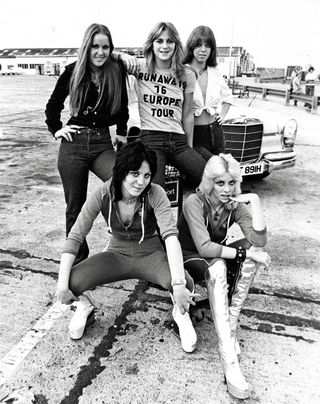

“There’s nothing more threatening than a girl with a guitar,” Joan Jett famously said back in 1999.

More than 20 years later she hasn’t changed her stance. She has never been afraid to speak her mind or show the world exactly how she earned that bad reputation she sings about. “The only reason I have a bad reputation is because I’m a girl and dare to do these things that boys do,” Jett huffs.

In fact, if she had a motto it would probably be ‘Make me’. From the off, Joan Jett has been full of bold impudence and rock action, provocatively straddling her guitar between her legs while channelling her beloved rock gods of yore, Marc Bolan or Keith Richards, and has spent the past four decades showing the world that she can rock as hard as the guys, if not harder.

But Jett’s aim wasn’t to even the score in the war between the sexes. She had bigger goals. “Well, I do,” she says, stretching out the last word. “But if anyone ever said anything against girls playing rock’n’roll, I was ready to go to war.”

And she did.

“One time, The Runaways opened for Rush, I think in Detroit,” she recalls. “I remember those guys standing at the side of the stage laughing at us. And, you know, if I was Rush I wouldn’t be laughing at me. Then there was Molly Hatchet. The guys said: ‘I can’t believe we’re opening for a bitch.’ And then Scorpions were mad because they were a German band and we were bigger in Germany than they were. People just don’t want to see girls doing things they don’t think girls should do.”

But that has never stopped her.

Over the years she’s written songs full of piss and bravado, such as the Bad Reputation and the tongue-in-cheek Black Leather, a song that doesn’t extol the virtues of her favourite stagewear so much as emphasise that she’s going to do what she wants to: ‘Black leather, I wear it on stage/Black leather, I’m gonna wear it to my grave/Black leather, I will wear it anywhere/Because my name is Joan Jett and I don’t care.’

But the thing is, she does care.

“I think what’s always kept me going is the belief that rock’n’roll could change your life. Not making it more than it is, but a song can just hit you at a certain time. Something that gives you the courage and energy to continue following your dream.”

Just as David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust album did for her: “The whole record was about someone trying to aspire to be a star, and I could relate to a lot of the lyrics.”

By now, Jett has reached near-messianic status. Former world heavyweight boxing champion Mike Tyson considered her his lucky charm, and ritualistically phoned her before his bouts. Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong considers her a role model, and covered Jett’s Don’t Abuse Me. Celebrated punk artist Shepard Fairey released a limited-edition print of Jett reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s canvases. Jett is about to launch a clothing line with Todd Oldham, and is producing an album for rockabilly icon Wanda Jackson. A documentary about Jett, directed by Kevin Kerslake, lauded for the tragic As I AM: The Life And Times Of DJ AM, is nearing release. If anything, the Joan Jett myth has grown.

Over the past few years she has written songs with Dave Grohl and Against Me!’s Laura Jane Grace, while Pearl Jam guitarist Mike McCready posted a snapshot of him and Jett posing backstage in Seattle with goofy grins on their faces. Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan is slavish in his devotion to her.

Jett is not just a female role model and style influence (although she certainly is that, complete with her own Barbie doll, and Pinterest pages devoted to her eyeliner, shoes and humanistic politics), but also a signifier. She exemplifies what it means to be single-minded about what you’re put on this earth to do, and then do it without compromise but with decency and grace.

In 2008, Norwegian all-girl pop band The Launderettes released a song called What Would Joan Jett Do?. The slogan turned up on T-shirts, famously worn by, for one, Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna, and on bumper stickers as the acronym WWJJD with Jett’s face, indicating that the former Runaway had become a touchstone for a kind of integrity that a new generation could measure up to.

