Iggy Pop claimed that he killed the 60s, but it turned out it was four semi-normal guys right off the streets of New York who really drove the final stake through heart of the peace-and-love decade nearly 46 years ago.

Gene Simmons, a former elementary school teacher; Paul Stanley, a cab driver with a heart-shaped face; Peter Criss, a sometime butcher and itinerant drummer who studied under the mighty Gene Krupa; and Ace Frehley, a gang member-cum-liquor delivery man. They stormed out of a $40-a-month fourth-floor walk-up in New York’s Chinatown in their six-inch platforms and sweaty black leather looking like four beasts disgorged from the underworld, and unleashed an unholy and entirely masculine creed of sex, braggadocio, innuendo and conquest, all delivered at a screeching 110 decibels and addressing every young man’s fantasies.

While the band’s message has changed over the years (they’ve become more family-friendly and forswear any cursing during the show), they still attract legions of foot soldiers into the Kiss Army – even now, when they’re calling it quits in one final tour they’ve dubbed the End Of The Road. (They’ve attempted to trademark the term with the US Patent office to prevent any other retiring bands from using it. Good luck with that.) So far, 44 shows have been played in North America, with another 25-date run beginning in August. The European leg begins next week, and there are plans to extend the tour until, probably, mid-2020.

Back at the beginning, the band were fuelled by high ambition, an unrelenting will, a prodigious work ethic and only the most rudimentary of musical talents. But they not only changed the face of musical history by painting it in Stein’s Clown White, they also kicked off their own brand of revolution, putting music back in the hands of the ordinary people and turning it back into a populist manifesto, picking up where Grand Funk Railroad left off by knocking rock music off of its lofty perch, stripping it of its perfect hair, wrecked cool and tight velvet stovepipe pants.

Prior to Kiss, rock stars seemed to exist in some distant Valhalla, breathing saffron-scented air, buying and wrecking Aston Martins, imbibing rare substances worth a king’s ransom and rarely consorting with mere mortals unless they looked like supermodels or Beatle wives. In short, rock stars were not like the rest of us.

But the members of Kiss were. They were a little unfinished. Outsiders, really, not the captains of the football team with a blonde cheerleader on their arm. Instead they more resembled the guy who sat next to you in Advanced Mathematics class. Meaning they were smart guys. Smart enough to know their history, and figuring out it was just about time for a sea change.

“It was the mid-seventies, and people had had enough of the hippie, political thing and just wanted to have a good time,” Gene Simmons explained a few years ago. In the early days, Paul Stanley was fond of saying: “We are our fans.” While not exactly true, it was an appealing notion. These days he’s altered it a little, saying: “Our fans may not look like us but they can feel like us. I think that in our own way we’ve motivated people to, in their own way, be Kiss. Whether it’s to become a writer, whether it’s to become a country singer, whether it’s to become an attorney, you name it.”

Maybe at the heart of it was that Kiss has always been more than just a band. It was a state of mind; a place where feeling alienated was venerated, where boys were men, girls were groupies and nobody ever had to turn down the volume. But there’s something compelling about the egalitarian ideal that anyone could do what Kiss did. Kiss weren’t obviously handsome, rich, cultured, preternaturally talented, advantaged or even art-school dropouts like their British counterparts, but the implied message was that, given the right circumstances and drive, anyone could become a rock star.

But to be accurate, self-empowerment wasn’t really their early mission. That was to be bigger than the New York Dolls!

“Yes, that’s true,” says Simmons. “I remember Paul and I went to see the Dolls play at a local thing in New York City. It was right at the beginning; they came about six months before us. Paul and I were in the back of the hall, and we had our big hair, trying to look cool, but nobody knew us.

“The Dolls came on stage and we said: ‘Wow, they look like real rock stars.’ Then they started playing, and we looked at each other and, so help me God, I might’ve said it to him or he might’ve said it to me: ‘We’ll kill ’em.’ You could see the lust and the blood running from our mouths as we vowed: ‘We’ll fucking destroy them.’

“They had the swagger and everything else, but they just couldn’t play or sing; no harmony, the guitar playing was deficient. But boy they looked good. So Kiss was designed consciously as: let’s put together the band we never saw on stage.”

By doing that, they created a band that no one else had seen on stage either. If you don’t count mid-career Alice Cooper.

“They’re a good band. All these guys need is a gimmick,” Cooper commented dryly about Kiss in 1974.

Kiss apparently took that comment to heart, and added more pyro, flash pots, fire-breathing and gushing blood. Frehley had a guitar that shot flames, and Stanley was one of the first artists to hurl himself into the audience – and damn the greasy face-paint slathering over everyone, which became a badge of honour for fans.

Audiences got them, but critics rarely did. Rolling Stone named them the Hype Of The Year in 1975, and legions of reviewers complained that they were “derivative”, “prosaic”, “simplistic” and mostly a joke, a band that catered to the lowest common denominator. It wasn’t until 2014 that Kiss made it to the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame, and then only after fans were allowed to vote.

