felt there was something a little hollow about it.”

Hmm. You know, Keith can say what he wants. He’s Keith Richards. I think he’s done some amazing work. I respect his playing. And he has a solo album out. But if I was promoting a new album, would I be more caustic? The answer is… no.

It could be worse. He described the Grateful Dead in two words: “Boring shit.”

That’s funny. But I’m not sure what he means by calling Led Zeppelin hollow. I think he’s got his tongue in his cheek.

And really, Led Zeppelin didn’t do too badly.

[Laughs] No. What we did was really cool.

That last comment might just be the understatement of the year, something to go along with Reissue Of The Year. But for Jimmy Page – for now, at least – Led Zeppelin is a thing of the past. Ever since the band reunited for a one-off performance at London’s O2 arena on December 10, 2007, with John Bonham’s son Jason on drums, Page has been frustrated by Robert Plant’s refusal to engage in a full-scale comeback tour. Eight years on, nothing has changed. Plant remains dedicated to his solo career. And for Page, this is also the way forward. In a sense he’s back to where he was in 1980. Led Zeppelin is over. It’s time for Page to move on. And now, at last, he says he’s ready for that challenge.

You said in 2014 that you would be back playing live again in 2015. Why didn’t it happen?

What happened was this. I’ve been busy with the Led Zeppelin stuff over quite a number of years. If I’m going to pay live, I really need to be seen to be playing with, I guess, other musicians. And if I’m paying musicians, I don’t necessarily want to be sitting in a studio going through loads of old stuff – I want to be doing what’s current.

Where are you at now, in terms of a new band and new music?

It’s not like I’m a year behind. I’m a few months adrift, because I really hoped to actually be up and running at this point. But I will be next year.

Really?

Definitely. I’ve got to. That’s exactly what I’m about – I love playing live. But there are so many different aspects and characters to my playing, so many areas I can go – acoustic, electric, experimental – that I’m just working on the guitar, to work out what way I’m going to go.

I won’t ask for names of musicians…

I haven’t got any names.

You haven’t got anyone confirmed?

No.

Could you see yourself doing something like The Firm, where you have a singer of equal stature in Paul Rodgers?

Paul is brilliant, isn’t he? But can I tell you exactly what my plan would be right now? I’m not thinking: who’s the singer going to be. That’s the last thing I’m thinking about. My plan would be to work on all of the music, so that by the time I get the musicians in, I’d be sure that the music is really substantial in all these areas, because some of it is going to be tricky. I want it to be pretty unusual.

Unusual in what way?

I want to surprise people. But I would definitely do something outlining my history – past, present and future. On my solo tour in 1988, I did stuff from The Yardbirds, Led Zeppelin and The Firm. I wouldn’t do anything too dissimilar now. I’d do things that I know people would want to hear. But I’ve got new music as well.

Can you tell me about it?

No. [Laughs] You, and everyone else, have to wait.

