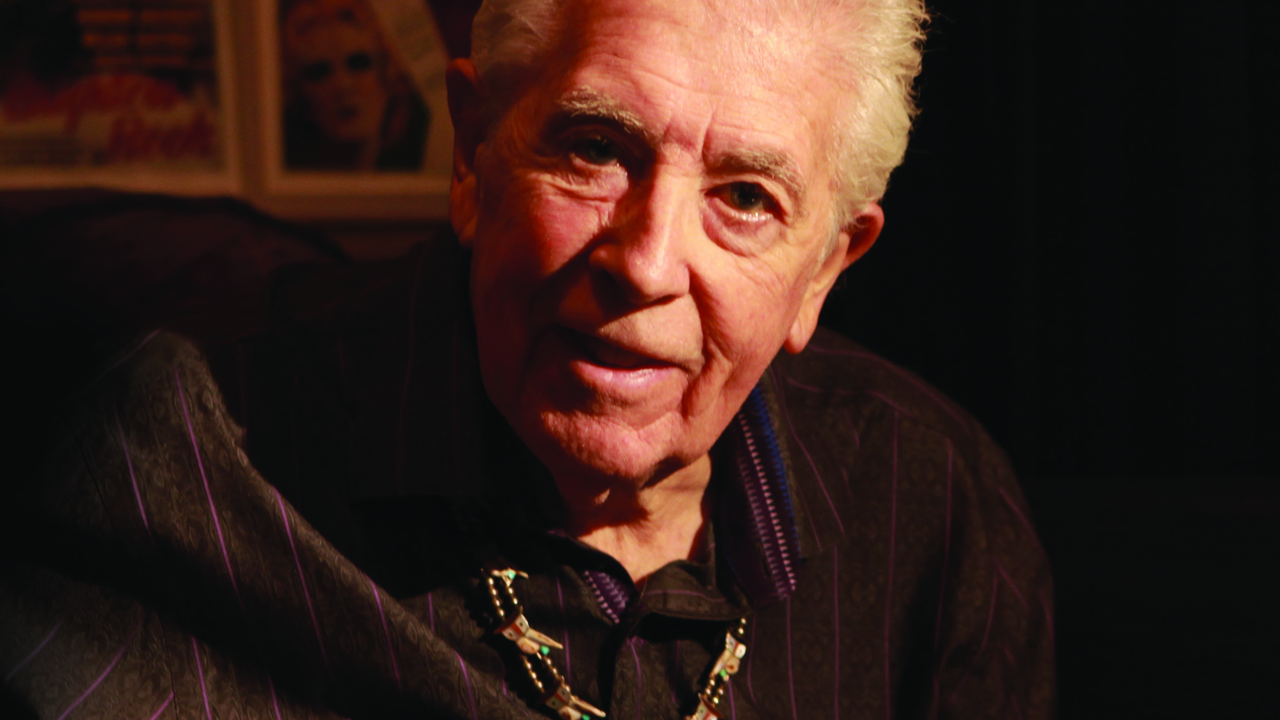

John Mayall: The Hard Road

Having been the kingpin of the British blues scene since the mid-60s, John Mayall is showing no sign of throwing in the towel just yet, as he releases his new album and hits the live trail...

It’s only natural to talk of retirement when you reach your eighties – some might say that’s leaving it a little late – but John Mayall hasn’t got round to it yet. On the cusp of his 82nd birthday he gives no indication that he’s going to quit what he’s been doing for the last six decades.

That hasn’t stopped others talking on his behalf though, possibly out of a desire to wrap up his outstanding career in ribbons and bows. There were murmurs back in 2003 after his 70th birthday concert in Liverpool that featured appearances from two of his illustrious former guitarists, Eric Clapton and Mick Taylor. But there was no perceptible change in Mayall’s relentless touring schedule, and the albums continued to emerge on a regular basis.

Five years later the murmurs rose up again when Mayall himself used the “r” word after dissolving the backing band who’d been with him for 16 years. But it turned out that the only thing that was being retired was the Bluesbreakers moniker – three weeks later Mayall had recruited a new band and was back out on the road.

Then the albums dried up after 2009’s Tough, raising further speculation that was only quelled by last year’s A Special Life. And now, a year later, comes another album of new material, Find A Way To Care, to underline that normal service has been resumed. Mayall himself can’t see what all the fuss is about. The interruption was just another blip from a record industry still trying to get to grips with the digital age.

“We were with Eagle Records who were increasingly slow to the point of standstill,” he explains down the phone from his Los Angeles home, where yet another sunny morning vindicates his decision to move to America’s west coast more than 40 years ago. His accent, though, remains resolutely British, without even a hint of the mid-Atlantic squawk that afflicts so many of the long-term expats living out there.

