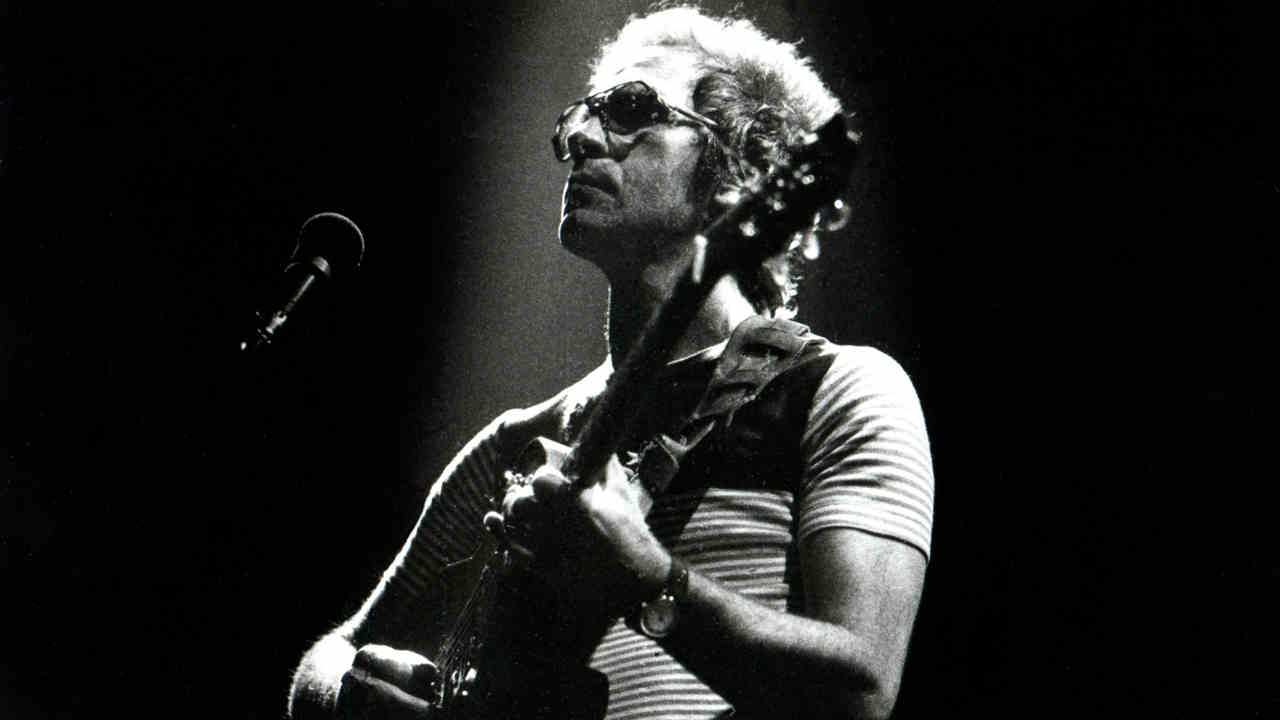

JJ Cale was one of American music’s best-kept secret. The singer and guitarist notched up a few hits of his own, including 1971’s Crazy Mama and the following year’s After Midnight, but his relatively low-profile was in inverse proportion to the influence he had – the likes of Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler have called him a huge inspiration. Cale died in 2013, but Classic Rock say down with him four years earlier, around the time of 2009’s Roll On album, to look back on a quietly influential career.

John Cale is sitting in the kitchen of his rural ranch-style bungalow with the blinds drawn against the sun, staring at the wall. He lives in Southern California, in San Diego County, outside of Escondido – which is Spanish for ‘hidden’, and that’s just the way he likes it; nice and quiet, as befits the undisputed king of minimal southern rock, the epitome of laid-back, but a sonic architect just the same. His old Airstream motor home parked out front may be re-commissioned: Cale about to go back on the road to promote new album, Roll On. Ever since his companion, an English Springer called Buddy, passed on, Cale has been on his lonesome.

“Life without an animal is terrible,” he sighs. “I loved that old dawg. And Foley before him. Keep meaning to get me a new one.” His nearest neighbours are three acres away – unless you count his close friends, the squirrels, racoons, rabbits and birds running round his modest estate. “It’s like a Disney cartoon out here,” he chuckles.