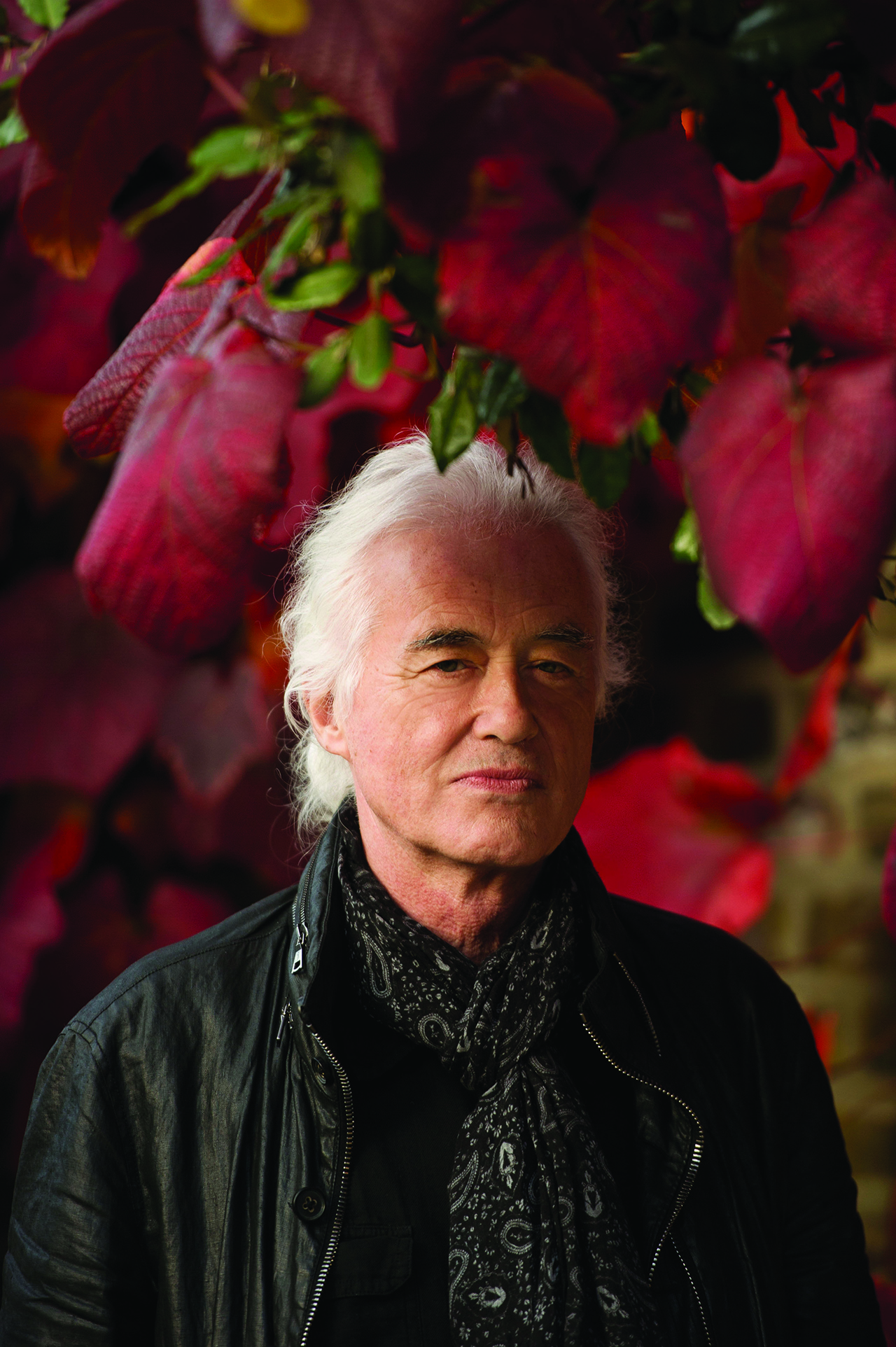

It’s been a long wait. And seriously, now that you’re into your seventies, do you feel the time running away from you?

Well, none of us are getting any younger. There are some who are total phenomena, like Jeff [Beck]. He’s the fountain of life. But for me, making music, getting it right, it needs a lot of preparation, a lot of work.

So when you finally get back on stage, how nervous will you be?

Listen, if I’m well-rehearsed and I’ve got the things there that I think I’m going to have, all the elements of it, yeah, I should be fine. But it’s an exciting prospect, so the adrenaline tap will start leaking beforehand. So it’s not necessarily a negative thing, the nerves – it’s more something you can harness. The adrenaline rush is quite something, the anticipation of waiting to get out there.

But it wouldn’t feel quite right if you didn’t have a tingle of nerves?

Oh, no. Of course I’d be nervous. But I wouldn’t do it unless I felt that it was really something. Standing up and being counted, you want to get a pretty good score.

Page laughs again. In this conversation he has laughed often. And with the interview done, he’s happy to continue talking for another 20 minutes. Mostly he talks about music. He says he was “blown away” by a recent U2 show, with its dazzling special effects. He admits that he hasn’t had time to listen to much new music, but there is one album from 2015 that left a big impression on him: Bob Dylan’s Shadows In The Night, a collection of standards popularised by Frank Sinatra. “I just love the way Dylan’s voice sounds now,” he says.

His face lights up when he talks about this stuff. You can see he’s being honest when he says: “Music is such a passion for me, now as much as it ever was.”

And before he leaves, a final question. Earlier this year, Page said that he was writing his autobiography, but stated that this would only be published after his death. Was he joking?

“No,” he says. “I meant that. And I meant it for two reasons. Firstly, you can really write what you want to write. And secondly, you don’t have to promote it. It’s funny, but it’s true. People say you can get around the truth, but no, I want to tell the story exactly as it was. Because I tell you what, the Led Zeppelin history seems to get changed quite a bit. It mutates. You go, ‘Wait a minute – that’s not true.’ And people say, ‘But I read it on Wikipedia.’ ‘Did you really? I see…’”

So the book is written?

“I haven’t finished it.” Another laugh. “I suppose I’d better not keel over just yet…”

The Led Zeppelin reissues are out now on Atlantic.