This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #213.

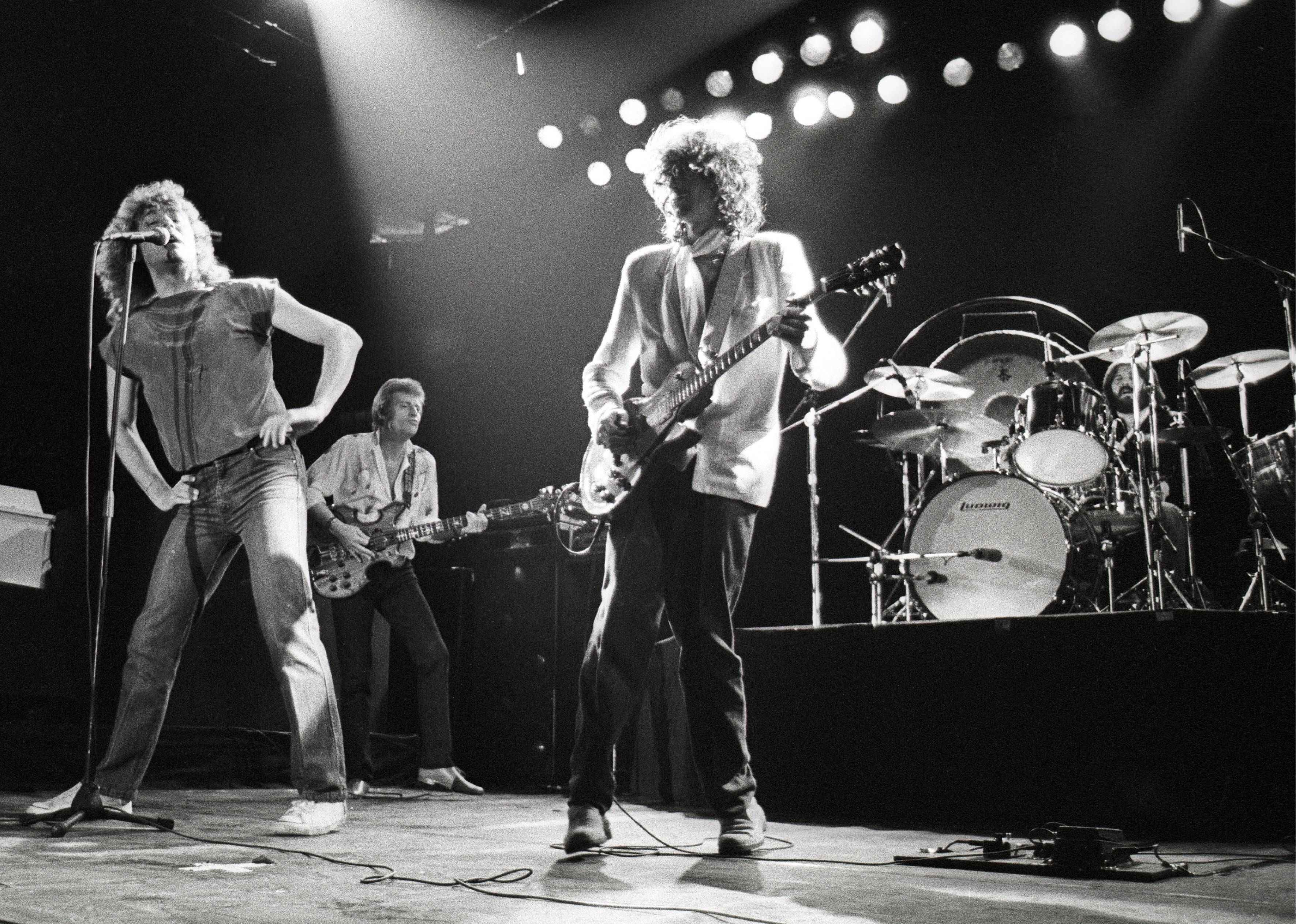

When John Bonham died on September 25, 1980, Zeppelin died with him. Two years later came Coda, an album of outtakes, including Bonham’s drum extravaganza, Bonzo’s Montreux. The deluxe version of Coda brings more buried treasure to light, such as Friends and Four Sticks (retitled Four Hands), recorded by Page and Plant with Indian musicians in 1972.

