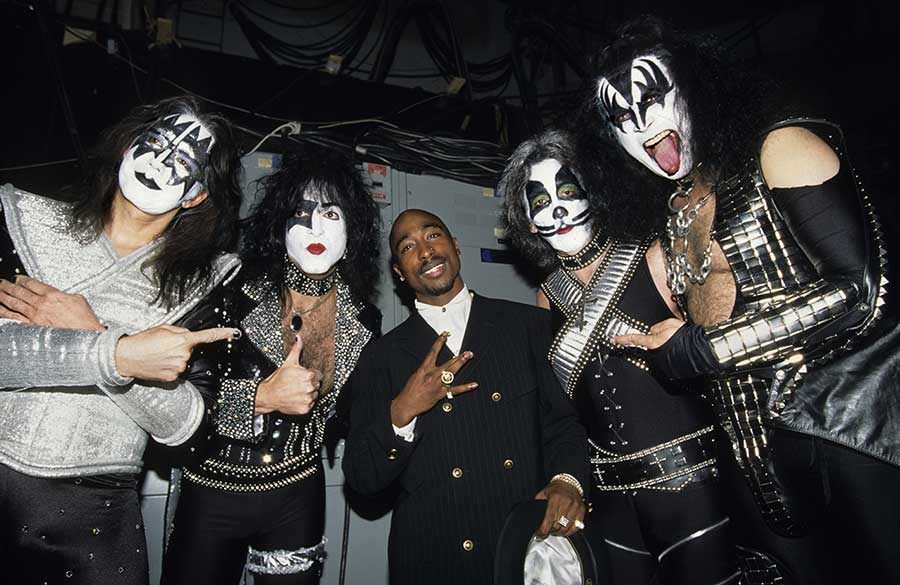

It was Tupac Shakur who broke the news every Kiss fan wanted to hear. The gangsta rap superstar was one of the high-profile presenters at the 38th Grammy Awards, held in Los Angeles on February 28, 1996. Taking the stage in a Versace suit and Death Row Records medallion, Shakur quietened the audience to make an announcement.

“You all down with this?” he said. “We’re gonna try to liven it up. You know how the Grammys used to be all straight-lookin’ folks with suits, everybody lookin’ tired, no surprises. We tired of that. We need something different; something new. So let’s shock the people.”

From the side of the stage strode a quartet of towering figures in stack-heels and make-up. This was Kiss – specifically it was the four men who had started the band more than four decades ago: Paul Stanley, Gene Simmons, Ace Frehley and Peter Criss, on the same stage in full costume for the first time in 17 years.

They were at the Grammys to present the award for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group With Vocal. They didn’t say much, but then they didn’t need to. This was Kiss letting everybody know that the Hottest Band In The World were officially back. But in typical Kiss fashion, it was never going to be smooth sailing.

Kiss had exited the 1980s shakily. Their two most recent albums, 1987’s Crazy Nights and 1989’s Hot In The Shade, were pallid pop-metal affairs held together by sheer willpower on the part of Paul Stanley. But worse was to come.

In 1990, longtime drummer Eric Carr was diagnosed with cancer of the heart. Sadly he lost his battle with the illness and died on November 24, 1991 – the same day as Freddie Mercury. It was a blow, but there was no way it would stop Kiss. Stanley and Simmons considered replacing Carr with Aynsley Dunbar, the veteran drummer who had played with everyone from David Bowie to Journey, but decided he was too high-profile.

Instead, they recruited Alice Cooper sticksman Eric Singer, who had toured in Stanley’s late 80s solo band and stood in for Carr on Kiss’s cover of Argent’s God Gave Rock And Roll To You, recorded for the soundtrack of the 1991 comedy movie Bill And Ted’s Bogus Journey.

“Some fans thought that we were insensitive,” said Gene Simmons. “‘How could the band continue, why didn’t you love him?’ But they weren’t there. They’re not qualified to say."

Singer’s first album with Kiss was Revenge, a record that, like Creatures Of The Night a decade earlier, was designed to reposition them as a back-to-basics rock band. Produced by their old associate Bob Ezrin – the man who had helped steer 1975’s Destroyer to greatness – it was their most focussed album in years, and their heaviest.

This new approach was best summed up by lead single Unholy, a menacing slab of modern metal with a scowling vocal from Gene. Unexpectedly, that was one of three tracks co-written with former Kiss guitarist Vinnie Vincent, who had left acrimoniously in 1983 and spent the ensuing years in a war of words with his former employers. But Unholy was no fluke, as Stanley’s salacious Take It Off and Simmons’ lecherous Domino proved. The concluding drum solo, Carr Jam 1981, was a tribute to their fallen bandmate, while the album itself was dedicated to Carr.

