Journey’s landmark 1981 album Escape is more than just the home of Don’t Stop Believin’ – it’s one of rock’s greatest records. In 2010, ex-singer Steve Perry and longtime keyboard player Jonathan Cain looked back on the making of a masterpiece

“It was like a water balloon being sliced by a slow razor.”

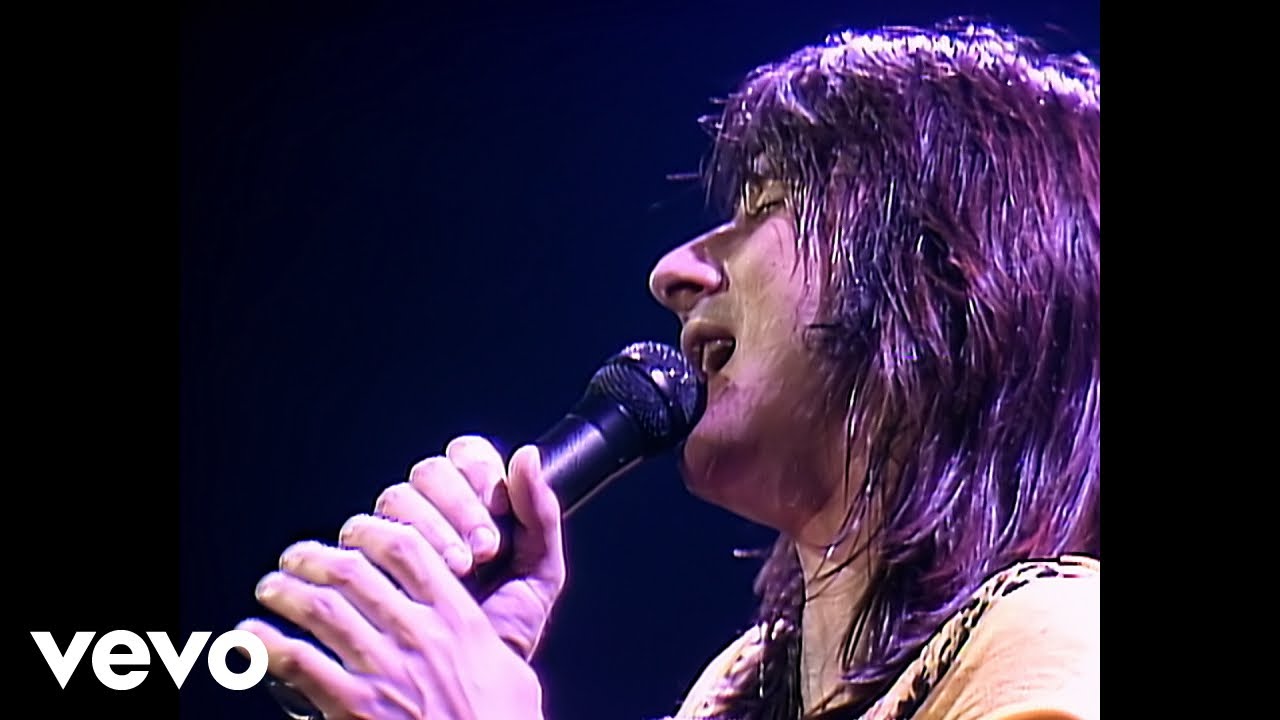

Steve Perry’s voice drops and quietens and he says slowly: “I was sitting in a studio doing the 5.1 surround sound mix for the DVD of the 1981 show in Houston. This would have been around 2005. I was watching that performance, and the audience reaction, and I literally had to stop the tape a few times.

“I didn’t recall it being that way because on stage I was in my own world, going song to song, trying to make sure I’ve got the consistent vocal strength needed, not wanting to blow out… and I found it very hard to look at the screen.

“I had to sit there with my head down. I never got on the outside before. I never watched the videos. The truth about my voice – I was ready for that. The truth about the audience response – that was something else. I did not hear that emotion until I was mixing it.”

