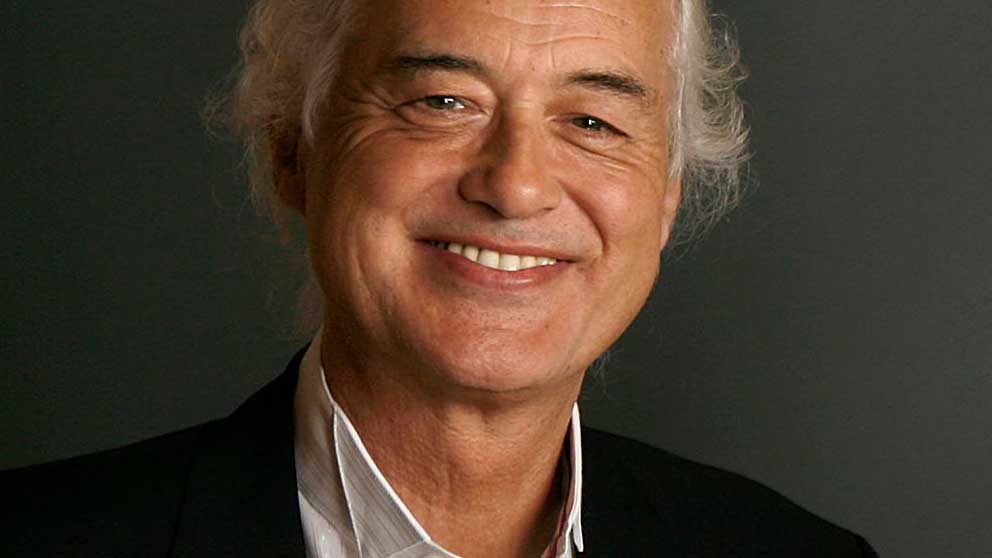

"Shirley Bassey arrived, took off her coat and went straight into the studio. She sang and then just collapsed on the floor": an epic Jimmy Page interview

As Led Zeppelin prepared for their 2007 reunion show, Jimmy Page sat down with Classic Rock for an extensive interview. And now, for the first time, we're publishing it online in full

When Led Zeppelin announced their Celebration Day reunion show in 2007, it seemed that everyone from Stephen Fry to Paul McCartney and Sigur Rós came out of the closet to declare their unconditional love for the band.

Apart from the obvious, what made this monumental get-together so special was that it wasn’t pulled together by the lure of filthy lucre or some condescending, world-saving crusade. The reasons were twofold. First and foremost, it was as a nod of respect to Atlantic’s founding father Ahmet Ertegün (monies raised went to a school foundation set up by his wife). Secondly, and equally as importantly, it was a chance for Zep’s surviving members to show a new generation of music fans what the fuss was all about. As Robert Plant declared: “We need to play one last great show.”

In this exclusive two-part interview, previously published in the January and February 2008 issues of Classic Rock, Jimmy Page tells the late Peter Makowski about the reunion, rehearsals, John Bonham, Live Aid, his session work and solo career, The Firm, Coverdale/Page and more.

The obvious question is, why did you decide to have the Led Zeppelin reunion now?

Why now? Mmm, I guess there was the clarion call with the tribute to Ahmet and for the charity that has been set up. Really it was a question of anytime, any place.

Originally there was talk of doing it at the Albert Hall. Then we thought we’d get together, in a clandestine location, to see how we all got along playing together. That was really good, but before we even got in there it was leaked that we were going to do the O2 whether we were any good or not! [Laughs.] But we had a really good time during that initial rehearsal with Jason. And then we had another get-together to pick over the numbers that we’d do relative to a set.

Originally it was proposed that we would do an hour, but there was no way that we’d do only an hour. So that stretched to 75 minutes, then 90 minutes and beyond. By that point we were going to make a joint statement, then it got leaked again. So the expectations are accelerating, but it’s okay. We’ll be rehearsing all the way up to O2.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

How are the rehearsals going?

With attitude! One of the things we agreed on was that if we were going to play together then we’d put as much into it as we possibly could. There had been a couple of previous get-togethers like Live Aid, which involved a couple of hours’ rehearsal in one of the dressing rooms with a drummer we’d never played with before, and then getting on stage with another drummer we hadn’t played with. It was totally shambolic. So this time it’s important that we are well prepared.

Live Aid was quite a risky venture for you to undertake. You had no control over the environment and a short set.