“It’s time to punish people,” said Simmons of Revenge’s directness. “I want people to know when they get it, they will be punished.”

This fighting talk seemed to work. Revenge gave Kiss their first Top 10 album in the US since Dynasty back in 1979. But despite its musical qualities, it didn’t have legs. It may have eventually reached gold status, shipping 500,000 copies, but that was a fraction of what the likes of Nirvana and Pearl Jam were selling.

In Kiss’s heads, there was only one solution: if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. While 1993’s serviceable live album, Alive III, kept the fanbase happy, behind the scenes Kiss intended to tear up the blueprint. In 1994, Stanley and Simmons met with Alice In Chains producer Toby Wright.

“They wanted to follow a little hip trend going on at the time called grunge music,” Wright later recalled. “The bottom line was, like all artists, they wanted to sell records.”

Kiss weren’t the only veteran band to abruptly change direction – Mötley Crüe and Def Leppard were having the same thoughts. But Stanley and Simmons embraced it more than most. Dispensing with the party metal anthems and big ballads in favour of a dark, grinding sound that was closer to Soundgarden and Alice In Chains than anything Kiss themselves had written before, new songs such Hate and Master & Slave were as blunt and dirgey as their titles suggested.

“I remember getting into a big argument with Gene about the direction of the album,” said Wright. “He said he wanted to be like that ‘bald guy, the one that’s on the top of the charts.’ He meant Billy Corgan.”

The world would have to wait a while to hear Kiss’s new direction. “We were about done with the record when Gene got the call,” said Wright. “Somebody offered him 100 million to put back on the makeup with all the original members. We all knew right as the words came out of his mouth that we were done.” Carnival Of Souls was shelved. Kiss – or at least Gene and Paul – had other business to attend.

Only Kiss would dream of commandeering an aircraft carrier for a press conference. It was April 16, 1996, and the band had invited journalists aboard the USS Intrepid, docked just off Manhattan. But this was aircraft carrier-sized news – they were there to announced Alive/ Worldwide, the first shows the four original members had played, in costume, since 1979.

Anyone paying attention would have realised a reunion was always on the cards. In August 1995, Ace Frehley and Peter Criss had joined the current Kiss line-up to play a few songs during their MTV Unplugged appearance (released the following year as a live album). Tupac’s announcement at the 1996 Grammys confirmed it.

The first show of the tour was set for the 50,000-capacity Tiger Stadium in Detroit, the band’s home-from-home. “To be honest, we weren’t even sure we would sell out the show,” Gene said in his biography Kiss And Make-Up. “Tickets went on sale one Friday night. At six in the morning on Saturday, Doc [McGhee, manager] called me at home to tell me that he had some good news and some bad news. I asked for the bad news first. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘we don’t have any more tickets to sell.’ We had sold out the whole stadium in under an hour.”

Within four days, 40,000 tickets had been sold for the tour. Any worries that this would be anything other than a success fell away, as did the old issues between the warring members.

“Before the first show I was sitting next to Gene and I started beating out a fill on my leg, and then I started playing his leg, just like I used to do for our big shows twenty years earlier,” wrote Peter Criss in his own biography, From Makeup To Breakup. “I finally broke him. He started laughing. ‘You Italians, nothing changes, huh?’”

The show itself was a triumph. The set focused exclusively on the band’s imperial 70s era, hitting all the buttons Kiss fans wanted to hear: Deuce, Strutter, Firehouse, Rock And Roll All Nite, even Frehley’s solo hit New York Groove.

“The force of the crowd reaction nearly lifted me off my feet,” recalled Frehley. “When the show was over, we congratulated each other backstage. There was a genuine feeling of camaraderie.”

The Alive/Worldwide tour ran for nearly 18 months, raking in over $140 million. If it wasn’t quite the unalloyed triumph Gene Simmons would have liked – a handful of shows towards the end of the tour were cancelled due to low ticket sales – it still succeeded in putting Kiss back on the pedestal where they belonged. The next logical step would be for the original foursome to record a new album together.

Confusingly, there had already been a Kiss record released mid-way through the Alive/ Worldwide tour, though this was the shelved Carnival Of Souls rather than a proper follow-up to Revenge (or, more accurately, 1979’s Dynasty, which was the last Kiss album to feature Stanley, Simmons, Frehley and Criss).

Carnival Of Souls limped apologetically to No.27 in the US, its grunge stylings already old hat. No, the reunited Kiss still had something to prove. They needed to hit the studio and make a record that would properly crown their comeback. And that’s when things really started to go wrong.

In truth, the camaraderie that Ace Frehley talked about after Kiss’s comeback show had worn off by the time they began work on their 18th album. Stanley and Simmons’ initial plans to make an old school rock’n’roll record featuring all four members on every track swiftly fell by the wayside. According to engineer Mike Plotnikoff, the decision to use outside musicians was made by producer Bruce Fairbairn.