“Maybe they were going through financial problems, I don’t really know, but they just didn’t ask for a new album,” he continues. “In the meantime I put out a couple of albums on the website, to hold the fort so to speak.” These included the CD/DVD Live In London, which was recorded at the Leicester Square Theatre in November 2010 featuring his current band. “We just did the best we could until Eagle finally decided they weren’t going to deal with us any more. I kind of forced their hand by saying: ‘We can’t keep hanging around like this.’ And they gave me the okay to go ahead on my own. That allowed me to make a deal with producer Eric Corne and his Forty Below record label.”

Linking up with Corne, one of a new generation of producers working in Los Angeles, rejuvenated Mayall’s sound on A Special Life and is even more evident on *Find *A Way To Care. Mayall describes it as “a great experience” while Corne was so excited when they first met he dropped any pretence of cool and asked Mayall to autograph his copy of the Beano album. “I first came into contact with Eric when he was making an album with Walter Trout and they wanted me to do a spot on one of the tracks,” says Mayall. “So that’s how I came to meet him and see the House Of Blues studio. He runs a small outfit and he’s very hands-on, which is perfect for me because he gets the job done. It may not be the biggest record company in the world but we’re certainly getting a lot more attention and publicity and everything else through being with him.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

So well has their relationship developed that Mayall entrusted Corne with the historic tapes of the Peter Green/ Mick Fleetwood/John McVie Bluesbreakers line-up recorded at various London venues by an eager Dutch teenager with a single mic and a portable reel-to-reel, and finally released earlier this year as Live In 1967. “Actually the tapes were in pretty good shape in the first place,” says Mayall. “Eric just sweetened them up a little bit, particularly at the beginning and end of the songs, overlapping the sounds of the audience from the different venues just to make it sound a bit more realistic. The good thing is that there’s enough there for another album, which will be coming out next year.” Hopefully Corne now has a signed copy of A Hard Road to add to his collection.

Mayall’s preparations for his latest studio album followed a tried and trusted pattern, bolstered by his growing familiarity with his band. “I’ve had the same band together now for six years and it’s got to the point where we now all think alike, so the album came together very quickly. As regards the material, it was just a round-up of songs that I thought would be suitable for the line-up. It was also nice to have the horns on three of the tracks. It made a good embellishment.

“When I make an album I try to make it as varied as possible with as much interest and different flavours as I can. And this one turned out well

I think. I ended up playing a lot more keyboards on this one than I usually do. That wasn’t necessarily planned at the beginning but it was just the way it all came out. It seemed to grow out of the material.”

Corne also encouraged a greater emphasis on Mayall’s keyboard contributions, believing they’d been undervalued on recent albums. And the solo that enlivens Mayall’s own Ain’t No Guarantees proves that their instincts were right. “Yes, it just races along doesn’t it?” Mayall enthuses. “I made a demo of that song a little while ago and I thought it was something that would work out for a band number. When I played it to the guys I realised that it had a great beat and it really put them on their toes to get that kind of propulsion.”

The expansive piano solo on Long Summer Days, is another fine example. “I enjoyed that one,” he agrees. “Part of it was that there were so many interesting keyboards lying around at the studio that I got to have a go on. It just added to the variety.” A further addition to the variety is a rare co-write on Ropes And Chains with bassist Greg Rzab. “That was something fun we did. He wrote the music and I put a story on top of it based on the mood of the music that he’d sent me.”

When it comes to picking covers, Mayall’s talent for reviving some forgotten gems alongside more familiar songs remains as sharp as ever. “Well, there’s just so much great material out there, whether it’s obscure or more well known. But I have a large record collection and it takes me an afternoon to go through a few songs and decide which would be suitable for my voice and I just pick them from there. So it’s not a very lengthy process to pick songs. I think if you asked me to put together another album next week I could probably come up with it.” And he agrees that there are worse ways to spend an afternoon. “It’s always a pleasure. I usually look for songs that have a particular feel to them, maybe a different instrumentation, and they start coming together very easily.”

He’s not bothered about what format he listens to them on either. “I don’t care whether it’s tape or whatever medium it’s on. I’m not one of those people who has to have the original 78 or whatever. As long as I can hear the music that’s fine. To be honest I can’t hear the difference between a lot of these formats. I’m not really listening in that way.” But he’s happy to meet the demands of the growing market in vinyl. “My recent albums are also available on vinyl. It’s more expensive but it’s worth it to please the die-hard fans.” Sadly, Mayall’s first legendary record collection – back in the days when vinyl was the only format in town – was destroyed when his Laurel Canyon house burnt down in 1979, leaving him with “just the clothes on my back”.

