“She has managed to maintain her position without ever once being sucked into the creative vacuum of celebrity culture”: The less we see of Kate Bush, the more we want to know

In 2011, when Kate Bush released her ninth studio album, Director’s Cut, Prog took the opportunity to explore her career as one of the prime mavericks inside and outside the genre.

The custodians of cultural history will tell you that the summer of 1977 was notable for many reasons: the Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the subsequent banning of Sex Pistols’ God Save The Queen, the undignified death of Elvis Presley, and Donna Summer’s I Feel Love – the first song to be made almost entirely on synthesisers – hitting the top spot. But as the hot summer drew to a close, another new sound was taking shape. A sound quite unlike anything that had gone before, or since.

For six months a new outfit had been popping up in pubs around London. They were a four-piece called The KT Bush Band and were quite at odds with the other groups on a scene that had recently seen a seismic shift away from rudimentary pub rock to the freshly-shorn new wave of louder, more agitated and fashion-conscious punk bands. The KT Bush Band were notable for featuring a relatively delicate looking, dark-haired teenager on vocals – vocals which soared and swooped and sounded like no other.

What curious punters didn’t realise was that these odd songs were entirely penned by the singer and were just a selection of the 200 she had already written and demoed, and in fact she had already long since been signed by EMI.

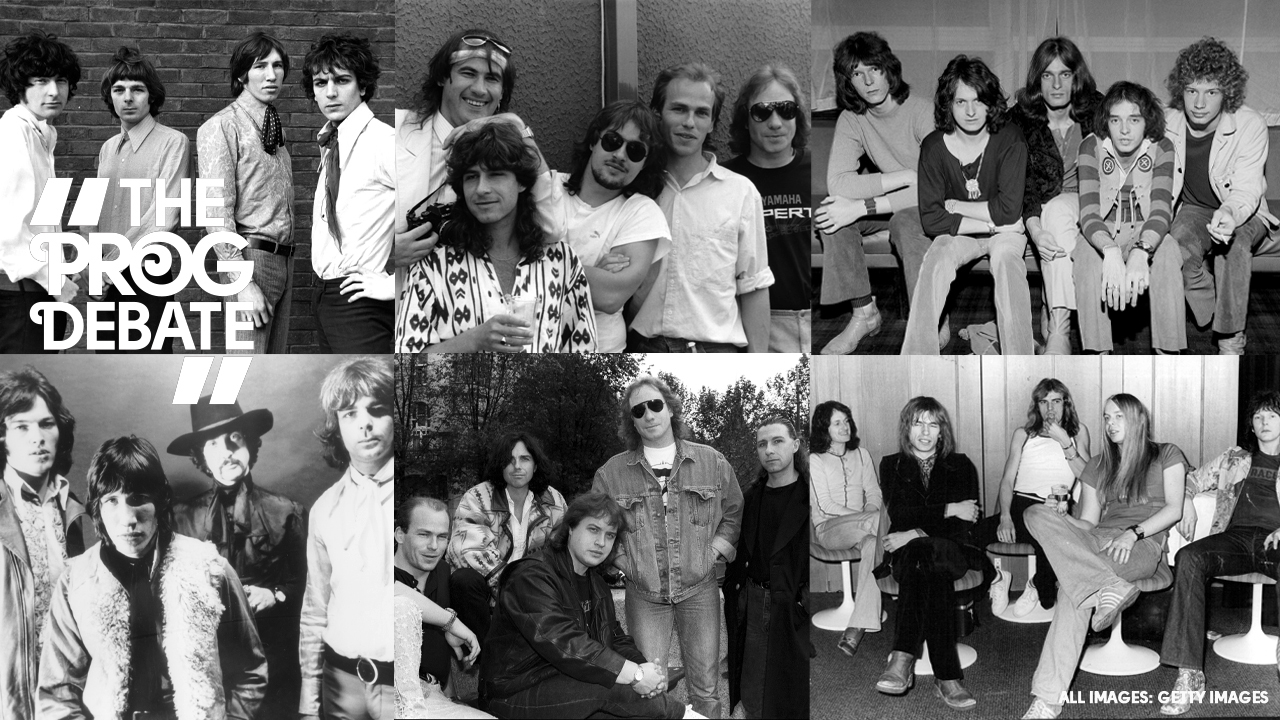

That hot August, Kate Bush entered a studio to work on her debut album. She was backed by some prog heavyweights including David Paton (Pilot, Alan Parsons Project, Camel), Ian Bairnson (Alan Parsons Project), producer/arranger Andrew Powell (Henry Cow, Cockney Rebel) and executive producer David Gilmour of Pink Floyd.

Kate Bush was new. Brand new. But in her collaborators there was a weight of British musical history, and in her music a beguiling sense of English mythology. The album was entitled The Kick Inside, and when it was released six months later in February of 1978 – just two weeks after the Sex Pistols’ final show – it would reach No. 3 in the charts, spawn a No. 1 hit and change the face of modern music.

