“We played Madison Square Garden twice in one day… we saw our name in 50ft-high letters and said, ‘Perhaps we’ve made it!’ We bought a load of tickets off a scalper and gave them away”: When the Moody Blues started taking themselves seriously

Justin Hayward and co weren’t sure how long they’d last after inheriting the music of Denny Laine - but they needn’t have worried

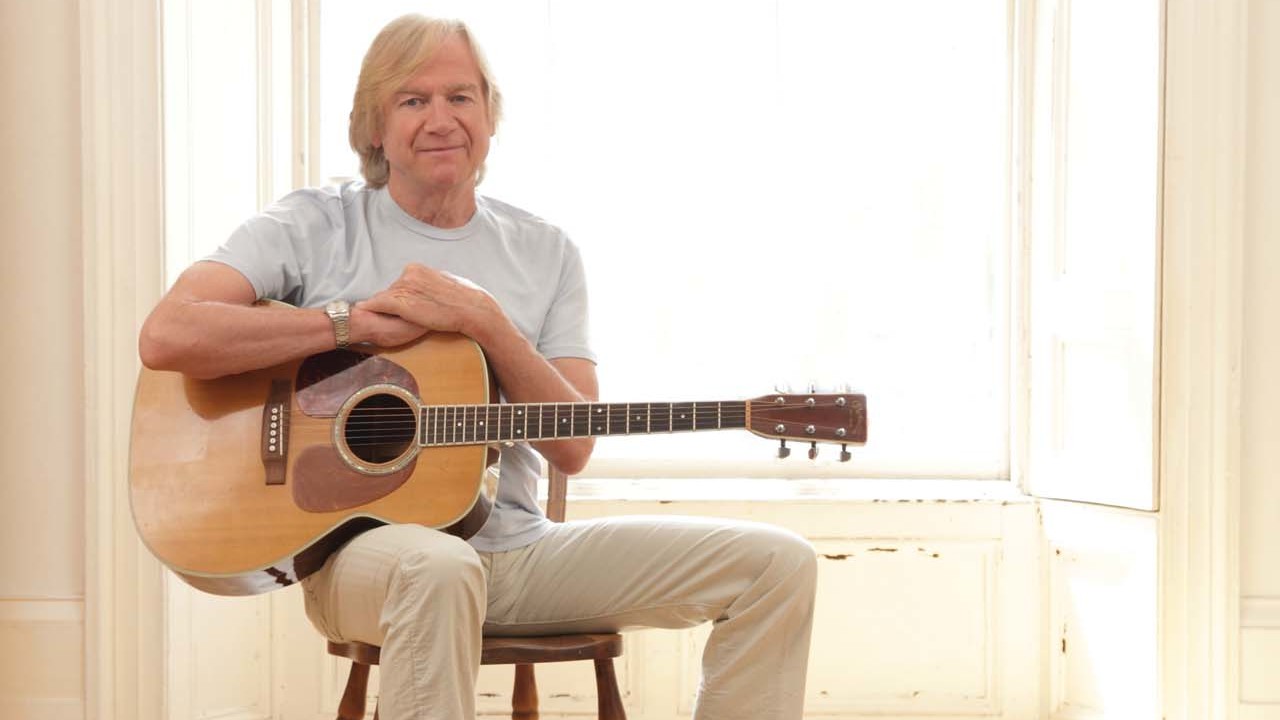

Justin Hayward has had a long and successful career since joining The Moody Blues in 1966. Through songs like Nights In White Satin, he’s established himself as one of the most erudite and copied composers of the last five decades.

But Hayward’s impact has gone beyond his tenure with the Moodies. The Swindon-born musician has also had an acclaimed solo career, as well as working with fellow Moodies member John Lodge on the album Blue Jays. And let’s not forget that prior to being recruited by The Moody Blues, a teenage Hayward had already signed a publishing deal with skiffle king Lonnie Donegan, and in 1965 he was hired by British pop star Marty Wilde to join his backing band. It was from there he made the jump to the Moodies. But let’s not forget when he became a member, the band were a fading R&B act. Together with fellow new recruit Lodge, he helped to turn things around and put The Moody Blues firmly on the path to becoming the icons they are today.