They were always geniuses at self-promotion. Simmons had quite a bit of practice at self-invention, having emigrated from Israel to New York as Chaim Witz at the age of eight. He became Gene Klein, and began the task of turning himself into an American kid. So fraught with psychic landmines was he that turning himself into the God Of Thunder wasn’t even a stretch.

As for Stanley, he had no less gargantuan a task. “I was a fat, chubby, unpopular kid who disguised himself as a good-looking, cocky frontman in a band, and somehow turned into it,” says Stanley, who at 67 looks 20 years younger. “Hopefully we all find who we are and we become it.”

That self-actualisation, inspirational stuff came later – probably about the time he wrote his book, A Life Exposed, in 2017 – but there was a flicker of it around the time the Kiss Army started swelling in 1979. An incipient fan club, it started as a grass-roots affair in January 1975 by two Kiss fans. They would identify themselves as the President and Field Marshal of the Kiss Army when they called their local radio station to request Kiss records. By the end of 1978, membership in the Kiss Army topped six figures, with merchandise revenues of $100 million a year.

“We definitely tapped into something. And a lot of times we weren’t even aware of it, but we just kind of went with it,” Frehley admitted in 2014. “I always used to say when we were in our peak I felt like I was riding this roller-coaster and I was holding on for dear life. A lot of the things I did were just on instinct, whether it be my songwriting or how I dressed or things I did. Luckily I have good instincts.”

But that wasn’t really true of Stanley and Simmons. They always had a plan for domination – world and otherwise – and stuck to it. Which is exactly why they are winging their way on a private jet to Glendale, Arizona, for the tenth stop on this final tour – and Frehley and Criss are not.

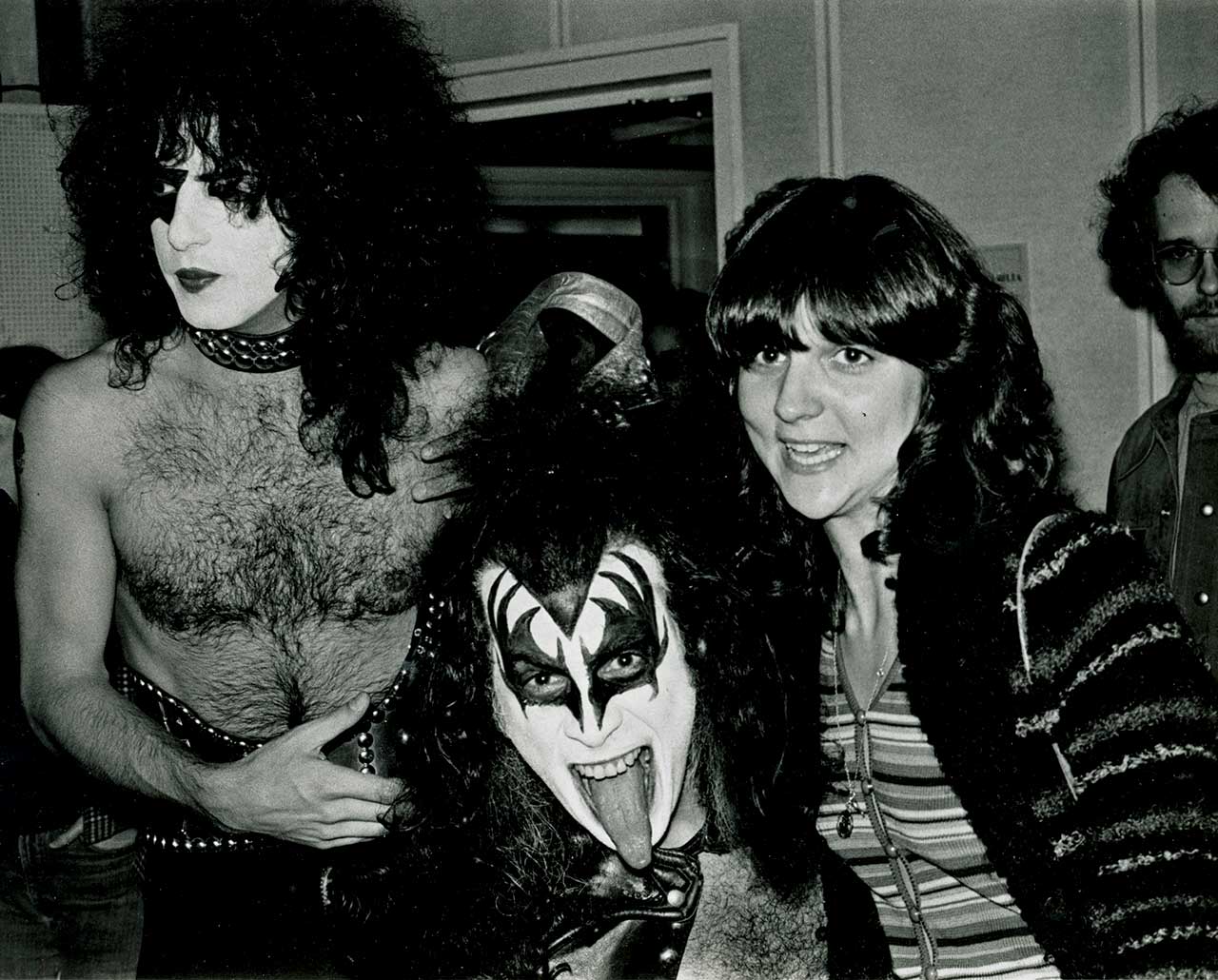

While a Kiss admirer, I wasn’t there at the beginning. And when I did come face to face with these nightmarish figures in wobbly platform heels, abundant chest hair and aggressive face paint, it was by sheer happenstance.

