John Mayall & The Story of the Lost & Legendary Bluesbreakers Lineup

The mythologised Bluesbreakers line-up of John Mayall, Peter Green, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood never made a studio album and shattered after just three months.

Now, with the excavation of a Dutch fan’s live bootlegs, that legendary four-piece lives again. “These tapes are a piece of history,” Mayall tells The Blues. “And Peter has never played better…”

London, February 1, 1967. The Ram Jam Club is living up to its name. Amid the fug of smoke and crush of bodies, nobody notices the Dutch teenager with the oversized reel-to-reel tape recorder, as he holds up a microphone to capture the set by John Mayall’s latest Bluesbreakers line-up.

“It was so packed,” remembers Tom Huissen, “and everyone was smoking. But this was the best music I’d ever heard in my life, so to me, those clubs were heaven. The crazy thing is that, at the time, I never thought about the world impact it would have. It was only later that I realised, ‘My God, I saw the Bluesbreakers with Peter Green, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood’. To me, it was the best line-up that John Mayall ever had…”

Fast-forward to the late summer of 2014, and a breakfast meeting in the San Fernando Valley, California, between John Mayall and his producer Eric Corne. The business at hand was Mayall’s next studio album – due out later this year – but the octogenarian bandleader had something up his sleeve. Almost half a century after Huissen trailed and taped Mayall’s Bluesbreakers at five clubs across London, the Dutchman and bandleader had struck a deal on the bootlegs, so setting in motion the release of last month’s Live In 1967.

“We went out for breakfast at some greasy spoon in the Valley,” Corne tells The Blues. “That’s when John surprised me and said, ‘Hey, I’ve got these old tapes with the Fleetwood Mac guys, and do you want to work on them?’ I think he just found it exhilarating, because he’s so proud of that band. And I was, like, ‘Oh my God’. Because there’s just a mythology about that line-up – and it’s great that this album proves they live up to the hype.”

