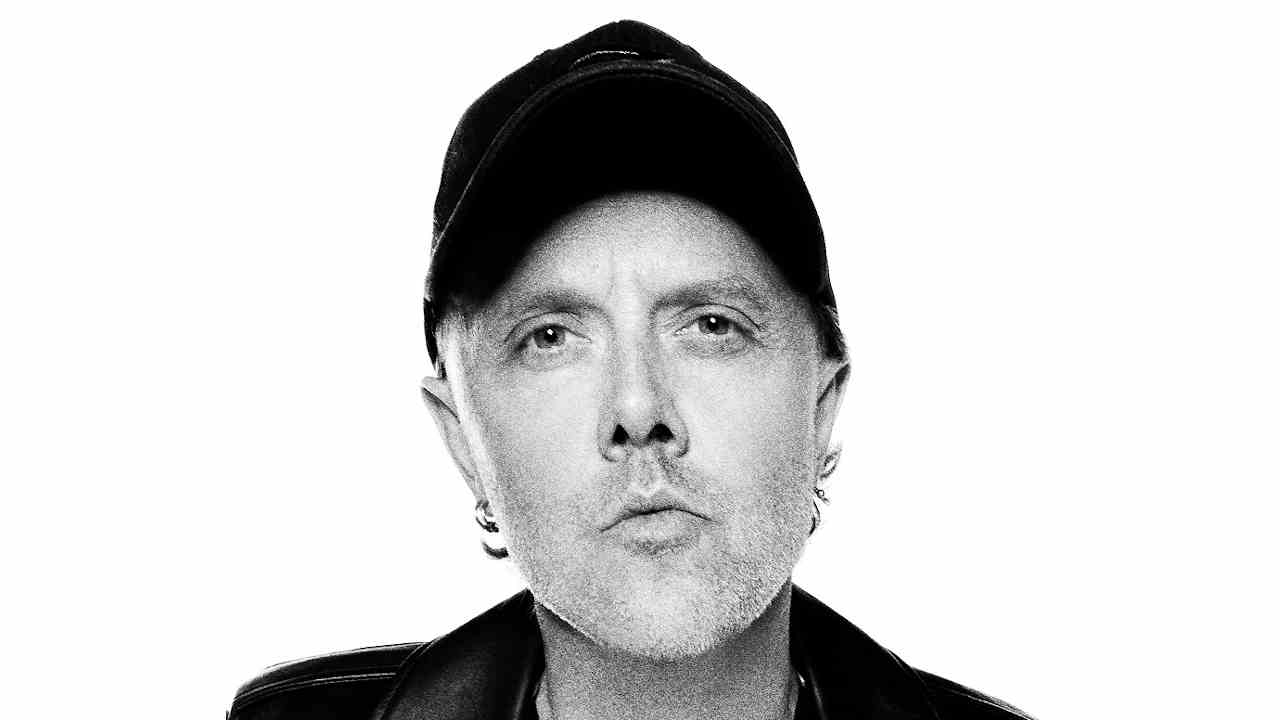

Lars Ulrich: “There’s not a f**king moment I’d change”

Lars Ulrich is more than just Metallica’s drummer – he’s the beating heart of the band. In this classic 2012 interview, he looks back over the band’s epic journey

The world’s biggest Metallica fan has spent the last 40 minutes talking pretty much non-stop about his favourite band. This a man who lives and breathes his chosen subject, to the point where he could draft a PhD paper on them with his eyes closed. Pull out a live date and he can tell you exactly where he was; dust down the most obscure album track in their back catalogue and he can tell you what he was doing when he first heard it. But don’t presume that this is blind love: he’s as aware of their missteps as he is their triumphs; he’s their harshest critic as well as their biggest champion. But then he’s allowed to be. The world’s biggest Metallica fan also happens to be their drummer.

“Yeah, I don’t think that’s unfair to say,” says Lars Ulrich in an accent that still sits halfway between Copenhagen and California. “When you’re on the inside, you get a certain… perspective.”

