It began innocently enough with a throwaway slogan in Sounds music weekly, way back in 1977.

But even though it was completely off-the-cuff, this telltale phrase unwittingly ushered in a brand genre of music. Indeed, what we are about to witness became something of a mantra in its own right.

Cue epic drum roll from resurrected guest star, John Panozzo… ‘Pomp rock lives – run for the hills!’

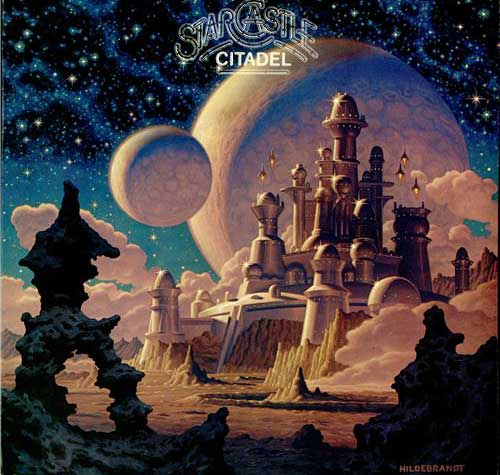

That epoch-making double-decker headline was written to accompany a dual Sounds review of Starcastle’s third album, Citadel, and a long-player by something called The Intergalactic Touring Band.

Before we go any further I’d better hold up my hands – immaculately manicured and moisturised, natch – in honest admission and reveal that I was the person responsible for both the Sounds headline and review. Having said that, I must admit I have no recollection of The Intergalactic Touring Band whatsoever (me neither – Ed). A quick bit of internet research reveals their sole release to be (and I quote) ‘a science-fiction pop-music concept album’ featuring Meat Loaf, Rod Argent, Larry ‘Synergy’ Fast and Annie Haslam of Renaissance fame, trying their damnedest amid a host of low-rent prog stars. Ho-hum. I reckon we can dismiss that one as an aberration.

But as far as Starcastle goes… well, now you’re talking.

Spearheaded by the spectacular, effects-laden work of Queen producer Roy Thomas Baker (who had honed his skills on Starcastle’s previous album, Fountains Of Light), Citadel is a sumptuous classic that thoroughly deserves its premier-league pomp-rock reputation.

Reading back my review more than 30 years down the line, I find it littered with telling phrases. ‘The harmonies are quite superb… the drum sound varies from a militaristic clatter to a throbbing undercurrent… mystical lyrics… instantly memorably hooklines… mouth-watering keyboard passages…’ et cetera, et cetera, ad infinitum.

Of course, back in the 1970s, ‘diet’ products were an alien concept; it’s only in recent years that Starcastle have been branded ‘Yes Lite’. But while Citadel does indeed owe plenty to Yes’ Close To The Edge, it’s a highly commercial and extremely accessible listen, not artsy-fartsy or daunting in the slightest. To cop another line from the original review: ‘This is music is made by warm, sensitive human beings and not vacuous vegetarians.’ Ouch!

So there you have it. Starcastle were the first band to be adorned – some might say lumbered – with the bombastic banner emblazoned with the words ‘pomp rock’. That fact is undeniable, irrefutable.

But before we go any further, we need to ask the all-important question: what exactly is pomp rock?

Classic Rock’s Malcolm Dome summed it up perfectly in a Buyer’s Guide to the genre: ‘American youth listened to the likes of Yes, Genesis, ELO and Queen, scratched their stubbly chins and thought: “Hmm… we can make something of this. But it has to be radio-friendly, and it also has to have serious musical values.”’

This crucial cogitation spawned a fresh crop of bands who adopted the progressive tendencies of Britain’s finest bands of the early 70s, and then added distinctive melodic rock-oriented sheens of their own. The new arrivals puffed out their chests and headed out to do battle, equipped with a formidable arsenal of high-pitched voices, high-faluting lyrics, big guitars and bigger keyboards.

As Dome put it in his inimitable way: ‘Pomp was the child disowned by prog and orphaned by AOR; the beast locked in the cellar who got loose to terrorise the neighbourhood.’

It’s difficult to argue with the two albums dubbed ‘essential’ in the pomp-rock Buyer’s Guide: Styx’s The Grand Illusion (1977) and Leftoverture by Kansas (1976). Elsewhere were the likes of Blue Öyster Cult (Agents Of Fortune, 1976), Angel (On Earth As It Is In Heaven, 1977) and Zon (Back Down To Earth, 1979).

Interestingly, only two British bands made the final cut: Yes with Going For The One (1977) and those melodramatic midlanders with the scuffed platform shoes: Magnum. Their debut 1978 release, Kingdom Of Madness, is still highly regarded among the pomp populace.

Magnum frontman Bob Catley tells us: “I looked up the meaning of pomp rock on the computer and it came up with something that wasn’t very complimentary. Apparently it’s all about balding old blokes and wailing guitars, high-pitched voices, too many keyboards… it sounds terrible. I don’t know if I’m a flag-bearer for that kind of music,” he laughs.

“Having said that, I know Magnum have been viewed as pomp rock in the past, especially with our early albums, even though we came out in the middle of the punk rock era.”