“Gene and Paul wanted it to be the original band, [but] when Bruce heard Ace and Peter play in preproduction, he thought to make the kind of record he wanted to make, Ace and Peter wouldn’t cut it as players,” Plotnikoff recalled.

In the end, all four members played together on just one track, the Frehley-sung Into The Void, though they all sang on the self-mythologising You Wanted The Best. For the rest of the album, Criss’s drum parts were played by session man Kevin Valentine.

Ace got a better deal, appearing on four tracks. Ironically, the man who would eventually replace him, Tommy Thayer, handled guitar on the rest of the album, with Bruce Kulick also pitching in on a couple of songs. Unsurprisingly, neither Ace nor Peter were happy with the situation.

“I wasn’t invited to the studio,” said Frehley. “When you hear Paul and Gene talk about it, it’s like I didn’t show up. The reason I’m not on any of the songs is because I wasn’t asked to be on them. I just wasn’t invited to any of the sessions.”

Paul Stanley had a different view of matters. “We tried to do a Kiss album, and it was an ill-fated attempt because there was no real band,” he said. “For a band to make a great album, it has to share a common purpose, and we didn’t have it.”

The resulting album papered over the cracks. Psycho Circus wasn’t the Kiss comeback album fans wanted, but it was far from catastrophic. Songs such as You Wanted The Best, I Pledge Allegiance To The State Of Rock And Roll and the bombastic title track called back to past glories, while the semi-orchestrated Journey Of 1000 Years provided an uncharacteristically brooding closer. The only bum note was We Are One - a treacly we’re-in-init-together anthem that almost drowned in its own irony.

Tensions were kept on a low simmer during the subsequent world tour. Kicking off on Halloween 1998, the spectacular Psycho Circus stage set featured groundbreaking 3D visuals on the video screens, along with several tons of pyros every night.

“We want to bring the fun back to rock’n’roll,” Gene Simmons had proclaimed before the dates kicked off, and it certainly lived up to that promise. But not everything was rosy in the garden. Ticket sales were slower than on the reunion tour, and a proposed second leg in 1999 never happened. Worse, Stanley and Simmons were becoming exasperated with Frehley and Criss.

“We brought those guys back and they were just completely apologetic and remorseful and thankful to be back,” Stanley recalled. “And yet it wasn’t too long after things started to happen again that they started doing the same stuff. And it just became ugly and no fun.”

Drastic action was needed. In 2000, the band announced the Kiss Farewell Tour. Except it wasn’t goodbye to Kiss – just to Ace and Peter.

“The farewell tour was us wanting to put Kiss out of its misery,” said Stanley. “And for a while, honestly, we lost sight that we didn’t have to stop – we had to get rid of them.”

In fairness, Frehley and Criss didn’t help themselves. The guitarist reportedly skipped rehearsals, blaming Lyme Disease. Worse, he failed to turn up on time before a show in California, forcing the band to fit out Tommy Thayer – by then Kiss’s tour manager - in the Spaceman costume, ready to step on stage in his place.

Ace walked into the dressing room about 20 minutes before the show was scheduled to start. He looked at Tommy – fully dressed and made up, with his guitar on, ready to go – and just said, ‘Oh, hey Tommy, how you doin’?’” says Stanley.

Criss was little better according to the singer. Following one show, Stanley was cornered by Doc McGhee who angrily told him the drummer was playing too slowly.

“This will not do,” said McGhee. ‘These guys are just terrible. You have to make changes.”

For his part, Peter Criss was feeling just as frustrated. Breaking point for him came during a show in North Charleston, South Carolina. At the end of the set, Criss trashed his kit, sending a huge tom-tom drum rolling towards an unsuspecting Stanley. He quit the tour – and the band – that night, leaving his predecessor, Eric Singer, to finish the dates in his place.

Criss would return again for another tour in 2002, but departed for the third and final time in 2004. Unlike his colleague, Frehley made it to the end of the Farewell tour, but that was it for him too. He’d reached the end of the road with Kiss.

“They wanted to tour constantly and record constantly, over-merchandise the brand, and that made me crazy. I’m not a kid anymore,” the guitarist later said. “Touring constantly can be very exhausting. I don’t want to put myself in that position.”

Paul Stanley had a different take on it. “I was angry at Peter and Ace for being disrespectful toward everything we had accomplished and everything the fans were giving us,” he said. “It was unbearable.”

In that war, there were only ever going to be two winners: Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons. Criss and Frehley were once again cut free from Kiss, and Thayer and Singer took their positions - and, more controversially, their make-up. Not that Paul and Gene cared what others thought. Sentiment was never an issue – not when the future of Kiss was at stake.