Lars occupies a unique position in the band he co-founded in Los Angeles in 1982. He’s both their biggest cheerleader and their chief whipping boy. His tireless hustling during the band’s early years ensured they didn’t slip down the back of the sofa with the likes of Laaz Rockit and Jag Panzer, while his single-minded devotion to the cause helped propel them from cult thrashers to A-list stars. Metallica wouldn’t be Metallica without James Hetfield. But they certainly wouldn’t be the biggest metal band ever without Lars Ulrich.

The flipside is that, to many, Lars is Metallica. Not onstage – that honour goes to the larger-than-life James. But the drummer’s garrulous presence in the press has turned him into Metallica’s public figurehead. All well and good when things are going well, but not so good when things aren’t. Like the CEO of some huge conglomerate, when Metallica’s fortunes have hit a sticky patch, Lars Ulrich has borne the brunt of it. And there have been a few sticky patches over the last 30 years.

“It’s been eventful,” he says with ironic understatement of the band’s journey. “I know some people are sick to death of hearing it, but we have a newfound appreciation for our success and how fortunate we are that we can still function 30 years later.”

- On a budget? Here are the best budget turntables

- Best headphones 2020: supercharge your music listening

- Spotify vs Apple Music vs Tidal: which streaming service is best for rock and metal?

There’s a battered old sofa in Metallica HQ, their studio-come-clubhouse across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, that has played a small but significant part in their career. It’s the sofa that Lars sat on when he and his bandmates reconvened in the mid-noughties after a year apart to talk about their turbulent recent past and their immediate future – specifically whether they had one or not. It’s the same sofa that Lars is sitting on right now, as he takes a break from Metallica’s day-to-day business to talk about virtually the same subjects, more than half a decade on.

The early part of the century was a strange one for Metallica. For the first 20 years of their existence, they were about as bulletproof as it gets. Then, sometime around the drummer’s much-publicised run-in with Napster in 1999, things took a turn for the wobbly. The ensuing half-decade is well documented – James’s near-breakdown, the departure of Jason Newsted, the painful creation of St Anger and the baffled reaction that greeted it, all captured with cathartic honesty in Some Kind Of Monster – was the closest Metallica have ever come to extinction. All of a sudden, this most super-human of metal bands suddenly seemed all too human.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The turning point came in November 2005, a couple of weeks before they were due to return to the fray with a pair of shows supporting the Rolling Stones in San Francisco. They’d gathered around that sofa to draw up a road-map for they way forward.

“The few years after the near-meltdown of the band that was so well captured in Some Kind Of Monster were obviously not easy,” says Lars. “We were still trying to figure it out, post-Hetfield rehab, post-Jason leaving, post all that stuff. But in November 2005, we walked into HQ and sat on the couch that I’m sitting on now, and everything felt really fresh. There was no film crew, no psychiatrists, everybody was rested. I think, especially, Hetfield felt like whatever it was he’d been struggling with in the wake of his issues, and readjusting to touring and the whole world of Metallica, it felt like all that had dissipated.”