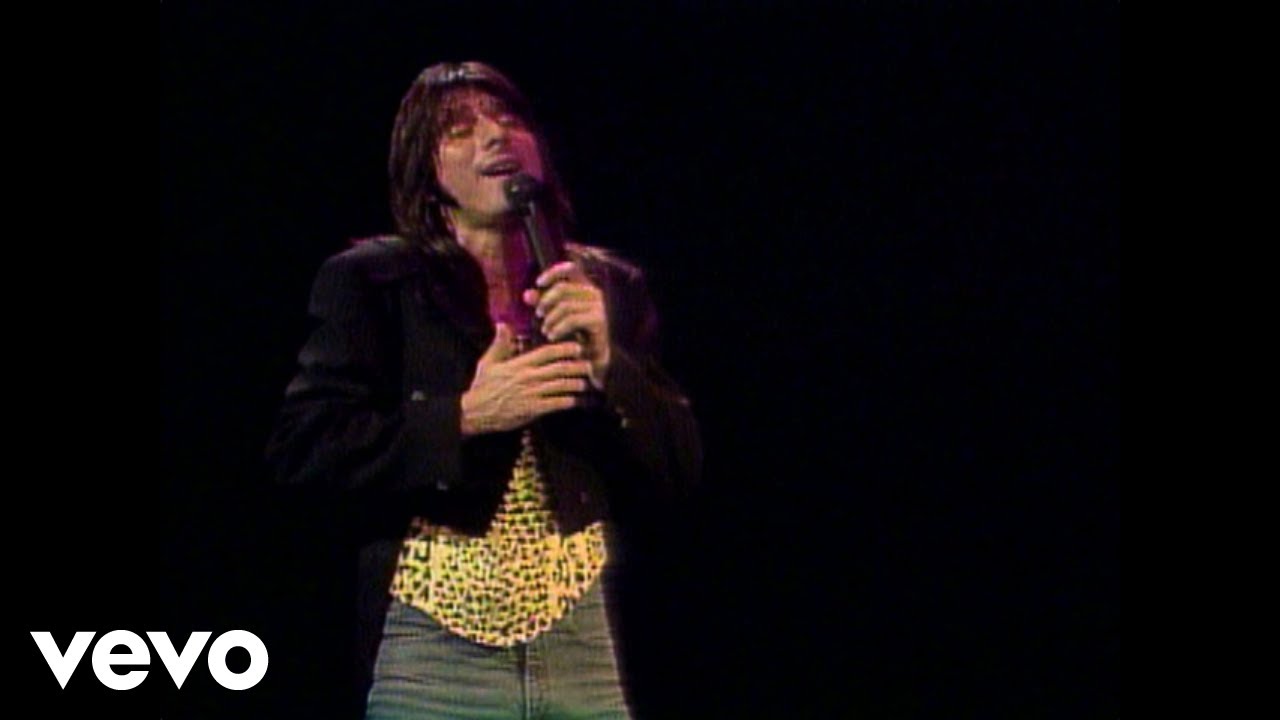

There’s a feeling about Steve Perry that he’s a man who’s been under siege for the past 20 years. It’s understandable. If Perry had made the best reggae album of all time, or the greatest soul album, even the top punk LP, he’d be fêted without question, the subject of fawning newspaper profiles and ass-kissing magazine retrospectives. But instead, he and Journey made the greatest AOR album of all time, and so he has been scorned by critics, omitted from all of those lists of great singers and best albums.

But all the while, Journey’s music has been out there, a soundtrack to ordinary lives, building up a fund of nostalgic goodwill that is now paying out.