The success of Bush can at least partly be ascribed to Floyd, who had opened major labels’ minds to the commercial potential of experimental music. Gilmour had earned EMI millions, so when he enthusiastically passed on a demo tape that had been given to him by Ricky Hopper, a friend of the Bush family, the boardroom suits paid attention.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The Bush kids were creative. Their mother was a Catholic from southern Ireland, who won medals for dancing and whose family had strong Irish folk roots. Their father was the son of a Methodist lay minister from Essex who had narrowly escaped execution as a conscientious objector during World War I. He’d become a songwriter in his teens; but recognising the instability of such a profession, turned to medicine in order to support his young family.

Born Catherine Bush in Erith, Kent in 1958, Kate had a musical upbringing – there was a lot of classical music in the house and her older brothers John and Paddy were keen folk players (Paddy would become the world’s foremost expert on Madagascan music).

“At six years old Kate was sitting in on our rehearsals, singing along,” says her oldest brother, John Carder Bush. He managed her business affairs, acted as visual director/photographer and, as a keen martial artist, was also her bodyguard. “At about the age of 10 she learned violin – which she didn’t like – but she also wrote poetry, which became songs.

“The songs were very precocious – the subject matter was pretty obscure and they weren’t miserable love songs, which of course are the spine of popular music. Things really started to happen when she was 15, 16, though. She had to think about her A-levels – and though she never actually saw herself as a singer, she considered herself a songwriter. At the same time she saw Lindsay Kemp and became very interested in dance.”

Kemp, who played the shifty landlord MacGregor in The Wicker Man, was an interpretative dancer who had previously schooled David Bowie in mime. Even in her mid-teens Kate’s influences were broad and wide – and distinctly non-pop: classical, world music, piano ballads and avant-garde literature and cinema all filtered into her work.

It was John Carder Bush’s friend Julie Covington – a star of comedy musical drama Rock Follies who had recently scored a hit with Don’t Cry For Me Argentina – who financed Kate’s first demo, the same one which found its way to Gilmour and secured her deal with EMI.

“Artists are just pleased to be offered a deal, however unfair,” says Carder Bush. “Their egos are appeased. But I had trained as a lawyer and our father was a mathematician, so we were able to really understand Kate’s contracts. As a family we were extremely careful and protective from day one. We never used managers. And it all paid off.”

Those literary and dance influences were soon evident in her 1978 debut single Wuthering Heights, which charted the tumultuous love affair of Heathcliff and Cathy Earnshaw from Emily Brontë’s windswept moorland novel.

It nearly all backfired though, when a handful copies of the single were accidentally mailed to radio stations six months before release. “The song was so unique it didn’t fit into any category – and it was either going to work or it wasn’t,” says Carder Bush. “But then they started playing it.”

Fortunately Bush’s otherworldly (and occasionally shrill) delivery and the romantic narrative captured imaginations; Wuthering Heights went to No. 1 for a month – and it was the first self-written chart-topper by a female. The progressive had gatecrashed the nation’s living rooms in style.

At first it does seem absurd – ‘Heathcliff!’ way up there – but it isn’t at all… those shrieks and warbles are beauty beyond belief

John Lydon

“I remember when my mum, God rest her soul, first heard Kate Bush, she said ‘Oh, Johnny, it sounds like bag of cats!’” fan John Lydon told the BBC. “And at first it does seem absurd – ‘Heathcliff!’ way up there – but it isn’t at all; it fits. Those shrieks and warbles are beauty beyond belief to me.”

The whirling, balletic, mime-influenced videos – there were two versions – were as memorable as the song itself, and set a pattern for things to come. Eschewing the tried-and-tested cycle of promotion and touring favoured by rock bands, Bush would increasingly experiment with the emerging form of the music promo. The video for orchestral follow-up single The Man With The Child In His Eyes featured Bush in soft focus in a provocative, flesh-coloured body suit.

While the marketing men and mainstream media were far from subtle in their slavering celebration of Bush’s obvious sexual appeal, she was already proving to be more enigmatic and far smarter than the mindless pop star they clearly hoped to pin her as. When The Man With... won her an Ivor Novello Award and she swiftly followed The Kick Inside with second album Lionheart, the critical acclaim grew.

“EMI really had no idea,” says Carder Bush. “It was run by salesmen who saw her as part of an assembly line – they had obviously never studied her lyrics! So once Kate became a success, they barged in with sexy photo shoots, offers of Las Vegas residencies and Bond themes. She said ‘no’ to all of them because it was the brain and not the body that was Kate’s real quality.”

Kate has never dealt with bullshit; and promotion is 99 per cent bullshit. She hated it. So after that it didn’t matter what the record company said

John Carder Bush

Rush-released in November 1978, Lionheart was accompanied by a rigorous six-week tour whose heavily choreographed shows involved multiple set and costume changes, along with an onstage magician. They represented the most ambitious live extravaganzas since Bowie’s, earlier in the decade.