He also found wider fame through the hit single Forever Autumn on the original recording of The War Of The Worlds in 1978, and even spent time onstage in the touring production of the Jeff Wayne musical. Yet, despite all this high profile attention, Hayward has retained his privacy, and it’s something he’s strongly protected. All of this makes it surprising that he was the subject of TV show This Is Your Life in 1997. But what this did was accentuate his widespread appeal, proving to everyone that he’s well known in the mainstream, as well as being a pioneer in the progressive world with the Moodies, who’ve long been renowned for the way they helped to develop symphonic rock.

Yet despite his high profile, little is known about the real man. For instance, where did his love for music begin, and what made him want to become a musician in the first place? And how does he feel knowing, despite being eligible for inclusion since 1989, the Moodies have been constantly overlooked for the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame? In 2017 he gave Prog an insight into who Justin Hayward is, and what inspires him to this day.

Was there a moment when you knew you wanted to be a musician?

I got my first guitar when I was 10, and I hustled a few kids at school to get a group together. I recall how much I loved all of us being in someone’s front room, trying to work out the chords to some songs. It probably included Rock Around The Clock. And then when I heard Buddy Holly for the first time, that brought everything into focus. I knew what I wanted to do.

When you were a child, were you a natural performer?

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

No, I was never like that. And I’m still not what you would call a performer. For me, it’s all about the songs, and they open the door. I’m part of constructing and presenting them, but I am always hiding behind these as well.

Who were your musical heroes growing up?

Elvis was the king. When he came along, I must have been eight or nine. But Buddy Holly was the one for me. I was lucky to get to America in 1968, less than 10 years after he died, and was able to visit places like Lubbock, Texas, where he was born. The Everly Brothers were also a massive influence, because they got me interested in vocal harmonies. I was so pleased to be able to spend some time with Phil Everly some years ago. That memory’s precious to me now that he’s gone.

Was there one record that changed your life?

It would have to be Love Me Do from The Beatles. This was when I was still living in Swindon, and I recall thinking that something very different had just happened. I do remember seeing Steve Race, a jazz pianist who seemed to be on every music programme at the time, appearing on a TV show and saying The Beatles would never last. I thought he was a deeply unpleasant man after that. You have to be very careful what you say about other musicians! That was a good lesson for me at the time.

When you joined The Moody Blues in 1966, did you think it would last?

I don’t think any of us did. We were all trying not to do a proper job. At first, we were really doing another band’s act. Because the music belonged to [departed guitarist/vocalist] Denny Laine, and I don’t think any of us had our hearts in it until we began to do our own songs. Once that happened, then things began to change. But until then, nobody thought the band could last long.

The Moodies have been hugely successful, but remained almost anonymous. Was that deliberate?

For us, the music has always been the star. None of us wanted to be personalities or celebrities. We’ve gone out of our way to avoid that sort of thing. We never had a press agent in our early days. Quite early on, we got a little burned by the press, so we stayed away from that side of things.

When did you realise how successful the band had become?

It look a long time for this to hit me. I think it was in 1973, when we played Madison Square Garden twice in one day. Between the shows, Ray Thomas and I went for a walk and we saw our name in 50ft high letters in the square, and we said to each other, “Perhaps we’ve made it!” We also bought a load of tickets off a scalper and gave them away. They had no idea who we were!

Do you ever find your mind drifting onstage when you’re doing a song you’ve done countless times before?

I do with the Moodies, because there’s time to do that. But when I’m doing a solo show, I never do it, I always stay in the moment, because the musicians I’m with are so good that I want to keep up with them. Of course, I love playing with the Moodies, but there’s a real joy for me in doing solo dates.

Does it bother you that The Moody Blues continue to be ignored by the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame?

Not at all. For me, it’s irrelevant. I know some of our American fans are upset about the situation, but for us it means nothing. This band doesn’t feel we need that sort of award to validate what we do. We’re too busy getting on with our lives and careers to care. If a couple of guys had died in the mid-70s, then we’d probably have been inducted into the Hall Of Fame. We’re guilty of being boring and staying alive though.

