The canvas on which John Mellencamp is at work on this glorious late-summer morning stands two feet taller than he does and is the width of his outstretched arms. Evolving on it is a representation of a young woman, rendered in bold black strokes, limbs and features exaggerated so she appears to be not quite human. Bedraggled on a chair, she clutches in one hand the outline of an empty bottle and in the other that of a broken violin, frozen in this ruined state. This striking but bleak tableau is consistent with Mellencamp’s stock-in-trade as an artist – one noted American art critic wrote of his propensity for “handsomely grotesque portraits in oil that are solemn and stirring”.

Mellencamp has been painting seriously for more than 40 years and his work is both acclaimed and prized in his home country. Since last year an exhibition, baldly titled The Paintings Of John Mellencamp, has been touring US museums and galleries. Today the man who once gave himself the nickname Little Bastard looks the part of the studious artist, standing among his oils and brushes in paint-splattered overalls, a pair of reading glasses perched on the tip of his nose.

There are subtle clues to his other, and still main, profession: the pompadour of ink-black hair that crowns his head, the faded tattoo on an upper arm as thick as a slab of meat; Brown Sugar by the Rolling Stones booms out from a set of expensive speakers, and an acoustic guitar and vintage amp are tucked away in a corner.

More obvious is the immediate visible evidence of what can be acquired from selling more than 40 million records. Not least this very art studio, gleaming from the outside like a space-age barn with its arched roof of dazzling corrugated metal. Set within acres of South Indiana forest, its floor-to-ceiling windows afford an unbroken vista of walnut, sycamore and witch hazel trees, their leaves turning to autumnal gold; sunlight dances and dapples across an interior furnished in dark wood and chrome.

Located a mile or so down a rough woodland track, Mellencamp’s home is an even more imposing ranch house made of brick and stone, looking out on to the picturesque expanse of Lake Monroe. A few years back when he released a splenetic song savaging the American invasion of Iraq, titled To Washington, outraged good old boys lined up in paddle boats to hurl abuse at him from the water. The only interlopers circling today are squadrons of hawks high in the clear blue sky. Mellencamp has just returned from playing the annual Farm Aid concert in Raleigh, North Carolina. He co-founded this charitable organisation in 1985 with Neil Young and Willie Nelson to aid America’s embattled family farmers and it has since raised more than $45 million.

“My eldest son, Hud, came out,” he says, smiling. “And I’d never seen him do this before, ever, but he got down in the photographers’ pit and was dancing and singing along to my songs. I didn’t even know he knew any of the words. He once told me he turned my records off when they came on the radio. Said he was sure that sooner or later a song was gonna go: ‘Goddammit, Hud!’”

Mellencamp emits a rattling laugh and lights the first of many cigarettes. Doctors told him to quit smoking in 1994 when he suffered a heart attack after a show in New York, aged 42. He paid them no heed, and protests that this is his sole remaining vice. He swore off booze and drugs in his early 20s after being hospitalised after a bar fight. To both he ascribed the debilitating panic attacks he suffered at the time and that have continued to afflict him ever since.

Now a bullish 63, he’s a three-times-divorced father-of-five and a proud grandfather. For the first time in as long as he can remember, he is single, following his split from actress Meg Ryan in May. The pair dated for three years in the full glare of America’s tabloids (“Actors stay on script for the first forty pages and then start to ad-lib, which is hard to get past,” he explains of their parting). He claims to take great delight in his own company.

“Fact is, I’m a cranky old man,” he says, measuring out each word in a deep burr. “So it’s best that I keep to myself, do things my way. A lot of people my age are ready to fold up the tent and go home. It hasn’t worked out that way for me. I’m still learning, still excited and I’m looking for trouble. But as far as me being a jolly fellow goes… Not yet.”

This sentiment runs through Troubled Man, the folksy opening track on Plain Spoken, his just-released 22nd studio album and one of his best. At one point in the song, Mellencamp croons as wistfully as an undertaker: ‘I laughed out loud once/I won’t do that again.’

“Happiness is not a normal state to be in,” he says. “If you see a guy who’s happy all the time then there’s something fucking wrong with him, he’s on drugs or drunk. We should live to work and toil like galley slaves. It fulfils the mind, the body and the soul.”