Catley agrees that Styx and Kansas are top examples of prime-time pomp: “Me and Tony [Clarkin, Magnum guitarist] have always liked those two bands, so maybe that came into play and they influenced us a little bit when we started out, I don’t know.

“Having said that,” he adds, “I’ve always been a big fan of Queen, and you can’t get more pomp than Queen, can you? Freddie Mercury is my ultimate frontman.”

But Queen always eschewed the use of keyboards – or synthesisers at the very least. Can you have a pomp-rock band sans keyboards?

“Hmm…” Catley considers. “I suppose keyboards are everything, if you’re talking about this kind of music. [Magnum’s] Mark Stanway is the king of the keyboards; he loves being the pomp king. Yeah, that’s a pomp rock band for me: huge banks of keyboards like Emerson, Lake & Palmer.”

But – and we’re sorry to throw another spanner in the works here (that being Works Vols. 1 and 2, natch) – ELP specialised in lengthy, classically inclined instrumentals; they didn’t have much, if anything, in the way of lead-guitar work. Where would a band like Styx be without Tommy Shaw’s melodic strumming and James ‘JY’ Young’s heavy metal crunching providing a critical contrast? Sheesh – it’s a pomp-rock conundrum, for sure.

Speaking to Vintagerock.com, ELP drummer Carl Palmer made a key pomp point: “When you look at it today, it’s rather ludicrous to say we were pompous, we were overblown. The shows we did then were overblown, but when you consider what’s being done today, all we did at the time was set an industry standard and hope people would improve on it. Unfortunately for the naïve people who are in the music business, they thought it was overblown and it was too big. We were just setting a standard.”

Derek Oliver runs Rock Candy Records, who recently re-released Starcastle’s Citadel album in remastered form. According to Oliver, there’s also a crucial difference between prog rock and pomp rock: “To simplify, you could say that prog was borne from classical and jazz music, and relied on dexterous musical ability with scant regard for structure – it was all about improvisation.

“Pomp, however, took prog as its starting point but then infused it with song structure, like The Beatles jamming with Yes. Sure, pomp could be as indulgent as prog with its complex arrangements but the central theme always suggested that a melody or hook wasn’t that far away. That, then, is the key difference.”

Oliver also has strong feelings concerning the ‘keyboard debate’: “A pomp-rock band should, in an ideal world, consist of at least five members of which the keyboard player and guitarist must engage in mortal combat during virtually every song. The presence of a keyboard player is prerequisite although the UK’s greatest pomp-rock band, Queen, proudly trumpeted the fact that synthesisers were not used in the creation of their albums.”

So that’s cleared that one up, then. We think.

You’ll have noticed by now that most of the pivotal pomp-rock albums were released in the years 1976 and 1977.

“There was a sort of rare musical alchemy present in the atmosphere during the mid- to late 70s,” Oliver believes, “a result of curious alignment of the stars and the realisation that progressive rock needed to advance one stage closer to the actual creation of songs rather than prolonged musical indulgence.”

So far, we’ve theorised that pomp bands took the prog ethos and injected it with accessible songwriting techniques. Styx, Kansas – and even the likes of Journey and Boston – all came from the same heritage and provided a soundtrack for America at a time when the punk-rock revolution threatened (but failed) to kill off the trad prog movement in the UK. Pomp, then, was an extension of prog. But like all great musical movements there was a built-in use-by date – 1981 seems to be the cut-off point.

“If there are any modern bands out there operating with the same sense of flamboyance as classic-era pomp rock then I’ve yet to hear them,” Oliver says plainly.

There might just be hope on the horizon. In my recent review in Classic Rock of Wintercoast, the new album by fast-rising British proggers Touchstone, I stated: ‘Spearheaded by Adam Hodgson’s abrasive guitar and Rob Cottingham’s swirling keyboards, many of the songs veer into pomp-rock territory. If I didn’t know better I’d say legendary Styx producer Barry Mraz was at the helm.”

While not disagreeing with the above comments, Hodgson insists: “I think ‘pomp’ is still a dirty and smirked-upon word. Where in the last few years prog has become acceptable again – the BBC are happy to run documentaries on the subject – pomp suffers from too many ‘cheese factors’.”

He has a point. But having said that, to many pomp connoisseurs the cheese is the icing on the cake. Or, more accurately, the toast.

I have vivid memories of the time I first encountered Styx, just after the release of their Equinox album in 1976. It was at a show in El Paso, Texas – a mayhem-packed affair with hordes of Mexicans in the audience lighting bonfires, even though was an indoor venue!

At the end of Born For Adventure (chorus: ‘I was born, born for adventure, women, whiskey and sin/No, I’ll never surrender/Live by the sword to the end’), Styx’s then-keyboard player, Dennis De Young, leapt on stage dressed as the archetypal dandy highwayman – cloak, mask, rapier, the whole caboodle – and proceeded to engage in a mock swordfight with a similarly attired roadie. Naturally, ‘JY’’s guitar screamed in torment, in tandem with DeYoung’s every stab, slash and swipe.

Yes, there might have been a whiff of cheddar back there in El Paso back in ’76, but it was pomp rock incarnate. Good and proper...

This article originally appeared in issue 3 of Prog Magazine.