An elegy for an officer and a gentleman…

We have a habit of seeing our musical heroes as invincible and immortal but of course, as Keith Emerson himself noted in 1968, “Art is long, life is short.” A member of that Olympian generation of musicians blessed with prodigious amounts of ability and ambition, Emerson was a visionary and an innovator, keen to forge a sound that possessed both the grit of rock and the grandeur of the classical composers that both inspired and fuelled him.

Having served his time as a journeyman pianist and jobbing organist, it wasn’t until he was with The Nice that he took full advantage of the 1960’s penchant for breaking boundaries. A showman through and through, Emerson intuitively grasped the fact that sometimes being technically proficient or good at what you do isn’t always going to take you to the next level. The Nice’s 1968 fusion of Leonard Bernstein’s America may well have been a commentary on that country’s foreign policy in Viet Nam but it’s not until Emerson starts burning the US flag that the heads really start to turn.

Gouging daggers into the keys of his Hammond L100 looked wonderful. Hauling the much-abused keyboard about the stage with a ritual savagery had a mesmeric, jaw-dropping power. In reality, those daggers would have less and less to do with the eerie wailing and apocalyptic explosions emanating from the stricken instrument - that would mostly be the Hammond’s reverb plate and motor drive. But it was a classic piece of party-trick misdirection that made Emerson’s on-stage persona nothing less than magical.

Emerson’s meld of rock and classical forms in Ars Longa Vita Brevis (1968) or Five Bridges (1970) were acts of pioneering, almost reckless, heroism. As an aside, only recently, I was in touch with Emerson to ask if he’d be interested in updating the Five Bridges suite to reflect the seven bridges which now cross the river Tyne, which indeed, in principal, which he was.

With The Nice but especially with ELP, Emerson provided the gateway for so many of his millions of fans to discover and explore for themselves, the source material he adapted from classical music. The chances are that if your album collection also contains the works of Bartok, Rachmaninov, Mussorgsky, Copland Ginastera and several others,it’s probably thanks to Keith Emerson.

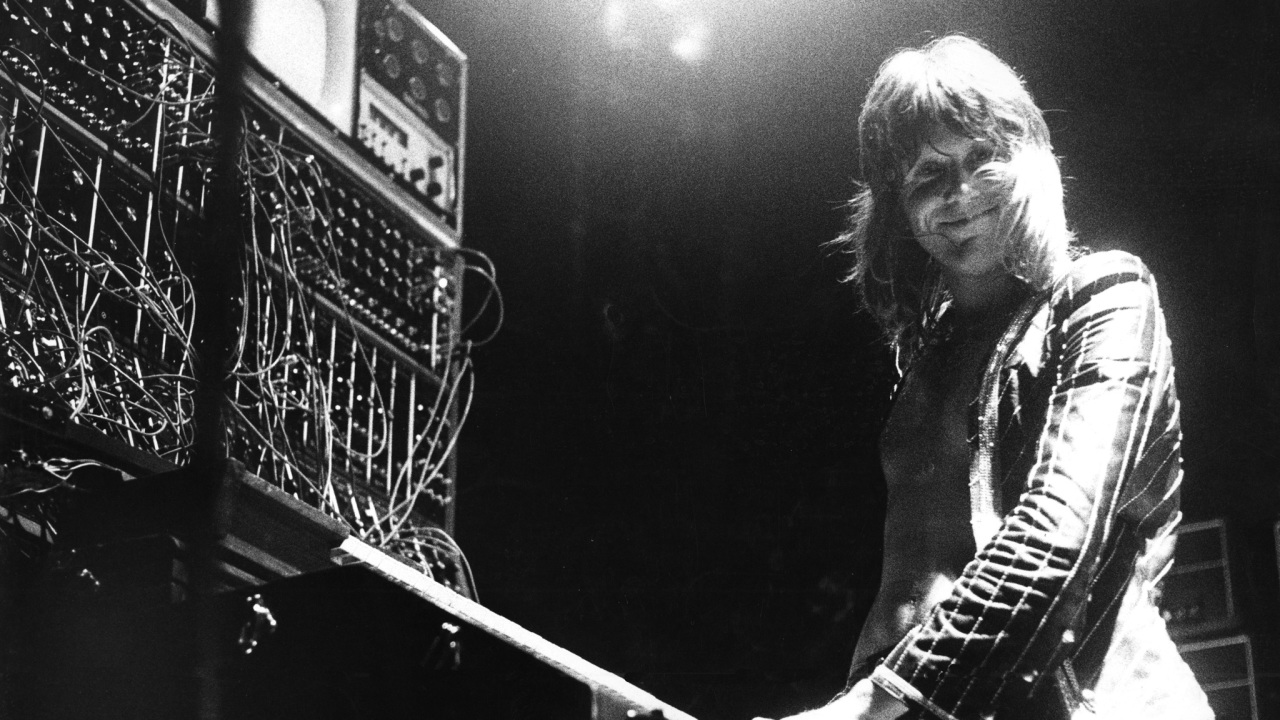

His relationship with Bob Moog and the integration of the synthesiser into the everyday vocabulary of rock music shouldn’t be overlooked or underestimated. That huge modular system, with its banks of oscillators, serried dots of HAL 9000-like red light eyes remorselessly blinking, and tangled knots of patch-leads made it look like Emerson was a lightning rod for the wild, electrifying spirit of modernity. He plugged into the sounds of the future and pulled us along with him.

Today we are inured to the instrument such is its ubiquity. But when Emerson started surfing the sine-wave in 1969 it was still a relatively rare and vividly exotic colour in the artist’s palette. Emerson’s enthusiasm and understanding of how it might be used beyond a few novelty sci-fi-sounding bleeps and burbles was instant and way in advance of most of his contemporaries.

The famously off-the-cuff Moog solo at the end of Lucky Man is a perfect example of how Emerson transforms an acoustic ballad into a strange, altered reality. Daringly at odds with the song’s folkloric pastoralism, he pulls both song and listener into some indeterminate future space. The reason we love that solo so much isn’t because of it’s dexterity or typical flamboyance; it’s because we get a sense of Emerson’s child-like wonder at the noises emanating from what was, at the time, an extremely temperamental box of tricks.

The recent surround sound mix of ELP’s Trilogy (1972) shines a light on all the labour-intensive overdubbing that went into transforming the monophonic lines comprising Abaddon’s Bolero into the resplendent ground-shaking harmonies that triumphantly close the album. Perhaps more than anyone else in rock music, Emerson raised the bar, setting off a space race of sorts for the then still-infant synth industry to see who could come up with the first reliable polyphonic instrument.

As a member of ELP, Emerson was no stranger to the rock’ n’ roll circus of excess. His panache and flashy persona would have him take most of the flak when ELP became a byword for indulgence. Yet in recent years,the wheel had turned and with it something of a critical rehabilitation of his ground-breaking work with The Nice and ELP. The driving, nascent jazz-rock of For Example, the bold, jagged experimentalism of Tarkus, the yearning spirit caught in The Endless Enigma, or the Copland-esque sunny uplands of his Piano Concerto No.1, all show an artist with a truly impressive facility to take a melody and transform it into something very special indeed. Those pieces, and so many more besides, will stand the test of time with the lives they touched. “Art is long, life is short,” rings as true now as it did back then. Through all the music music that flowed from him, Keith Emerson will stay with us, enabling those who loved him to hang on to a dream for a long time to come.