What’s your favourite opening track on a double live album?”

Whenever I’m asked that question, and it’s akin to a chat-up line in the waters in which I paddle, my answer is unswerving: “Detroit Rock City, from Kiss Alive II.”

Why? The roar of the crowd, the smell of the pyro, plus of course the sheer grandeur of a song that has never been dropped from the Kiss live set. Ever. Only right and proper then that this Paul Stanley-penned paean to the Motor City (“The first town that opened its arms and legs to us!”) should have come into the world as track one, side one of the New York group’s most cherished studio outing.

Released in 1976, Destroyer is of course the work in question, and for Paul, Gene Simmons, Peter Criss and Ace Frehley the pressure was well and truly on. Achieving success is one thing, following it up another, and this time around the New Yorkers were following up a corker: Kiss Alive!, the first in a venerable series. Kiss Alive! had gone off like the proverbial greased rodent, rebranding the four as a runaway success.

“You know how McDonald’s have a sign that ticks over every time they sell another burger? Well, Kiss Alive! was like that for us,” enthuses Paul, casting his mind back. “We went from 70,000 sales to a million sales, and it just kept going.”

For America’s most flamboyant sons, Kiss Alive! was a genuine education, proving in gold and platinum currency that the appeal of the band was based on more than just music. Which is not to devalue the studio recordings 1974-75, as some of the most popular Kiss songs ever were put to tape in that period (including US chart hit Rock & Roll All Nite).

Think of it like this: if Kiss (1974), Hotter Than Hell (1974) and Dressed To Kill (1975) were the foreplay, the whisper in the ear and the hand on the thigh, then Kiss Alive! was the moment when the passion finally peaked – it was all there, the heavin’ and the humpin’, the solos and the raps, the whole nine yards (and that’s just Gene’s tongue).

“Well, Kiss Alive! was what we stood for,” says Paul matter-of-factly, “the embodiment and the magnification of everything we were as a band. It was Kiss on steroids.”

But if Kiss Alive! was going to be a springboard rather than an anchor, then Kiss couldn’t afford to rest on their platforms – they needed to return to the studio (the Record Plant in New York) with more than just a glorified engineer, however good the songs at their disposal.

What they needed was a cheerleader and a guru. A hard man with a plan. Someone who would leave no shape unthrown in the quest for musical greatness. Enter producer Bob Ezrin.

“I’d first crossed paths with Bob up in Canada where I was doing some promotion,” recounts Paul. “He asked me if I liked the sound of my own records, and because I was young and full of – what’s the expression? – piss and vinegar, I said that I did.

“However, I was well aware of what he could do in the studio, of the work he’d done with Alice Cooper [Ezrin first joined forces with AC for the 1971 album Love It To Death], which was cinematic and atmospheric, yet still totally rock’n’roll; his fingerprints are all over that stuff, so it was just a no-brainer that he should be our one and only choice for Destroyer.”

In making their first three albums, Kiss had simply written the songs then gone into the studio to record them, before heading out on tour. It was a straightforward process, the way presumably every record was made. Well, not exactly. In the world of Bob Ezrin (dubbed ‘Bobo Earzone’ by Hanoi Rocks; he worked with them on their Three Steps From The Move release in 1984), there was a little thing called ‘pre-production’ that had to be factored in – a first-time experience for Kiss, who must have felt they were suddenly back at school.

“Actually, brutal boot camp was more like it,” winces Paul. “Bob definitely had a whistle round his neck. At the time, of course, we were basking in the glory of our success with Kiss Alive!, and we weren’t exactly open to outside opinion. But we listened to him because he was, well, right! With Bob, it was ‘teach us’.”

Three years later, Ezrin would be in the studio with David Gilmour, Roger Waters et al helming the Pink Floyd classic The Wall, so the Kiss camp can at least reflect with pride that they put their faith in a good ’un. And it couldn’t have been easy. Not only did the Toronto-born taskmaster insist that they tune their own instruments (which is a bit like asking the boy Beckham to wash his own kit), but he arranged them in a circle, Alcoholics Anonymous-meeting style, going through the material with an attention to detail usually reserved for the building of monuments out of matches.