John Mellencamp entered this world in the small mill town of Seymour, Indiana on October 7, 1951. His great grandfather, also named John, came to the US from Hannover, Germany and settled in the Midwest, marrying a black woman, marking him out in those segregated times. Mellencamp detects her legacy in the broad shape of his own nose and in how his own views on race and tolerance were formed. From his father and mother he claims to have inherited respectively heart disease and diabetes, and from both a quick temper. The 50s heralded a post-war baby boom in the US, and Mellencamp was one of five children born to his parents: three sons and two daughters.

“I had a good childhood,” he says. “Everybody was having babies. I never ran out of kids to play with or trouble to get into. Back then it wasn’t like now where folks have to keep their eyes on their kids all the time. When we were growing up, parents didn’t give a fuck where their kids were. It was like: ‘Shut the fuck up and get the fuck out.’”

An abundance of playmates aside, the young Mellencamp was especially fortunate in at least one other respect. He was born with spina bifada, a congenital disorder that leaves the nerves of the spine exposed. In 1951 the condition was barely treated and frequently fatal. However, Mellencamp was under the care of a crusading doctor at Riley Hospital in Indianapolis and became the recipient of ground-breaking and life-saving surgery.“Every day of my life my grandmother told me: ‘John, you’re the luckiest boy in the world and don’t you forget it,’” he recalls. “You hear that often enough and you believe it. What that did to me was give me great confidence in anything that I tried to do.”

At high school Mellencamp was a track and football star. But soon enough he turned his talents to chasing girls and playing in bar bands around the local roughhouses. The first of these was a mixed-race soul band named Crepe Soul, which he joined at the age of 14.

“That was where I really learnt about race in America,” he says. “It was a mostly black band with a couple of white guys. They loved us when we were on stage, but not so much when we came off. The word ‘nigger’ was thrown around a lot. I was a ‘nigger lover’.

“If you wanted to be in the Crepe Soul you had to have a blackjack, which is a strip of leather with a sharp piece of steel nailed through it. You held it around your hand and whacked guys on the head with it in bar fights. It was good to mix it up with a bunch of hillbillies. I wouldn’t trade it for a million bucks.”

By the time he was 18, Mellencamp was making $200 a night from playing music, a small fortune in the late 60s. He also fathered a daughter, Michelle, and eloped to get married to her mother, Priscilla Esterline. Nineteen years later Michelle would make him a grandparent at the age of 37. He dismisses the notion that fatherhood might have made him grow up fast.

“It gave my wife a grasp of being responsible, not me,” he avers. “She took care of me, our child and all these fucking guys in bands that I hung around with. My idea of parenting was throwing water balloons at my kid. It was a knock-down/drag-out relationship. A lot of the time we were living with her parents. It wasn’t bad. I had a motorcycle, a guitar, a good stereo and a little change jingling around in my pocket. At that time of my life, that was all I wanted.”

Eventually Mellencamp took off for New York looking for a record deal. He hooked up with David Bowie’s ex-manager, Tony DeFries, and then Rod Stewart’s, Billy Gaff, and made a brace of flop albums under a nom de plume DeFries foisted upon him – Johnny Cougar. In the early 80s he struck gold with the American Fool album, which sold five million copies in the US and spawned a No.1 single, Jack & Diane, the spikiest of the lightweight pop-rock tunes he was then writing.

Later in the decade he reverted to his birth name and transformed into a pugnacious blue-collar rocker with a social conscience, like Bruce Springsteen but with rougher edges. Records such as 1985’s Scarecrow and 1987’s The Lonesome Jubilee were multi-platinum blockbusters and also critically acclaimed. /o:p

Yet Mellencamp never seemed to be satisfied. He developed a reputation for resolving disputes with his fists, He got divorced twice./o:p

“I was always mad about something,” he says. “Because when you play the game, there are too many people to have to depend on. The Lonesome Jubilee tour was the biggest-grossing in the world that year, and I was never so miserable in my life. I was mad at the audience all the time. There are 25,000 people cheering for you and you’re mad at them because it’s their fault you’ve got to be there? Even I knew that was fucked up. It slowly dawned on me that I didn’t want to be a pop singer.”/o:p

These days Mellencamp dismisses most of the records he made in the 90s as production-line jobs, knocked out to keep the gravy train rolling. He reached a nadir with Dance Naked, tossed off in a week in 1994, having laid a bet he could record a hit in that time – and winning. He married a model, Elaine Irwin, and after his heart attack he quit making music to raise their sons, Hud and Speck, back home in rural Indiana.