I think we came together in the spirit of Live Aid. At the time Robert was out on a solo tour and I was probably out with The Firm and it was a bit of a wing and a prayer. Sometimes those things can be a glorious success or it can be a glorious shambles [laughs]. You have to understand other people had taken it on properly, rehearsed and it showed.

Was it easy or difficult to pull this reunion together?

Well, the key to it was actually getting in a room together, playing together, going through a number and just getting the feel of the whole thing. That was the purpose of the first rehearsal, to see how we would all get on. There is that camaraderie, if you like, that we had but there’s been a lot of water under the bridge. It was really important to see how we would all get on. But the key to it is the music, because the music is so powerful. You have to throw yourself into it, the way you might throw yourself naked into a bed of stinging nettles. It’s a commitment.

What would John Bonham think of this reunion?

He would be absolutely so proud of Jason. In rehearsals Jason has such an infectious enthusiasm that it’s undeniable. The most important thing that you must never forget is that John Bonham loved Led Zeppelin’s music.

There have been various petitions on fan websites for a selection of drummers including Dave Grohl. Did you ever consider anyone else for the job other than Jason?

The thing is that Jason’s more than proved himself as a musician in his own right. We played together before. He was on my solo album and toured with me in the 80s. He’s come into the situation as Jason the man as opposed to Jason the kid and he’s certainly playing in that capacity. Don’t forget Jason appears on The Song Remains The Same and he appeared with us at the Atlantic 40th bash and he played remarkably well. So within the framework of Led Zeppelin material there’s no other choice. In fact it would be insulting not to do it with Jason. He more than measures up.

Is this the only show you will be doing? Is too early to say what you will be doing next?

The current target is the gig. I mean, of course, everybody’s projecting this, that or the other and there was a massive demand for the O2 show.

Were you surprised by that?

I knew it was going to be big, but it was more overwhelming than any of us could have guessed.

Were you surprised by the general warm response from musicians and the media?

No, because the music was always well crafted from the first album. The albums and the live shows are two different aspects and facets of Led Zeppelin. But it’s the albums that people are more aware of because when was it we did our last proper show, 1980? So there’s certainly a young audience out there who like Led Zeppelin and want to experience the band in a live setting.

Has it been difficult picking material for the show?

Not really. Not at all, actually. But I’m not going to tell you what the set list is [laughs].

There are a lot of people who really want to see you perform but aren’t going to get the opportunity. Are you going to at least film or record the show?

I’m not sure about that. The most important thing at the moment is to do this gig with the spirit that it deserves.

It seems to the outsider that while John and Robert have been pursuing solo careers, you seem to have concentrated on working on and protecting the Zeppelin legacy with a series of remastered albums, compilations and, this month, an expanded version of The Song Remains The Same.

Absolutely right! As far as Led Zeppelin is concerned I’ve been very keen on making sure that things are right; taking care of the legacy, making sure that the live material came out, like How The West Was Won, and pushing to get The Song Remains The Same out on a DVD of a high standard.

It’s Friday, November 2, 2007, three days before the third ever Classic Rock Roll Of Honour, and this magazine has just been given some bad news. In an hour or two the story will be all over the world, shining out of web pages, burbling out of radios, squeezed into late-night editions of newspapers.

Once again, Led Zeppelin are making headlines, and for Classic Rock they have very serious implications: Jimmy Page, it turns out, has broken a finger. Zep’s comeback gig will have to be postponed, and – just maybe – Jimmy won’t be able to make it to our awards. Ulp! Steven Tyler has already flown in from Boston. At Gibson HQ there’s a Les Paul specially signed by Les Paul himself, waiting for Jimmy.

Somewhere in Luton, an editing team is beavering away on the short film covering Page’s enormous career that will be shown to the room before Tyler presents Jimmy with his award. Somewhere in America, Aerosmith’s right-hand man John Bionelli is making the six-hour drive from his house to Joe Perry’s ranch to video some congratulatory words from Joe and email the footage to the guys in Luton. The Classic Rock team have polished their shoes an’ everything. Is it all going to be in vain?

Within hours the panic is over. Of course Jimmy’s coming, and he'll collect the Living Legend Award – he just won’t be shaking too many hands.

So how’s the finger?