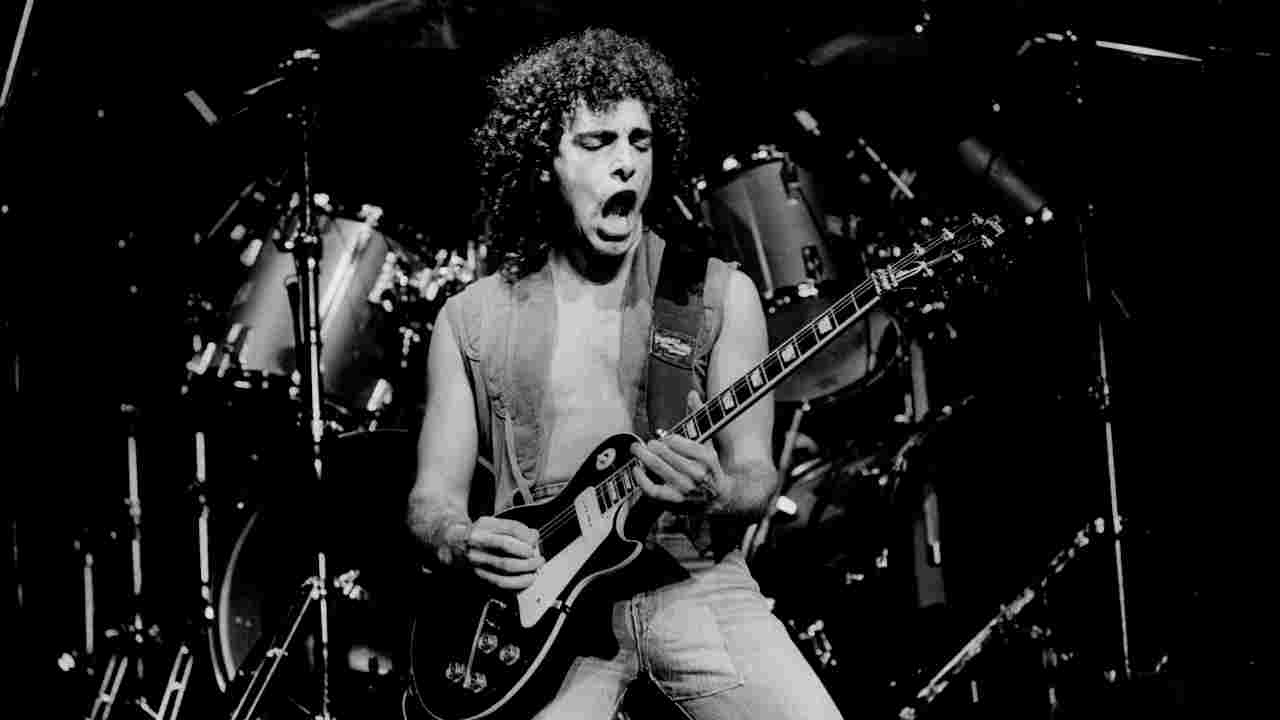

In a tremendously well-mannered delivery, but without a breath, Perry says: “I want you to know a couple of things, one of which is that the attacks and criticism on the band as being not viable and valid were vicious and, for me personally, I just got a whole bunch of fuck you, because I never cared. Because I was the one who agonised for me. Neal Schon agonised to get his parts as good as they would be. Steve Smith busted his ass. Ross Valory came up with bass lines to rival cello lines. Jonathan Cain came up with some of the most beautiful melodies, some of which were timeless.

“We were just doing the best we could do at the time. Time has shown that people condemned us, attacked us because we weren’t the hip of the hip. We held our course. Emotionally, it was sink or swim. I’d rather fail than be successful being somebody else. I couldn’t live with that. But I can live with failure if I fail on me. I think time has been so kind to us. Maybe we weren’t so fucking bad.”

