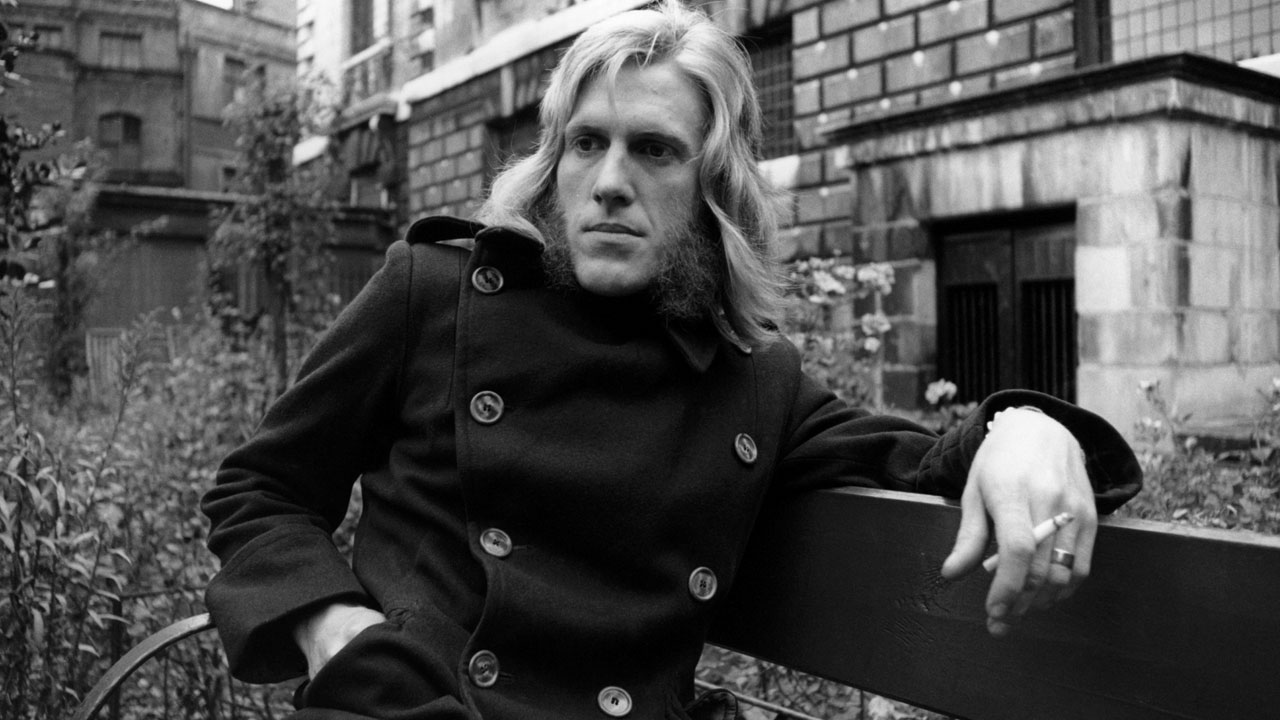

When pianist and composer Keith Tippett played you listened. Not a cursory, in the background while you’re busy with something else but more of a dumb-struck, stopped-in-your-tracks, type of listening that commanded attention and struck deep.

Whether it was at the helm of the his 50-strong Centipede orchestra, the atonal cluster-bombs notes pitched into King Crimson or his work with Ovary Lodge or Mujician, where the building blocks of music were forensically explored at an almost sub-atomic level, his was a unique, inquisitive musical voice, whose fluid virtuosity conjured elemental forces, stirred the passions and burned with heartfelt lyricism.

The son of a policeman, when Tippett moved from his native Bristol to London in the late ‘60s working in a factory to make ends meet.

“I was so romantic, I just thought I’d get off the train in London, bump into Ronnie Scott or someone like that and start playing in jazz groups. Of course it wasn’t like that,” Keith told me for the 2012 reissue of his 1970 debut, You Are Here I Am There.

Released on Polydor and engineered by Eddie Offord, it had been recorded a year earlier for producer Giorgio Gomelsky’s Marmalade imprint but delayed when the label went bust. By the time album eventually appeared Tippett had already carved himself a reputation as an incendiary soloist and as important compositional voice. His sextet on the recording including saxophonist Elton Dean, cornetist Mark Charig and trombonist Nick Evans had already been purloined to join an expanded live version of Soft Machine with Dean becoming a permanent member from 1970’s Third. Tippett himself would later briefly guest with a revitalised Soft Machine on tour in 2012.