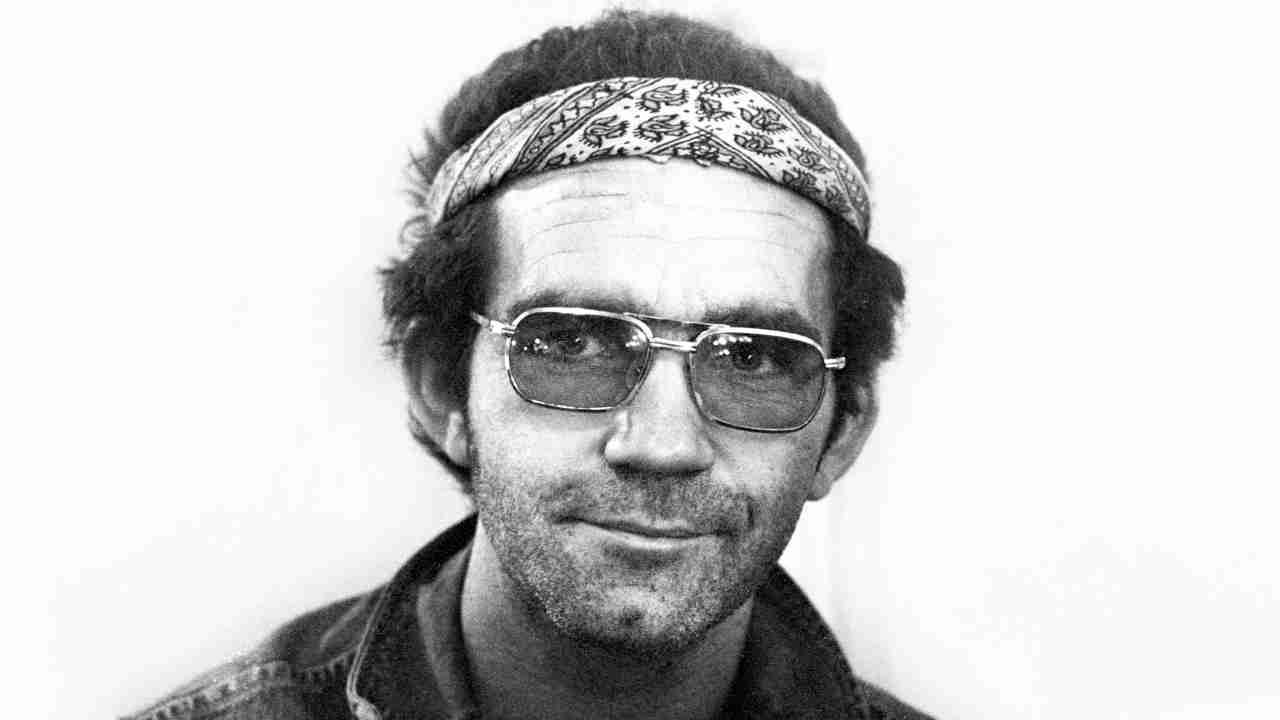

The 70-year old Oklahoman, or Okie, with a long drawl is weather-beaten, with a grey beard, looking not so much unshaven as unshaveable. Dressed in ancient Lee jeans and a work shirt, and pulling on a Kool, Cale admits to being a hypochondriac. “I’m gettin’ by okay for an old man, though since the rain came and ended the drought I got flu. Still alive though. At my age that’s a good deal,” he chuckles. “Any day above ground…”

Forever typecast as a recluse, Roll On is ol’ JJ’s sixteenth record. And it’s terrific, on a par with his early 70s albums – Naturally, Really and Okie – which turned him from a 32-year-old late developer into an American legend, albeit of the best-kept secret kind. It’s safe to say that without his influence Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler would not be where they are today, while Neil Young says: “When I think of great guitarists I think of Jimi Hendrix and JJ Cale. There is no one better than him.”

Clapton’s cover of Cale’s After Midnight on the former’s 1970 debut solo album gave his mentor a weird career, though he still reckons “my songs are way more famous than I am. My bass playing friend, the late Carl Radle, played him [Clapton] the tune.” When he later heard that Clapton had covered it, he thought it was a wind-up. “Then Delaney Bramlett [of Delaney And Bonnie] talked me up. That was like discovering oil in your backyard. But I just do it and move on. Hell, I can’t tell one of my albums from the next. I try not to make ’em sound like anything else, but everything I do sounds like me. It is what it is.”

Roll On features Clapton on the title track, a song that Cale has been playing live for more than 20 years. The two men have combined before, for the The Road To Escondido album [2006], a mutual admiration project which won Cale his one and only Grammy – much to Clapton’s delight and embarrassment.

“Originally I asked him if he’d consider making an album with me,” Clapton recalls. “ I really wanted him to produce me, because I’m a fan of his recorded sound. His minimalism is the way I want to go. He has a unique approach, and I wanted to avail myself of that.