After covering a David Essex record-release bash on the heels of his hit Rock On, I found myself in New York with a free night. Renowned Bowie photographer Leee Black Childers had invited me to a panel he was shooting for NARAS (the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences) and promised dinner afterwards. I said yes, although it wasn’t because I was intrigued that the panel was titled Superstar Or Superstud. It was just the free dinner. I was hoping for the Russian Tea Room.

I was one of the first to arrive at Columbia Records’ Studio B. There were just a handful of people sitting on folded chairs in a small room that couldn’t have held more than 30 people comfortably, but most of the psychic space was already taken up by four looming creatures in fetish wear, looking like warlords from the underworld.

Criss wore a leather vest without anything under it, shivering in the windowless studio. Stanley was stripped to the waist, his chest hair curling menacingly, with a studded dog collar around his neck. Sitting next to him was Simmons, in more elaborate attire: a black leather jacket and pants with strategic holes cut out, and again a bare chest. Frehley was the only one fully covered up, in his futuristic spacesuit, his hair ratted out to there.

At the time, it was impossible to know who was who; they had all switched their nameplates, except for Criss, who didn’t have one at all – a metaphor that would play out over the course of his tenure in the band. But on that chilly October night, Paul Stanley was Ace Frehley, Gene Simmons was Paul Stanley and Ace Frehley, impersonated Simmons with aplomb, aided no doubt by the large gin and tonic in a clear plastic cup before him, something Simmons, a lifetime tee-totaler, would never partake of.

Other participants on this forward-looking panel about sex and gender in rock included Danny Fields, a zeitgeist spotter who had discovered Iggy And The Stooges, signed The MC5 to Elektra Records and would go on to manage The Ramones; Wayne/Jayne County, the first transgender rock artist, and part of the Warhol crowd; Jerry Brandt, manager of rock’s second transgender figure, the disturbing Jobriath; industry publicist Connie De Nave; and Richard Robinson, husband of celebrity wag Lisa Robinson and notable at the time for producing Lou Reed’s first solo album.

What struck me that night wasn’t the all-industry star-power gathered in a small room, but that each time the panel mediator, DJ Alison Steele, asked something of the members of Kiss, their reply was: “It’s only rock and roll, but I like it,” no matter what the question. Every single time. They had the sheer bad-boy audacity to not only not do what was expected of them, but also to flaunt it in the faces of what was then the music-industry glitterati. It was chilling how they never broke character once, no matter how awkward and non-sequitur their canned answer was. These were monsters who oozed out a collective nightmare, and they were hell-bent on staying that way for the entire duration of the hourlong panel.

Somewhere around the 20-minute mark, I knew I had to get them into the pages of Creem magazine, where I was a senior editor. I thought they fitted right into our rebellious, there-wasn’t-a-rule-we’d-obey, fuck-you-if-you-can’t-take-a-joke aesthetic.

It appeared I was the only one who thought that way. “They’re New York Dolls clones,” my fellow editor Lester Bangs said dismissively. “Comic-book trash,” spat Dave Marsh. “If you want those clowns in Creem, you’re the one who’ll have to write it,” warned features editor Ben Edmonds. “And it better be fucking good.”

No matter the derision from my colleagues, I knew I was on to something. Recalling that old saw from Victor Hugo written 121 years before Kiss had ever picked up their first tube of lipstick – “There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come” – I was sure that idea had arrived, and that it was wearing black leather.

That’s how I found myself a month later with a craft knife in my hand, sitting in front of a pile of photographs of Kiss in make-up and civilian clothes. In out-takes from the Dressed To Kill album cover, the band members were posed hiding their faces behind newspapers, piling into a phone booth in their suits and ties and then coming out in full regalia, emerging from a subway with fists flourished, performing Herculean tasks in which these four not-so-superheroes saved the world from bland music by sabotaging a John Denver concert. I not unexpectedly titled it ‘Kiss KOMIX’. With that knife, I carved out a dubious niche for myself as the unofficial Kiss Editor.

Over the decades I have continued to monitor that long-standing beat, although I have to say that when I look back I find I miss the era when Kiss were dangerous, inscrutable, inappropriate and just badass.

There was a mystique about the band in those days. Stanley used to say: “I think we get so many groupies because everyone wants to fuck their fantasy or their nightmare. Someone in leather and make-up fucking you must be pretty strange.” It makes one wonder how many times the band members engaged in coitus while suited up.

“It was God Of Thunder, from Destroyer, that turned me on to rock’n’roll, because Gene Simmons sang it,” remembers Babes In Toyland’s Kat Bjelland. “It sounded heavy, mean and evil. Like his soul was being ripped out of his chest. It gave me the shivers.”

