Don't Stop Believin'

Stone in Love

Who's Crying Now

Keep On Runnin'

Still They Ride"

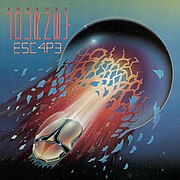

Escape

Lay It Down

Dead or Alive

Mother, Father

Open Arms

Almost every album that comes to define its genre feels in a way like it has always existed. It coalesces various elements – a sound, a feeling, a particular moment in time – and makes them solid. Think of Nevermind or Appetite For Destruction or The Dark Side Of The Moon, and they seem to hold within them the seeds of what the genre is and where it might go.

It’s the same with Escape. You can argue forever as to whether it is AOR’s greatest album, or even if it’s Journey’s best (Raised On Radio is superior in many ways), but it is inarguably the genre’s defining record. Its grip on the culture has grown stronger through the years.

From the moment that Don’t Stop Believin’ was used as the final piece of music in The Sopranos to the endless cover versions of Open Arms on American TV talent shows, Escape has become a piece of music that Jonathan Cain said “has lasted somehow. The songs are bigger than we are.”

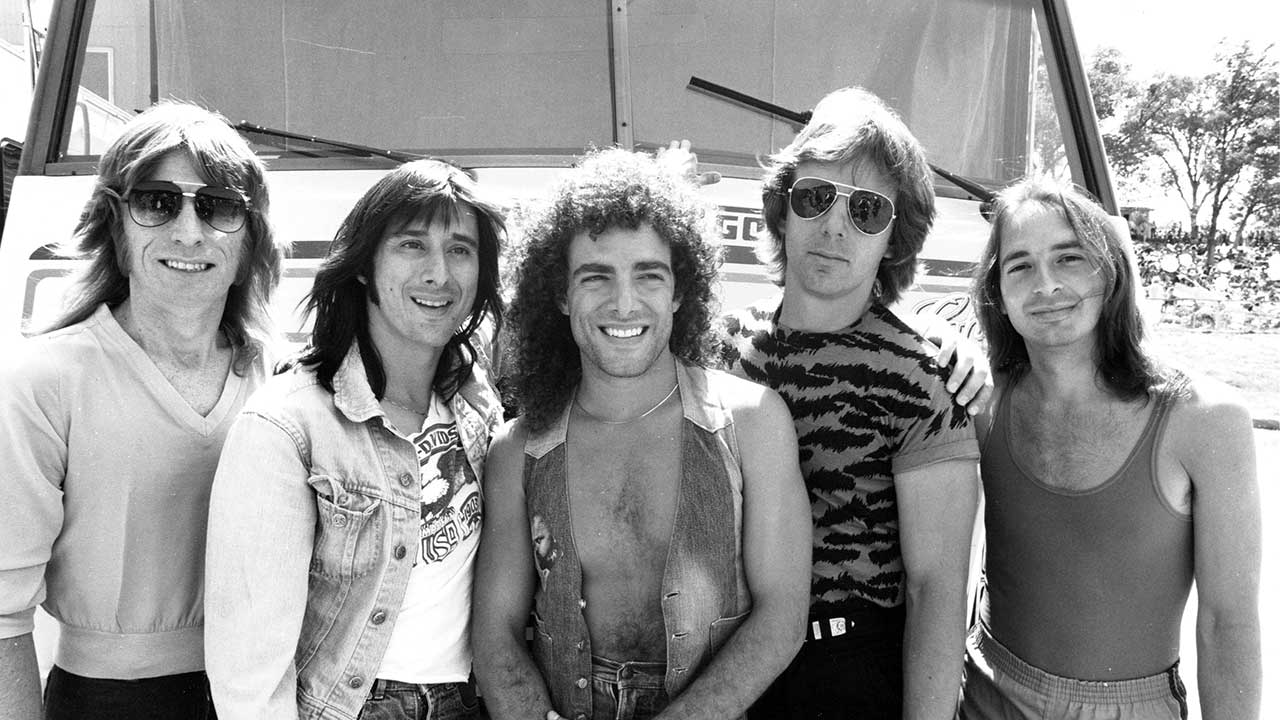

Cain, formerly of The Babys, was Journey’s missing piece. When he replaced Greg Rolie, the band left behind their vestigial jazz-rock leanings and refocused on the songs. For a record as apparently seamless as Escape, Journey were an interesting factional mix, cliquey and at times suspicious of one another.

