In The Year Of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion’s meditative exploration of sudden death and loss, she notes, “Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant.” Keith Emerson’s death in March this year came as a sudden blow to countless numbers of fans around the globe. Following so soon after the news of George Martin’s passing in the same week, the announcement was met with wearied dismay that yet another two hugely influential figures had been added to a grim roll call, which, in the last 12 months, included Edgar Froese, Ornette Coleman, Chris Squire, Lemmy and David Bowie.

Though artistically diverse, the common thread linking them all is that they hailed from a generation for whom excellence, innovation and experimentation was second nature. Whereas most mentioned succumbed to natural causes or illnesses, what made Emerson’s passing all the more shocking was the means of his going. Found in their apartment in Santa Monica, Los Angeles, by his long-term partner Mari Kawaguchi, Emerson had taken his own life with a single gunshot to the head.

We know that Keith had experienced problems with his right hand for many years. He required corrective surgery during the making of 1994’s In The Hot Seat, and was only able to complete the album by overdubbing with his left hand. When ELP re-formed for what would be their final gig at London’s High Voltage Festival in 2010, sequencers did all the heavy lifting when it came to those famously dextrous and exacting rhythmic lines which, in part, defined his playing.

The fact of the matter is the greatness of Keith Emerson was when he was himself, not when he was trying to get acceptance in the classical world.

We know also that he was dogged by depression in recent years, and that plans for a Japanese tour in 2016 had led him to worry about whether his deteriorating right hand would be able to cope with the demanding repertoire.

It’s simply not possible to say whether any of this contributed to Keith Emerson’s death. It’s impossible to truly know or understand what had led him to this moment; the point at which no other solution made sense to him any more. All we can say with any certainty is that in that dark, dreadful moment, everything was lost. Life, as Joan Didion observed, changing in the instant.