“So I moved in with him for a week, to go over material and to get to know each other. Not a lot of work got done, but that wasn’t the point. His idea was to bring in the musicians and record ‘live’. I thought we might have a problem capturing the ‘groove’ I heard on his demos, usually created with drum machines etc and such an important part of his sound. Eventually the Road… album became a duet thing, which improved it and made the experience more memorable for me.

“Hanging out with John is one of my favourite pastimes. He’s got a great sense of humour, and has been misunderstood by most people, referring to him as a recluse when he’s very sociable, open and charismatic. He just prefers his own company. JJ has never even been nominated for the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, while I’ve been inducted three times. In my opinion he’s one of the most important artists in the history of rock, representing the greatest asset his country has ever had. Yet a lot of people have never even heard of him.”

Clapton’s involvement changed that to an extent, although the Grammy didn’t faze Cale.

“That is still in the box,” he says. “I may put it on the mantle but I probably won’t. My domestic duties are kinda slow. It didn’t really change my life, ’cept it was a nice pat on the back. Good for my ego. Me and Eric laughed about it, but I have to thank him for boosting my bank balance by recording After Midnight on his first solo record, then cutting Cocaine and I’ll Make Love To You Anytime. Same with Lynyrd Skynyrd, who cut They Call Me The Breeze. Man, they rocked that up! They cut it so hard it astonished me! I wasn’t aware they were even listening to me. Then those kids all died. That was too bad.”

Cale hasn’t had a hit himself since 1972, when a Little Rock DJ flipped his Magnolia single and hammered the B-side, Crazy Mama, which eventually reached No.22 on the Billboard chart. Top Nashville guitarist Mac Gayden, of Area Code 615/Barefoot Jerry fame, who played the distinctive wah-wah slide on that track, recalls the session: “Cale’s producer, Audie Ashworth, hired me for the studio at Bradley’s Barn, outside Nashville. We ran through it one time only, then Cale gets on the talkback and says: ‘Come on in, Mac, and sign the time card, you’re done.’ I said: ‘I can do it better.’ He said: ‘No, you can’t.’ I swear it only took seven minutes – first take.

“That cut launched the career of one of America’s most emulated guitarists. John was a total joy, very loosey-goosey with a don’t-sweat-the-small-stuff vibe. In a business packed with people trying to be hip and cool, he is a rare personality.”

Shortly afterwards, Gayden joined Cale’s band for a tour supporting Black Oak Arkansas, whose teenage audience started throwing bottles and booing them in Baton Rouge, LA. “So we turned our amps to full throttle and let rip – and it worked. Next night we played the Warehouse in New Orleans with Quicksilver Messenger Service. JJ still played on a stool with his back on the crowd, but they got it.”

Gayden also witnessed a rare flash of Cale temper. “The last time I saw John was in LA a few years ago, at his house. We talked about ‘old friends’, and then suddenly John started to ‘rag’ on Mark Knopfler. He mentioned how much he didn’t appreciate him ripping off his guitar style and his singing. Just as John was reaching a fever pitch, guess who calls? None other than Mark Knopfler himself, inviting JJ to go on the road and open for his upcoming tour. John was nice, but hung up and started to ‘rag’ him again. I left in total agreement. A few weeks later I read that he was opening for Mark on his US tour. I guess imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.”

Cale – who Clapton calls “a superior musician… one of the masters” – runs in a straight line. In the late 50s and early 60s he cut a sequence of rockabilly and rock’n’roll sides with his own Quintette and helped create the Tulsa Sound with fellow Oklahomans David Gates and Leon Russell. In 1965 he moved to Los Angeles when pop producer Snuff Garrett told him that psychedelia was a-happening. Cale migrated and hung out with members of Ronnie Hawkins And The Hawks (the nascent Band), before making the one-off album A Trip Down The Sunset Strip in 1967 with old Okie pals he christened The Leathercoated Minds.

The LP contained super-fast acid takes on the Yardbirds’ Over Under Sideways Down, the Byrds’ Eight Miles High, Donovan’s Sunshine Superman, and a few originals composed under the influence of LSD and plenty of pot. “I hate that album,” Cale says. “I’ve tried to burn it whenever I see one. We bought into the psychedelic scene but it was a bad imitation. You guys might like it, but you’re nuts! I enjoyed LA though. I played at all the East LA bars. We supported Johnny Rivers when he was hot, and I saw Love and The Doors. I also saw Otis Redding, who was better. I think I was only the third act ever to perform at the Whisky. Club owner Elmer Valentine gave me the JJ handle. Said it would look good on the marquee. Smartest thing I ever did.”