“Sometimes he’d ask for most of the band to leave the rehearsal space so he could focus in on a particular person,” says Paul. “He might want to run through the drumbeat to Detroit Rock City with Peter, or maybe talk to Gene about the bass part, which incidentally is based on Curtis Mayfield’s Freddie’s Dead [from the 1972 soundtrack to the Superfly movie; check it out, it’s true].

“The rehearsals were long, but they were exciting, and it wasn’t just the music he was pushing us on, it was the lyrics too – the ‘fuck me, suck me’ songs were out.”

“The rehearsals were long, but they were exciting, and it wasn’t just the music he was pushing us on, it was the lyrics too – the ‘fuck me, suck me’ songs were out.”

While most of the material was pieced together in the ‘magic circle’ manner outlined above, with choruses, verses and bridges run up the flagpole in the hope of an Ezrin salute, a couple of songs – Stanley compositions both – were already in the can… almost. One of these was God Of Thunder, to all intents and purposes complete, and the other was Detroit Rock City, pretty solid in the chorus, but still seeking a theme.

The turning point came when Paul remembered a show in North Carolina where, tragically, a fan had been killed by a car outside the venue. Straight away, Ezrin saw that here was the meat of the song, and – with metaphorical pompoms waving like mad – he set about encouraging the frontman to complete the lyric, the end result being the story of a kid who hears about his own demise (and, no, despite what you may have read on the internet, Gene doesn’t take the part of the radio reporter at the start).

Given the band’s special relationship with Detroit, it was only natural for that city to be spotlighted in the title, but in many ways the song is about any place, every place, that likes to pick up a paint brush and shake loose its mane.

“That venue we played in the UK, Bingley Hall in Stafford…” Paul’s voice trails off wistfully, reflecting on Kiss’s legendary appearance there in September 1980. It was Friday, it was the fifth day of the month, and the event is still spoken of in hushed tones by those lucky enough to have borne witness. “That place was most definitely Detroit Rock City…”

God Of Thunder, meanwhile, was to prove a double-edged sword for the man known as the Starchild; a great song no doubt, and pats on the back weren’t slow in coming, but a great song he’d written for himself.

“When Bob said that Gene should take the lead vocal, I just couldn’t believe it.” Paul still sounds surprised. “That’s the thing about working with a real producer; he can keep the band focussed by assuming control, and that’s generally a good thing… apart from when he disagrees with me. Of course, it was absolutely the right call, but it was hard for me to appreciate the logic at the time. I was speechless.”

And it wasn’t just Gene who made his presence felt on the song – the Ezrin offspring (young sons David and Josh) were given a ‘big moment’ too, providing the eerie-sounding vocals that really stoke up the atmosphere. “They were wearing little space helmets with walkie-talkies built into them, and they were saying, ‘I’m King Kong, I’m King Kong…’ That’s what you hear on the track.”

God Of Thunder, of course, was destined to achieve great things, swiftly becoming a signature tune for Gene, a man for whom breathing fire and spitting blood were already a way of life.

That was the thing with Destroyer – it was a concept album, sure, but only in the sense that the concept was Kiss itself. The nine tracks (plus outro passage) allowed the band members to further bond with the fans by both exploring and expounding their individual personas, wearing them with the flamboyance of a Liberace fur.

“Kiss Alive! had all the muscle and the spit,” explains Paul, “but Bob replaced that with a cinematic feel. It was a night-and-day difference to what we’d done before, an altogether larger picture of who we were.”

And what they were was indeed something special: Gene, the Demon, a man with a bedpost notched into sawdust; Paul, the Lover, like Casanova on a Viagra and oyster diet; Ace, the (Urban) Spaceman, the perfect companion for some inter-planetary carousing; and Peter, the Cat, a do-or-die dealer in advanced drum dramatics (or something like that).

