Rock stars seem to be passing away with appalling regularity these days. This year’s abnormally high fatality rate has already claimed David Bowie, Glenn Frey, Paul Kantner, Dale Griffin and Jimmy Bain, among others, struck down by physical illnesses that refused to quit.

The manner of Keith Emerson’s recent demise, however, seems particularly tragic. On March 10, the 71-year-old died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound at his home in Santa Monica. After officially logging Emerson’s case as a suicide, the Los Angeles County coroner’s report listed further significant causes of death as heart disease and depression, caused by chronic alcohol use.

The overwhelming public reaction to his death was one of shock. But for those closer to him, there had been, for some time, signs that all had not quite been as it should in Keith Emerson’s life. His girlfriend, Mari Kawaguchi, revealed to The Daily Mail that a forthcoming gig in Japan had left the keyboardist “tormented with worry” after long‑standing nerve problems in his right hand and arm appeared to be getting worse. Despite undergoing an operation some years ago, she said, Emerson was still in pain and concerned that his musical capabilities were being steadily eroded. “He was planning to retire after Japan,” Kawaguchi is quoted as saying. “He was a perfectionist and the thought that he wouldn’t play perfectly made him depressed, nervous and anxious.”

Author and film producer Jill Gambaro added fuel to this theory when she gave an interview to the LA Weekly just after Emerson’s death. In it, she disclosed that she and Emerson had been in contact two years earlier, when Gambaro was researching her book, The Truth About Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Their email exchange included Emerson discussing the debilitating nature of focal dystonia, a neurological condition that often affects a group of muscles in the hand and wrist. As a long-term sufferer of repetitive strain injury herself, Gambaro began to discover that it was a serious issue for many musicians of a certain age. “Musicians can’t talk about their injuries because then they won’t get hired anymore,” Emerson wrote. “So there’s a lot of people basically suffering in silence.”

The LA Weekly picked up on one Emerson quote that seemed almost too prophetic: “Nobody wants to employ a session musician with any disability. Some musicians have resorted to suicide.”

It wold be easy to view Emerson’s death as a final, desperate response to this deteriorating condition, but that would be grossly over-simplistic. Rather, as is often the case with such terrible tragedies, it appears more complex than that. “I’m sorry to say it was not wholly shocking to any of us who knew Keith closely,” laments Greg Lake, his former bandmate in Emerson, Lake & Palmer. “It was likely to happen. My recollection is that his depression went back as far as 1977, when we were making [ELP’s] Works Volume 1. I’m not a doctor, but in retrospect there were indications that all was not well. I think Keith was a troubled soul, or at least one side of him was. He was really happy when he was playing, but when he wasn’t playing, he went into a dark place. And that was the problem, really.”

“I believe it was a combination of factors,” Lake continues. “He’d known about his hand since we made In The Hot Seat [1994], so that didn’t come as any shock to him. In any case, Keith was 71 when he died and where did he think he was going? You’d be retiring from active playing at that age, wouldn’t you? So I don’t think that was wholly the story. I think he got very depressed and compensated for that in some ways. And maybe the whole thing just crashed. I think that’s probably nearer the truth.”

Carl Palmer, who is currently organising a tribute concert for Emerson in the US, can relate to at least one of his ex-colleague’s problems. “I had both of my hands operated on for carpal tunnel in 1997,” he states. “And Keith had his right hand done either just before or after me. But by the time ELP got back together to play the High Voltage Festival in 2010, the operation had worn out and it was causing him great difficulty.

“I was the one who had to end ELP after that, because it had taken five weeks to rehearse for that one show in Victoria Park. It was a lot of strain for Keith and I couldn’t see him going through more of that. We ended up putting a lot of stuff onto sequencers, as Keith couldn’t really perform for more than half an hour at the level he was used to. Because even to this day, he’s the greatest musician I’ve ever played with. That’s really important to me and it wasn’t something I could keep on putting him through. He was relieved when I ended the group. And right up until the end of Keith’s life, his hand was obviously playing havoc with him.”

Palmer prefers to view Emerson’s death as “a bit of a mistake. I don’t think he wanted to take the easy way out because he could still compose. Only in the middle of last year he was out there doing it [with Norwegian classical conductor Terje Mikkelsen at the Barbican in London]. So he had a lot of stuff going on and I think his death came about because some other things just got in the way, along with the problems that he had.”