You have done projects away from the Moodies such as The War Of The Worlds album. Do you wish you’d done more of that type of project?

Yes, I do. I’ve done a few. Some have been successful, others haven’t. Forever Autumn from The War Of The Worlds was the big one for me, and I was lucky enough to do the stage show for four or five years as well.

What does Forever Autumn mean to you?

I feel blessed to have been the one chosen to do the original version. It has a poignancy to it, and any time I play it live, people really get into it. It has been a great gift for me.

What made you want to work with Jeff Wayne?

He sent me a demo of the song, and was certain I was the person he wanted to sing it. I played it a couple of times, but wasn’t sure it was right for me. But that day, there was a young lad at my house, who worked in Threshold Records, The Moody Blues record shop in Cobham. He came into the lounge while I was playing, and when it finished he said, “You ought to do that song. It’s perfect for you.” So that convinced me to try it. I wasn’t up to anything at the time, so went down to Advision Studios in Central London, met Jeff, and you know what the first thing he asked me was? “Are you the guy who sang Nights In White Satin?” Just to be sure he had the right person!

You mentioned Nights In White Satin: what do you think makes it such a classic?

I often ask myself why it’s so popular. Even after we’d recorded it, people were saying it was too slow and too long to be a hit single. So when it happened, I was taken by surprise as much as anyone! It was a song I wrote one night, sitting on my bed. I took it in the next day and played it to the other guys, and they were a bit nonplussed by it. Mike Pinder then told me to play it again, and added in a Mellotron part, and somehow it made everything work. But as to why it’s loved by so many… I haven’t a clue!

What is your all-time favourite Moodies song?

I like the things we did with Tony Visconti. Those are my favourites. And top of my list would be I Know You’re Out There Somewhere. Whenever we play it live the crowd sings the chorus, and it resonates with people.

How did you feel when you first heard Poor Man’s Moody Blues from Barclay James Harvest?

I thought it was tongue in cheek. But do you know, I can’t even remember what it sounds like now. Sorry, boys!

Do you regard the Moodies as being prog?

Well, we were around before that whole era began. But I get why people put us in that category, and why we appeal to a prog crowd. But I always thought we were more melodic and our style was different to bands like Yes or Genesis. After a while, the prog label slid off us, really. We probably betrayed it. But in a way, our more pop-oriented approach set the template for the way some of these bands streamlined their sound in the 80s.

You and John Lodge have worked so closely together for so long, not just in The Moody Blues but also the Blue Jays. Are you friends?

Well, we’re not the sort of people who spend time together away from the band, if that’s what you mean. But then that’s the case of all of us in the band. People often say that members of a band are like family, but that’s not true for me. I have my brother and sister, and don’t have the same relationship with John. I also think ‘friends’ is the wrong term… there probably isn’t a term that’s been invented yet to describe the way John and I get on. It’s a combination of brotherhood, competition and the way our personalities both clash and also mould together.

In the first few years I was in the Moodies, there was a lot of testosterone flying around. But then the dynamic altered, as some people rose and others sort of retreated. In the 70s, there was an obvious tension in the band that had to be released. In ’74, I was on the sidelines watching what was going on. Thankfully, nothing was said that couldn’t be unsaid. But a few years later this did happen, and Mike Pinder decided he had to leave as a result.

Can you ever see a reunion with Pinder and Ray Thomas?

No. Those guys haven’t played for a long time. You can’t just pull people out of retirement and put them on stage. I was the one who never wanted The Beatles to reform. I loved it as it had been, and knew it could never be the same again. If we did, it would be five really old guys, and all people would end up saying is, “They’re not as good as they were.” That would be the end of the band. Now, there’s a magic and mystery about the five of us, but this would be destroyed by the reality if we ever did get back together.

How much of a shock was it being on This Is Your Life?