One of the more intriguing covers is Percy Mayfield’s The River’s Invitation from the early 50s. It’s been covered by, among others, Aretha Franklin and Joe Cocker, who brought out the song’s soul elements, but Mayall remembers an Alexis Korner version from the early 60s. “He did it in 3⁄4 time, whereas the others are in the straight-ahead blues beat. I always liked the horn arrangements for the song and got my players to follow that.” There’s also a swooping bass groove on the song that brings a distinctive touch. “Yeah, it was funny the way that all came about. Greg was doing the track and he was doing fine, but then someone brought in a fretless bass for him to have a go on and he thought it was just the perfect instrument for the song. So it all happened quite spontaneously.”

It’s a perfect example of how Mayall gives his band freedom to explore. “I trust the musicians in my band implicitly, and any ideas they come up with are just part of their own thoughts and make- up. I don’t tell anybody what to do. Anything they come up with is going to be the right thing. In the studio the whole idea is to have a lot of creative fun at the session. In fact the band laid down all the tracks for the album in three days. The whole thing only took a week. Spontaneity is the key and you generally get that on the first take. I never normally do more than two takes.”

Some of Mayall’s contemporaries could spend longer setting up the mics for a tambourine overdub than it takes him to make an entire album. “I’ve never understood how anybody can do that,” he muses. ”You hear about bands like The Rolling Stones taking a year to make an album and I just can’t imagine what they’re doing all that time. They must be taking a lot of time off one way and another.”

He doesn’t take long preparing songs for the studio either. “I don’t read or write music, so after I’ve made the selection I’ll send them off to the band so they have an idea of what they’re all about and what key they’re in, and then we’ll go in and do it. It’s a very instant kind of thing.” The same applies to the horn arrangements. “On The River’s Invitation they used the original arrangements. That was a no-brainer. But when it came to the title track I left it up to them. There’s very little direction where the horns should be and if they’re the right people then they can take it from there. When they come in they play me what they’ve got and it’s usually the right thing.”

Obviously Mayall has the right of veto in the studio, but it’s not an option he uses. “I can’t recall that happening. It’s always been right. The whole idea is to enjoy playing together and creating. The operative word is playing; playing in the sense of having fun. We just play as we would do on stage. And it all comes together. Eric Corne knows exactly what to do to catch the right sound from each instrument.”

The mix of covers includes less familiar names like Lonnie Brooks’ I Want All My Money Back (“it’s got an aggressive tone to it and a lovely attitude”) and Lightnin’ Hopkins’ I Feel So Bad (“there’s something very real there”) together with Charles Brown’s Drifting Blues (“I love the lyrics and the feel of it”) and Muddy Waters’ Long Distance Call (“that was an opportunity for me to play some lead guitar. I knew exactly what the feel of that was supposed to be from listening to it as a teenager”).

But he also keeps his ear to the ground, finding songs like War We Wage from young bluesman Matt Schofield. “We did a show with him on the last European tour and his band was really terrific. So I got his CDs and that was the song that stuck out for me. I liked the lyrics and the mood of it. He was also really happy with us recording it.” The song’s simple message also fits in with Mayall’s own observational technique. “You can find something to relate to every time you pick up a newspaper,” he says. “I read newspapers but I don’t ever watch TV news; I find what they’re saying is irrelevant to me.” One of the downsides of living in America.

In contrast, one of the upsides of being based in the United States is the much larger pool of musicians he can draw on to form his band. As a result, his band line-ups have been much more settled than they were when he lived in the UK. “The last of the Bluesbreakers bands was together 16 years. And the band before that was together 10 years,” he confirms. “I think there’s a misconception by people who just think of the early days in the 60s when the band changed fairly frequently. The musicians that I was playing with back then were young and they were learning their craft and finding their direction. My band was a good platform for them to explore their own talent. But after a while they’d want to move on”

Mayall never complained about that at the time, and doesn’t now. “When somebody’s ready to move on you can start to feel it; their mind is somewhere else. My job was to recognise that and understand it. That in turn gave me the opportunity to freshen my ideas up when a new musician arrived and see what he had to contribute. It changes the dynamic and it’s all part of the excitement of doing something new.”