- Kill ’Em All: the story behind the debut album

- “Whose f**king idea was this?”: how Metallica’s made the spectacular S&M2

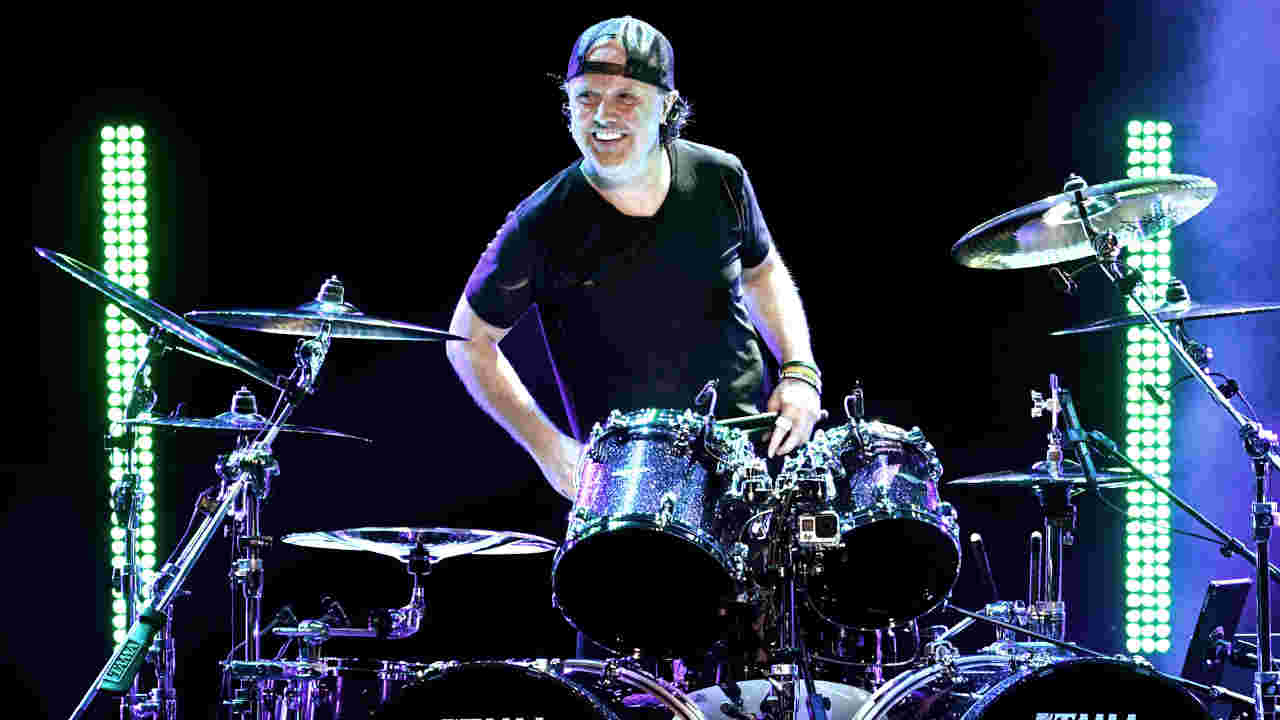

James might be the one at the microphone, but he’s not Metallica’s only frontman. Behind him, Lars spends much of the band’s shows wrenching the spotlight away from his bandmate – he provides the gurning, mugging, drumstick-pointing foil to James’s monolithic presence.

“Look, I’ve heard it – ‘Why does he get off the kit all the time, why is he jumping around?’” he says. “That’s what I do. It’s what I’ve always done. I’ve always wanted to connect with the audience. Not as a kind of show-off: ‘Look how big my dick is.’ But ever since the beginning of Metallica, we’ve tried to get as close to the audience as possible. And that meant all of us, not just the singer. It’s just been part of our live shtick, and works for us because it keeps us firing on as many cylinders as possible. When I get up onstage, man, I turn into a caricature. I see it myself – the silly faces, the tongue hanging out, all that stuff – but it’s not really something I can do much about. It just happens when I get up there. It’s not something you can turn on and off.”

During their first decade, Metallica went from thrash metal princelings to kings of all they surveyed in double quick time, and they’ve stayed there ever since. But even kings get bored and feel the need to shake themselves up once in a while. With Metallica, that desire has manifested itself in some peculiar decisions. Sometimes, it’s been part of their natural evolution, whether stylistic diversions of Load and Reload, two albums that don’t deserve the scorn heaped on them, or something completely left field like Lulu, which made the reaction to Load look tame. Sometimes it’s felt like a test – of their fans as well as themselves.

More than once today, Lars describes Metallica as “a metal band, quote-end quote”, suggesting an underlying frustration that they’re still ghetto-ised after all these years.

It’s the sort of thing guaranteed to rile the portion of their fanbase that objects to the idea of 48-year-old men having diverse tastes in music or the ones who overlook the fact that Metallica have done more for their chosen genre than most other bands.

Still, the question has to be asked: if he was filling in an online dating form, would he put ‘Metal Fan’ as part of the description?

Ha ha ha ha! “Of course I would! Fuck yeah! God help my poor assistant Barbara, but about six months ago I asked her to put all the CDs in my library onto a couple of iPods, and I’ve got them in my car. I listen to stuff all the time. Do you remember Loudmouth? Great American band from the late 90s. I discovered them on my iPod a week ago. I was listening to [venerable Japanese metal band] Bow Wow a couple of days ago.”