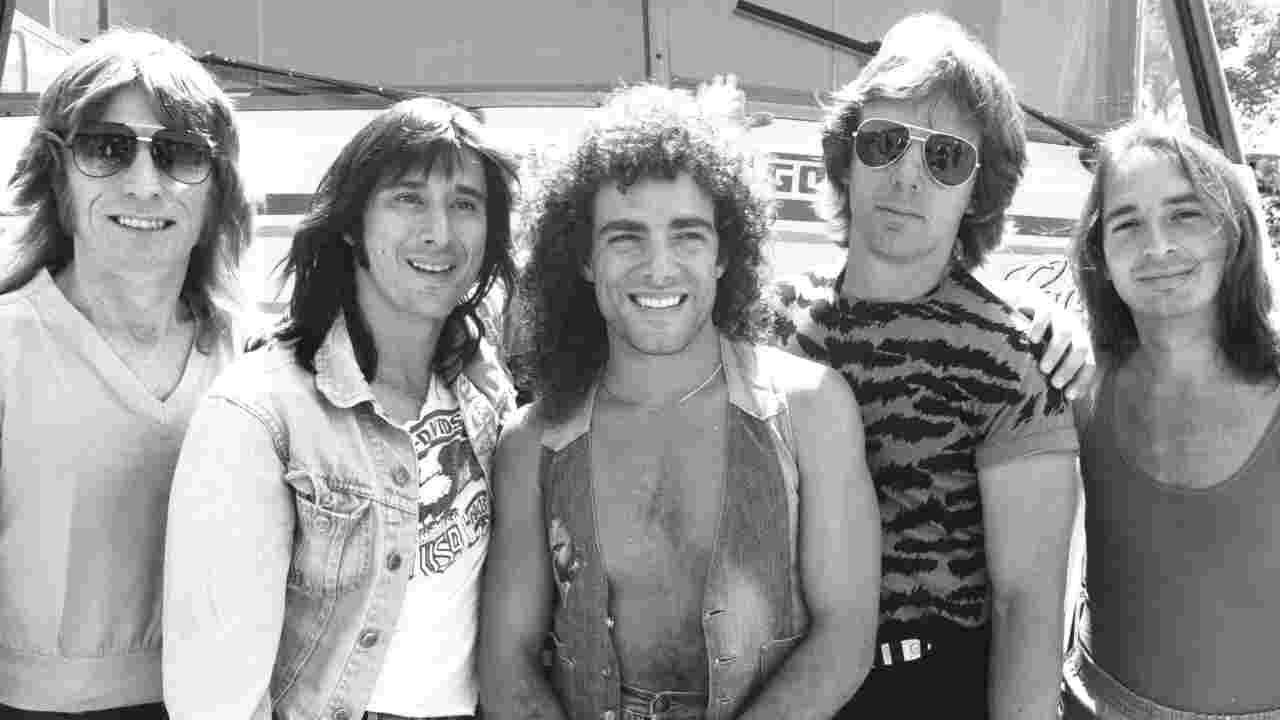

Steve Perry joined Journey in 1977, brought in by the band’s manager Herbie Herbert to shift its direction from rather musicianly jazz rock towards something more saleable. They cut three albums in three years, Infinity, Evolution and Departure, each better than the last.

“If it wasn’t for Herbie, I wouldn’t have been in that band,” says Perry. “When we accepted the Walk Of Fame star in Hollywood, I thanked him, although he wasn’t there – and in my heart I wished he was, even though we had our ups and downs – but I wished he was there because I told the crowd that if it wasn’t for Herbie, I would not have been in that band.

“It’s because he made a conscious decision when he heard my demo tape to convince the band that this is the guy. And they were not that convinced. They were looking for a different direction. They wanted a little more of a screamer, I was told. So they were tentative as to whether I was the right guy or not, and I think they were tentative for an album or two. And so there was always a bit of a feeling that I had to prove myself, that I was worthy of being in this band.

“Around Departure [1980], it started to get good. We started to get some hit records. And then when Jon Cain came in to replace Gregg Rolie, it leaped to that next level. With Jon coming in the band we made another change. Whenever you make one change you’re going to alter the recipe of the pie.”

