Just over 30 seconds into Steven Wilson’s new album To The Bone, there’s a squall of harmonica. It’s one of the many meticulous details that has made Wilson the undisputed leader of his gang. But this is not any old harmonica squall. It’s the playing of Mark Feltham, the man who did similar on Talk Talk’s three greatest albums, The Colour Of Spring, Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock. Released in 1986, ’88 and ’91, these records were undoubtedly prog – in the truest sense of progressive music.

Wilson has located this 80s prog succinctly on To The Bone, making a record that sounds like the sum of its influences – Talk Talk, Kate Bush, So-era Peter Gabriel and, most importantly, Tears For Fears. These were the artists who, aside from Gabriel, had no visible prog past, but were adept at wearing their influences on their sleeves in a manner far more concomitant with the glossy yuppie decade than the standard-bearers for prog in those years, such as Marillion and IQ, who were unashamedly emulating their heroes.

As Wilson says, these were records “mainly made by musicians who’d come out of the crucible of innovative, experimental 70s music but still wanted to write great songs that people could hum on the bus. They’re unapologetically accessible but with not even the slightest sense of dumbing down. They have a huge sense of ambition.”

But it wasn’t just these artists that were carrying a flag for the genre and had huge ambition in this most debated decade. David Sylvian and The Blue Nile, for example, were both at it. Smuggling it into the very upper echelons of the UK charts and onto Top Of The Pops were Nik Kershaw and Howard Jones. In fact, a great deal of pop was masterminded by Trevor Horn, a man who had been in Yes. What was the title track of Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Welcome To The Pleasuredome, if not a side-long prog opus, featuring Steve Howe on acoustic guitar?

Wilson has also collaborated with XTC’s Andy Partridge on To The Bone, and lest we forget, XTC’s strong art pop took a distinctly pastoral prog turn with the double album (a double album, you say!) English Settlement in 1982. These artists weren’t burying their passion for prog, and were less concerned about masking their influences and record collection than those who had fought in the punk wars.

While Genesis became stadium-filling pop rockers, Yes became arty AOR, Rush morphed into a heavier version of The Police and King Crimson became an artier Talking Heads (if that could be possible), one old progger stuck to his guns and brought his difficult music into the higher echelons of the charts. Peter Gabriel led the charge and set the template that he had begun right back on Selling England By The Pound with Genesis in 1973: make sure you put a hit single on it, and then you can make the rest as weird as you like. His old Bee Gees/Otis Redding obsession rang through and each of his albums contained either a chart smash or radio track.

This came into sharpest relief by the time of Security (as no one in the UK called it Peter Gabriel ‘4’) and So, where there was simply abject weirdness coursing through the albums but people purchased in droves. This had started with Games Without Frontiers on his Melt (or ‘3’) from 1980, and Shock The Monkey on Security. By the time of So, he could get away with We Do What We’re Told (Milgram’s 37) and This Is the Picture (Excellent Birds) – resolutely not AOR staples – because he also had Sledgehammer and Don’t Give Up.

Gabriel’s influence undoubtedly shaped this 80s ‘prognotprog’, although his duet partner on Don’t Give Up, Kate Bush, had long broken through. David Gilmour was an early champion, while her albums The Kick Inside and Lionheart were both highly successful releases working on broadly surreal adaptations of a Carole King/Joni Mitchell template.

However, she met Gabriel in 1979 and became an eager pupil of his. Her work can be viewed as pre- and post- contributing to Gabriel’s third album in early 1980. Using Fairlight technology, Never For Ever from later that year contained Breathing – about a foetus singing in its mother’s womb, concerned about nuclear fallout – and took a distinctly art prog turn.

This new direction was completely confirmed by 1982’s The Dreaming, an album ultimately so way out that its big, bold themes (Vietnam, Aboriginal plight) proved unpalatable commercially (yet it still got to No.3 in the UK charts). But in 1985, she did it all over again, and followed Gabriel’s golden rule of packing the hit singles. Hounds Of Love can be viewed as her ultimate album, and a flag-waver for ‘prognotprog’.

The first side contained four thumping great left-field singles (Running Up That Hill, Cloudbusting, Hounds Of Love and The Big Sky), and then the second side went off the scale in its weirdness. It’s so unusual and singular, it could easily have been released on the Vertigo label in 1971 and now be worth £400.

The Ninth Wave was a seven-track suite about someone adrift at sea, trying to stop themselves drowning by running through their life. “I love the sea,” Bush told Kris Needs at ZigZag in 1985. “It’s the energy that’s so attractive – the fact that it’s so huge. And war films, where people would come off the ship and be stuck in the water with no sense of where they were or of time, like sensory deprivation. It’s got to be ultimately terrifying.”