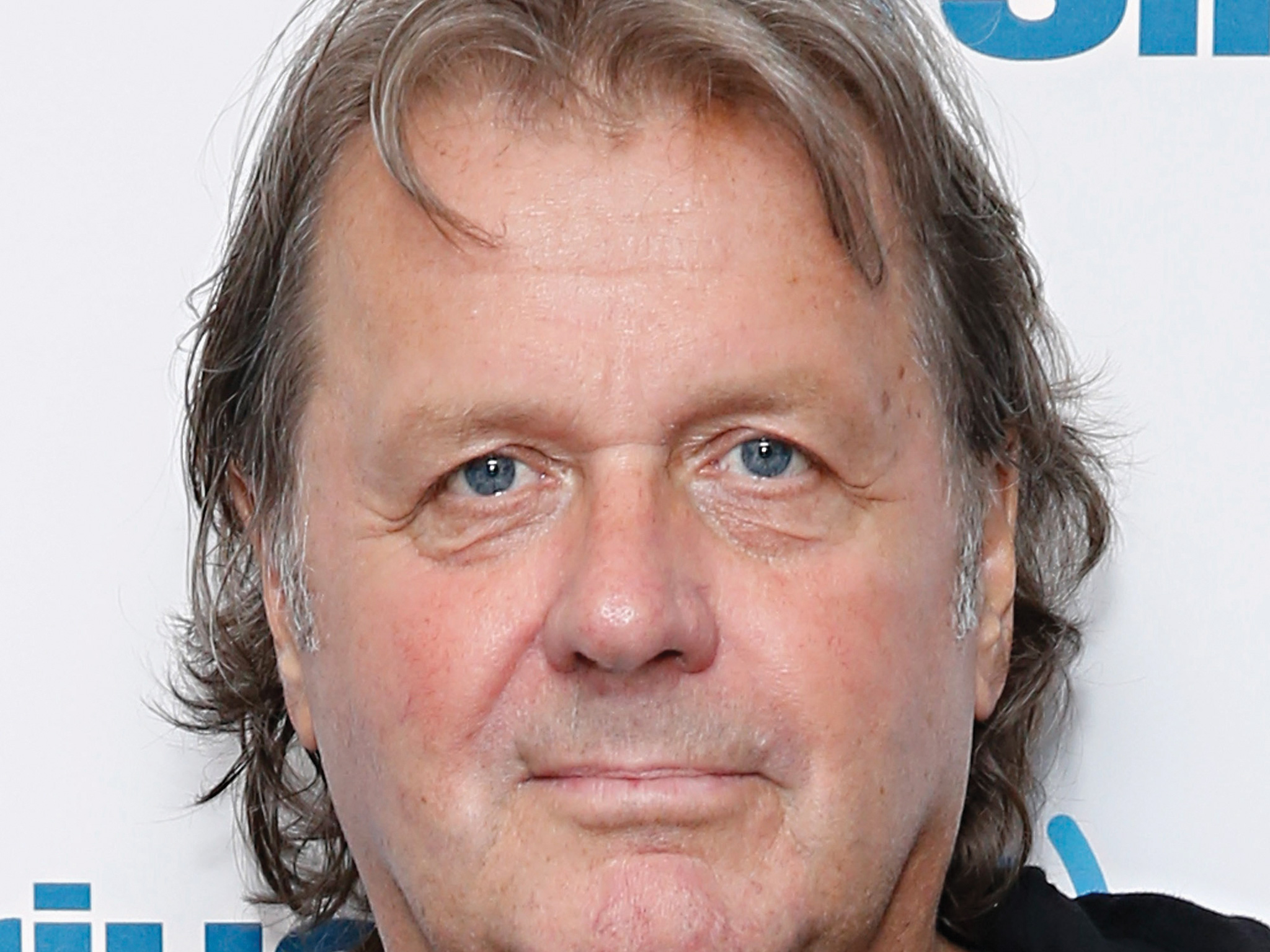

“It was following morning as I got onto the bus when I got the call,” says Carl Palmer, who was gigging in Italy with his band at the time. “It wasn’t something I thought was going to happen. None of us thought it would. We knew that there were problems but didn’t realise the extent of them. I don’t think many people did, even the people closest to him. From that point of view, it came out of the blue.”

Palmer reveals he had spoken to Emerson last year about the pair playing together at a special performance in 2016. “Because it’s my 50th anniversary as a professional musician, I said to Keith, ‘Let’s pick one date on my American tour that would suit you, and let’s play Carmina Burana, Fanfare…, Peter Gunn or whatever you’d like to play.’ He said yes, and we had it set up to do the gig but just hadn’t decided on the date. So that was very sad.”