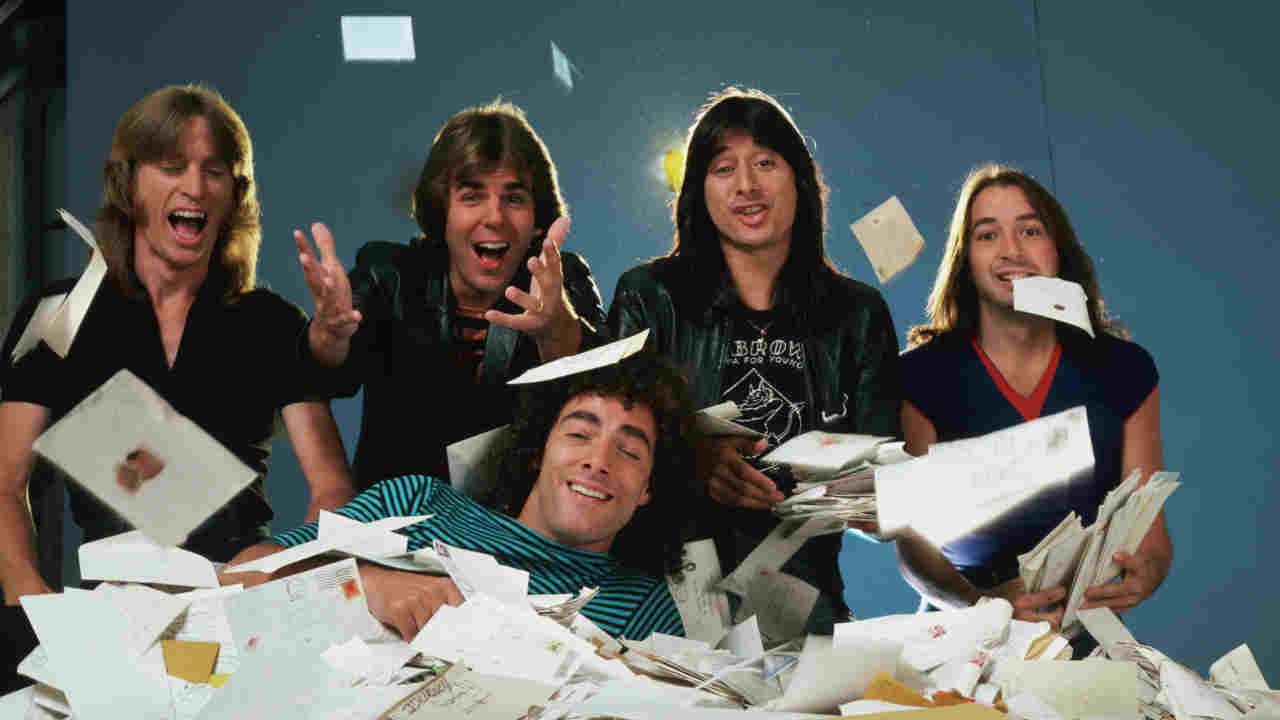

“I was in The Babys before Journey,” says Jonathan Cain, still smiling at his good luck. “We opened up for Journey just before I was hired and I used to watch them from the sidelines. I saw the talent that was there. I was ready. I’d done a couple of albums with The Babys and John Waite, who was the singer, he’d pretty much decided he was going solo, so Journey came along at the right time for me. John taught me a lot about the business. I was married by then to my first wife [the singer Tane Cain] and I knew I could write, so I finished the Babys tour, packed up my stuff and moved to California.”

Jonathan Cain was not joining a band run in the conventional fashion. Herbie Herbert had created Journey as a vehicle for Neal Schon, a guitar prodigy who was playing with Carlos Santana at the age of 15, and to whom Herbert had become something of a surrogate father. Perry and Cain represented substantial tweaks to the formula Herbie had in mind, and also to the internal politics of Journey.

“I had this grand plan that I presented to them before the Infinity album,” Herbert said in a 2002 interview. “I said: ‘Here’s the titles of all our albums, Infinity, Evolution, Departure, Captured, Escape, Frontiers and Freedom.’ When Gregg Rolie told me he was leaving, I said: ‘Gregg, how the fuck can I replace you? I want to shut this thing down.’ And Gregg said: ‘This kid that’s in the opening band…” I said: ‘Gregg, the fucking Babys stink!’ He said: ‘No man, watch him again… The kid’s got talent.’”

Steve Perry laughs in agreement as he is read the quote. “The band was built by Herbie around Neal Schon, so he could stand centre stage and be a prolific guitar player,” he says. “So when I joined, if there was any competiveness in a sibling rivalry-type way, it was that there was now this other guy who wanted to share the centre spotlight with the guitar player. Between Neal and I, that was a new rub that needed to be completely worked out and sometimes it did and sometimes it didn’t. That’s what bands do, and that’s what makes it work, by the way. I want to make that clear. The friction brings the heat.”

“When I joined, I was able to help put the pieces more solidly together,” says Cain. “I think I maybe oiled it and everything flowed better. It was that mix of different personalities, they had a kind of swagger to what they did that I really liked. Neal’s guitar playing was incredible. Perry’s voice was in its prime. Steve Smith and Ross Valory laid it down. They were a machine. After The Babys it felt like another level. I remember they had this rehearsal warehouse they used in Oakland, and the first time I went there, all of my gear was set up. I’d never had that before. The band sounded like a rocket taking off. I was just happy to be there, you know.

“Neal and Steve were quite different. Neal had a lot of rock’n’roll ideas that I would go through and maybe tweak a little and present them to Steve in a more nuanced way. Neal had a lot of unstructured melody in his head. I could sometimes add to those melodies and all of a sudden Steve would know what to do with them. I made suggestions that helped things click.”

“I’d never really known Jonathan Cain or met him,” says Steve Perry. “It didn’t matter much. What mattered was that we were in this band now together, not dissimilar to the way a baseball player gets traded from one team to another. You’re just glad that you’re on the team together. And it really did feel like we had a mission and that was the most important thing, to write great music and record great music and get it in front of people who would hopefully like it as much as we did.