Those were the days when Kiss were never photographed out of make-up, and kept bandanas in their pockets to quickly cover their faces in case lurking photographers actually figured out who they were.

In 1975 I slapped on my own Stein’s Clown White make-up, studded cuffs, black leotard, plastic-encased spider-belt buckle and seven-inch stilettoes, and strapped on a red Fender to perform with the band during Rock And Roll All Night in front of 5,000 fans and the members of Rush. Never mind that my guitar wasn’t plugged in, I still got to feel what it was like to be a member of Kiss – or, as I noted at the time, that I was one-fifth of a sadistic cheerleading squad (although Stanley swore I looked like Minnie Mouse!). I called the piece I Dreamed I Was On Stage With Kiss In My Maidenform Bra, after a long-running print ad that depicted women in their underwear waking up in unusual places. But certainly none were more unusual than on stage in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, with Paul, Gene, Ace and Peter.

The next morning after the show, we all said our goodbyes and Simmons offhandedly said to me as I walked out: “Whenever you feel like putting on the make-up again, give us a call.”

Which is how I found myself 44 years later in their G-4 Gulfstream private plane on a late afternoon in February, the day before Valentine’s Day, sitting across from the God Of Thunder.

“You still wearing your Maidenform bra?” Simmons greets me as I walk down the narrow carpeted aisle of the plane. He’s much more understated than years past, his face unlined, wearing a pair of black track pants, a long-sleeved denim shirt with three buttons undone, his trademark black wrap-around sunglasses that he wears day or night, a black oversized hoody, his immovable hair tied back and tucked up under a black baseball hat emblazoned with the money bag logo – which he holds the trademark for, along with his signature where the two ‘S’s in his name are money signs. Simmons has applied for more than 182 trademarks including ‘Nude Car Wash’, ‘Trophy Wife’, ‘Sextacy’ and simply ‘?enis’. Of all of the ones he’s tried to register, he’s succeeded 44 times. And yes, he did score ?enis!

Even in a #MeToo era, Gene Simmons will always be Gene Simmons. Although recently he has had to pay the price, because the times are different and he realises that he needs to move with them. There are few public incidents, like the one in 2001 when he appeared on Terry Gross’s PBS Fresh Air radio show, telling the august radio host: “If you want to welcome me with open arms, I’m afraid you’re also going to have to welcome me with open legs.”

But in 2018 Simmons settled a lawsuit with a DJ in San Bernardino, California, who accused him of sexual misconduct during a November 2017 interview promoting Rock & Brews (a chain of restaurants Simmons and Stanley co-own), claiming he took her hand and kept depositing it on his knee, and peppered his answers with sexual innuendo.

That came only weeks after Simmons was reportedly banished from appearing on Fox News owing to “inappropriate and sexist antics” during an office visit. In response to the ban, he issued the following statement: “While I believe that what is being reported is highly exaggerated and misleading, I am sincerely sorry that I unintentionally offended members of the Fox team during my visit.”

“Yeah, these days I don’t even order room service if I’m by myself. I always need a witness,” reveals Simmons, shaking his head and appearing genuinely hurt. But not especially contrite. “

"I cleaned your pillowcase for you, Gene,” coos a leggy flight attendant named Kate who is poured into her tight black shirtwaist dress embellished with her name and a very subtle Kiss logo. “I couldn’t get the stain out,” she pouts.

“Oh, that’s okay. We’re men,” replies Simmons, puffing out his chest a little. “He likes to be dirty. In more ways than one,” says Eric Singer, who overhears the flight attendant as he walks into the plane, settling in his seat. Drummer Singer has been the Cat Man in the band since 1991, after Peter Criss’s replacement, Eric Carr, died of cancer.

The innuendo about Simmons isn’t as pertinent as it used to be. A rock Lothario who claimed to have had sex with 4,987 women (and had the Polaroid photographs to prove it), Simmons has been married to Canadian actress Shannon Tweed since 2011 and has given up all that.

“My schmeckle has been in a jar on the mantle for the past eight years,” he jokes. “Seriously, not one other woman since I’ve been married,” he says, emphasising each word.

Although it doesn’t prevent him from looking.

“I like girls,” he says ruefully. Later, when a stunning blonde named Shana sidles up to him backstage at the venue, he shakes his head with exaggerated remorse, pointing to his wedding band and saying: “Too late.”

“Is there anything I can get for you?” the fetching Kate asks Simmons as she reappears, balancing a small tray with an array of pastries and chocolate confections.

“I think I’ll have the chocolate coffee cake,” he says. “I’ve always been a sucker for chocolate.”

“I remember,” I add. “But that one time you got more than you bargained for,” referring to the time when I accompanied Simmons to a post-Kiss show bash the promoter had thrown for the band in ’74, after they broke attendance records previously held by Elvis Presley at Cobo Hall in Detroit.

“You were there with him?” asks latter-day guitarist Tommy Thayer, who began with the Kiss organisation after his Portland-based band Black N Blue disbanded in 1995. “We’d heard that story a hundred times, but we never knew that there was a witness to the first time Gene got high!”