Ezrin realised that turning these rock‘n’roll heroes into rock‘n’ roll superheroes was the key to giving Kiss their biggest record to date; hence his insistence that Gene grab the mic for God Of Thunder – a piece of self-trumpeting that makes Louis Armstrong look like an asthmatic with a kazoo, and musical vehicles were duly constructed for other members too.

In Paul’s case, it was Do You Love Me?, a song co-written with the legendary Kim Fowley, and for Peter it was Beth, a grandiose orchestral outing that has been described by experts in the field of soft-rock as the ‘proto-power ballad’ (God help us). Two songs that, frankly, couldn’t be further apart – the no-guitars-and-drums tissue-fest that is Beth and the ‘living large’ anthem that is Do You Love Me?, a song later covered by both Nirvana and Girl.

“It’s a song that deals with the age-old question: do you like me for who I am or for what I have?” reflects Paul. “But to be honest, I really didn’t give a rat’s ass. Back then, our lives were all about instant gratification – commitment didn’t really come into it. We were enjoying our success, and when it came to women, our motto was pretty simple… motive irrelevant, looks important.”

With Ezrin bringing the quality hammer down hard, there was little danger of ‘filler’ creeping in below the radar, although the song that hovered closest to the ‘f’ word, or so it seemed, was the aforementioned Beth – penned by Peter Criss and former Chelsea bandmate Stan Penridge, and given a serious sprinkling of fairy dust by the producer.

This emotionally-charged exercise in cotton-wool crooning has roots stretching back to the early 1970s, when it revelled in the title of Beck – basically, a number inspired by Chelsea guitarist Mike Brand’s main squeeze, who was forever on the phone while the band were in rehearsal. (Peter, for the record, was married to Lydia, who one presumes wasn’t quite so receiver-happy.) Obviously, the title was tweaked down the line – not to avoid confusion with Jeff Beck, but also to, well, just avoid confusion…

“What’s a Beck?!” shrugs Paul. “It just wasn’t a name that people could relate to.” Originally the B-side of Detroit Rock City, the third single from the album, it wasn’t long before Beth was making a major impact on US radio, with DJs flipping the seven-inch with almost undignified haste (the track was soon given official A-side status).

This sleeping beauty had been well and truly roused, charting at No. 7 Stateside (and turning gold in the process), picking up a People’s Choice Award and dictating that Kiss’s fire and brimstone stage show would, for the foreseeable future, be tempered by the giving out of roses and the wafting of orchestral music through the PA.

Ideally, both the Destroyer album and the Kiss live experience (circa ’76) would also have seen the fast-livin’ Frehley doing vocals on a track, something the other members had been encouraging him to do since he turned up years earlier with the best part of Cold Gin in his pocket. Not wanting to fully embrace the limelight at this point, Ace chose to pass the bottle, er, baton on to Gene (who’d never actually tasted gin, cold or otherwise), and it wasn’t until the Love Gun album (1977) that a bona fide all-singin’/all dancin’ Ace song arrived on the scene.

Paul: “And the funny thing with Shock Me [the track in question] was that Ace did all of the vocals lying flat on his back in the studio. He wasn’t drunk, he just liked the extra pressure on his chest…”

Of course, the horizontal position was one that the Space Ace wasn’t entirely unfamiliar with. Here was someone who had quaffed deeply from the great rock’n’roll goblet; a musician with (platform’d) feet of clay whose unpredictable behaviour – accepted by Kiss Army fans worldwide – was doubtless viewed through different, less rosy glasses by Ezrin. There were rules in place now, remember, requiring a note from an adult to explain absence from the studio, and woe betide anyone caught chewing gum in class.

“Looking back,” reflects Stanley, “this was the start of a new and necessary mindset for us. Basically, if someone doesn’t turn up, the show must go on. You know, Ace has got his life under control these days, I have great fun talking with him, but things were different back then. It’s all been written about already, but he was succumbing to the excesses of the rock‘n’roll lifestyle rather than taking advantage of its perks.”