One thing Mayall’s bands can rely on is that they will be working. “Well, the road goes on and I don’t take breaks,” he laughs. “There hasn’t been a year when I haven’t been working full-time. That’s why I call it a special life. It does everybody good to be out there in front of an audience getting that feedback. When I get up on stage I want to give the audience a good show. And every show is different. We don’t play the same set every night. I make up a set-list probably an hour before we go on and the band are always excited to see what I’ve come up with. At the moment we’ve probably got about 40 songs that we play regularly. And you can mix that up into any number of different permutations. I try to have a bit of everything at each show. I do a smattering of songs from the 60s and other different periods of my career.

“If you’re playing back-to-back towns or cities that are fairly near to each other, anyone who comes to both shows will see a different set. And of course if we’re playing two nights in the same place we will play a completely different set. I always make a point of telling the audience that. And it’s become something we are known for – come for a second helping and get a completely different set. And of course it gives me more opportunity to showcase my blues heroes and tell people about them.”

I make my living on the road. We’ll keep going as long as there’s interest out there from the fans.

Having lived and worked on both sides of the Atlantic, Mayall has experienced an international life. So how does he find the blues scene in the US compares with Britain and Europe? “In the States the main amount of work we do seems to be on the east coast. The west coast is not so good for getting gigs; the money isn’t there and people don’t seem to be as interested as they are on the east coast.

But that doesn’t compare with the reaction we get in Europe. They seem to be more keen on American music because they don’t have that access to it on a daily basis. They don’t take it for granted and it’s a big deal when an American artist comes over to Europe.”

That explains why Mayall’s upcoming European tour – which includes three nights at London’s Ronnie Scott’s Club – is two and a half months long. “There’s only three days off in that time,” he adds with a certain amount of pride. “Not consecutive, but here and there so we can get from one part of Europe to another. It’s just part of the whole adventure.” Not surprisingly, Mayall keeps it simple on tour. “We don’t do soundchecks. We don’t have a sound man either. We use the house engineers. It’s hard for people to realise how simple we make it. Once they’ve got the levels of the instruments, that’s all they need to know to get the right sound, assuming they know the acoustics of their own hall. It just lets us get on with the work of playing and supplying the dynamics.

“Sometimes it’s a bit hit-and-miss but we just take it as it comes. If something goes wrong for whatever reason, I make sure that it’s all part of the fun of the show and the audience are in on the joke. If a microphone doesn’t work it’s quite obvious and I make a thing out of it. That happened on our last tour. The microphone stopped working twice and the second time it happened and the sound engineer came running on stage and started fiddling about with it, I just got off stage and went and sat in the audience and started cat-calling him. Everybody in the audience was tickled with that one. There were people standing up and taking pictures.”

Having always made his living from playing live rather than relying on record company income, Mayall is probably better placed than most to withstand the continuing turmoil in the record industry. “For as long as I can remember we’ve been doing over a hundred shows a year around the world. There’s no shortage of places out there to play for live performers, it’s just the record business that’s lagging.

“It’s hard to tell what other bands are doing, but I make my living basically from the road. The records are out there to do what they do. I’ve never had a hit record so I don’t know what the income would be like. So we just play. We’ll keep on going as long as there’s interest out there from the fans.”

Find A Way To Care is out now via Forty Below. His UK shows begin in London on November 2.

All-Star Cast

How Mayall nurtured the world’s best guitarists.

**ERIC CLAPTON

**God was never going to slum it as a sideman forever, and even before he split for Cream, he was acting like a star. (“I was only half there,” he noted in ‘94. “I was so unreliable, so irresponsible.”) Mayall told The Blues that Clapton sometimes “phoned it in”, but even at half-stretch, his playing on Beano is sublime.

**PETER GREEN

Forget the messianic robes, the drug-fuelled meltdown and that alleged incident with the air rifle. Instead, revisit ’Breakers standouts like *Sitting In The Rain*, Picture On The Wall and The Supernatural – and fall to your knees at that spellbinding touch.

**MICK TAYLOR

While Green’s exit would have killed most bands, Mayall simply recruited a precocious teenage introvert and rolled into another vintage period. *Blues From Laurel Canyon* suggested Taylor could have topped the heights of his forebears – instead, he chose to be chewed up and spat out by the Stones.

**WALTER TROUT

**Trout was a risky bet in 1985, but Mayall looked past the rampant alcoholism to coax out stunning moments like One Life To Live. The Bluesbreakers’ most rocking period ended in 1989, when the guitarist beat the bottle and embarked on his solo career.

**COCO MONTOYA

**Having cut his teeth through the 70s in the Albert Collins band, Montoya offset Trout’s blazing leads with his Albert King-influenced ‘upside-down’ style. “I would never be doing what I’m doing now,” he reflects, “if I hadn’t gotten the phone call from John Mayall.”

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.