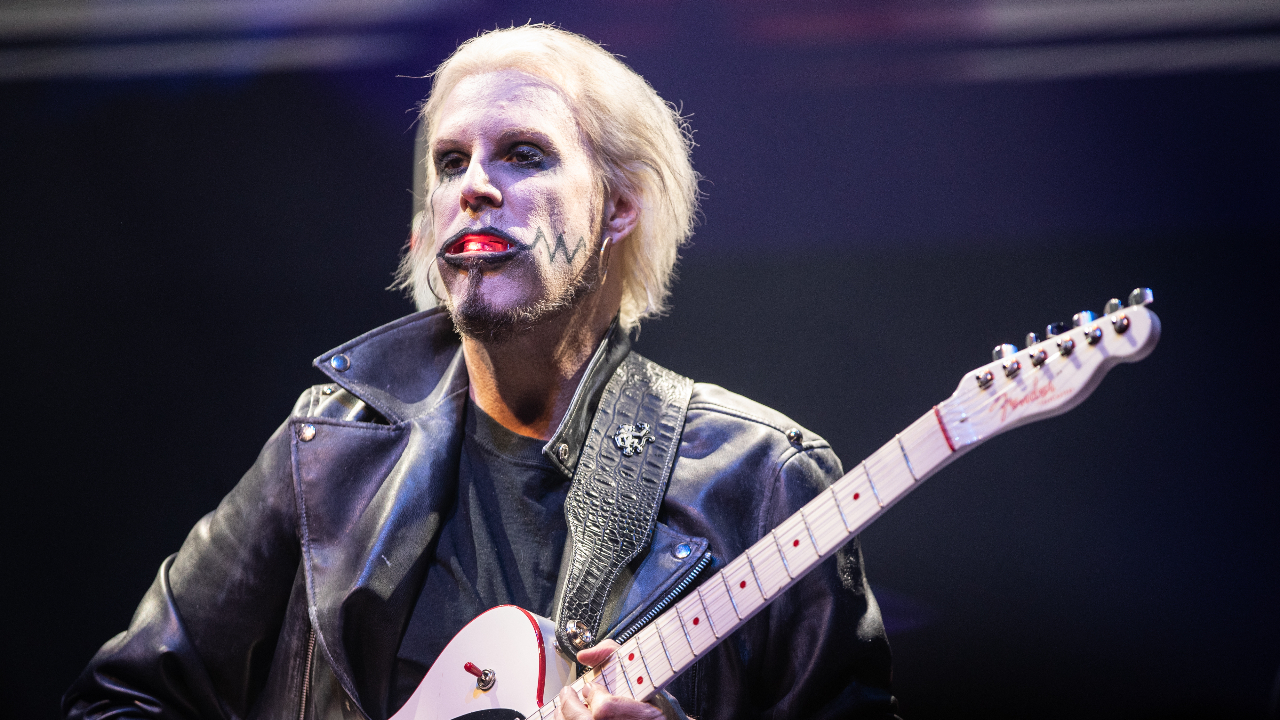

Above: Peter Green cementing his legend at Manor House [photo: John Slade].

Forget about Clapton and 1966’s ‘Beano’ album. For Bluesbreakers connoisseurs, the most exciting period began when the Surrey wonderboy split for Cream, and his one-time understudy Peter Green stepped formally into the breach. “Does Peter’s playing deserve the hype?” muses Mayall, of that drop-to-your-knees touch. “Oh, very much so. People talk about those three guitar players – Eric, Peter and Mick Taylor. They were all very special, and they don’t sound like anybody else. But I think there’s been a lot heard of Mick and Eric, of course, but perhaps a lot less of Peter in his heyday.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Previously, Green’s run in the Bluesbreakers was best represented by 1967’s studio album, A Hard Road (on which Mayall and McVie also play). Now, with the excavation of Huissen’s tapes, there’s suddenly a case that the guitarist found his ultimate platform after drummer Aynsley Dunbar was replaced by the gangling figure of Mick Fleetwood. “Peter didn’t get along too much with Aynsley Dunbar’s style of playing,” reflects Mayall, “even though A Hard Road is a great testament of how that band sounded.”

“Aynsley was very technical, could drum anything,” picks up Huissen. “Then in came Mick Fleetwood. The first time I heard him play, I remember that I went to Peter and said, ‘Why did Aynsley go? I mean, for God’s sake – Mick Fleetwood?’ But then Peter said something to me that I’ll never forget. He said, ‘Mick’s got the feel, and that’s all that matters’. And it’s so true, because I can honestly tell you that Mick Fleetwood is my favourite drummer. The way he plays, the way he does it, it’s really incredible.”

John Mayall. Peter Green. John McVie. Mick Fleetwood. Blink and you’d have missed them. For just three months in early ’67, this mythologised line-up pounded what was arguably the most exciting blues circuit in history. “In those years,” notes Mayall, “we were working seven nights a week, and on the weekends you’d play doubles. I don’t think anybody in any given time can think of it in terms of ‘history’, because you’re just dealing with the daily round of shows. Your only concern was putting one foot in front of the other and getting out there. Getting in the van, y’know, setting up at the club, playing the gig. There was a lot of camaraderie in that line-up. A lot of humour. Otherwise, the music wouldn’t have sounded how it did. Sometimes they got out of control, but that was happening with all the bands at that time.

“Those clubs [on the tapes] were all part of our week’s work,” he adds, “and they were very rough-and-ready. Those types of places were a holdover: they’d been in operation with trad-jazz for many years. They were jam-packed, no room to sit down. It was a mass of bodies, all out there having a good time, having a drink, just enjoying the music and being a part of it.”