As a result, Detroit sessioneer Dick Wagner was ushered in by Ezrin to provide guitar – electric and acoustic – when Ace was, to all intents and purposes, lost in space. Apart from the guys themselves, Wagner was the only other musician to pick up a band instrument, most notably for the solo in Sweet Pain, and he made no attempt to disguise his presence by fretting in Frehley fashion.

Simply, he was on board to do the best job he could (having previously played with Alice Cooper, Lou Reed and Aerosmith, credited and uncredited), guided by a producer determined to use every trick in the book to wring out the magic.

These days, it’s quite normal for drummers to lay down their parts using a ‘click track’ – a digital means of keeping to the beat. But back in ’76, this kind of technology just didn’t exist, which is why Ezrin opted for… a cigar box. Actually, a cigar box with a microphone inside, which he would tap with a drumstick to keep the musicians as much in line as possible.

It was this kind of Swiss precision – rock’n’Rolex? – married to an ambition for the project on the larger side of Godzilla, that was the hallmark of Destroyer. With the band having promoted the original Sir Bob to a ‘final say’ position, he was effectively free to don the Napoleonic war bonnet and execute his vision with the zeal of a man whose next job was conquering Europe. There would be no holding back now – no idea too grand to try or too OTT to execute.

Forget mere kitchen-sink production, what we had here was closer to a rocket-firing washing machine, with all manner of extra-curricular elements boldly set on ‘spin’: choir, orchestra, car crash, calliope (a big organ if double entendres are your thing), there was plenty to catch the ear and spark the imagination, with pianos and power chords working closely together and all sound FX printed directly onto tape. A less self-assured producer would have recorded everything au naturel then added the required delay, distortion, etc. in the mix, but not so Ezrin, who preferred to add the icing while the cake was being baked.

“So if you were to put the multi-track of Destroyer back up through the desk, it would sound just like the album,” confirms Paul. “Everything would already be there.”

For this writer, it all comes together to greatest effect on Detroit Rock City – which is in no way to skirt over the charms of Shout It Out Loud (put together in the living room of Ezrin’s New York apartment), Flaming Youth (a title inspired by a New York band from the early 70s), King Of The Night Time World (co-written with Hollywood Stars member Mark Anthony, among others) and the rest.

It’s a prime selection, no doubt, but I’m magic-marking Detroit Rock City because it provides (to get technical for a moment) a double squeeze of the lemon – not only one of the finest songs to flow from the Paul Stanley pen’n’plectrum set, but a song with a magnificent solo section that suddenly takes the whole thing to a higher level of enjoyment. Let’s face it, Thin Lizzy’s Emerald aside, there aren’t too many hard rock songs that give the listener the chance to hum along with the solo as much as the chorus… well, this one does.

“And Bob sang that solo section note for note, then asked Ace to learn it, including the harmony,” explains Paul, happy to give credit where it’s due. “The drumbeat, the bassline, it was really all Bob.”