“We weren’t even sure it was true!” adds Singer.

“So what was it like?” demands Thayer.

“‘Dazed and confused’ doesn’t even begin to cover it!” I say, laughing.

“What does?” asks Singer, urging for more, like a kid pleading for a bedtime story.

It was the promoter’s birthday as well as a party for Kiss, so there was a giant birthday cake. But after it was cut, waitresses made the rounds with plates of chocolate brownies.

“Don’t even think of having any of those,” I cautioned Simmons.

“Why not? I love brownies,” he replied, a little querulously.

“I know you love brownies. But just don’t. They’re hash brownies.”

“Hash brownies?” He looked bewildered, as if trying to figure out why anyone would want to defile chocolate with drugs.

Deciding to disregard anything I had to say, he took a fistful of the brownies and devoured them. Three big fat ones, dusted with powdered sugar.

“It was six brownies,” Simmons chimes in.

“It was three,” I replied. “One would have put you over the top.”

And that’s where he remained. Once the THC reached his bloodstream, it was like being with ET tentatively discovering the wonders of planet Earth, complete with long fingers outstretched to touch ordinary objects.

“Are my feet as big as I think they are?” “Does my head look funny? Is it really small?”“ Why are my hands so big?” “Are my teeth shiny?” he worried, running a black chipped nail up and down over his front teeth.

After leaving the party, on the way to the car he came out with a steady stream of questions, the border between what he was thinking and saying out all but demolished.

“I need milk!” he suddenly bellowed, I’m sure louder than he meant. The driver seemed alarmed, but pulled into the only store that was open in Detroit’s inner city. Which by no means made it safe. More than a little seedy, it was inhabited by winos, late-shift workers and ladies of the night. When we entered the place, Simmons said in a carefully articulated but booming voice: “May I have a glass of milk, please?” I remember the man behind the counter as if it were yesterday. “We don’t sell glasses of milk, son.”

“I don’t remember that,” says Simmons. “Mostly what I remember was how proud I was of the size of my… er, manhood.” “Funny, I don’t recall that at all. But then I didn’t have any brownies.”

“I ’m not sure it’s hit me yet that this is the end,” Thayer says, after the plane is airborne. “After it all winds down, I bet that’s when fans will finally accept me,” he says laughing. “Or maybe miss me.”

A genuinely nice man, Thayer is the bridge between the rock gods and mortal men. He started out a Kiss fan, cutting out photos of the band from rock magazines when he was 14, a skill that served him well when, after his previous band Black N Blue broke up, Simmons and Stanley asked him if he would consider being the photo editor for their 440-page, eight-and-a-half-pound behemoth photo book KissTORY, which was published in 1995.

“The first time I ever saw Kiss was in the back pages of Circus magazine in 1974, and I thought they looked amazing,” he recalls. “I’d sit around with my friends and draw pictures of Kiss.”

After KissTORY came out, the band kept Thayer on, promoting him to tour manager when the one they had quit.

He re-taught Frehley and Criss their parts when the original band re-formed for the first reunion tour in 1996, and was on hand when the 2001 reunion tour fell apart. It was then that Simmons and Stanley asked him to become a permanent member of the band, much to his surprise.