Huissen was among them. “I was a very difficult kid,” remembers the 65-year-old. “There was only one thing that me and my parents agreed upon: that I had to get out of the house, as soon as possible. I knew from the radio and magazines that something very big was happening in London. So I thought, ‘That’s the place I want to go’. And I’ve never regretted it. It was really the best time in my life. You’d go to one concert on Tuesday, another on Thursday. There was just one big vibe. Unbelievable. I saw the first Cream gigs, the first Jimi Hendrix gig at The Marquee…”

Pinballing between seminal shows across the capital’s clubland, it wasn’t long before Huissen fell in with Mayall and his foot soldiers. “Maybe ‘friends’ is a big word,” he considers. “But after the concerts, we sometimes went back to John’s flat. There was drinking, and you’d stay and sleep there. Very easy-going, but I remember, one time, John was pissed off because I went to see The Spencer Davis Group instead of his band! I was quite close with Peter. He really was the most kind and friendly guy that you can imagine. In 1967, there was nothing tragic about Peter Green.”

The Dutchman wasn’t just an observer, but also an avid bootlegger. “There was a group of eight of us – including Danny Kirwan – who went from concert to concert. It wasn’t some strategic plan. We just talked about how, y’know, wouldn’t it be great if after the concert we could hear the music again. I had a job at some office, just delivering the mail, and I had very little money, so I had to pay for the tape recorder in instalments. After the concerts, we’d go down in the tube and play the tapes, everybody looking at these crazy young guys making a lot of noise. Then the batteries would go low and there’d be no music anymore!”

Above: bassist John McVie [photo: John Slade].

Between February 1 and May 5, 1967, Huissen recorded five Bluesbreakers gigs at clubs including Brixton’s Ram Jam, Hampstead’s Klooks Kleek and Soho’s Marquee, each time positioning himself in the sonic sweet-spot. “I’d make sure that I was standing in the middle, because there was a great balance in the band. There was no PA at the time – only for singing – and no mixing desk. There was just one mic coming off the tape recorder, and on the original tapes, you can hear me shout, because I was nearest to the mic. I just couldn’t keep quiet, because the music was so great.”

Given his close relationship with the band, Huissen’s bootlegging of those five shows wasn’t quite as covert as has been suggested. “Y’know, I don’t want to undermine John,” he says, “because he’s talking about me sneaking in the tape recorder, which is of course a nice story. But, in fact, John knew that I was taping it. After concerts, I used to go to his flat, and so he heard those tapes. And not only had he heard those tapes, but he also copied them. So he already had those tapes. But what happened was, they all got lost in the fire, when his house burnt down in LA. It was a terrible tragedy, because everything he had saved – it had gone. Including the tapes.”

Awarded 10⁄10 by reviewer Hugh Fielder in this issue, it would indeed have been a tragedy if these performances had been lost to the flames. For fans of Green, in particular, Live In 1967 represents genuine treasure. “These tapes show Peter at his very finest,” nods Mayall. “I don’t think he’s ever played better. It’s quite an amazing accomplishment to actually have a recording of it all.”

“Peter had a hard job,” adds Huissen, “because he had to replace Eric, who was ‘God’ in those days. But after a couple of concerts, that whole idea was gone, because he was so amazing. What I remember about those concerts is that nobody was calling for Eric. They accepted Peter straight away. Well, you can hear the tapes. The way he played… it’s just phenomenal.”

Mayall: “I think the whole album captures that live freedom. You know, the improvisation and the energy that’s imparted to the audience. The audience are very much a part of that. They’re the ones who encourage you to take off. I think live performances are very different from studio recordings. There’s a lot more freedom, you’re not concerned with the actual performance as much as just communicating with the audience and exploring the music with total freedom. You’re not concerned with, ‘Oh, this might not sound too good if you listen to it back…’”

“If you look at the photo of Peter inside the CD, with his eyes closed,” continues Huissen, “that’s the way he was playing at those gigs. He was so into the music. You can’t play like that and not be interested. The intensity of those pictures tells the story. I remember that So Many Roads really made me cry. He got into the solo, and you went all the way along with him. My God – you were exhausted after he played that.”