With choral interludes and Irish jigs, it’s a fully functioning foible that chimed with the new CD generation. It was clearly one of Bush’s favourites because when she made her return to the live stage in 2014 with her Before The Dawn concert series, The Ninth Wave took up the first half of the show.

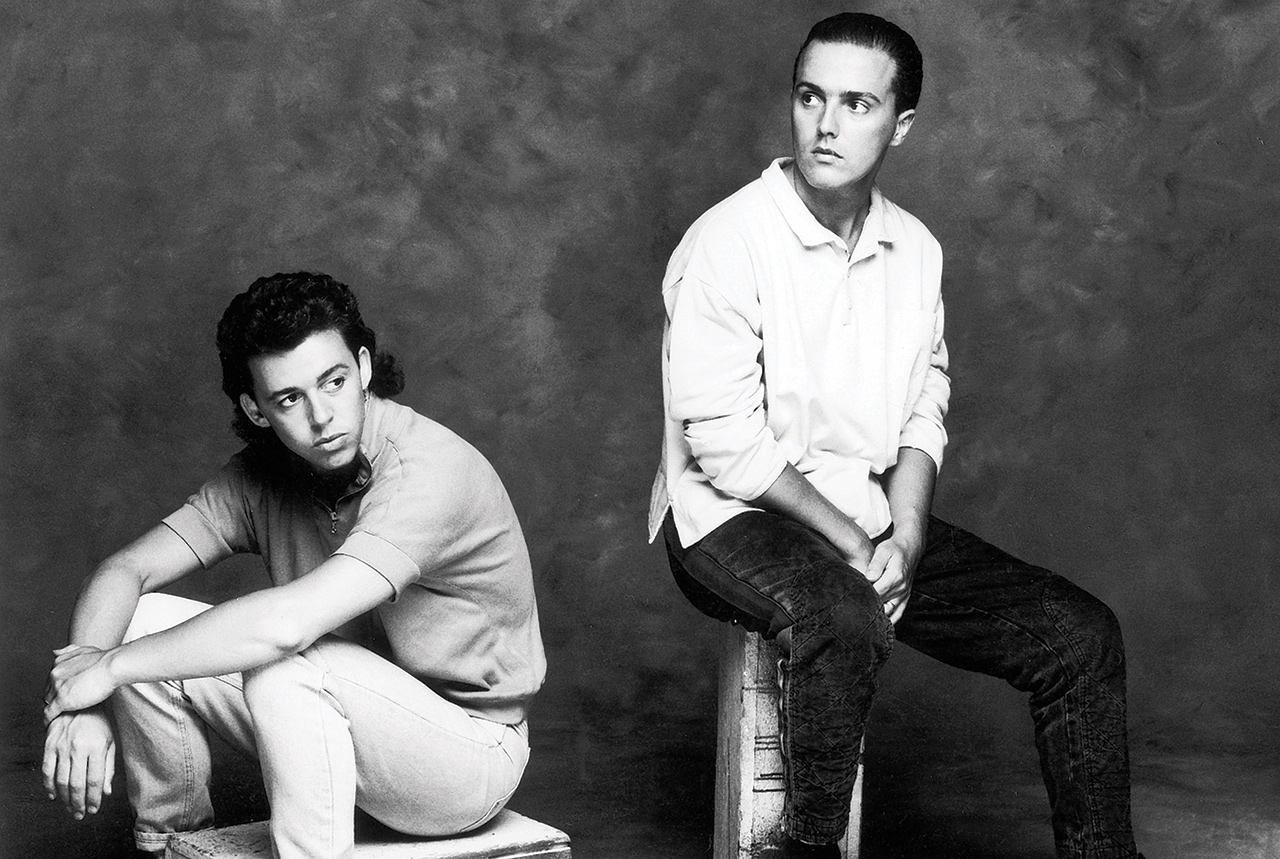

Influenced by both Gabriel and Bush, the work of Tears For Fears courses through To The Bone. Although Curt Smith and Roland Orzabal had been in 2 Tone-aping band Graduate (their near-hit Elvis Should Play Ska is forever on the Prog office playlist), they were spotted quite clearly in the audience at the Discipline (the band that became King Crimson Mk IV) gig in Bath’s Moles club in April 1981. They worked with Gabriel’s producer David Lord and shared engineers and players with both ‘Bath Peters’ (Gabriel and Hammill). Had 1985’s Songs From The Big Chair – its second side especially – been released a decade earlier, it would have been a greatcoated common room masterpiece.

Taking its title from the TV film Sybil, about a woman with a multiple personality disorder who only felt safe in the psychiatrist’s chair, Songs From The Big Chair contained big, deep, intelligent music and showed that newcomers could experiment as strongly as any who had gone before. It was clear from the start that Tears were troubled souls who wore their influences on their sleeves, and for every commercial ditty, there was an experimental depth charge.