Over the years, Jett has acted as spiritual advisor to Ian MacKaye, Paul Westerberg and Peaches. She’s been called the Godmother Of Punk, the original Riot Grrrl and the Queen Of Noise (after the second Runaways album, Queens Of Noise). “It’s nice that people have that sort of impression of me. But I simplify it so much more: I say I’m just a rock’n’roller. I can’t say I was the first woman to do it. But I’d like to be remembered as one of the first women to really play hard rock’n’roll and mean it.”

In her 2015 acceptance speech for the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, she said that rock’n’roll is “an idea and an ideal… rock’n’roll means more than music, more than fashion, more than a good pose. It’s the language of a subculture that’s made eternal teenagers out of all who follow it. It’s a subculture of integrity, rebellion, frustration, alienation – and the glue that set generations free of unnatural suppression. Rock’n’roll is political. It’s a meaningful way to express dissent, stir up revolution and fight for human rights.”

The politics didn’t come until later. At first, she was just a teenager pursuing a dream.

It’s easy to say that if Joan Jett didn’t exist we’d have to invent her. But no one had to. She invented herself.

By the age of 13 she’d already seen Black Sabbath live. But if you needed a place to start, you could blame the New York Dolls for Jett’s career. Barely a teen, she witnessed the trashy, in-your-face art provocateurs at a club near her suburban Maryland home. Never mind that she was underage. History would prove that she wasn’t going to let a little thing like age stop her – then or now.

“I was in the front row and stole David Johansen’s empty beer bottle after the show,” she recalls. “It was my first rock’n’roll souvenir.”

It’s safe to say she took more than just the beer bottle from the Dolls. Their raw, untutored musical approach showed her that anything was possible if you just had the right (bad) attitude.

Less than a year after that Dolls show, the serious, intense teenager was deposited without ceremony into the suburbs of Southern California just before her fourteenth birthday.

Other, less well-adjusted teenagers might have felt a sense of dislocation moving west, but not Jett. It nudged her one step closer to her dreams. She was only 25 miles and a couple of bus rides from the nightclub Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco on Sunset Boulevard. It was ground zero for the glam movement in the US, and Jett knew it held a mysterious key.

“Once I got to LA I had an idea that I wanted to be in a rock’n’roll band,” she explains. “An all-girl band, serious about playing. I read about this place in Hollywood that catered to teenagers, playing British music that never made its way over here.”

It turned out that Rodney’s was the perfect laboratory for Jett. It had danger, the whiff of rock-star decadence, but most of all there was a group identification through music, in that razor-thin chasm that existed between glam and punk. “A defining moment for any teen misfit is finding others like yourself, even if the only thing you share is the feeling of not belonging anywhere else,” Jett reminisces.

She put on her own version of glam finery, stood in line for (and got) Keith Moon’s autograph, and once encountered a dead body on her way to the club. She knew she was where she needed to be – corpses notwithstanding.

“Everyone was dressed up with huge platform shoes and glitter. The boys wore make-up. Everyone was flamboyant and everything was androgynous. That’s where I was turned on to a lot of Bowie, T. Rex, Sweet, Slade and Gary Glitter.”

It was also the first place she heard Suzi Quatro. “When I heard 48 Crash I thought to myself: ‘Well, here’s a girl playing rock’n’roll.’ If Suzi Quatro could do it, I could, and there had to be other girls too.”

Which had everything to do with why Jett parked herself in the lobby of West Hollywood’s Continental Hyatt House to catch a glimpse of Quatro in March 1975. She sat there the entire day, with a friend, not approaching Quatro, just staring when the singer walked by. “What’s with the girl who keeps looking at me and looks just like me?” Quatro asked her then-publicist/tour manager, Toby Mamis.

Mamis finally approached Jett at 11pm and explained that Suzi had gone to bed. “I can’t go home,” Jett said. “The last bus back already left, and I told my mom I was staying with a friend. I’ll be okay here.” Touched, Mamis let the teen and her friend sleep on the floor of his hotel room.