They were held together by the force of personality of Herbie Herbert, the manager who had brought Steve Perry to the group almost four years before. Ever since, Perry had been engaged in a battle for the spotlight with Neal Schon, around whose guitar playing Journey had originally been built. The addition of Cain, who quickly fell into a writing partnership with Perry, increased the creative tension: “The friction brings the heat,” as Perry described it.

“When I joined,” Cain said, “I was able to help put the pieces more solidly together. “I think I maybe oiled it and everything flowed better. It was that mix of different personalities – they had a kind of swagger to what they did that I really liked. Neal’s guitar playing was incredible. Perry’s voice was in its prime. Steve Smith and Ross Valory laid it down. They were a machine.

"I remember they had this rehearsal warehouse they used in Oakland, and the first time I went there all of my gear was set up. I’d never had that before. The band sounded like a rocket taking off.”

Cain was a conduit between Schon and Perry. “Neal had a lot of rock’n’roll ideas that I would go through and maybe tweak a little and present them to Steve in a more nuanced way. Neal had a lot of unstructured melody in his head. I could sometimes add to those melodies and all of a sudden Steve would know what to do with them.”

On their first day of writing together, in the attic of their road manager’s apartment in San Francisco, Perry played the melody for Who’s Crying Now on a cassette he’d been storing his ideas on, and within an afternoon the song was written.

“We had an instant chemistry,” said Cain. At Perry’s house they came up with Open Arms from a piano part that John Waite had rejected for The Babys.

“Too bad for John Waite,” Perry remarked after hearing it.

“I think it was probably emotionally not so comforting for Neal to see us writing together,” says Perry. “But then we wrote with Neal, too. The Don’t Stop Believin’ stuff we all came up with together. There was a lot of stuff he was involved with co-writing – Stone In Love, with that great guitar riff, that one came from Neal.”

“Neal brought the fire and attitude,” Cain said. “I wasn’t conscious of just writing with Steve or just with Neal. It was about the three of us. Together we made it Journey.”

Journey rode their creative high, yet even the most cursory listen to Escape reveals the aural perfectionism that Perry in particular obsessed over. They were all sound freaks, none more so than the singer, whose knowledge of recording techniques and reproduction were matched only by his desire to get down on tape the things he was hearing in his head.

He recalled spending two days in the studio getting the right ‘A’ sound on the ‘arms’ line of Open Arms, and trying to keep his spectacular longer notes on Don’t Stop Believin’ exactly in tune.

Perry dictated the type of vinyl used for the first pressings of the record, which came out in July 1981, just two weeks after Foreigner’s 4. Tied by serendipity, those two albums would produce AOR’s high-water mark.

Journey were touring America by private plane and selling out football stadiums years before Bon Jovi and Guns N’ Roses surfed the same wave, and they encountered all of the same rock-star strains and excesses. I once asked Jonathan Cain how Escape had affected them.

“Well,” he said, “I got divorced, Steve broke up with Sherrie [Swafford, the Sherrie of Oh Sherrie], families started having an impact, people wanted to do different things. Frontiers [released 20 months later] was great – I call Escape and Frontiers ‘the twins’. But it became all-consuming. It couldn’t sustain.”

History has been kind to Escape. As far back as 1988 the readers of Kerrang! voted it AOR’s greatest album, and there it remains, probably in perpetuity. But beyond the confines of genre it has enjoyed an afterlife bathed in nostalgia for the version of American youth that it captured, a time long gone except in the memory.

There, Escape lives.