While the hierarchy of young, long-haired LA groups thrived, Cale found he’d outworn his welcome. He had a spell as an engineer, working on Blue Cheer’s debut album, Vincebus Eruptum, but felt out of place among the acid crowd. “I spent too much time drinking and got real poor, real fast,” he recalls. “LA ain’t a good place to be hungry. So I came home and got a job in a country band and lived in motels, earning 10 bucks a night and all the beer you wanted. I really thought I was finished and would end up selling shoes, until Eric cut After Midnight. I was going to be a construction worker, or an insurance man. I was that down on luck.”

One day, Audie Ashworth, Cale’s future business partner, told him that Clapton had covered his song. He didn’t believe it until the first royalty cheque hit the mat. “Audie got me to Nashville around 1971 and we made Naturally for $3,000-$4,000. This is when the south was gonna rise again, like Charlie Daniels sang. Nashville, Muscle Shoals, Alabama, Memphis – suddenly they became hip towns. The players were real good and people like Bob Dylan and Steve Miller were recording in our neck of the woods. It was good timing because rock folks discovered country. The studios were good and professional and the guitarists could play a lick. Like the Lovin’ Spoonful song [Nashville Cats] says about the 1,352 pickers in Nashville.”

The stoned, sexy calm of Cale’s albums gave him instant cult status among discerning record buyers. “Yeah, but I didn’t put Nashville on the map. Perhaps to Europeans I helped, but the Grand Ole Opry was famous since the 40s. My heroes remained the same: Charlie Parker, Elvis ’fore he got too operatic, Chuck Berry, Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown and Mose Allison. I loved The Beatles’ Rubber Soul and that song We Can Work It Out. I loved Dylan’s folk stuff, Randy Newman, Nilsson. I don’t mind stealing a lick or borrowing a technique off them. I’m a musician, that’s what we do.”

Naturally was an easy album to make for Cale, since he had hundreds of unrecorded songs in his locker. The albums Really and Okie followed in short order, the former written on the way to Shelter Studios and finished in six days. “Audie and the label owners, Leon Russell and Denny Cordell, phoned every six months: ‘When’s the next one ready?’ My attitude was always: ‘What was wrong with the last one?’ But I got sucked in.”