I was at a promotional event for a new recording. Then Michael Aspel, the presenter, came onstage with The Big Red Book, and announced, “Hi Justin, this is your life,” and I responded, “Very funny!” I thought it was a joke, and he was actually there to do someone really famous. But it turned out to be me. Then I was locked away for two hours. I was assigned a production girl and a security guy who told me nothing. No matter what questions I asked. In the end, I just said to the girl, “Just tell me, is my wife central to this?” And she replied, “Oh, yeah, yeah.”

Were you at all concerned who might turn up on the programme?

Well, there were some I wanted to be there, and others I really did not want around. But [wife] Ann Marie had been with me throughout my career, so she understood there might have been certain people I have met along the way who it wouldn’t have been appropriate to have there.

I have no clue how she managed to keep it a secret from me for so long. She knew three months earlier, but there were code words between her and the production company to ensure even if I was at home when they phoned I had no idea what was happening. She was captain of the golf club at the time, so for instance if I answered the phone when they called, they’d say it was the club and ask to talk to the captain.

You’re very private, so how did you deal with being on such a major TV show which opened up your life to scrutiny?

Oh, it wasn’t a problem for me. I was lucky that my mother was still alive, so delighted she was there. And I had a lot of friends around, like Kenny Swain the footballer and Marty Wilde, who I worked with just before joining the Moodies. So that was great. And the best thing was, they gave us a magnificent party afterwards.

Do you have hobbies outside music?

Not really. I try to keep fit. I’ve had horses for quite a few years. I always enjoy riding. I did it as a kid, and then got back into doing it in my 20s. But music is my whole life. If I’m off the road even for a few weeks, then I get edgy.

Do you constantly write, even when you’re on tour?

I can only write when inspiration strikes. I also have to have a project I’m working towards, in order to get into the right frame of mind to write songs. I can be very lazy, given the chance.

Have the Moodies written and recorded material which was never released, or have you always put out everything?

Well, when the box set [Timeless Flight] was released in 2013, I thought there were a few songs of which only I have copies. But they managed to find those. They also found things I had completely forgotten about. I listened to them when Timeless Flight came out and you know what? I can’t remember doing those!

In our early days with Decca, the company were very tight on tapes. So, if something was left over from a recording session, it would usually be wiped or recorded over. A lot of things got lost that way.

Do you look back with pride when the band reach a landmark like the 50th anniversary of Days of Future Passed?

I’m not one to celebrate anniversaries. I’ve got so used to seeing such occasions being used as no more than a promotional tool. While I understand the commercial value of these moments, it all gets a bit predictable, and takes away from the genuine pride you might personally have in the event.

What ambitions do you have left to fulfil?

Only to continue doing what we do. To play live and record new music for as long as we can. I’m fully aware that time is running out for me at my age. So many great musicians have gone in the last few years…

You must have seen musicians who were friends die in recent times. Has this made you think about your own mortality?

Not friends, more acquaintances. As for the way it has impacted on me, the only thing I can tell you is that when you get to the age of 71, then you will appreciate what I feel. Until then, no words I use can put people into my mind.

A lot of bands and musicians have done autobiographies. Is that something which appeals to you too?

A Moody Blues book would only be interesting if it was warts ’n’ all. I would be comfortable doing that, because it would make people sit up and take notice. But I can’t see the others agreeing to that. As for a Justin Hayward book… well, I’d rather let my music speak.

People would be amazed that there might be ‘warts ’n’ all’ stories connected to the Moodies. Do you actually have some that might shock everyone?

I’m not gonna tell you, ha! Maybe one day you’ll find out if we ever do this book. We avoided a lot of the controversies which blighted other bands. But we were around in the 1960s, when so much hedonism happened, so you would expect us to have had our moments of indulgence.

Might there be a Moody Blues musical one day?

It has been proposed, and there have been storylines suggested. But they’ve not been right. It’s an easy option, but not necessarily one we’d want to pursue.