Jett didn’t get to meet her idol until years later. But Mamis was to play a pivotal role in her life.

After that nervy vigil, things seemed to speed up for Jett. Within the month she met Hollywood impresario Kim Fowley through Kari Krome, a girl about her age from Rodney’s. Krome wrote songs, which Fowley was publishing. “I told Kari I thought we should form an all-girl band,” Jett recalls. “She said she didn’t play, just wrote, and maybe I should talk to Kim about it.”

She contacted Fowley, telling him she played rhythm guitar and wanted to form a female band – not a novelty act, bona fide players. Soon after, while Fowley was standing in the parking lot of the Rainbow club, a girl called Sandy West recognised the ghoulish six-foot-five songwriter, and told him she was a drummer, played in bands in Huntington Beach and wanted to form an all-girl band. He gave West Jett’s number and the drummer called her. Jett took four buses to Huntington Beach, and she and Sandy jammed.

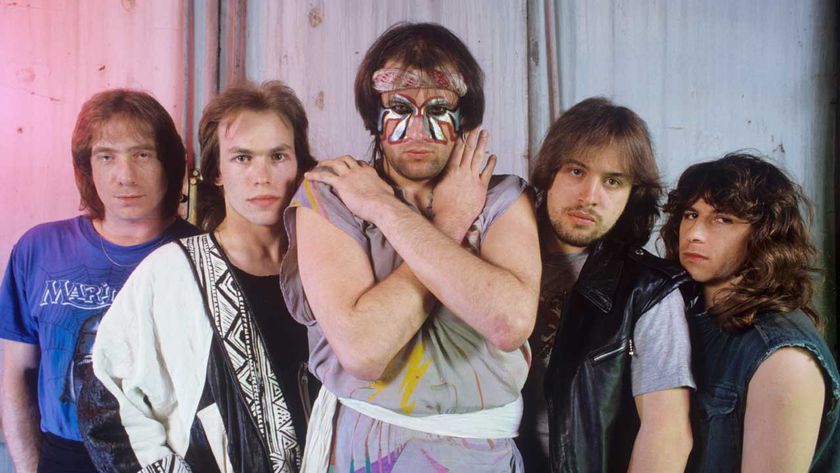

Almost immediately the two new compatriots (plus Krome) started auditioning girls, and hired bassist Micki Steele [replaced by Jackie Fox], guitarist Lita Ford and singer Cherie Currie, creating the seminal Runaways line-up. Fowley would conduct “heckler drills,” in which he and others would yell and throw things to “toughen up” the girls for the stage.

“As far as assaulting the citadel of rock’n’roll, I never dreamed I couldn’t. I thought people would freak out over an all-girl rock’n’roll band.” Jett said in 2000. “And they did.”

The Runaways released four studio albums and one live set, toured Europe and were adopted by Motörhead. They partied with Robert Plant, toured with The Ramones and opened for Tom Petty. But they were noticed more for the novelty of five kittenish teenagers than as musicians. Album sales were low in the US, but were akin to The Beatles in Japan, where girls would chase them down the street with hairbrushes, hoping to collect strands of their lacquered hair.

The Runaways broke up on New Year’s Eve 1978. “We were into different kinds of music, and it wasn’t fun any more,” Jett explains. “I was hanging out with Sid Vicious in London – we were supposed to be doing an album, but it never happened – and the other girls hung out with Thin Lizzy. Our interests were diametrically opposite; it was so clear I was into punk rock and the other girls weren’t.”

Jett refused to allow herself to be derailed by the demise of The Runaways – although she began partying and drinking to excess. “I was in bad shape,” she told interviewer Nic Harcourt in 2013.

Pulling herself out of a potential tailspin, she plotted her next step. She hired early benefactor Toby Mamis – co-manager of the last incarnation of The Runaways – as her de-facto manager, and the pair brought in former Sex Pistols Paul Cook and Steve Jones to produce and play on a demo. One of the recordings was songs was by British glam also-rans The Arrows, a B-side called I Love Rock ’N Roll that Jett had heard on British TV.