“And so that began a creative courtship between Jonathan and myself and Neal that had never existed before. I remember being in Los Angeles when that tour was over and we were to start writing what was to be the Escape record. I remember just being full of anticipation because Jon and I were going to start writing together but we really didn’t know what we were going to write. On the way up, I had a little group of cassettes that I used to keep melodies on and I had this harmonic line that was basically…” – and at this point, the famous voice, apparently untouched by time, breaks into song – “‘One love feeds the fire, one heart burns desire, wonder who’s crying now…’”

“That was the first thing we wrote, first day,” remembers Cain. “I can’t remember exactly how long it took, but not long. Maybe an afternoon. I have to say the guy’s voice was incredible. He’d just stand there by my piano and out it came. He was amazingly consistent. We had an instant chemistry.”

“We wrote that up in an attic above a little room that Pat Morrow, who was our road manager, had. It was up in the Castro district of San Francisco,” recalls Perry. “At the time I was living in the Bay Area too and Jon came over to the house to write some more. He had a little Wurlitzer piano, and he was just messing around and he had this melody with his right hand…” – Perry sings again, this time the piano part that begins Open Arms – “and I was like: ‘What’s THAT?’ He said: ‘Oh, it’s an idea I started a long time ago for The Babys, but John Waite didn’t like it.’ I looked at Jon and I said: ‘You know what, Jon? Too bad for John Waite…’ And right on the spot I just sang that melody that he had on his right hand and it just came out: ‘Lying beside you, here in the dark…’ Then we wrote the chorus. We finished it there on that little Wurlitzer piano in my house. The music probably took a day, and then we tried to make the lyrics work, make them sing well.”

It was Cain who brought the framework of Escape’s most famous and enduring song, too.

“I had the title, Don’t Stop Believin’,” says Cain, “and the end piece and most of the lyrics. But it came together sitting there with Steve. We would arrange and refine. He had to have a lyric that worked for him as a sound as well as in its meaning. We worked very hard on that. We had the same sensibility, I guess. We both loved the radio and we wanted to hear our songs on it. We wanted to write songs that would get played over and over.”

“I think that it was probably emotionally not so comforting for Neal to see us writing together,” says Perry. “But then we wrote with Neal, too. The Don’t Stop Believin’ stuff, we all came up with together. There was a lot of stuff he was involved with co-writing. Stone In Love, with that great guitar riff, that one came from Neal.”

“Neal brought the fire and attitude,” says Cain. “I wasn’t conscious of just writing with Steve or just with Neal. It was about the three of us. Together we made it Journey.”

Escape is an album of moments, each of them marking out the songs, equipping them for history: Schon’s guitar break at the end of Who’s Crying Now; Cain’s intro to Don’t Stop Believin’; Perry’s phrasing of ‘Just a smalltown girl…’ or ‘Somewhere in the niiiight’. All are instantly identifiable, and the record is full of them. Schon’s instinctive playing, Perry’s attention to detail, Cain’s craftsmanship, each played their part in its impact.

“I had my moments where I was probably a bit of a stick in the mud for what I believed in, yes,” says Perry. “I never would settle. I know what I can do. There were certain things that I wanted a specific way. So I had to go back and keep trying to do them until I could find the way. One that comes to mind would be the vowel on Open Arms, on the ‘A’ of the chorus. I wanted it to sound a certain fucking way. I wanted it to happen, and I kept re-punching that for a couple of days until I got what I wanted. The same thing happened with Don’t Stop Believin’. I wanted a high note. It wasn’t as crucial as it was on Open Arms, I just wanted that long note to be something really special. I don’t want it to be even a nano-fraction out of pitch. That’s just how obsessed I could be. I’m cranky that way.”

Perry’s obsession extended through the spring of 1981 at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, where Escape was produced by Kevin Elson and Mike Stone, and on through mastering with Bob Ludwig in New York. His memory for the detail of the process is astonishing, extending right down to the type of vinyl used on the original pressing.

Escape was released at the end of July 1981, and at first it followed the usual trajectory of the big hit record: No.1 on the Billboard album chart, four hit singles, sell-out tour. The momentum kept Journey running through its follow-up, Frontiers (1983), another huge hit, and Raised On Radio (1986), which is Perry’s personal masterpiece, if not Journey’s. Then came the fall-out, and the extraordinary afterlife of the songs from Escape.

“I will tell you when I got it, and you’re going to think this is crazy, but it didn’t happen for me until I quit the band,” says Perry. “I finally told Jon and Neal: ‘I just can’t keep going any more, I just gotta stop.’ It was after the Raised On Radio tour. In the middle of making that record my mother had passed away. She’d been ill for quite some time, and I came back and finished the record, went on tour and I was toast. It was just a long run from the very beginning, 1978 to that point.