It’s mending really, really well. I don’t want to jinx it but the specialist says it’s healing as nicely as could be expected in the space of a week. At least it looks like a finger again [laughs]. But it’s had a fracture, which is a bloody awful thing to happen to a guitarist – especially given the timing. There were entire years when it wouldn’t have made any difference, and then I have to fall over right before the gig at the O2. It’s such a shame it ended up inconveniencing so many people that were travelling to the show. I hope they’ll still come.

Your house presumably has an entire wing to accommodate the many awards you’ve received down the years. Is this one for Classic Rock’s Living Legend just another to add to the mantelpiece?

Good Lord, no. I’ve never attended an awards ceremony like it [laughs]. Good Lord, it was so heartfelt. It also meant a lot for so many of my peers to have been here. And we were able to have a bit of a laugh through seeing all that [video] stuff from when I was an enthusiastic 13-year-old. We all start off that way, don’t we, but not everyone ends up with all that stuff haunting them on YouTube. Then of course there were [messages from] Scotty Moore [Elvis Presley guitarist] and Les Paul… Heaven help us.

Was it emotional?

To be honest, I was choked when Steven [Tyler] did such an excellent speech. Then there was that whole wonderful tableau of images and it made me think: “Gosh, it is quite some career, isn’t it?”

Were you surprised by the fact that 20 million people wanted tickets for the gig at the O2?

Well, we knew that if the band ever did something that we could prepare for properly that it would be very popular, that it would sell out overnight. But nobody thought for a moment that there would be such an intense and overwhelming response.

Does that reaction make you a little nervous?

[Instantaneously:] Oh, no. Don’t forget that right up until the point of the finger intervention, we had some rehearsals. And we were right on – it was sounding incredibly good.

You must’ve received ticket requests from the milkman to passers-by in the street. Do you have a standard rebuffal?

Ha-ha-ha, it’s been difficult, you’re right. For so many people, Zeppelin was the high point of their musical lives. After so many years of not doing this, I’ve got many, many friends that I’d like to come and see the show. But it’s not a Led Zeppelin show, it’s a charity performance. I only had 20 tickets for my own family. Luckily, most people seem to understand that.

At the awards, Alice Cooper made an astute comment about market forces. He believes that because 20 million people tried to buy tickets to see Led Zeppelin, there will have to be some sort of tour.

[Smiling broadly:] That’s a crafty little question. But let me put it this way, our only existing target is the O2. Momentum is really strong, but I really can’t say what will happen afterwards.

This award recognises your achievements as a musician, songwriter and producer. Which role do you identify with the most?

All of it! Definitely all of it. I don’t think there’s one role that’s more important than the other. Going back to the beginning, what inspired you to pick up a guitar and form a band? I was seduced by the music I heard – because at that point in time it was so dynamic. It was of the youth and it was pulling me in. And I made every effort to follow what was going on at the time. I was a fan. We had a guitar at our house, but I had no idea what to do on it ’til someone showed me some chords and it went on from there.

Your first television appearance was on a show called All Your Own with a skiffle band – how did that come about?

I think somebody wrote off on our behalf to go on the audition. I remember being in the hall with loads of other kids and the presenter, Huw Wheldon, came in looking worse for wear and shouted: “Alright – where are those bloody kids?!” The parents were horrified – they were putting their hands over their children’s ears [laughs].

Did you have any aspirations to eventually become a full time musician?

No! We were grammar school boys from Epsom. One hadn’t put two and two together to realise that you could make a living out of your passion. At that time everyone was still genuinely a fan. It was exactly the same when I eventually got to meet people like Jeff [Beck] and Eric [Clapton] – they had been the only guitarists in their neighbourhood too.

In the early days what was the most unusual gig you’ve ever did?

Holloway Prison, when I was playing with Neil Christian and the Crusaders. Heaven knows how that happened. I remember we had to go to the warders’ office beforehand and we were put on a vow of secrecy not to reveal who we saw on the inside. The women in there had cotton print dresses in four different colours which were washed out. It was very interesting and really quite erotic. After we left there was a riot. It was probably because Neil Christian had wound the girls up. It was a terrific experience – though not quite like Johnny Cash at San Quentin.

Oh, I don’t know, I’d rather play Holloway than San Quentin.

Yeah, I suppose it did have its plusses.

When did you start doing sessions?

Well, I was in various bands before that but I got into doing sessions when I played in an interval band at the Marquee with a guy called Andy Wren, who was the pianist with Screaming Lord Sutch and the Savages. We never had rehearsals, we just used to go in there and play.