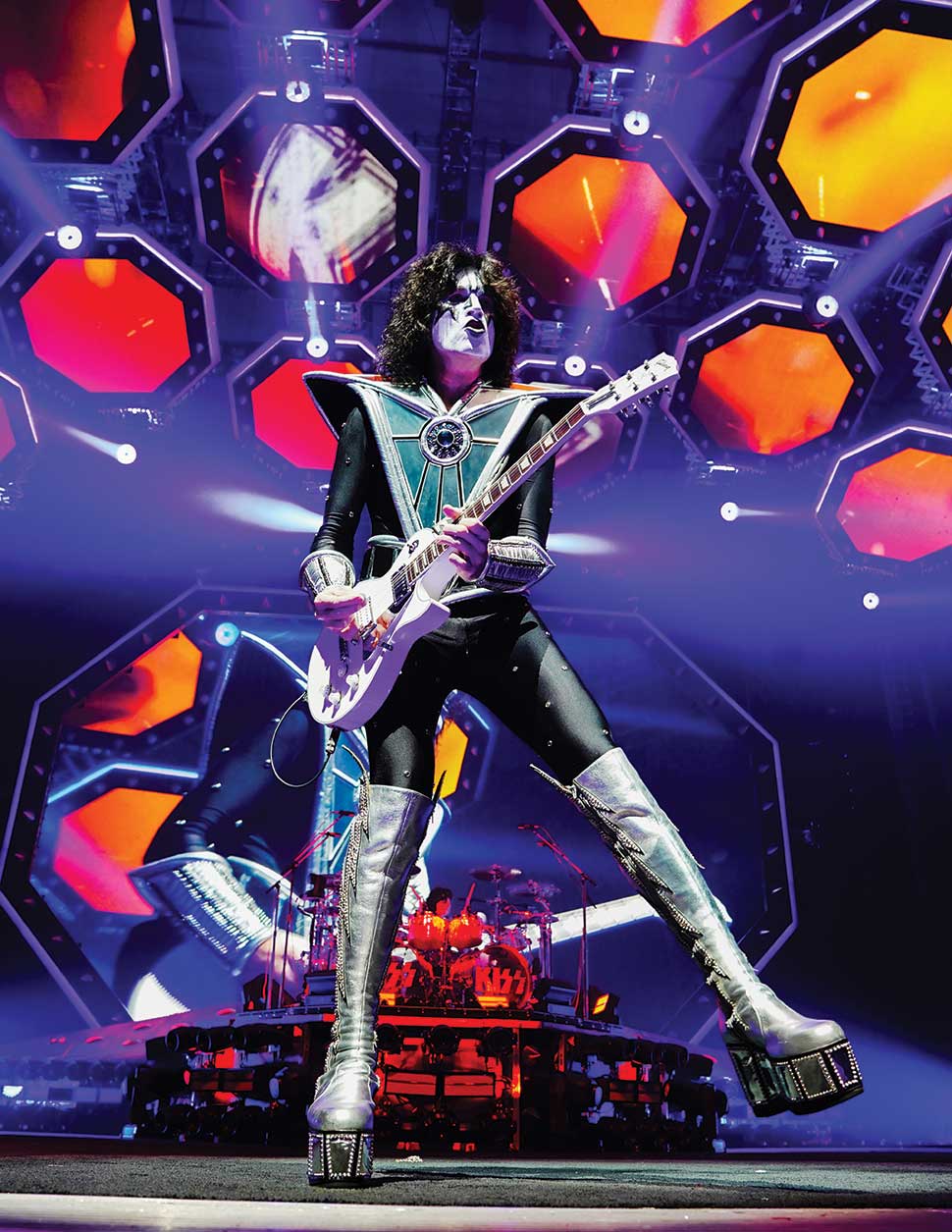

“When I’m on stage being the lead guitarist in Kiss, it’s a special place to be, because this is what every kid in the world dreams about doing and I’m the one that’s up there doing it,” says Thayer, at 57 the youngest member of Kiss.

"Tommy is so nice it reeks,” Eric Singer says, laughing. “Paul and Gene call him Switzerland, because he usually just takes the middle ground on things.”

“That is what they call me,” Thayer says when I look sceptical. “Paul usually sits in the back of the plane and Gene sits in the front, and I’m always in the middle, and I’m the intermediary. Sometimes I think I’m the glue that holds things together.” He stops suddenly, as if he’d said too much.

While Simmons and Stanley insist that they have never been on better terms, they still ride in separate SUVs en route from the plane to the venue, and when they line up for photos at the meet-and-greets with fans the two never stand next to each other.

“I think Gene and I feel much closer now,” insists Stanley. “Well we weren’t always, of course. You know, ‘old too quick, wise too late.’ But there’s really very little that’s worth fighting about any more. There’s a whole lot to be happy about. If there ever was a war at times… ” he pauses a beat too long. “The war is over. Everything’s good. We won.”

“When Paul and I met we recognised certain things that we had in common and other things that we didn’t,” Simmons says later. “He’s the brother I never had, and all those sorts of sound bites, but it’s kinda true. And I know it’s the same for him. What’s most different is we have slightly different points of views about stuff. I think I’m more infatuated with myself than Paul is,” he adds with a show of candour.

Stanley clip-clops out of his dressing room in his war paint, costume, heavy linked silver choker, truly magnificent mane of black hair and his heavy platform boots, picking his way around the tables of food to meet with David Butuk, Yvette Butuk and Ron Johnson, tonight’s Ultimate Fans from nearby Phoenix. For upwards of $6,500, fans can buy passes to meet their heroes, try on their regalia and chit-chat backstage with them. And now there’s a bittersweet aspect to the Ultimate Fan Experience, because this will be the final time Kiss will be in their city.

Stanley walks up to the trio; at six-foot-eight in his platform boots he looms over them. “Without you, there’s no us,” he says, with such sincerity and conviction it’s hard to believe he’s said the same thing probably 10,000 times. Yet still it’s affecting.

They pose for photos, Stanley wrapping a comradely arm around them, holding it there longer than he has to. He moves from that group to visit with a man whose son went to school with his son Evan, and then talks to a little girl who is eating a bowl of grapes and asks her for one. She complies, stretching a tentative hand towards Stanley’s scarlet mouth.

“Where’s everybody else?” Stanley asks after a while, looking around for his bandmates.

“Well, the first is the best!” he chortles, in a moment of transformation when you hear his indoor voice beginning to merge with his higher-pitched stage voice. “You got the meal, next you get the salad,” he says, and one immediately knows he’s talking about Simmons – primarily because none of the Ultimate Fans ever ask to try on Thayer or Singer’s boots or have personal photos taken with them.

Simmons finally emerges from his dressing room in the bowels of the venue a much more harrowing presence than the other three. His costumes are more elaborate and nightmarish, the mammoth boots seemingly pulled from some Chinese warlord’s tomb, but his trademark topknot is not his own.