It’s also instructive to note a professional’s diagnosis of the situation. UK psychologist John Callard, who has spent over 40 years studying cognitive behaviour and mental illness, suggests that loss of control over his playing ability may have been a crucial factor in Emerson’s decision to take his own life. “When the thing that makes us who we are is no longer there, it’s a massive challenge to readjust,” he explains. “Emerson chose not to have a future without what was his core activity. So in that respect he chose to regain control by taking his life. He had his notion of self ripped apart and probably knew there was nothing he could do to bring it back to how it once was. So seeking support or psychological therapy was not an option. The mental capacity to create remained, but the physical capability was diminished. And he appears to have been unable to accept this deterioration and wasn’t prepared to compromise. Keith Emerson made a choice and, however hard it may be, we have to accept that.”

While no one can claim to know exactly what was going on in Keith Emerson’s head in the days and hours prior to his death, Callard’s comments, along with those of Lake and Palmer, seem to suggest it was his very musicianship that was his undoing. Or, to be more precise, the extraordinary standards he set himself. Emerson wasn’t just a great keyboard player – he was the leading light of his generation.

Born in West Yorkshire on November 2, 1944, his presence on the British rock scene, first with The Nice in 1967 and then on to ELP throughout a dizzyingly successful 70s, coincided with a golden era of home-grown talent. But none of them could quite match Emerson’s adept balance of showmanship and technical expertise.

“He was the pioneer, the godfather of rock keyboard-playing,” asserts Geoff Downes, the man behind the keys for Asia and, briefly in the early 80s, Yes. “People like Jon Lord and Rick Wakeman were big influences on me, but Keith really started it all. I don’t think there’d been anyone like him before. I saw The Nice at the Isle of Wight Festival in ’69 and Keith was so inspiring. The guitarist was usually the guy who got all the glory, but all of a sudden Keith was the focal point. It was just incredible to see what the keyboard was capable of. This guy was the full nine yards; he had everything going for him. And I think The Nice was pretty much a trial run for ELP from Keith’s standpoint.”