Actually, I can tell you a story about Andy. One night when he was in the Savages he came along with a flying-boot covered in bandages. Sutch would make references to it during the course of the show and say how fortunate we were to have Andy playing with us tonight, because he broke his leg and was in considerable pain. Then halfway through the show Sutch came on with this huge mallet and started beating Andy’s foot with it. Some of the audience jumped up on stage to try and stop him – of course, it was all a set up.

So, anyway, I was doing these interval shows and got headhunted at the Marquee. Someone came up and asked me if I would like to play on a record.

So what was your first official session?

It was Diamonds by Jet Harris and Tony Meehan – I played an acoustic on it. And the B-side was a written part and I just didn’t have a clue what it was all about. I could read chord sheets but not dots [musical notation] at the time.

During the 60s you did literally hundreds of sessions, and you have been credited with appearing on some of the most influential records of that decade. There are a lot of rumours and myths surrounding what tracks you actually appeared on. Is it true you played on The Kinks You Really Got Me?

No, I wasn’t on that. I played on some of the Kinks’ records but definitely not that one.

The Who – Can’t Explain?

I played on that but I wasn’t needed in the end [laughs]. Pete’s doing all the lead parts. I mean, there might be a couple of phrases on the B-side that you can hear me. But, to be honest, I don’t really know why I was there, except to just play along. Townshend’s doing all the important stuff. You wouldn’t have noticed if I wasn’t on it.

Them – Baby Please Don’t Go?

Yeah, I played on that.

Joe Cocker – With A Little Help From My Friends?

Yeah.

The Rolling Stones – Heart Of Stone?

I played on a version of that eventually surfaced. Also more recently I played on One Hit To The Body.

How about the iconic James Bond theme, Goldfinger, with John Barry?

That was a phenomenal session. John Barry had been rehearsing this massive orchestra and they were waiting for Shirley Bassey. When she arrived she just took off her coat and went straight into the studio. John Barry counted it in, she sang and then at the end she just collapsed on to the floor. And, I’ll tell you what, for a 17-year-old kid playing with an orchestra and watching all that happen was quite astonishing.

I’ve read that you were called in on some sessions just in case group members didn’t turn up or couldn’t deliver.

Yeah, I was a bit of an insurance policy. I was a hired gun and certainly in the early days a lot of the time you weren’t told who you were working with. But I was doing about three sessions a day, five days a week and sometimes at the weekend. And there was a constant change of venues as well – from Decca to Pye, EMI and Phillips. So there was a hell of a lot of stuff and I can’t remember everything I’ve done, but I think if I heard it I could recognise the guitar. And there’s a lot of stuff I did that I won’t tell you about.

Will we ever find out?

Yes, when my book comes out! [Laughs.]

Do you feel that your session work prepared you for Zeppelin?

It was like an apprenticeship and I treated it like that. Because as I’ve already said I didn’t read the dots when I went in. Initially it was a more a question of ‘play what you want and if you could come up with a riff that would be fantastic’. But it came to the point where they started giving out the musical charts, and it was going to be essential to be able to read them. So as I was learning to read music they would give me my charts first to give me a chance to become familiar with them by the time it came to rehearsals.

Over the forthcoming months I really became quite a reasonable reader, and if you can read music then you can write it and I ended up doing arrangements. You’ve got to remember that in those days a session musician was brought in to do everything across the board. It wasn’t like I was a specialist, although I was being pulled in on purpose to come up with invention, if you like. Because I had eclectic tastes I was pulled in on a variety of sessions.

What made you stop doing session work?

It was a muzak session. I can’t name what muzak I did or what lift it was being played in [laughs] but let’s just say it became hard work because you were just given a ream of musical notation and you just had to just have to read, turn up and make no mistakes, no reruns.

So looking back on it as far as the discipline in the studios was concerned, that aspect really served me well in my apprenticeship. And the fact that I was intrigued by the record production employed in the 50s, let alone the 60s. I was pulled in by it and I absorbed everything around me. Recording techniques were something that I paid a lot of attention to. I saw how to do it and how not to do it. I was an established musician but I needed to step aside – I wanted to play live again.

Moving forward to Zep, let’s talk about the debut album. Did you know it would work out so well?

Yeah, quite a while before it was recorded I knew exactly what it was going to be. When the album came out, it had so many ideas on it that were pretty unique [compared] to anything else at that period of time. It touched so many different areas that people hadn’t quite got to. The blues is on it, there was a bit of a reference to world music, there was folk music that had been taken out of any sort of sphere that had ever been approached prior to that.