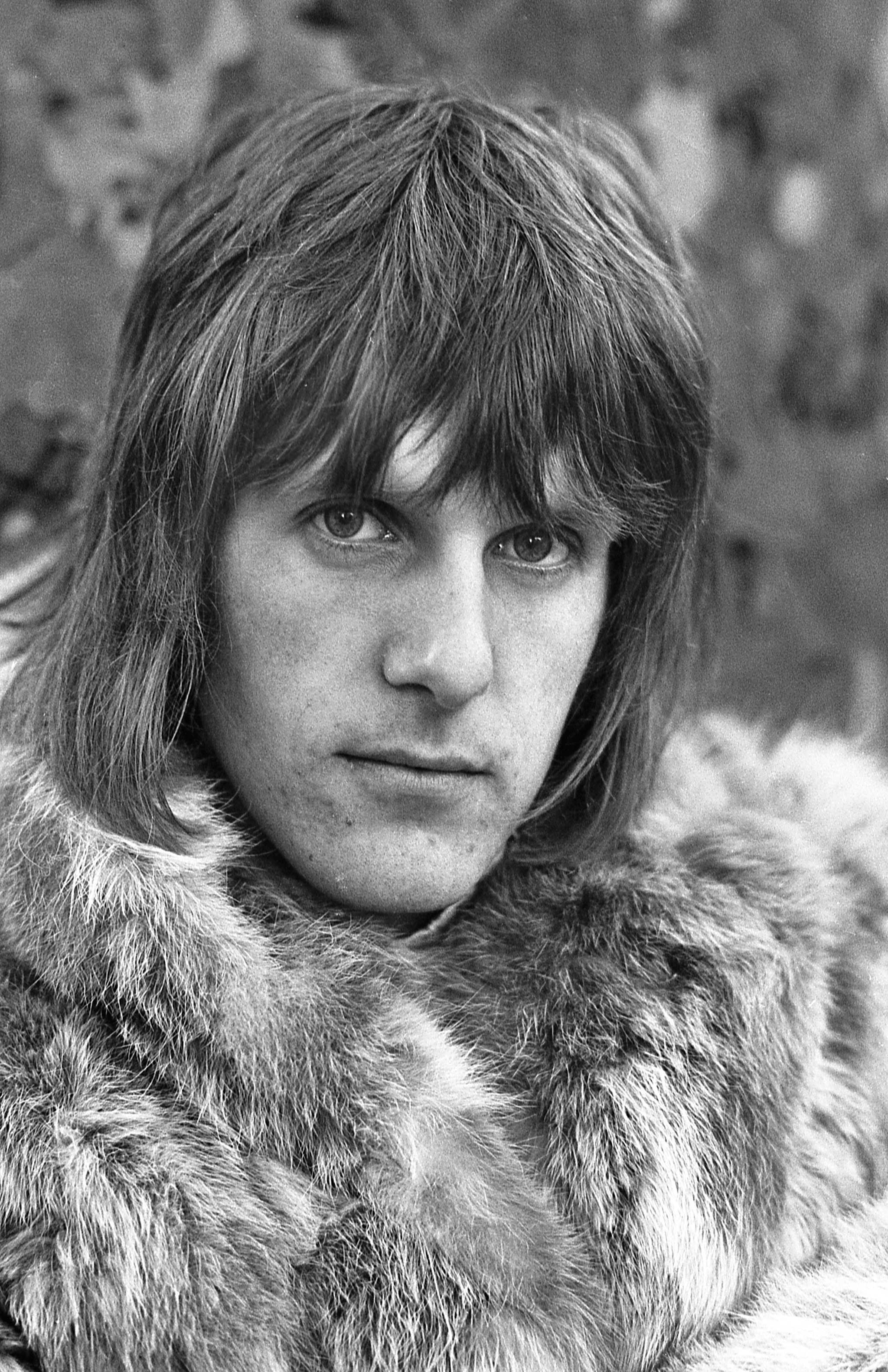

Lee Jackson, bassist and vocalist with The Nice, remembers Emerson primarily as a friend but also as a unique musical force. “There was nobody doing what Keith did,” he says firmly. Too often dismissed simply as a career footnote, there’s a wild, untamed vitality to The Nice in their later period, featuring Jackson and drummer Brian Davison.

It was here Emerson honed his skills not only as showman but as an instrumentalist. Jackson recalls when he and Emerson were members of Gary Farr And the T-Bones in 1965, and shared an ambition to go beyond the soul-tinged pop filler of the day. “Keith and I said that one day, if we got the chance, we’d form our own band to play intelligent music. We’d sell it by dressing up like a pop group; whatever the fashion was at the time, that’s what we’d do. We’d try and do clever stuff but we’d make a show out of it as well.”

The Nice’s persuasive mix of spiky psychedelic pop and Emerson’s novel appropriations of themes by JS Bach and jazz pianist Dave Brubeck in Rondo from their 1967 debut, The Thoughts Of Emerlist Davjack, did just that.

Following guitarist Davy O’List’s departure, 1968’s Ars Longa Vita Brevis and 1969’s superb, but criminally underrated and jazz-infused Nice contained hard-edged, original material as well as vibrant, rocking arrangements of classical themes. Across those albums and others released after The Nice broke up, it’s possible to discern the extent and implications of Emerson’s progressive aspirations and his determination to push forward.