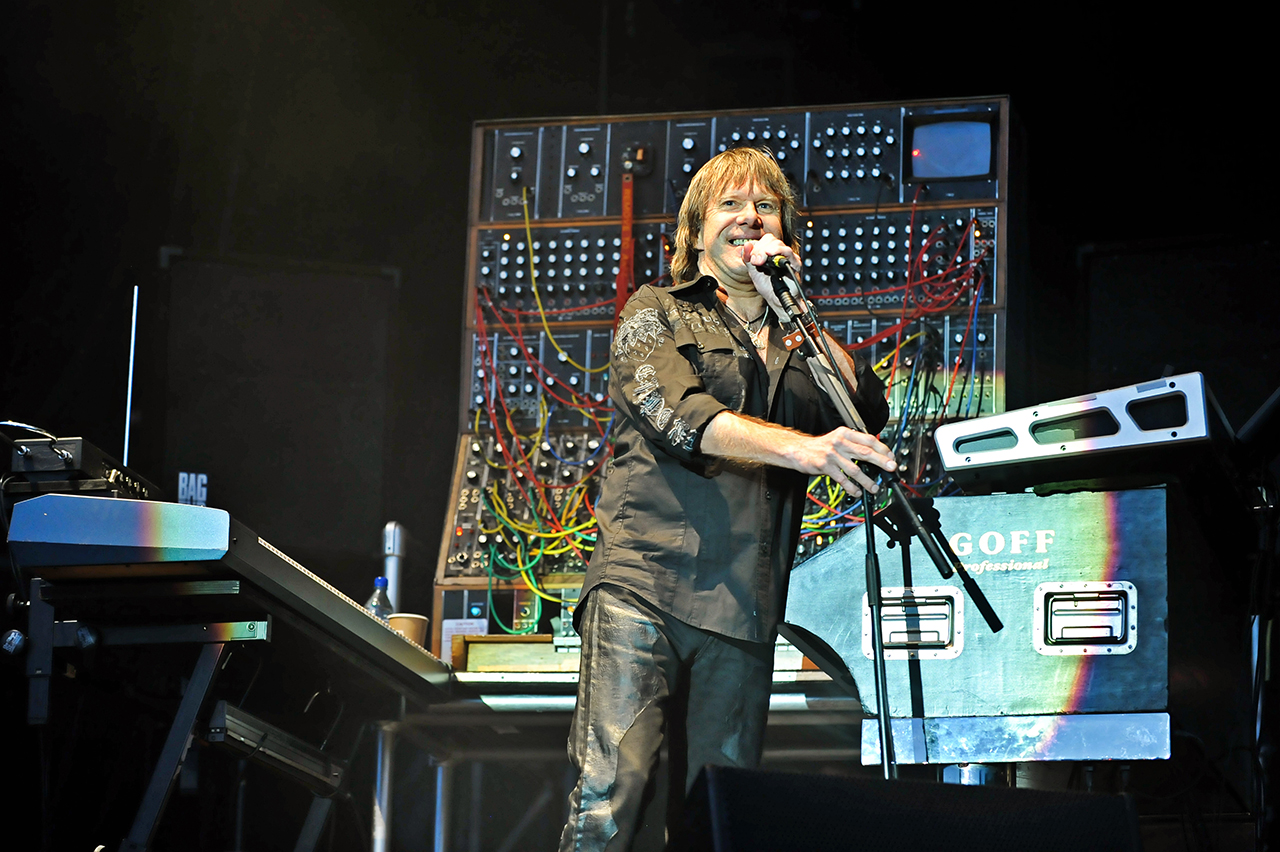

Emerson found a perfect outlet for the full range of his abilities in ELP. A dazzling virtuoso who sought to blend the realms of rock and classical music, his flamboyant stage demeanour – spinning pianos, fireworks, hydraulic rigs, silver bat wings, daggers that held down certain keys before being ceremoniously thrown into speaker stacks – chimed with the age of proggy theatre. Grand statements require grand designs. And Emerson became synonymous with the Moog modular synthesiser, pioneering its use on tour and continuing to work closely with its manufacturers.

“Keith knew that no matter how well he played, there was a certain amount of stage presentation that he had to do,” recalls Palmer. “He always wanted more, that’s what drove him. So I was ready to have a spinning drum riser and gongs and the rest of it. And Greg was ready to have the biggest Persian carpet in the world. During the 70s we created some of the greatest music ever made and Keith was a pioneer of the amazing British art form called progressive rock. He laid down the blueprint, especially on concept albums like Tarkus, which was just mind-blowing. ELP really was three individuals and none of us sat on the fence. We never argued over money or women – the only thing ELP ever argued over was music.”

Greg Lake, meanwhile, maintains that Emerson “put keyboards onto the world stage in terms of being a lead instrument. For me, the essence of Keith Emerson was the Hammond organ and, after that, his innovation with synthesisers. On things like Fanfare For The Common Man or Welcome Back My Friends, he made the synths work in a very colourful and inventive way.”

After ELP disbanded in 1979, Emerson threw himself into solo projects, soundtrack work and various collaborations over the decades. There were a couple of ELP reunions, though by then he had started to develop repetitive stress disorder.

Another musician friend who has been struck with something similar is bassist-singer John Wetton, formerly of King Crimson and, most recently, Asia. “I have carpal tunnel and I’ve had two operations, neither of which have made any difference at all,” says Wetton. “It’s depressing, but at least I can still sing. But if all you’ve ever done is play piano, like Keith did, it must be hellish to find out you can no longer perform to the best of your ability. By the same token, I would hope it’s not terrible enough to make me think about topping myself. That’s the tragic bit. I’d like to have thought that if Keith had picked up the phone to me I could’ve talked him out of it, because he still had so much to live for. His musicianship was only one tiny fragment of his personality.”

Wetton, who is currently undergoing treatment for cancer, highlights another aspect of Emerson’s nature: “He was a lovely man and, as I found out later, very caring. When I got sick last year, he was the first person on the phone. That’s what makes his death such a conundrum, because somebody who cares that much about other people is usually the last one to reach out themselves.”

Talk to Keith Emerson’s friends, peers and old bandmates and the same portrait starts to emerge: a sweet, compassionate, down-to-earth man. And, of course, one hell of a musician. “There’s no question that music was the central, pivotal purpose in Keith’s life,” Greg Lake affirms. “And that’s what I hope he’s remembered for, not for any rock star indulgence. It’s the music that gave so many people so much pleasure.”