And there was some really fine songwriting from members of the band. It was a classic debut album, which is what it should be. It was a new band saying: “This is what we’ve got."

When you recorded it were you fearlessly confident of what you were doing or were there any doubts?

Well, obviously, we didn’t just walk into the studios and pull it all together in a few hours. There had been a writing process running up to that and we had done some touring in Scandinavia as well. So we were playing very well together as a band. But it was still early days. By the time we got to the second album we had the benefit of having played together. In fact, some of the second album was done in England and the rest of it was done on the road.

It’s difficult to believe that Led Zeppelin II was done on the hop.

Well, it sort of was and it wasn’t. We were in LA and Mirasound studios was still there and to my ears there wasn’t too much wrong with the recordings they produced for Del-Fi records [an influential label from the early 60s whose roster included Richie Valens and Bobby Fuller].

I didn’t realise how good it was until we got in there and that’s where we recorded The Lemon Song and Moby Dick. We did Bring It On Home at the Atlantic studios. Anyway, without going into to each location with great detail, the fact was that we did bits here and there, all over the place. The final mixes were done in New York.

Is it true that you would have liked to have recorded at Sun Studios?

Oh yeah, I would have liked to have recorded there when I was 13 years old! But by the time we were recording II, it wasn’t the original Sun Studios.

The production work on II was astonishing: most noticeably on Whole Lotta Love.

Curiously enough that was the first song we did and it was recorded in London at Olympic studios. Whole Lotta Love definitely captures the attitude and swagger of the band at the time.

And then came Led Zeppelin III.

By the third album we had been touring and we had our foot in the door of America. Because it’s such a massive continent, between the first and the third album we spent a lot of time over there. So by the time we got to the third album we were having our first proper lengthy break. We couldn’t spend any more time in America, because in those days there was the threat of getting drafted into the Vietnam war if you stayed over six months, so we thought it would be better to go home and do an album.

It seemed to confuse the critics and received mixed reviews – how did you feel about that?

Well, what was it that confused the critics? I mean, it’s got Immigrant Song on it, that’s a classic rock riff track. It’s got Since I’ve Been Loving You. It’s got some really strong material on it. People really didn’t fully understand what a kaleidoscopic talent there was within Led Zeppelin. So they had already made up their minds after the first album and second album what we were about. And with the third album they were saying: “Where’s Whole Lotta Love?” and we weren’t doing format, nor should we have done.

The thing is that you could tell what was working from the response of the audiences. In those days Led Zeppelin was travelling word of mouth, by people’s ears, not by reviewers’ copy. As I’ve said in the past, I’ll give it the benefit of doubt and say that maybe that the reviewers only had a short amount of time to review the album, because it totally went over their heads. Nobody else at the time was moving with that kind of rapidity, if you like – many bands were happy to stick to a formula.

Also there were definite hatchet jobs. The Rolling Stone review [paywalled link] was a definite hatchet job, we were told that. But it didn’t matter because we had a bigger circulation than Rolling Stone [laughs]. The fact is that we were pretty well established after the first two records, so if there’s someone who’s into the band and the music they’re just going to get the product as it comes out and then they’re going to take it home and absorb it. It was unquestionably good music and as long as you believe in it yourself or yourselves, collectively, that’s what matters.

The last album In Through The Out Door is the one that seems to have received the most criticism.

Well, I’m not going to add to it. That’s my answer to that. I don’t want to add any more fuel to any fires.

When Zeppelin ended did you feel any immediate pressure to produce music?

The first thing that came along was the soundtrack for Death Wish [II], which was great because I really got into the process of writing for film – the syncopation of it and the mood of it. And I wrote it in the studio, I didn’t go in there with anything. It was fascinating. I learnt a lot doing that – I learnt a lot about myself. I surprised myself with what I could actually do under those sort of circumstances.

Would you to do something like that again?

Probably not. But I did enjoy it. It came to me at the right time, because obviously one was really shattered having lost John [Bonham], a real dear friend and the most incredible musician. So it was really good because it was something that kept me foccussed, creating 45 minutes of music for a 90-minute film. The only thing that was a bit of a shock was when I’d finished I was told that I was supposed to do an album for it as well. I had no idea that there was supposed to be an album, which was interesting.