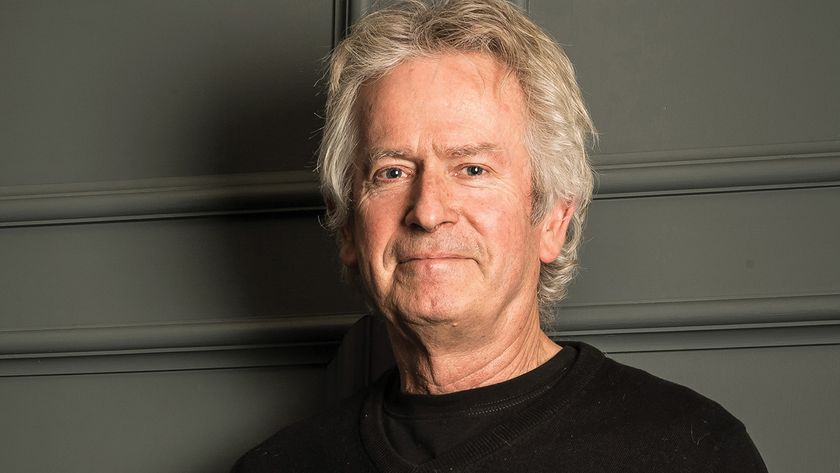

Jett returned home to finish songs for a film based on The Runaways. But when she stalled trying to come up with eight songs in six days, Mamis asked Kenny Laguna, a songwriter/producer/musician, to collaborate with her. Laguna was reluctant, but his wife, Meryl, was intrigued by Jett’s potential. Laguna signed up, and found himself promising to get Jett a record deal.

“I had no idea how hard it was to get a deal for a woman with a guitar,” Laguna recalls. “An Atlantic Records exec said: ‘Joan should stop hiding behind the guitar and get out there and rock like [Pat] Benatar.’”

But that was not on the cards. If anything, Jett subsequently made Benatar herself pause for thought: “Joan Jett made me look like Marie Osmond,” she said. “She was such a hard-ass.”

Jett relocated to Laguna’s home in Long Beach moving into the couple’s spare room. Six months later, Laguna had signed on as her manager, and moved his adjunct family to London, where Jett’s first album was recorded.

The self-titled solo debut was made before Jett put together The Blackhearts, and was released by the Ariola label in Europe in May 1980. No US label was interested – a whopping 23 of them passed. Undaunted, Laguna and Jett decided to release it on their own and formed Blackheart Records, making Jett one of the first women to own her own label. Most of their sales were from the boot of Laguna’s Cadillac after shows.

The demand for the LP grew, overwhelming Blackheart Records’ ability to keep up with the orders. In a twist of long association and kind fate, Neil Bogart, architect of Kiss’s success at Casablanca Records during the previous decade, took a chance on Jett, re-releasing her album on his newly formed Boardwalk Records label in 1981. But first he insisted she rename it Bad Reputation, after what would become Jett’s second-most famous song, thanks to a second life as the theme for the TV series Freaks And Geeks.

Now she needed a band. Her ad in the LA Weekly stated: “Joan Jett wants three good men. Show-offs need not apply.”

With the help of X’s John Doe, playing bass and acting as arbiter on hiring decisions, they found bassist Gary Ryan, a recent guest on Doe’s couch, guitarist Eric Ambel and drummer Lee Crystal.