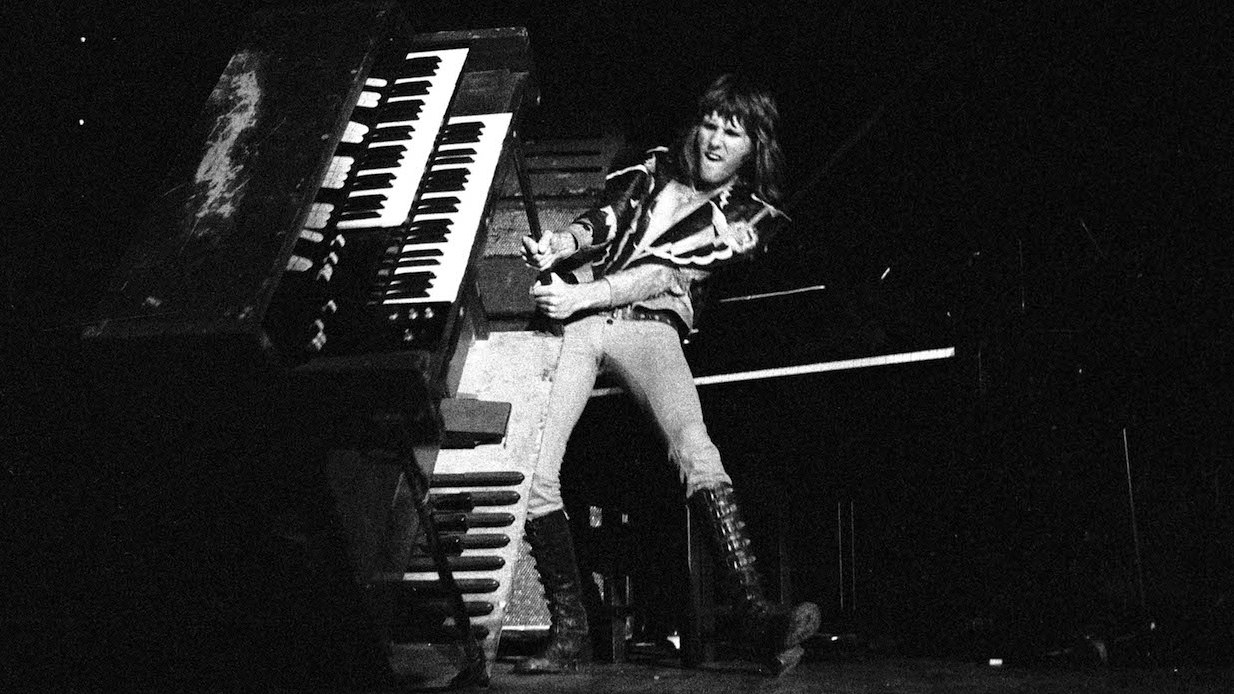

Very much a part of the radical tide of experimentation sweeping through all parts of the 1960s arts scene, Emerson’s precocious musicality ensured there was plenty of substance behind the ‘wild man of rock’ image for which he was also gaining a reputation. Seeing through the artistic apartheid segregating Bach from Brubeck or Dylan from Dvorak, when The Nice augmented their sound with an orchestra it wasn’t a gimmick but the actions of a man on a mission. As he made clear in the earnest notes accompanying The Nice’s Five Bridges, he was “trying to build bridges between those musical shores which seem determined to remain apart from that which is a whole”.

By the time Five Bridges reached No.2 in the charts in June 1970, The Nice were no more. However, the piece evidenced Emerson’s long-held desire to merge rock group and orchestra, and would have significant repercussions for the future.

Lee Jackson admits Emerson’s abrupt abandonment of The Nice hit hard. “The Nice did end badly and I didn’t speak to Keith for about six months,” he recalls. “We were all hurt by it. A few months later though, he rang, very excitedly, to tell me his then-wife, Elinor, had had a baby and I thought then that he wanted to be friends again. So I went round there and we resumed our friendship which lasted over 50 years until the day he died. He was a lovely person… I loved the guy.”

For Jackson, Emerson’s position as one of the true musical pioneers of his generation is unassailable. “Not that Keith would ever have laid claim to it but I would say he invented progressive rock. He didn’t intend to, he didn’t know he’d done it, but that’s what it was. That’s what he did.”

With ELP, Emerson’s writing matured and refined, leading to some of his most complex, challenging work, but which would nevertheless sell in the millions. Add to this his early adoption and integration of the synthesiser, no other rock keyboard player looked or sounded like Keith Emerson. He was, quite simply, the gold standard against which the other keyboard-dominated bands of the day would be measured, and, after topping readers’ polls in the music press proved year after year, found wanting.