With The Firm and Coverdale/Page did you feel any pressure to create something as monumental as Zeppelin?

No, the collaboration with Paul [Rodgers] was an offshoot from the ARMS tour. Originally Steve Winwood sang in London and then there was a proposal asking if we would like to take it to America. And Steve didn’t want to go to the States. Joe Cocker went instead and I asked Paul would he like to come along as well and he said yes. And that’s when we started getting some material together.

Midnight Moonlight was one of the songs that came out of that. And you don’t go out playing something like that unless you have real confidence about yourself. Paul’s whole application to the lyrics and the melodies was fantastic and I really enjoyed working with him – what a vocalist. And when the ARMS thing finished I said: “What about it? Let’s go do something else.” Which is how The Firm came about.

And then there was your solo album, Outrider.

Yeah. Y’know, I thought it was time to do a solo album. It gave me a chance to go out on tour and just play all the music that I enjoyed. So I went out and did some Yardbirds material, some blues, some Zeppelin, some stuff from Outrider, The Firm and the Death Wish soundtrack. I really enjoyed doing that – it was fun.

And then I did the Coverdale/Page thing and I really enjoyed that too. Actually, to be honest, I will only really do something if I really enjoy it. I enjoyed working with David Coverdale: he was really together and professional to work with. I think we did some really good material with Coverdale/Page.

It seems you’ve done pretty much what you’ve wanted since leaving Zeppelin.

Well, I have. I’ve been really lucky to have worked with some fine vocalists. I mean, the best. What draws you to a vocalist? Singers that can deliver a vocal performance and have the range and confidence to deliver. Because that’s what they would and should expect from a guitarist.

In the past you’ve praised Chris Cornell.

Yeah, I particularly like Chris Cornell’s writing. I think Black Hole Sun is an amazing piece of work.

How about your stint with the Black Crowes?

The only unfortunate thing with the Black Crowes project was that live there was a balance between their material and the Led Zeppelin stuff. And the whole set was recorded live at The Greek Theatre, but when it got to releasing an album they came unstuck because of contractual problems and could only use the Zeppelin material. This was a shame because I really enjoyed doing their songs. The Black Crowes were then and still are a fine, fine rock band.

Let’s talk about your collaboration with P. Diddy.

There was a communication that came through the office that he wanted to do a track with me and would I talk to him. So I called him up and he said that he’d been asked to do this music for Godzilla and he couldn’t get this idea of using Kashmir out of his mind because of this huge beast – he wanted something epic musically. So he really wanted to do something around Kashmir but said he didn’t want to sample it because he wanted to do something different.

So I said: “When do you want to do it?” He said Saturday, and it was already Tuesday! So I went into a studio in Wembley where they set up a link, so I could see him on a screen but I’m basically playing everything down a telephone line over the internet. It was interesting because he was in LA and there was this massive time lapse in our conversation and the audio. When we finished he said: “Right, I’m going to put an orchestra on top of this.” I was told that he ended up using two orchestras simultaneously.

When I went to New York on other business he invited me up to the studio when he had mixed it. It was absolutely epic – and he played it really loud too! Superb! And then I had a chance to play with him on Saturday Night Live and that was terrific. We did the run-through and he did something different for each performance as far as body language and his physical approach went. But his vocal timing was spot-on with every take. It was an interesting time because I was suddenly getting asked to do autographs by black people, which hadn’t happened for quite a while!

These days are you more comfortable on stage or in the recording studio?

I think it’s equal. It’s two different worlds and my approach is different to both.

What are your solo plans for the future?

At this point in time I’ve got a variety of material which I’ve written and have been working on that I hope will eventually surface. And that’s a mixture of things that have been around for a while and other things that are more current. That it’s, really. I’ve always done projects along the way as they’ve come along and enjoyed them.

Pete Makowski joined Sounds music weekly aged 15 as a messenger boy, and was soon reviewing albums and doing interviews with his favourite bands. He also wrote for Kerrang!, Soundcheck, Metal Hammer and This Is Rock, and was a press officer for Black Sabbath, Hawkwind, Motörhead, the New York Dolls and more. Sounds Editor Geoff Barton introduced Makowski to photographer Ross Halfin with the words, “You’ll be bad for each other,” creating a partnership that spanned three decades. Halfin and Makowski worked on dozens of articles for Classic Rock in the 00-10s, bringing back stories that crackled with humour and insight. Pete died in November 2021.