“Obviously we’re trying to get away from the three- or four-minute pop song, but that doesn’t mean 24-minute concept pieces at all,” Orzabal told Melody Maker in 1983. “A couple of things on the album [their debut, The Hurting] totally got away from the pop song, namely The Prisoner and Ideas As Opiates. The Prisoner isn’t even a song really, it’s just a collection of motifs. But the three-minute, four-minute, five-minute pop song… it’s good to have a framework to build around.”

And they never forgot that framework – hence Everybody Wants To Rule The World and Shout, allowing Listen, Broken and The Working Hour to be accepted by the masses as there would be a hit coming along in a few minutes.

Prog’s own Chris Roberts, writing for Uncut in 2001, said, “If Tears For Fears fell between two stools as teen pin-ups wanting to be serious art musos, they still pulled off phenomenal commercial success with records that remain unembarrassing.”

There’s nothing remotely embarrassing about the accessibility of the pop hits on Songs From The Big Chair, which made it such an enormous seller – Shout, for example, was No.1 in 10 countries. But then you also have Listen, which closes the album: seven minutes of ambient jazz that ends in a sub-African chant.

There were certainly others who could wear the 80s ‘prognotprog’ label: David Sylvian fused prog with kosmische on Brilliant Trees and the double Gone To Earth, the second disc of which was an ambient album featuring Bill Nelson and Robert Fripp.

The Blue Nile defy categorisation, but they were clearly the ones that were played by most artists in their own collections. Leader Paul Buchanan’s other-worldly pleading, keening voice is one of the most recognisable yet completely located in its own bubble, dropping oblique lines such as: ‘I write a new book every day, a love theme for the wilderness.’

Their 1984 album A Walk Across The Rooftops remains one of the best-kept secrets within popular music. From Rags To Riches on the album is typical of this adult, genreless music. What is it? You’re simply not sure, but it clearly owes a great deal to the strangeness of the instrumental passages of their forebears [You’re not telling me Marillion haven’t heard the title track! – Ed]. Both Howard Jones and Nik Kershaw were multi-instrumentalist writers with proper muso pasts who were in the Top 10 in 1983 and beyond. Jones came out of the Aylesbury scene, made his name in Friars and was managed by David Stopps, who’d been so instrumental in promoting progressive rock a decade previously. Jones had a mime artist with a painted face (Jed Hoile) and a debut hit (New Song) that evoked Peter Gabriel’s Solsbury Hill. New pop? Old prog, more like!

However, to these ears, it come backs to where we began, with Mark Feltham’s harmonica squall that opens Steven Wilson’s To The Bone. Talk Talk’s The Colour Of Spring and Spirit Of Eden are arguably the prog albums of the 80s, although leader Mark Hollis would be the least likely to suggest that. Few travelled from their initial incarnations into something deeper, darker and stranger than did Talk Talk.

Hollis was steeped in music – his elder brother Ed had been a DJ and the manager of Eddie And The Hot Rods. Ed lived in a static caravan packed with albums and was known as ‘1000 Eddie’ for his incredibly diverse and sizable record collection, and it was clear that Hollis spent a lot of time gaining influences from it.

Although Hollis had started in a new wave/mod band called The Reaction, in 1978, by the turn of the decade, he’d hooked up with Paul Webb and Lee Harris (and, initially, Simon Brenner), signed to EMI and Talk Talk at once seemed liked a Duran Duran-lite. They supported Genesis at their legendary, sodden Gabriel-saving Six Of The Best concert at Milton Keynes Bowl in October 1982, where they, shall we say, received a less than enthusiastic response. Hollis didn’t care about the charts or what Genesis fans thought – he was whip-smart and by now had started listening to John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and he brought their improvisational nature to his band.

Now writing with producer Tim Friese-Greene, their second collaboration The Colour Of Spring contained the hit single Life’s What You Make It. With its Can-like intense repetition, it was an entrancing work that gave Hollis the green light to experiment further, the result of which was 1988’s Spirit Of Eden, an album of six long pieces that was all about mood, as opposed to commercialism. With its jarring blasts of guitar, few obvious melodies, alternating between soft and screaming, it was an enormous commercial disappointment on release, but now, quietly, is one of the most-loved records of its era – a true mark (no pun intended) of quality.

By celebrating records such as this on To The Bone, Steven Wilson lays to rest the hoary old chestnut that prog was killed off in 1976 as soon as the Sex Pistols appeared on the Today show. In the 80s, it got smart and absorbed many different influences. This led to some extremely difficult tracks being smuggled into CD collections, but that was OK, because there were also, as Steven Wilson says, plenty of “great songs that people could hum on the bus”.