“The tour was utterly exhausting and utterly successful,” says Carder Bush. “That success changed all of us – we were wary and we kept everything close. Kate has never dealt with bullshit; and promotion is 99 per cent bullshit. She hated it. So after that it didn’t matter what the record company said – she paid no attention to them.”

Spent, Kate vowed never to tour again. Instead she and her family took control of all her affairs, and relations with the media were similarly pared back. And so a dichotomy emerged: at the age of 21, Kate Bush was a bona fide pop star about to embark upon a hugely successful creative run of albums; yet one who would become less publicly visible the more famous she became.

As she retreated to the studio, rumours would abound about her and she would do little to dispel them – like the (apocryphal) anecdote about the time EMI executives arrived at her house to ask what she had been working on, to which she produced some cakes from the oven.

Ultimately though, Bush’s reclusive tendencies would be the making of her. As chart music went through a period dominated by glossy pop that was all veneer and little content, Kate Bush’s outsider status worked to her advantage.

A string of albums throughout the 80s went to Nos. 1, 3 and 1 respectively – Never For Ever (1980), The Dreaming (1982) and Hounds Of Love (1985).

No one song was easy to pin down, with Bush’s music drawing on murder ballads, the childhood wonder of nursery rhymes, her part-Celtic genealogy, the mythology of a lost Albion favoured by some prog and pastoral folk singers, the ethereal end of goth, the organic tones of early music, digital synth pop and emerging sequencing technologies.

Hounds Of Love alone spawned yhree classic singles – Running Up That Hill, Cloudbusting and the tumultuous, dramatically-heightened title track – and further reiterated her prog tendencies by devoting the entire second side of the album to a an experimental opera, The Ninth Wave, whose name came from a Tennyson poem. She also helped define the 1980s whilst being unlike anything else in that era: her skill was not to experiment in the live arena but by embracing emerging technologies in the studio .

“For three or four years it was a rollercoaster for Kate,” says Carder Bush. “She was being sent all over the world, and fortunately she had stockpiled a lot of songs. But when that stockpile ran out she was expected to come up with an album, then promote it, go on TV, all within a year. Well, the type of artist Kate is meant that just couldn’t work. That’s why each album has taken longer and longer to come to maturity.”

It mattered little: fans agree that anything Kate Bush does is always of interest. In an age of over-exposure, her relative seclusion offers a continued sense of intrigue and mystery.

Twelve years of Garbo-like silence fell between between 1993’s The Red Shoes and 2005’s Aerial – but then good art is worth waiting for. Bush has managed to maintain her position for over three decades without ever once being sucked into the creative vacuum of celebrity culture. The less we see of Kate Bush, the more we want to know.

Writer and academic Deborah M Withers recently published an analysis of Bush entitled Adventures In Kate Bush And Theory that considered “the polymorphously perverse Kate, the witchy Kate, the queer Kate; the Kate who moves beyond the mime” and in essence suggested that Kate Bush is many things to many people.

She supplies me with all the clues and it’s up to me to put the answer together – well, that’s like the Quran of music

John Lydon

“She supplies me with all the clues and it’s up to me to put the answer together – well, that’s like the Quran of music,” says John Lydon. “Surely that’s what we’re all looking for? No easy answers to anything. It’s not about rolling in the money, it’s about the joy of knowing that what you’ve done really touches people’s hearts.”

There’s not enough room to list those who Bush has influenced – but she can certainly be heard in prog singers such as The Reasoning’s Rachel Cohen and Mostly Autumn’s sometime triumvirate of Anne-Marie Helder (who says “Kate’s legacy is one of total creative freedom, taking risks and keeping her integrity”), Olivia Sparnenn and Heather Findlay and beyond the genre to Bjork, Tori Amos, PJ Harvey, Bat For Lashes and thousands of others.

Then there are the bands: Coldplay, Suede and Muse cite her as a key influence; hip-hop artists want to collaborate; while Alan Partridge continues to harbour a long-term obsession and The Mighty Boosh’s Noel Fielding likes to dance like her on the telly.

Bush’s latest album, Director’s Cut, is suitably contrary too, in that it is wholly comprised of reworkings of previously released material (from The Sensual World and The Red Shoes). What’s more, one song utilises text by modernist writer James Joyce while another features computerised vocals by her 13-year-old son, Albert.

Today Bush may not be so obviously viewed as a practitioner of prog rock – not at first glance anyway. Yet her career history and collaborations are inextricably tied in with prog and her ever-evolving output has much more common with the genre than the pop world in which she first found herself operating.

In fact, Kate Bush is prog’s first pop star and pop’s first prog star. And one who is always capable of delivering nothing less than the unexpected.