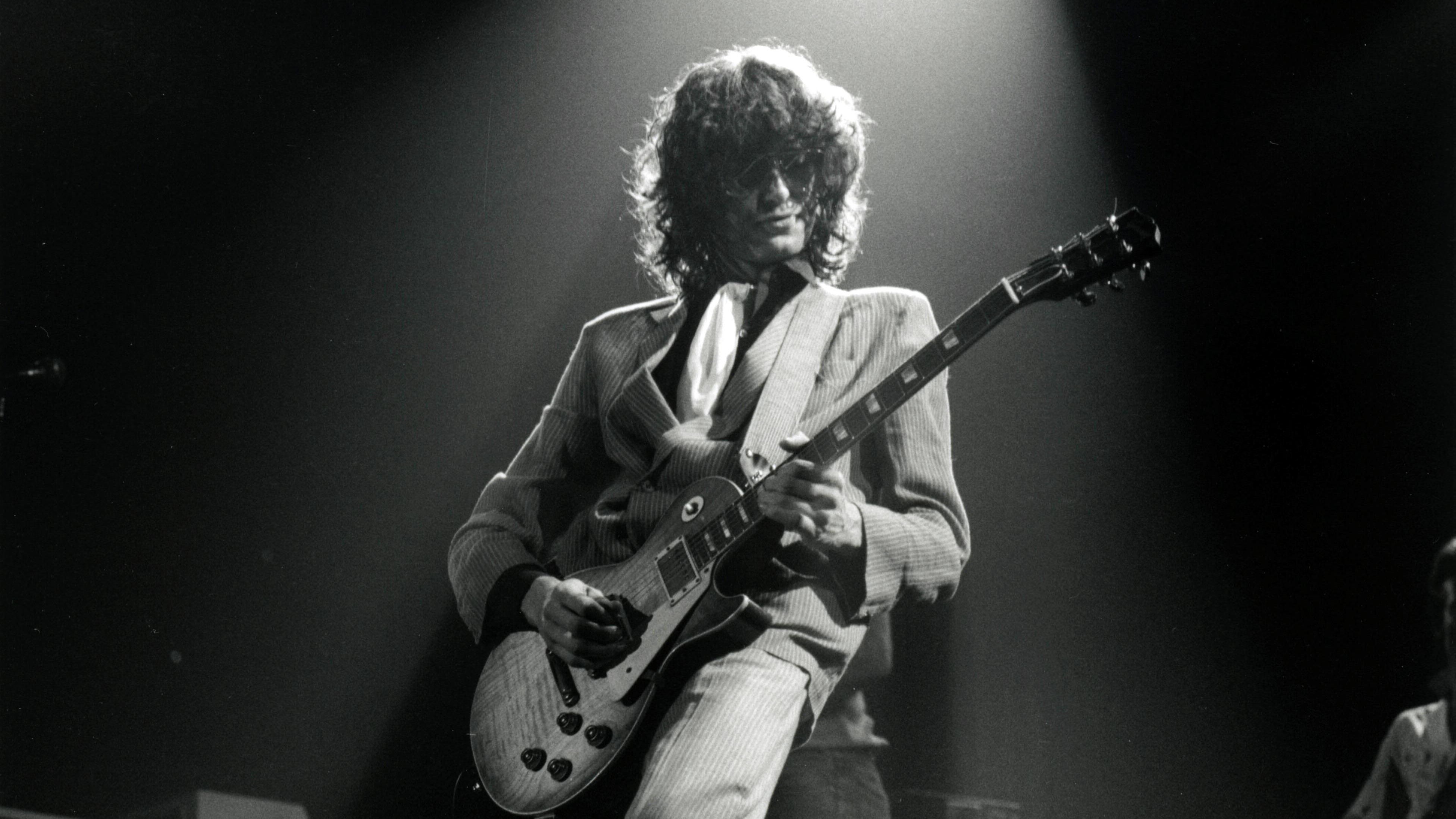

Listening to Page discussing this material, you glimpse the obsessiveness that helped make Led Zeppelin such a force, but also a reluctance to reveal too much, as if this will diminish his and/or the music’s power. You realise why Robert Plant once described his old bandmate as “a man of mystery… hiding in shadows and peeping round corners”.