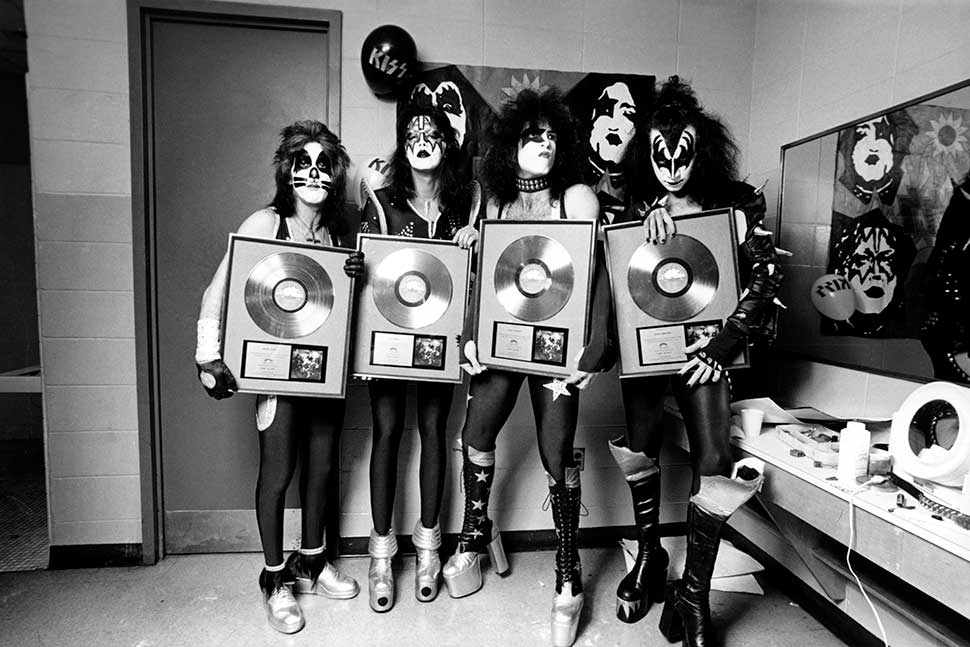

In keeping with the mighty sweep of the music, Destroyer saw the band going for broke on the visual side too. Out went the old costumes (presumably not to the local Oxfam shop), and in came a suitably all-conquering new look – a look officially unveiled during a press day at the Record Plant where band and producer were recording the Harlem Boys’ Choir for Great Expectations. In came the eager media, in came Ezrin (wearing top hat ’n’ tails) and in came Gene, Paul, Peter and Ace sporting a style that I’m now going to take a deep breath and describe as ‘post-apocalyptic-comic-book-chic’.

It was this look (‘PACBC’ for short) that painter/illustrator Ken Kelly was asked to capture for the sleeve of Destroyer, and the result was perhaps the most famous representation of the band ever – a magnificent piece of rubble-rousin’ art, sometimes copied, sometimes spoofed (as on the Sloppy Seconds album Destroyed), but forever loved.

The only trouble was, the first painting by Kelly – a relative, incidentally, of the equally celebrated Frank Frazetta – showed the four in the wrong costumes, so changes had to be made, and made quickly. With Destroyer having done so much to define what Kiss became at the back end of the 70s, a decade that saw the band moving from rehearsal room hopefuls to multi-platinum gods, it’s interesting to speculate whether their growth would have been the same were it not for the complete merging of image, music and message that takes place on this album.

Yes, the band would hook up with Ezrin again – on 1981’s (Music From) The Elder (a low point) and 1992’s Revenge (a return to form) – but the mojo would never work harder than it did right here, right now.

The fact remains that time has been kind to Destroyer, a record still very much connected to its own hair and teeth. Even the last track – a sonic montage usually referred to as Rock & Roll Party – has come to sound like a relevant part of the album, when in fact it was put there purely and simply to soak up some time (Destroyer is under 35 minutes long).

What this means, in short, is that the editors of Rolling Stone magazine, who recently voted this triple platinum US success the 496th Greatest Album Of All Time, should have their collective ears syringed with Cillit Bang; Destroyer is much, much better than that – recorded in two separate sessions and showing what can be achieved when the studio gods are grinning away like fools.

“I guess ‘swagger’ is probably the right word,” concludes Paul. “The songs have a truly majestic feel, without coming across as either pompous or contrived, and Bob was just a joy to work with – the first genuine producer we’d put our trust in.

“I know that he didn’t really like the title, he thought Destroyer sounded negative, but for me it was too good not to use. This was one of those records where – from the music right through to the name – the planets were all in perfect alignment.”

Cue massed humming of the Detroit Rock City guitar solo.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 93, in April 2006. The 45th Anniversary edition of Destroyer is out now.