“I’d have loved to have been a fly on the wall,” considers Corne. “I’ve never heard Mick Fleetwood playing in the Bluesbreakers, so to hear the chemistry of the four of them was really powerful. I was astounded at the chemistry between Mick Fleetwood and John McVie – back then, even – and at how confident they all are. Fleetwood’s drumming is just so confident.

Above: Mayall leads his troops [photo: John Slade].

“But to hear Peter Green at the height of his powers is exhilarating,” Corne continues. “I think he’s top-shelf and needs to be in the conversation about the all-time greats. His playing on Double Trouble and San-Ho-Zay is just unbelievable. I also thought it was cool to hear him play the songs from the ‘Beano’ record, like All Your Love. I love So Many Roads. And it’s funny, because I shared it with Walter Trout and he immediately texted and said, ‘Why did you fade out Peter Green’s solo?’ And I said, ‘I’d never do that – that’s how I got it!’ Clearly the tape must have been running out, and Tom was scrabbling to get another one out…”

“Yeah, it could have been that,” agrees Huissen, “because that happened a lot. On each side, you only had something like 35 minutes. So sometimes you had to quickly change a tape and use the other side.”

By the summer of 1967, it was all over. Fleetwood, then Green and finally McVie jumped ship to form Fleetwood Mac, while the Bluesbreakers rolled seamlessly into another golden era with Mayall’s recruitment of Mick Taylor. Huissen, meanwhile, boxed up his bootlegs. “I just had the tapes in a box in the cupboard,” he explains. “Twenty years ago, I spoke to John when he did a concert here in Amsterdam, but he was very busy. I sent him some stuff, but somehow it didn’t work out at that time.”

Mayall: “I’ve known about the tapes for quite a few years. In fact, Tom approached me a few years ago to see if I was interested in buying them. At that time, I didn’t have the money he was looking for. Also, I didn’t really have a clue as to the quality. He’d just given me a little taste, a few bars of each song. But more recently, I checked it out again and got in touch with Tom. By that time, he’d decided he wanted the world to hear these tapes. He didn’t want to keep them to himself any more. So we did a nice deal.”

Huissen: “At some point, you start to think, ‘Well, we need to fix this now’. Because, y’know, John is 81, so how long can you wait? He played here in my hometown, and I went to see him with all the tapes. The deal only took five seconds. He wanted the tapes, and I very much wanted the tapes to be officially part of his legacy. There are no other live recordings with John Mayallf eaturing PeterGreen. And the music and playing is just so great.”

With five shows to choose from, it chiefly fell to Mayall to cherry-pick material for two tracklistings (a second live album will be available later this year). “Well, yes and no,” Corne corrects us. “John whittled it down to the songs for the two albums, and he was pretty adamant that was the material to pull from. I think, as he’s listening to it, part of it is the bandleader listening, and part of it is the fan. He was so mesmerised by the performances. But I bonded with the songs, too, so we had a lot of back-and-forth. One thing about John is that even though he’s very resolute, he’s very reasonable. If you really make a strong case about why you feel something is in the best interests of the project, he will definitely listen. I’m pleased with what we got. The only song I didn’t get on there that I really wanted was Tears In My Eyes.”

The far greater task was to tidy up Huissen’s bootlegs for release. “This was 1967,” says the Dutchman. “There were a lot of dropouts. Some things we were able to repair, but some were not reparable. The tapes are the tapes, y’know?”

Corne gives a grim smile. “Yeah. What I got from Tom was a transfer that he did in Germany. I mean, the engineer in me would love to have had the multi-tracks, so I could have done some mixing. I took the five different shows and tried my best to make them consistent. Because not only is it poor quality, but there’s no separation. Everybody is on one track, in mono, so you don’t have the ability to turn anybody up or down. You can just kinda coax that with EQ and compression. The biggest goal for me was just to bring clarity to a very murky recording. So I got rid of as much of the boominess and tinniness as possible, without pulling the performances back too much. And then just cleaned up as much of the noise and hiss as possible.”