Yet, you also glimpse a more innocent time – if ‘innocence’ and ‘Led Zeppelin’ could ever be used in the same sentence – before the so-called “darkness and intensity” took over. Most of all, though, you realise how much John Bonham’s death impacted on him.

Coda seemed to creep out in 1982. There was none of the fanfare that’s accompanied these latest reissues.

It was a very difficult album to approach. We’d lost John in 1980 but even when I came to do Coda, it still felt tough [long pause]. It was a contractual album. We had to do it.

How did you approach it?

It had to have credibility, because it could have been quite unpalatable otherwise. It helped that we had Darlene, Ozone Baby and Wearing And Tearing from the Polar Sessions. And only John and I knew about Bonzo’s Montreux.

Why didn’t the others know about it?

Because it was something we did together – just him and me. John was alone in Montreux at the time [Bonham was taking a tax year out of the UK in 1976], so I went there to cheer him up. John liked all those old Sandy Nelson records, because of the drums. So we wanted to make something that sounded like a drum orchestra. It was fun, but it wouldn’t have fitted on any of the albums.

So what were you aiming for with the new Coda?

To make the mother of all Codas! [Laughs] Before I started this whole campaign, I had to know what I was saving for this one – all the little treasures.

- Bonham, Grohl & Led Zeppelin’s legacy: An epic Jimmy Page interview

- Watch Robert Plant perform Led Zeppelin's Whole Lotta Love

- High Flyers - Them Crooked Vultures: 'The Best F**king Band I’ve Ever Been In!'

- Rock Icons: John Bonham by Chad Smith

Let’s talk about Friends and Four Hands, then. We’ve read about the trip you and Robert took to India in ’72, but never heard the music you made there.

We were on the plane from Australia and had to break up the journey for refuelling. I had worked out a situation where we could go into a studio [EMI Studios in Bombay] with some Indian classically trained musicians. I wanted to see if it was possible to go in with a guitar and an interpreter and make something happen.

Had these musicians heard any of Led Zeppelin’s music before?

No. It was 1972 and they were immersed in their own world. But Friends was written around the idea of Indian music. I just about managed to explain it to them. On Four Sticks, they did things in odd times and multiple beats. As far as I was concerned, I was in paradise. I’d gone in to do something that seemed impossible and I’d done it.

You were an early fan of Indian music. You owned a sitar when you were a teenager, didn’t you?

Yes [long pause]. This story has leaked out… Now I suppose it will leak out even more. I managed to acquire a sitar, when I was a teenager, early on in my session musician days. I’m not saying I was the only person interested in Indian music, and I’m not detracting from George Harrison’s sitar work but I was in there earlier… Although I had to get Ravi Shankar to show me how to tune it.

How did that happen?

I had a connection with a lady that knew Ravi Shankar and said she’d get me an introduction. I went to see him when he played in London. There were members of the Indian high commission and Indian actors there, but no other young people. I was granted an audience with the master and he showed me how do it.

Will we ever hear Jimmy Page playing sitar?

I still have the sitar and I still play, but you don’t mess with two thousand years of culture. To hear Ravi playing, now that’s amazing. It’s a spiritual discipline.

This reissues campaign had been your life for the past couple of years – but only yours. Why aren’t Robert Plant and John Paul Jones sitting here as well?

I’ve not heard from them about this new stuff, but they know how things have shaped up. But we all know I formed the band and I was the producer, and consequently I have all the points of reference, more than anyone else. [Long pause] Some people might have forgotten all the things we did, but I didn’t forget. I’m the one who knew.