If Tippett’s impact on the UK’s jazz world was immediate and direct, his influence on the burgeoning progressive rock scene was perhaps more subtle but striking nevertheless.

The next album, also in 1970, Dedicated To You But You Weren’t Listening, boasting a highly collectable cover by Roger Dean for Vertigo saw him expand his aural palette into rockier territory.

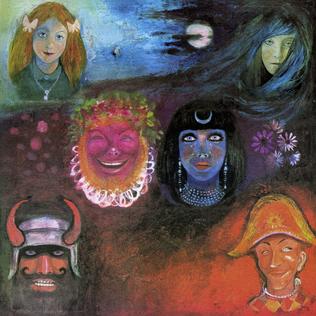

His group’s appearances in 1969 as part of the Marquee Club’s New Paths concert series of concerts which placed rock and jazz on the same bill, fostered links and connections that would propel his startling technique to a wider audience chiefly via his remarkable contributions to King Crimson’s In The Wake Of Poseidon, particularly his gleefully anarchic scattering of pointed notes hitting the surface of Cat Food.

King Crimson’s sole appearance on BBC TV’s Top Of The Pops, was with Tippett, miming Cat Food alongside Robert Fripp, Peter and Michael Giles, and Greg Lake. This somewhat incongruous convergence was listed in The Guardian’s series highlighting 50 key events in the history of dance music, praising Tippett’s “thrilling cascades of spiky dissonance to Fripp, McDonald and Sinfield's cynical, asymmetric art-rock.”

Nicholas Pegg’s encyclopaedic The Complete David Bowie acknowledges Tippett’s work with Crimson and this song in particular as an influence on Bowie when he brought pianist Mike Garson into the band, suggesting that Tippett’s playing “bears a striking similarity to Garson’s work on Aladdin Sane.

While his first love was jazz, Tippett was never a musical snob. He kept his ears open, always keen to see how his playing would sit in different contexts. He appeared on many sessions whose artistic breadth provides ample testimony to his eclectic spirit including ex-Fairport Convention’s Ian Mathews, Keith Christmas, Peter Sinfield, Arthur Brown, David Sylvian, Shelagh McDonald and others.

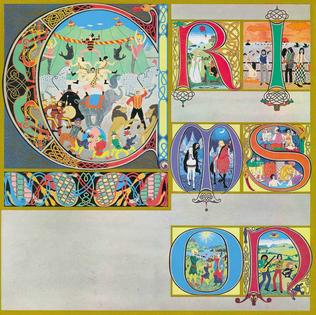

Tippett, along with his band members’ Charig and Evans would guest on King Crimson’s Lizard, and later, Islands. His presence on Lizard was so significant that Fripp asked Tippett to join King Crimson with the pair of them on equal footing when it came to determining the band’s musical direction. Though flattered, Tippett declined in order to follow his muse through jazz.

The relationship endured however with Fripp producing various Tippett albums including 1971’s Septober Energy by Tippett’s Centipede. An ambitious work spread across a double album, the fifty-piece ensemble included string players from the classical world, jazz and rock musicians, it featured contributions from members of Patto, Nucleus, Soft Machine, King Crimson, Blossom Toes and many others.

Wherever the band appeared in concert it garnered enthusiastic audiences and press alike, with RCA chartering jets to Europe and lauding Tippett as a leading composer and player of his generation. Mike Oldfield recalled in his 2008 autobiography, Changeling that seeing the band perform Septober Energy gave him the idea for an expanded suite of music flowing from one section to another.

Tippett’s most enduring partnership was with his wife, vocalist Julie Tippetts (née Driscoll). The pair first met in when Keith was brought in to provide arrangements for her first post-Brian Auger album, 1969 During the sessions they became romantically entwined and remained so ever since. Their musical connection was telepathic, and as a couple in performance, they made a formidable team just as they had done away from the stage.

“May music never become just another way of making money,” Keith was fond of saying, highlighting what he regarded as an almost sacred calling when it came to his music. In Europe he was well-regarded and worked their in various capacities. At home he was often involved in education at various music schools, inspiring new generations of players. Though well regarded in the world of jazz his lack of a domestic profile could occasionally niggle.

In one telephone conversation I had with him a couple of years ago he was irked after approaching BBC Radio 3 regarding a broadcast of his latest composition only to be told by the young executive he should send in a tape as an audition.

Though best-known in rock circles for his association with King Crimson, Tippett’s fifty-year recorded legacy is a treasure trove that rewards repeated and serious exploration. A giant of his generation, his loss is huge, not only to his wife Julie and family but to his extended family, those who joined him on his remarkable journey.