Listening to John Renbourn was really like eavesdropping on a conversation between the musician and the music itself.

His playing was a gentle but persistent interrogation of melody and harmony, involving a persistent, inquisitive approach that wore its obviously prodigious technique lightly and without any undue fanfare or grandstanding. His immense generosity as a player made him the perfect accompanist; quick to support others with exactly the right amount of deference without ever compromising the integrity or strength of the piece in hand. This aspect of Renbourn’s character might help account for the chemistry that underpinned the success of his collaboration with Bert Jansch. 1966’s Bert And John, with its smoky, pungent mix of blues, jazz and folk, while owing something to Davy Graham’s influence, possessed its own distinctive tightly woven vocabulary which they would develop and extend with the formation of Pentangle in 1967. Along with Danny Thompson (bass) Jacqui McShee (vocals) and Terry Cox (drums and percussion), the run of four albums from their 1968 self-titled debut through to 1970s spellbinding Cruel Sister represent an artistic highpoint in collaborative acoustic-based progressive music.

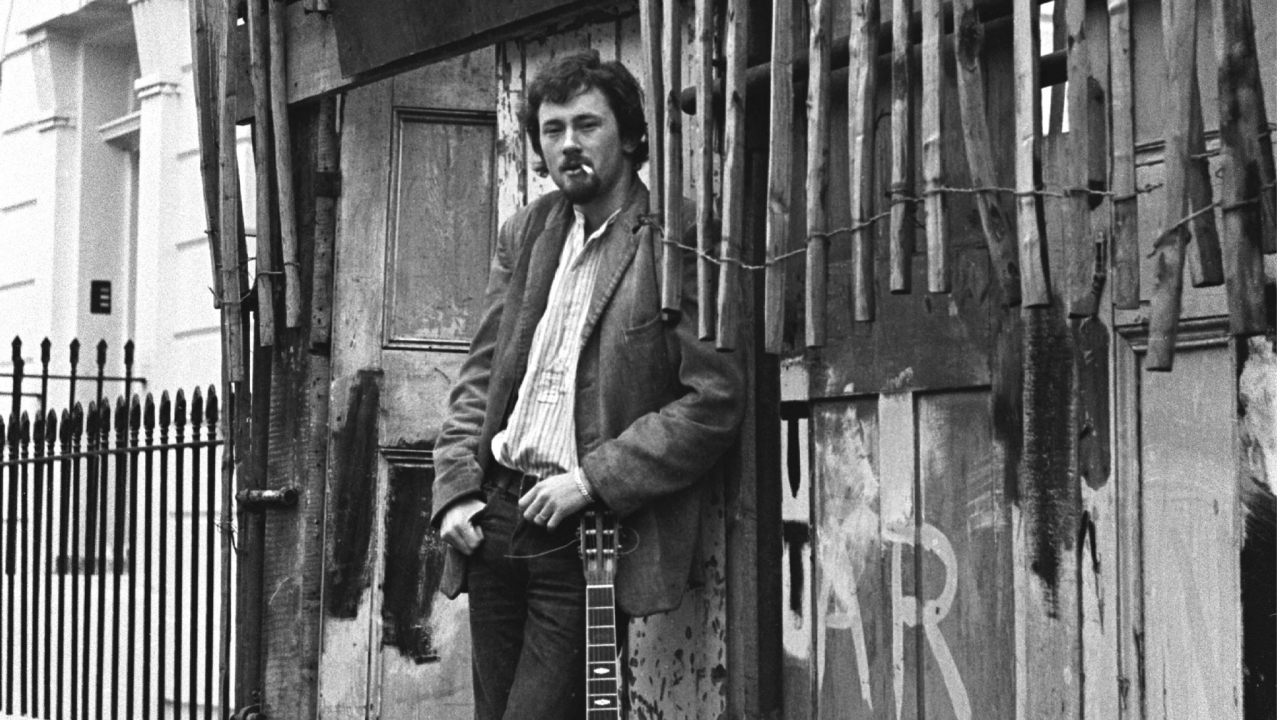

(Pic: Getty)

The love and respect Pentangle gathered in the years following their split in 1973 was given voice in the rave reviews and near universal praise they received when the band re-formed in 2008. Renbourn was always diffident about his ‘fame’ recalling that on one occasion: “I was coming into the country from abroad and the immigration guy looked at my passport and said ‘‘ere I’ve ‘eard of you, mate.’ Like an idiot I said, ‘And you’re still letting me back in the country?’ He said, ‘Any reason I shouldn’t? Step this way, sir.’ And he took me to one side to search through all my stuff!”

His use of the sitar - bought from Alexis Korner in the early 60s for £20 when he and Jansch were flat-sharing - lent a certain exoticism to Pentangle’s sound that was revived when the band re-formed. Renbourn was ‘under orders‘, as he described it, to use the venerable instrument once again. In concert he would humorously huff and puff as he got down from his stool to sit cross-legged on the floor to play it. Though happy to have used it, he was quick to admit that he did little more than scratch the surface of the instrument’s potential. “The real truth is,” he told me in 2011, “a sitar is a 24-hour job much more than a guitar.”

Alongside his masterly grasp of traditional music from various points of the compass, Renbourn relished the exposure to classical music he received when studying for a music degree at Dartington College in the 1980s, hungrily devouring everything from the stately forms of Bach to the more acerbic and challenging terrain of Schoenberg.

Justifiably his work beyond Pentangle was lauded for its invention and subtlety. His third solo album released in 1968, Sir John Alot of Merry Englandes Musyk Thynge and ye Grene Knyghte, audaciously connected traditional early English music to contemporary motifs with consummate style to create not a backwards-looking collection but something that is timeless, and an essential item in any serious music fan’s collection. Wheel Of Fortune, recorded with Incredible String Band’s Robin Williamson in 1993, was another demonstration of his astonishing empathy and immense talent for making every note count.

(Pic: Getty)

His final solo album in 2011, Palermo Snow demonstrated he’d lost none of his ear for a fine tune turned out simply and with elegance. Of the album he hoped that the record will appeal to people who respond to musical content rather than categories. Renbourn had little time for the purist wing of the folk police who objected to the cultural melange which he worked into his music from the very beginning of his career, hailing from a time when even bringing a guitar into some folk venues of the day was to invite scorn and a booing off the stage. Barriers in music were anathema to him and many of his contemporaries, arguing instead that there was only really jumping off points for exploration and investigation. It wasn’t in his nature to worry too much about posterity but throughout his years as a professional player he took the view that those who pushed and experimented would be the one’s whose music would have real value and stand the test of time. He wasn’t wrong.