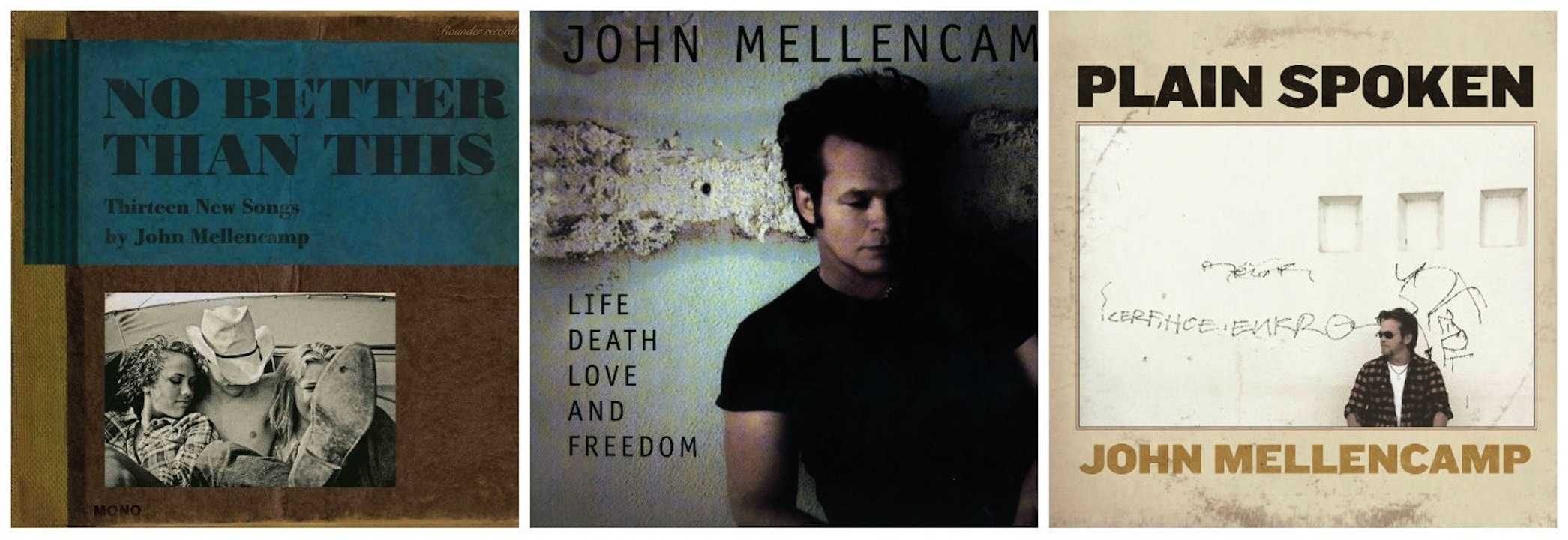

He re-emerged in the 00s, recasting himself once more, as a folk singer and ruminating on the human condition on a pair of finely detailed records: Life, Death, Love And Freedom and No Better Than This. Both were produced by T Bone Burnett, who had piloted Robert Plant and Alison Krauss’s Grammy-winning collaboration on Raising Sand, and he likewise stripped Mellencamp’s music of artifice and affectation, paring it down to its heart and soul.

Plain Spoken continues this thread, with Burnett returning as executive producer and Mellencamp crafting 10 raw-to-the-bone songs that sound as intimate as field recordings. The sense of resigned melancholy at the core of tracks such as The Isolation Of Mister and Tears In Vain begs to be seen through the prism of his break-ups with Irwin and Ryan, although he dismisses this idea.

“A lot of the songs, I don’t know what the fuck they’re about,” he counters. “I’m an observer of other people too, and I’m always open to ideas and able to channel them. My inspirations in the last ten, fifteen years aren’t drawn from rock’n’roll; I’m looking at William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, John Steinbeck, these great American authors and what they wrote about. It’s about as far from popular music as you can get. But I’ve lost contact with that world. I’m not interested in entertaining teenagers or acting like one. I have zero interest in looking back, don’t give a fuck. If I was one of those guys that gets up there and tries to behave the same way I did when I was thirty-four I’d kill myself. I’d just as soon blow my fucking head off.”