“You know, you have to deal with what you’ve got,” shrugs Mayall. “It was just whatever came into the tape recorder’s microphone, which was hand-held a few feet from the stage. That’s the sound you get. So there’s not much you can do about that, and I don’t think you should, really.”

“I think what everyone wants to hear is the performances,” picks up Corne. “And I think, in the end, even though this album still sounds like a bootleg, to my ears it has a cool, lo-fi 60s charm. As an engineer, if you can capture a vibe and an atmosphere, that’s half the battle. And I think this album is very vibey to listen to, actually.”

Maybe that’s the point. In an era when buffed, polished and Pro Tooled albums squeak benignly from our iPods, Live In 1967 deals in ragged atmosphere, dragging the listener back to London’s golden-era club circuit as effectively as any time machine. “I think the energy and the dedication to the blues is what comes across on those tapes,” notes Mayall. “It might not be very sophisticated, but it’s very raw and heartfelt. And it does capture those old days. It was such a long time ago. It’s a piece of history, isn’t it?”

Corne nods: “It’s really a historical document for British blues.”

As the man who originated the project, Huissen gets the final word. “If you listen to the CD,” he considers, “of course, it’s not 24-bit hi-fi audio. But what you hear is exactly how it sounded in The Marquee, The Manor House and Klooks Kleek. People say to me, ‘Oh, I wish I was there’. Well, with this album, in a certain way, you are. I was 16 then. I’m 65 now. But when I hear that music, I see myself standing there in the clubs again…”

Live In 1967 is out now on Forty Below Records.

What Happened Next

By the summer of ’67, Mayall’s line-up struck out as Fleetwood Mac. Here’s how the key players remember the split…

Mick Fleetwood: “The nicest way to put it is that John Mayall ‘let me go’ from the Bluesbreakers. Me and John McVie were wild men in that band, definitely partial to one or two. I realised we were getting too loose – loose as a goose – and a couple of gigs had been affected, and one of us had to go. But my thoughts of John Mayall are as someone who should be forever heralded as a mentor, who took so many players and showed them the way. I was then – and still am – a great friend.”

John Mayall: “Mick left first. Peter stayed a while. John stayed until Fleetwood Mac was established. So nothing ever happened all at once. There was no bombshell dropped. It was just time to move on.”

Tom Huissen: “John McVie did hesitate, because he did have a steady job, and with John Mayall, he was sure of some gigs and income, so he was a bit unsure if he should leave or not. Peter didn’t tell me he was going to leave, but I talked to him afterwards. It was a decision he felt he had to make, he felt he really had to do his own blues.”

John Mayall: “There’s obviously quite a lot of blues in Fleetwood Mac’s early days, but at the same time, I think the bent of the band was to be a little bit more commercial, perhaps.”

John Mayall: “Do I ever wish I’d had longer working with Peter? No. You can’t think in terms like that. Things have a natural way of showing themselves. If somebody feels they want to move on, then they have to move on, because they’ve got other things on their mind.”

Tom Huissen: “It was not so much getting famous. I think what actually happened [to Peter] was using the wrong drugs. A couple of years ago, me and my band, John The Revelator, we played with Peter and the Splinter Group here in Holland. He remembers me and it’s fine. But, yeah, something happened that was very, very sad.”

Eric Corne: “John speaks very fondly of all of them.”

John Mayall: “Have the other band members heard Live In 1967 yet? Well, Fleetwood Mac is on the road right now, so I’ve sent copies to John’s address. He hasn’t got home, so I haven’t heard back yet, but they’re waiting for him when he gets off the road, and there’s a copy there for Mick. Peter is off the radar – I have no idea how to contact him. But I hope, somewhere along the line, someone will get a copy to him…”

Henry Yates has been a freelance journalist since 2002 and written about music for titles including The Guardian, The Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a music pundit on Times Radio and BBC TV, and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl, Marilyn Manson, Kiefer Sutherland and many more.