At the height of their powers, ELP were in competition with nobody but themselves. “That’s exactly what it

was all about,” agrees Palmer. “That internal competition within a band, if you can keep that going, that’s what drives it. When you get into a writing mode, normally those people will not sit on the fence. They’ll say they like it or they don’t. You’re always going for the best. ELP never argued about money, over any women, or any affairs like that. The only thing we’d argue over would be music. We could argue over four bars for about four years!”

Greg Lake remembers those moments too. “One of the things they’re quite introverted and then the other way, as Keith would often say himself, ‘I’m an exhibitionist.’ So there was that about him as well. It’s rather like comedians. When they’re onstage they’re as funny as hell… But in away, I suppose, it’s some sort of balancing factor. Keith was most definitely multifaceted from a personality standpoint.”

Palmer agrees: “I think if you were to go back and look at the actual make-up of the band, and the way people were situated within that environment, history tells us there was a problem as far as confidence.

“ELP didn’t play England for about three years,” he adds, “and that’s because somebody said they didn’t think the band were very good. 400,000 people said the band was fantastic, but that one person who said it wasn’t very good affected Keith and he didn’t want to play the UK any more, and we didn’t play here for three years. He was always incredibly fragile.”

Emerson’s desire to be accepted as a composer of contemporary classical music was a long-harboured dream and his Piano Concerto No.1 from 1977’s Works Volume 1 represented the culmination of a voyage properly begun with Five Bridges. Not everyone in the band saw it that way. The vision of a touring orchestra was bold but hubristic, saddling the band with enormous debts and came to define ELP’s reputation for vulgarity and excess in an increasingly hostile and sceptical press.

“I think it all started going wrong with Works Volume 1,” says Greg Lake. “That to me is when the band started to go in different directions, and although we were trying to co-operate, everybody was off doing their own thing. It was clear to me the band was really disintegrating and, eventually, I think that became clear to the fans. All of a sudden it was all about orchestras, but people didn’t want to go and see an orchestra. They wanted to see ELP.

“The fact of the matter is the greatness of Keith Emerson was when he was himself, not when he was trying to get acceptance in the classical world. The greatness of Keith Emerson for me was when you listened to Tarkus

or Trilogy or Brain Salad Surgery. When he was playing innovative rock music, whether it was beautiful or powerful, that was him at his best.

“If I could have 10 minutes of Keith Emerson playing now, it would be him on the Hammond organ,” says Lake. “And if I got bored with that, I’d have him playing the synth. Those were the instruments he could make talk and walk.”