Nonetheless, Mellencamp is acutely aware of time stalking him. Next year he will undertake his most extensive tour of the US in decades, with a run of 80 dates beginning in January. Initially he passes this endeavour off as nothing more than “something to keep me off the streets”, but when pressed further admits to wanting to make the most of his twilight years.

“Look at Dylan, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash. All these guys started playing so much the older they got because they knew that time was running out,” he says. “I’ve realised that all I’m really good at is writing songs, recording them and playing them. The rest of it I don’t care about.

“Let’s face it, I may have twenty years left or I could die tomorrow. You don’t have that sense when you’re thirty-four – life looks stretched out forever in front of you. The realisation that it isn’t changes your whole world view. My dad is eighty-three and he says the same thing to me every goddamn day: ‘You do anything fun today?’ ‘No, dad, just working.’ ‘You better knock that shit off, it don’t mean nothing.’ Here’s the same guy that when I was a kid would tell me: ‘You’ve got to work.’

“And he’s right, it don’t mean shit,” he concludes, contradicting his earlier statement about the value of toil. “The next generation aren’t going to care; they’re not even going to remember who you were.”

Until he heads out on the road, at home Mellencamp will keep to the same routine. He gets up each morning at 9.30am on the dot, never earlier, as specified as the time a gentleman should rise in Amy Vanderbilt’s 1950s bestseller Complete Book of Etiquette (“I don’t make the rules, I just follow ’em,” he says). A night owl, he paints through the day, goes for a workout in his gym down at the house before dinner, and then occupies himself taking care of business or reading till two or three in the morning.

Of late, storm clouds have stirred his reverie. The previous summer his two sons were indicted on felony battery charges – accused of beating a man so badly in a brawl at a local bar that he required plastic surgery. The case is still rumbling its way through the courts, though Mellencamp suggests it will “go away pretty soon”. The interest surrounding it intensified last June when Mellencamp turned up on the Late Show With David Letterman sporting a black eye, stating he’d got it in a set-to with his youngest boy, 19-year-old Speck.

“Speck’s a real fucking handful,” he says, sighing deeply. “He’s looking for trouble and he’s going to do every fucking thing the hard way. I was so surprised when he hit me, did not see it coming. Afterwards he claimed I’d been giving him shit, and I’d always told him not to take shit from anybody. There’s not a lot I could do about it – kid’s six-two and weighs two hundred and twenty pounds. I mean, I’d have to pick up a bat.

“But then everybody that’s been around says that he acts just like I used to. I guess that’s the kind of hard-head I was. Things would’ve been a whole lot easier for me if I’d just kept my mouth shut and head down, played the game, shook hands and kissed some ass. But I can’t do it.”

The matter of troubled sons – and also that of murder, betrayal and guilt – is central to Ghost Brothers Of Darkland County, the southern gothic-themed musical that Mellencamp co-wrote with his friend, the horror author Stephen King, and which toured the States last year to mixed notices. In November it begins a further run at various US theatres with Gina Gershon (Killer Joe) and Billy Burke (of the Twilight films) in the lead roles. Mellencamp says he found the ideal collaborator and soulmate in Stephen King.

“We’re like peas in a pod,” he says. “I don’t even know how Steve sold a book. He’s a fucking hillbilly and he does not give a shit. He has a very successful TV show right now called Under The Dome, taken from one of his books. He agreed to write three episodes for it and quit after one. He told me it was work for fucking morons. You have to take your hat off to guys like that.”

The subtext, of course, is that John Mellencamp is also the real deal. But the afternoon sun is bearing down and he has a painting to be getting on with. He motions to another canvas propped against the wall, a portrait of him and his most recent ex-wife staring out at the viewer through pitch-black eyes, the pair of them younger and still then joined together.

“That painting,” he says, “I’ve been fucking around with it for ten years. See, I didn’t understand the value of taking time and care when I was kid. Sure, there are some things you only learn with age – that is, if you’re capable of learning. And, fuck,” he gasps, peering intently at this work in progress as if for the first time, “that’s what I looked like when I started painting it.”

And what of the bigger picture – of how Mellencamp would want his life’s work to be perceived and judged?

“Oh, I don’t give a shit,” he shoots back, chuckling. “All of this is for my own benefit. What do I care? There is only one critic that matters and that’s time. And I’m ready to roll with time, because initially Johnny Cougar was not going to amount to a hill of beans. But, son of a bitch, he’s still hanging around forty-three fucking years later.”