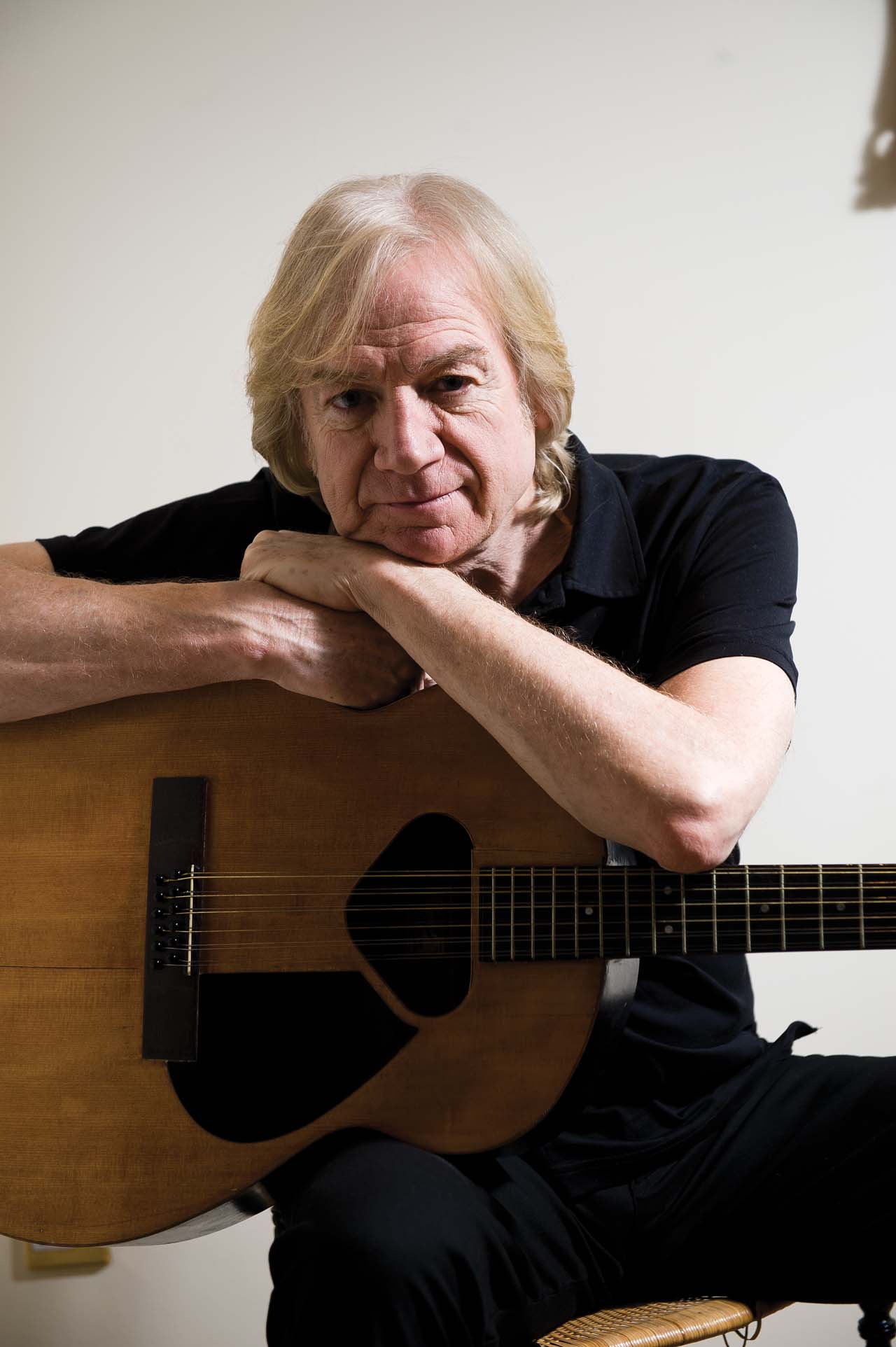

How would you describe yourself as a person?

I don’t know. That’s a question for other people to answer. I never think of my attributes as a person. All I can tell you is that I’m committed to my music, and want to be as good as I can possibly be as a songwriter and musician. I’m always looking for ways to improve. Anything else I might or might not be as a human being I will leave for other to judge.

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.