“That is a tremendous-looking ponytail. It can’t be your own hair,” I say before I think better of it.

“The answer is that the top half is an extension,” Simmons answers unabashedly. “The bottom half is me. And the reason for that is because I sweat like a pig. If it was just my hair, then it gets wet and falls down. It’s hair-sprayed a lot so it stands up. But about forty per cent of the topknot is fake.”

“Just out of pure unabashed curiosity, since you answered that, when you meet someone can you tell they’re a Paul person, a Gene person, an Eric person or a Tommy person?” I ask Simmons after he’s posed with the three Ultimate Fans backstage. While not as touchy-feely or sincere as Stanley, he does make sure the Ultimate Fans have a memorable experience.

“When I meet fans? Yes. They’re a certain body type and personality type. I’ll answer, but it’s horribly sexist: male or female?”

“Both, of course.” I answer.

“The big guys like me. The sort of guys who are more in touch with their feminine side, more stylish and so on, like Paul. It’s difficult to get a big football player who goes for Paul. I’ve noticed over the years they react to my sort of overtly heterosexual blah-blah-blah. In the past, people have thought that Paul was gay. And he’s okay with that. But don’t kid yourself, Paul isn’t gay. But he’s clearly comfortable wearing red lipstick and prancing around the stage or smacking his butt and all that. I’m not. Eric and Tommy get Kiss fans who appreciate them being in the band, but it’s less about personality.

“As for females, the very pretty, model-y, attractive, thin, stylish women really like Paul. The very large-breasted, rounder ones love me. Some thinner ones, too, but mostly it’s the healthier women.”

“By the way, don’t I owe you one of my paintings?” Stanley says to me as he passes me in the hall. I wrote a piece on Stanley for Classic Rock in May 2017, and he told me if he liked the story he’d send me a painting of his that I’d admired on the wall of his Beverly Hills home. I just thought he didn’t like the story.

“I promise I’ll send it when we get back home. It was the Jester, right?”

“Yes, the Jester. Do you have to like this story too before you send it?” I ask unnecessarily – since I already know the answer.

“Yes.”

An accomplished artist whose paintings sell for $10,000 or more, he’s currently finishing a self-portrait and paintings of his band members in make-up. He shows me a recent photo of one he’s finishing of Jimmy Page in the famous white satin zodiac suit he wore on stage during Led Zeppelin’s 1975 tour. While he’s sent Page a few of his paintings over the years, beginning with a haunting portrait of Robert Johnson titled ‘Crossroads’, it’s unclear whether this one of Page will remain with Stanley or not. It’s impressionistic, yet captures the dark fire and even darker secrets in Page’s angular face. Stanley has an uncanny ability to paint the inner person, with an almost supernatural insight, elevating his paintings from mere portraits. Is it too simplistic to think that that comes from wearing all that make-up and those elaborate costumes for the past 45 years?

“You do know we don’t call them costumes,” Thayer tells me with a short laugh, when I ask him about a blue stone embedded in the breastplate of his regalia.

“Oh, sorry.”

“Maybe they used to call them costumes,” he continues, warming to the subject. “But now we call them outfits. It feels more genuine that way or something.

“The new outfit was a conglomeration of several people. I think it really makes a statement, almost like an Iron Man kind of look, especially during the guitar solo – all of a sudden there’s a beam of light coming out of the chest, a real superhero kind of vibe.”

Which begs the question:, when did Kiss actually get that promotion, elevating them from antiheroes and sex villains to superheroes?

“We’ve been able pretty much consistently to keep going for about forty-five years,” says Stanley. “The longer you can continue and the longer you can remain seemingly ageless, the more omnipotent you become. You take on the aura of superhero because you don’t age, and you continue to maintain the same point of view. When I go out in the crowd on that zip-line, there’s this sense of being invincible. And that feels good. And in the end, to be Superman with a guitar isn’t nothing.”

"You wanted the best! You got the best! The hottest band in the world!” booms the familiar introduction that’s begun every Kiss show since 1975. The sound reverberates through the thick concrete walls of the Gila River Arena, 43 years and 24 miles from the first time Kiss fired up their first flash-pot on an Arizona stage back in 1976. Nearly 19,000 of the Kiss faithful are gathered here as four metal discs that look more than a little like flying saucers are lowered from 150-foot rafters, depositing the quartet on their elaborate stage like invaders from a distant planet. Which in most ways they are.

A Kiss show has been a spectacle since early days, but on this final run the pyro is bigger, the blood more excessive (these days it’s a mix of raw eggs, yogurt and food colouring), the effects more mind-boggling (it takes 17 trucks to haul the gear from city to city) the hydraulics more sophisticated. But through all the changes of equipment as well as band members, there is something reliably predictable about a Kiss show that transcends time, tastes and epochs, tapping into something almost religious, something taboo and tribal.

“How ya all doin’?” Stanley asks in his stage voice, pitched half an octave above his normal speaking one. He minces across the stage, a swashbuckler in black, a beautiful creature with sinewy arms and only the smallest hint of a stomach under his cut-out glitter-and-fringe vest. He dives into the first familiar chords of Detroit Rock City, beginning a two-hour, 20-song victory lap through the band’s signature anthems, including such fan favourites as Shout It Out Loud, Deuce and Cold Gin.