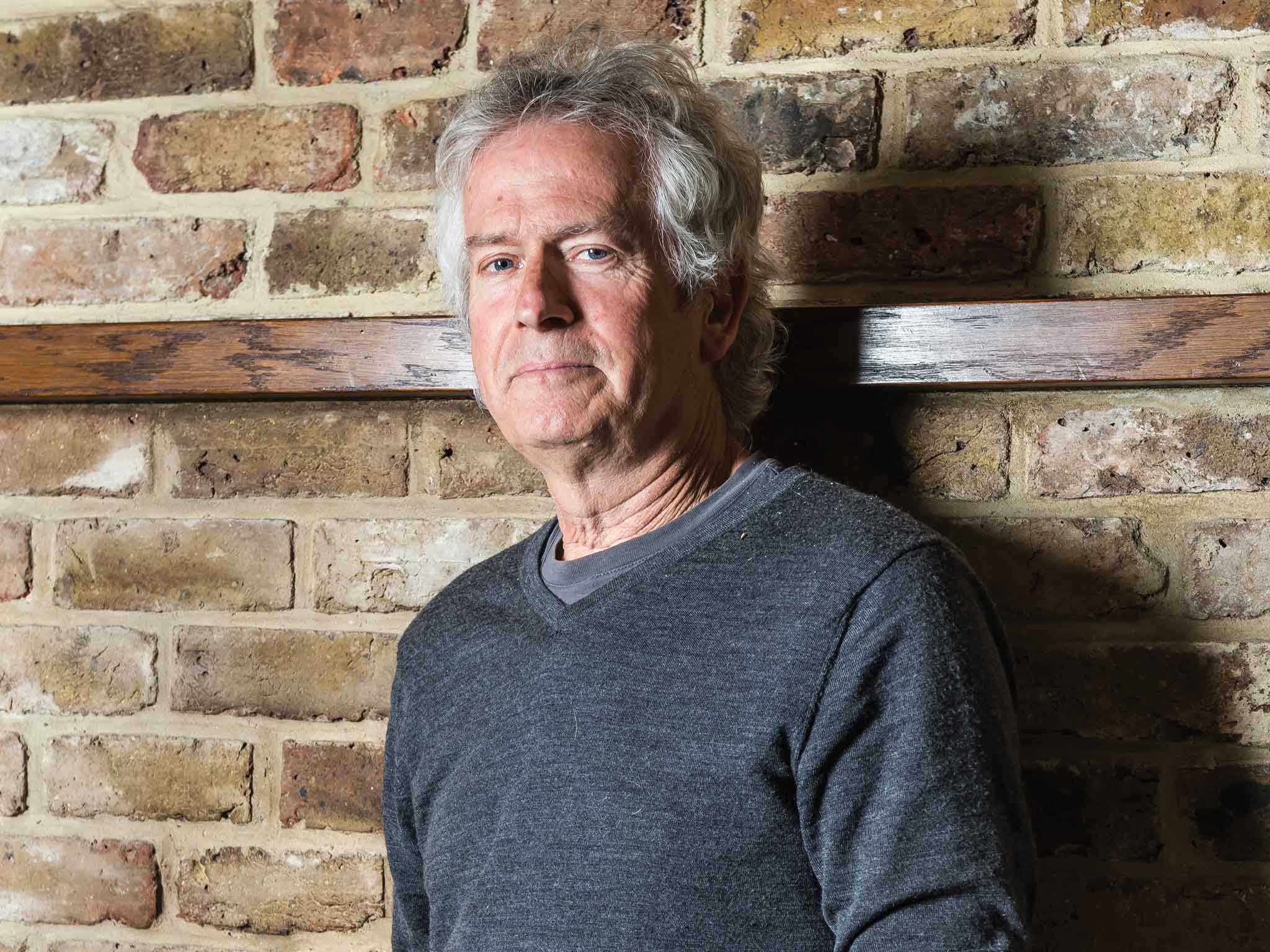

Lake recalls when he and Emerson toured together in 2010 there were some initial difficulties. “Keith had some problems early on, but once the tour got underway, it was actually a joy. We had a really good time. He was at his happiest certainly, when we were playing together. When we were playing it was all fine, everything was great. The problems began when we weren’t playing. When the music wasn’t the central point of his day, other things would take its place… he would dwell on issues and become unhappy and morbid.”

In the run-up to ELP’s final show at 2010’s High Voltage Festival, Palmer says the issues with Keith’s hand became evident. Though there was talk about the trio staying together in order to undertake a final tour following High Voltage, Palmer believes quitting when they did was for the best; something he says Emerson accepted, albeit reluctantly.

“We played a good show,” insists Palmer. “But it wasn’t something I wanted to be left with in my life. Maybe I was selfish, but I wanted to keep the dream that I had that ELP was great, and I realised I could only do that once. If I was to do that again it wouldn’t have been right. We had a dream and I didn’t want it to be diluted. We could do this once and people would walk away and say, ‘Wow, it was great!’”

Lake admits to being saddened the partnership hadn’t continued after High Voltage. “On an artistic front

I was disappointed, and for two reasons. One, is because of all the work we’d put into it in order to put that show up. But two, I think we owed it to the fans who bought all those records, after all those years. We should have gone out and played one last time. I said, ‘Look, we might not have been as great as we were (laughs), but here it is, you get a chance to hear the band one last time.’ And we’d show gratitude for the support we’d been given.