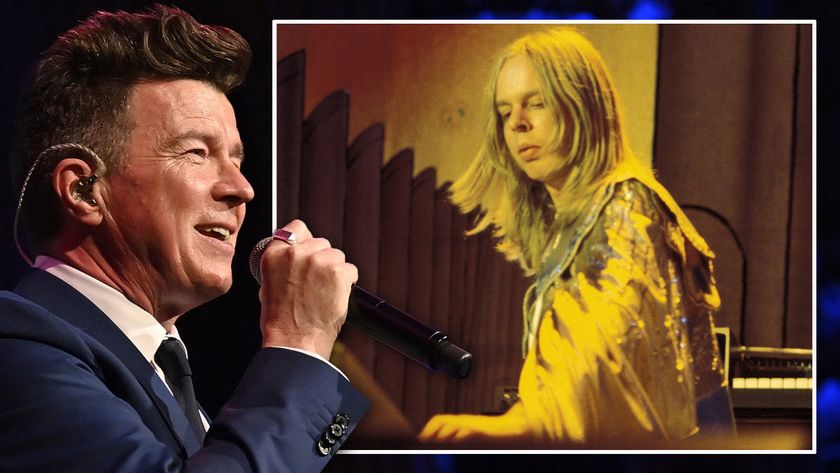

Jett and The Blackhearts toured relentlessly, recording the tracks for I Love Rock ’N Roll between dates. Once back in London, Laguna re-recorded the title track at The Who’s Ramport Studios. Released as a single, it reached No.4 in Britain in April ’82 and the top of the US Billboard chart, where it stayed for seven weeks. It became a jukebox/bar-band/karaoke classic – something Jett attributes to the intervention of Elvis Presley.

“The week after I Love Rock ’N Roll came out, we were on tour and had stopped in Memphis. Of course, we decided to visit Graceland and pay homage to Elvis. We drove to Elvis’s grave, and since I always carry guitar picks with me I laid one on his gravestone. When we got back into the van, it wouldn’t start. Elvis’s aunt came out, took pity on us and brought me back up to the house. She kept commenting how much I looked like Elvis – at the time it felt really important. The next week, we started getting the calls that I Love Rock ’N Roll was going to be a hit. I always thought maybe Elvis had something to do with that.”

Following her signature hit up the charts was Crimson And Clover, a psychedelic take on the Tommy James And The Shondells classic, but it was relentless touring – sometimes as many as 250 dates a year – that really honed her craft. Finding her comfort zone early on in that borderland between glitter and punk, Jett never worried when rock tastes shifted from punk to hair-metal to grunge to Britpop to EDM and back. She has kept on playing her stripped-down rock’n’roll, with its combustible choruses, trashy glam flourishes and hard-driving rhythms.

What she writes about now in her fifth decade is different. “I know I’m not a Runaway any more. I don’t write songs like a twenty-one-year-old any more, and I don’t want to. I have much more to say.”

Her 2013 album Unvarnished exposed vulnerability and an emotional fragility she had never shown on record before. “I think I had to express what I was feeling inside, which is what I guess we always try to do as songwriters. I called that time period the decade of death, when people I know, close to me, started dying. No matter how old you are, you think you’re twenty, and then something happens in your life. For me it was my parents dying, and I had to deal with the repercussions. It was jolting to realise that it’s time to be responsible. I’m not saying that you lose all your playfulness, but it’s definitely a wake-up call.”

During recent years she’s been taking new risks, personally and professionally, executive-producing the biopic The Runaway, producing a film called Unbeatable John (in which she also had a role) and starring in a film adaptation of Stephen King’s novel Big Driver with Maria Bello and Olympia Dukakis. She has appeared on Criminal Intent, The Muppets and Walker, Texas Ranger, and went skydiving after visiting an army base to entertain US troops overseas. She travelled to India on her own spiritual quest after reading Conversations With God, works tirelessly for animal rights organisation PETA and supports pro-choice causes.

Although she has never made an issue of gender, over the years she has inspired countless girls to form bands, and every day people will come up to her while she’s riding her bike on the boardwalk, or wandering through the small beach town she calls home, to tell her she has changed their lives.

“That’s what makes it all worth it, to know that people get it,” says Jett. “I’ve had many people tell me that my music has saved their life. That’s the ultimate compliment. I owe those fans to give it all I’ve got. I yearn for connection with the audience, to let them know we are the same, with desires, fears, trials, pain, lessons to learn. It’s just the path that’s different. But not that different."

Joan Jett joins Alanis Morrissette's Triple Moon tour in June. This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 2456, published in January 2018.