“We’re gonna play all kinds of stuff for you!” screeches Stanley. And he’s right. Little is ignored as the band careens and mugs through the 70s and 80s with Psycho Circus, War Machine, Lick It Up and the disco-tastic I Was Made For Loving You. They even sneak in the little-played but stellar Say Yeah from their nineteenth album, 2009’s Sonic Boom.

Three-quarters of the way through the set, Stanley asks: “How about I come out and see ya?” He leads both sides of the auditorium in a bidding war to see where he should go, before snapping on a harness and zip-lining to a platform behind the sound desk to perform two songs facing the front of the stage. “This is a cool place to be,” he enthuses after the song finishes. “Because I can see Kiss!”

What he could also see, if he looked more closely into the faces of the audience waving, pointing and jumping up and down to get his attention, are the tears streaking many of the made-up faces. Even if Stanley claims that this last run isn’t bittersweet, only sweet, most of these fan-faithful would disagree.

“Everything in life is a cycle,” says Eric Singer, on the plane back to Los Angeles after the show. “Naturally, you have to complete the circle. I remember Gene and I were sitting in Las Vegas looking at the stage set-up. Gene looked at me in a moment of reflection and said: ‘You know, it really is time.’ And he’s right. It’s a lot of hard work to be in Kiss. It takes a lot out of you. I’ll be sixty-one this year, Gene will be seventy, Paul is sixty-seven. Tommy will be fifty-eight. We’re not kids. All I can tell you right now is I won’t miss anything. Not at all.”

“What will people miss when Kiss is gone?” Simmons asks rhetorically. “If you take it in the context of life as we know it on earth, there’s not a whole lot that’s important. You have brave men and women who put on uniforms and go to fight wars to protect freedom and die on the battlefield, and that’s a real thing. So in that context we’re not very important. Kiss is sort of like sugar. On one hand, sugar is fun, tastes good, and makes you happy. When you stop sugar, you’ll miss it. Maybe that’s what it is,” he says quietly.

“But I do know we raised the bar in terms of what you can expect now from bands. I don’t care if you’re McCartney or the Stones, you’ll have fireworks at your shows. And that’s because of Kiss, not Air Supply. That’s our contribution. When that’s gone, that’s gone.”

After the final confetti has been shaken loose and all the make-up has been sponged off, and all the equipment and hydraulics have been put back into their cases and hauled out to the waiting trucks, we file through the cavernous door of the Arena to a convoy of cars waiting to take us back to the private airstrip where we’ll board the plane for the trip back to Los Angeles. By now it’s after midnight and officially St Valentine’s Day – a rather Kiss-tastic holiday.

Taking advantage of the theme, the crew have decorated the cabin of the plane appropriately; small trays have been ornately set up with pristine white china plates, crystal goblets and snowy white tablecloths. An array of treats are scattered artfully over the tables: foil-wrapped chocolate truffles, little sugar hearts, a single red rose. Containers with the dinner we all ordered are now set in the middle of each tray. Additional rose petals are strewn across the trays, but in the turbulence during the flight some of them have fallen on to the plane’s carpeted floor.

About to open up my container, I see Paul Stanley making his way toward the front of the plane. I figure he’s coming to sit down at one of the tables. But it turns out that’s not on his mind.

“Pick up those petals!” he admonishes, frowning as he looks down at the rather tasteful grey flooring. “They’ll stain the carpet.”

Taken aback, I think he’s kidding, and start to giggle, but clearly he is not. So I bend down to gather up the errant petals and catch Tommy Thayer’s eye and try very hard not to let the hint of a laugh escape. While Stanley’s demand is a little obsessive, like Captain Queeg and the strawberry incident from Caine’s Mutiny, it’s also very telling.

“We’ve got this plane for a long time, why not keep it looking good,” he says.

Which is pretty much what he has done with Kiss for the past 45 years, finally bringing them down for a landing sometime in 2020.

“I think Paul is the driver of the car,” explains Tommy Thayer, strapped back in his seat after all the petals are picked up.

“It’s like you all have to be in the same car. You all have to be going to the same destination. That’s how bands work if you’re going to maintain some level of sanity and success. But there’s only one steering wheel, and I don’t care if you’ve got a fucking eighteen-wheeler or however many people in your band, only one guy can drive the car. And that guy that mans that wheel has to really not only know how to drive that vehicle, he’s also got to know the road that he’s navigating.

“Gene is the engine. Or maybe the gasoline,” Thayer continues. “No, I think Gene’s more the fuel,” he decides. “Gene is the fuel that helps drive that engine.”

“Gas?”I offer, with a laugh.

“I did not say that,” Thayer counters, a little tartly. “But the thing is, both of them got us where we are now. The only sad thing, now, when it’s almost over, is that people have stopped thinking of me as the new guy…” he says, staring out of the window into the darkness over the Arizona landscape 30,000 feet below…

The European leg of Kiss's farewell tour starts on May 27. Tickets are on sale now. This Classic Rock Kiss special is out now