“So that side of it, I did feel a bit down about,” he admits. “It would have been good, because there was a lot of work to put it back to the point where it was. Carl was very uneasy, he wasn’t comfortable and I think it was probably best we didn’t do it. When someone’s not generally enthusiastic then it’s best to leave it alone.”

Without a shadow of a doubt Keith was the best musician I ever played with. Those first three or four years with ELP you’ll never be able to take away from me. They were absolutely superb.

Though most of us cannot claim to have known him to the degree to which those that worked with him, or called him a friend, the music Keith Emerson made on his own or in collaboration with others touched the lives of so many. The anguish we experienced at the news of his death and the very real sense of connection was as a result of decades spent listening to his music in rapt attention. That’s why we feel that gnawing loss. We’re so intimately familiar with almost every bar of every solo, we sometimes feel as though we know the artist personally. Emerson’s brand of magical thinking and creativity enabled him to fashion a rich legacy. While his music could be bombastic and full of compositional brio, he also wrote tunes of rare beauty and clarity. Had Keith lived, he might, as many hoped, transitioned to become more of a composer and conductor of his own work rather than a performer. Now, we are left to remember and celebrate his achievements in both of those roles through the body of work he left behind.

Carl Palmer looks back on ELP with great pride. “Without a shadow of a doubt Keith was the best musician that I’d ever played with,” he says. “Those first three or four years with ELP you’ll never be able to take away from me, they were just absolutely superb. The best thing about being in ELP was being with two other complete individuals that didn’t sit on the fence at any time, and whilst all of us were completely egotistical, and clashed all the time, when it came down to the nuts and bolts of what we were doing, the music always spoke the loudest. That’s why we were together.”

Though they’ve had their differences, it’s a sentiment with which Lake agrees. “I’d like Keith to be remembered for his achievements. ELP did have this reputation for squabbling but you know what? Fuck that! That’s not what the band was great at. It was music. That’s it.”

Why I’ll Miss Keith: Tony Banks

“Keith had a big effect on me. I recall going to see The Nice a couple of times at The Marquee in 1967, and watching him playing keyboards was an inspiration. It wasn’t just that Keith was an accomplished musician, which of course he was, but the fact that he was doing things nobody had ever done before. In that sense, his impact was comparable to that of Jimi Hendrix. He made me want to go out and play live.

“I only ever met Keith once, and that was at the first Prog Awards. He was very pleasant, and I remember whispering in his ear at the end, ‘You’ll always be a Prog God to me!’ As far as I am concerned, he was The Man.”

Why I’ll miss Keith: JOHN WETTON

“Underpinning the knives, the outfits and the showmanship was boggling technique and ability. Sure, Keith was an irrepressible exhibitionist, but do not let that obscure his bedrock genius, and a skill which took slavish dedication to hone.

“He was an immensely likeable man, quietly spoken, kind, generous and with a humility that showed itself in concern for the well-being of others. We spoke in depth several times over the last few months, and each time he would ask how I was coping [with cancer], and we laughed like drains at some seemingly trivial aspects of our common journey.”

Why I’ll miss Keith: GEOFF DOWNES

“It was amazing to witness what he did with The Nice, as he took keyboards into the domain which was usually the province of egotistical guitarists. His impact became even more apparent with ELP.Considering how outgoing and extroverted Keith was onstage, away from the limelight he was a very quiet guy, with no ego at all. There were no airs or graces about the man.

“Keith was a role model and idol for me. In terms of keyboard playing in a rock band, he was ‘The Man’. He achieved so much, but among his most important contributions was taking classical music and fusing it with rock.”

Why I’ll miss Keith: STEVE HACKETT

“I loved Keith’s style. He was extremely influential on a generation of keyboard players. He had a stunning technique, plus the chops and showmanship to put keyboards centrestage. He proved you didn’t have to sit there and play quietly in a corner. He had panache and was very entertaining, whether you were listening to him, or watching. Keith threw down the gauntlet to others. Visually, he has never been topped.

“On a personal level, he did a lot of good for Genesis whenwe needed help. He gave our Nursery Cryme album a nice review [for the press ads]. That made a big difference to us.”