“The manager would put us out there where we were on three, four, five nights in a row, it was a blistering requirement, and my personal life with my ex was over – just a lot had crashed and I had to stop. For the first eight to 10 months I could not listen to music. I was kind of musically damaged. It just reminded me of too much emotionally, and I was concerned that I’d lost my joy and love for music. I guess I’d just worked very hard … they call it roadburn.

“I didn’t listen to any music for almost a year and then one time I heard a Journey song. Only The Young came on the radio, and I’d never heard it like that before. I heard it standing outside of the forest looking at the trees. That was emotionally tough. I didn’t know we were that good.”

“How did Escape affect me?” says Jonathan Cain ruefully. “Well, I got divorced, Steve broke up with Sherrie [Swafford, Perry’s then-girlfriend], families started having an impact, people wanted to do different things. Frontiers was great – I call Escape and Frontiers ‘the twins’. But it became all-consuming. It couldn’t sustain.”

There was one not-so-successful reunion album, 1996’s Trial By Fire, and a tour that was abandoned after Perry sustained a serious hip injury. In May 1998 Steve Perry was legally released from his obligations to Journey [the letter informing him of the fact remains pinned to the wall of the studio at his home]. In the same year a Greatest Hits package that would go on to sell 15 million copies was released. Journey’s place in history seemed set. They were a kitsch throwback, a lightly-regarded footnote. Schon and Cain reconstituted the band and ran through a parade of singers before settling on their latest, Filipino Arnel Pineda, who was discovered singing on YouTube.

And then, as the generation whose youth had been soundtracked by Journey’s songs became influential in the culture, something remarkable began to happen. In 2005, the Chicago White Sox won the World Series of baseball and adopted Don’t Stop Believin’ as their theme song. Steve Perry ended up on the field with them lifting the trophy. Reality TV took hold, and Open Arms became a staple tune for contestants on American Idol [a show judged by Randy Jackson, who had played bass for Journey on the Raised On Radio tour]. Don’t Stop Believin’ appeared in the films The Wedding Singer, Monster and Shrek and on the TV shows Family Guy and My Name Is Earl. In 2007, it was the song played at the climax of The Sopranos’ final show, its significance poured over by the critical community that had shunned it for so long.

By the time a cover by the cast of Glee went to the top of the charts around the world, it had become the most downloaded catalogue song of all time on iTunes. Journey and Steve Perry have now sold more records apart than they did while they were together. It is a strange but satisfying form of redemption.

“At some point those songs crossed over,” says Perry. “My understanding of The Sopranos is that David Chase [the show’s creator] burned a CD and told his writers: ‘This is the closing song.’ They used it as a template emotionally to make it work. When I saw the ending I actually jumped out of my chair and yelled at the screen. It was perfect.

“I stay away from the covers. I just want to keep the definitive versions in my mind and my heart. I don’t have any negative feeling about people doing them, and I’m grateful that they feel that emotionally they can do them, and if people can get a record deal or have a career in the music business, then I’m honoured that they choose them that way, but I choose just to not listen to other versions. I want to keep that original clean in my head.”

“The songs have lasted somehow,” agrees Jonathan Cain. “We left sort of an imprint. The songs are bigger than we are.”

Steve Perry’s life is today is a quiet one. “I don’t get out much,” he says. “I’m not one of those people who needs to be seen in public places.”

He admits that he has been left a little lost by the changes in the music industry. He has no record deal and no manager, and although there’s little doubt he could find both overnight, is unsure if he wants them.

Talking about Escape enthuses him, he says, as we speak after the interview that it has made him feel like doing something again, and a recent trip to a studio in Los Angeles had a similar effect – and yet he’s conscious too of the emotional cost that renewed exposure to it all might bring. It’s evident from his own words, and those of others, that he is not the easiest person to work with. He is a sensitive perfectionist, fragile, driven, unwilling to compromise on what he sees as the non-negotiables of his art.

Yet all of those qualities have a considerable upside. They led to the creation of Journey’s defining triumvirate of albums, to the songs that have endured and prospered for so long. His former bandmates seem to have accepted the fact too – their latest singer, Arnel Pineda, both looks and sounds like Perry.

“I just don’t want to disappoint people,” Perry says. “I hate expectation, because it’s impossible for people to live up to that. But that was always the case album to album. We were only ever as big as our last hit. What are you gonna do? You just write some music and hope for the best. It’s as good a strategy as any.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents AOR issue 1, August 2010