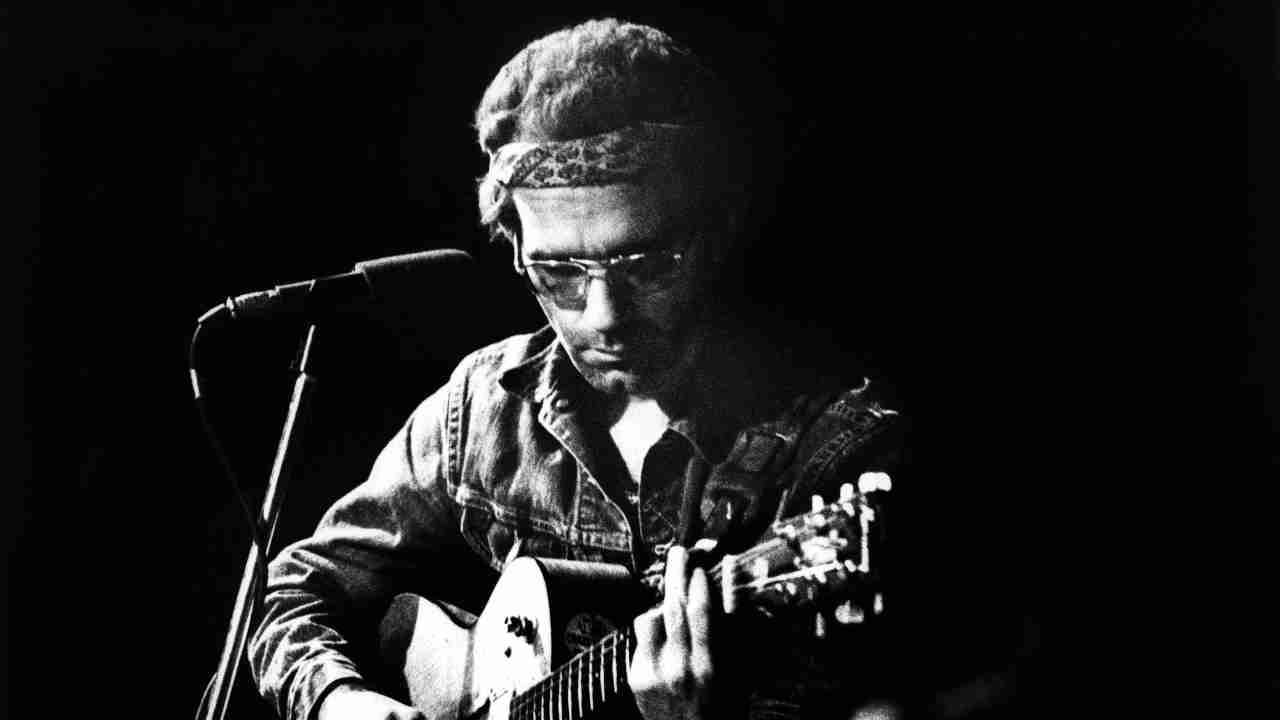

In 1976 Cale embarked on his first of two European jaunts, promoting his most successful album, Troubadour. I saw him play at Hammersmith Odeon. It’s an indelible, dope-crazed memory. “I don’t remember it myself,” Cale laughs. “It was a blur of VW vans and big cities. The fish and chips were good in London. Eric sat in with us, unannounced. I’ve spoken to people who didn’t know he played! “Am I laid back? I guess. I call my music ‘humming mud’, and my singing, if you can call it singing, is craggy and baggy. My range is kinda limited. One and a half notes – on a good day.”

Troubadour included the candid drug song Cocaine, while in Cale’s touring band was guitarist Christine Lakeland, who many have taken to be JJ’s muse. It’s thought that Cale has never married, but may have several ‘wives’. “Hmm… I don’t mind a bit of innuendo and sensuality but I don’t discuss my private life,” he says. He once filled out a Guardian newspaper questionnaire and omitted to answer anything remotely personal other than ‘What vehicle do you own?’ (truck and motor home), ‘Object always carried’ (pocket knife), ‘Motto’ (do unto others before they do unto you) and ‘How would you like to die?’ (a very old man). ‘Significant others’ didn’t use up any ink from his pen.

“Nobody likes to be followed to the bedroom. Well, maybe some people do,” he smiles. “Christine is a very old friend. She’s way more of a recluse than I am.” It’s true. Lakeland’s website contains one page: a photograph of her holding an electric guitar. Marvellous.

The thing about JJ Cale is that he doesn’t change and doesn’t need to. He was good when he started and he’s good now. Like his song says: ‘They call me the breeze/I keep blowing down the road.’ He ain’t broke, he don’t need fixing. “I’ve always been rock’n’roll and country; then again I’m more jazz than your average Britney Spears. But I ain’t a hermit. I’m home a lot writing songs cos that’s what I am. You don’t get that done by playing basketball…”

Five years ago Cale returned to his roots when he recorded the album To Tulsa And Back, hooking up with his old cronies Lakeland, Bill Boatman and Jimmy Karstein, and resolving his fall-out with Ashworth, who became exasperated every time Cale told him: “Send me the money and let the younger guys have the fame.” It was going to be called To Nashville And Back, but Ashworth died before the tapes were loaded.

New album Roll On closes with a song called Bring Down The Curtain, which says: ‘Enough is enough/Can’t do it no more.’ Is that it? Adios, amigos? “I don’t know. I wouldn’t have put that on but it is a good ending. Didn’t mean to depress ya. I’m at an age where I am looking at the end of the clock. Intimations of mortality? I guess. Mind, Willie Nelson is older an’ me and he’s still going. So don’t take it too literally. I’m not only a reality writer, I’m a fictitious writer. I like to amaze myself with a cute twist and turn.”

Perhaps that’s the ultimate self-analysis from an artist who doesn’t do ‘projects’ and only signs one-off deals. “I don’t ever think I’m making a record,” Cale says. “I just do it, and when it falls into place, 75 per cent cohesive, I’m always surprised. I listen to it and think: ‘Is it any good?’ ‘Are the songs any good?’ ‘Is it a concept?’ I don’t have a clue. It’s just natural evolution. Everything I do is an accident. But it’s my accident.”

And, he points out. “No one tells me what to do. There’s no one at my door. I’m famous for Cocaine, Call Me The Breeze and, hell, they might even make After Midnight the Oklahoma State Song soon. It don’t bug me if that’s all the average guy knows. I don’t make music most young people would like. Some do. I isn’t no rapper, though I like rap now they made the lyrics more interesting.”

Suddenly Cale gets a fax confirming the bitter-sweet news that he’s booked to tour California and beyond. “Oh Lord,” he sighs. “I’d better watch my voice. I’ve got to play well enough so people don’t throw tomatoes at me. If I’m healthy enough I might even get on an aeroplane and see you. Maybe.”

Originally published in Classic Rock 132