What about modern metal?

“I got the new Soundgarden record yesterday. I’m looking forward to listening to that in the next couple of days. I just got the new Sword album, which is fucking fantastic.

"Obviously, when you carry 250 gigabytes of music around with you, you spend a bigger portion of time listening to older stuff than you did 10 or 20 years ago. Back then you mostly carried the latest releases around with you.”

- Metallica’s Ride The Lightning: the album that broke the boundaries of thrash

- Every Metallica album ranked from worst to best

Metallica marked the end of their first three decades with the mother of all parties: a week-long series of gigs at The Fillmore in their hometown of San Francisco, which featured guest appearances from former members, past collaborators and assorted musicians who have influenced them over the years. If anything refilled the tank of goodwill for Metallica, it was those gigs.

Even so, the idea of one band sustaining a 30-year-career – and a massively successful one at that – must have prompted some existential internal dialogue. Did he ever wake up and think, ‘How the hell did that happen’? What follows is a typical Lars Ulrich answer: long and convoluted and running parallel to the point, if not quite shooting off at right angles. The short answer is ‘no’. This is the long answer:

“There are times, because I have two lives… I could be up at 6.45, being Mr Dad. Making breakfast, taking kids to school with hundreds of other parents. That’s the kind of domestic thing that a lot of rockers deal with, obviously. Then a couple of hours later, you’re driving to the airport to jump on a plane to Kansas City, where you’re playing a gig in front of 19,000 people. Sometimes you sit there and go, ‘Huh, this is really weird – a few hours ago, I was taking my kids to school. These two worlds co-exist, and that’s kind of a mindfuck. Mindfuck is a word that shows up on my radar a lot. The whole thing is kind of a mindfuck. But the fact that it’s been four decades? It’s not something that I carry with me a lot.”

You formed Metallica when you were 18. You’re 48 now. Do you ever feel old?

“I don’t feel particularly old,” he says. “And I don’t feel particularly weathered, other than sometimes when we’ve played a couple of shows, and I’ve not warmed up in the proper way. Generally, knock on a lot of wood, we’re in pretty good shape mentally and physically. It’s not like we’re walking around like these old fucking dinosaurs.”

There have been changes in the last 10 years, of course. To combat the 10.5 magnitude earthquake of the St Anger period, Team Metallica put in place a set of rules to ensure the whole edifice wouldn’t come crashing to the ground in future. Partly, these were to pre-empt any potential personnel crises; partly they were down to the simple needs of four family men in their late 40s who have spent the past three decades circling the globe with barely enough time wipe their hairy arses.

- Master Of Puppets: how Metallica made the greatest metal album of all time

- Metallica Mondays: Your ultimate guide to every show

“We have a rule in our band where we don’t stay away from home for more than two weeks. We tour in very, very short spurts: a week on, a week off, or two weeks on, two weeks off if we’re doing Europe or Australia. It stops us from falling off the deep end. It’s certainly not the most economical way of touring, but we feel like it’s an investment in our own sanity.”

Is there a part of you that misses the chaos and carnage of the late 80s and early 90s?

“Ha ha ha! ‘Carnage’ – that’s a brilliant word! Some of the shit we got up to, especially because we were a little more under the radar than some of our peers, was carnage. There is not a fucking moment of that I would change. I’m not one of those regretful people. I’m glad I lived it. I’ll always access it in the back of my mind. I’ll be able to pull up stories – I’ll have a little smile on my face as I relive what happened in Portland, Oregon, in 1992 or wherever.

“I’m sitting here doing this interview, then in about 13 minutes I have to go pick up my kids to take them to a swimming lesson, so it’s very different structure to back in the day, obviously. Once in a while, you do kind of wish you could drive to the airport and fly to Vegas and sit yourself in front of a blackjack table for a whole day. It only lasts for a few seconds and I wouldn’t change anything about what I’m doing today, but I’m really, really happy that I have all that carnage in my head.”

Do you ever think there’ll be a day when you wake up and go, ‘You know what? I’m bored of being in Metallica’?

“I don’t think that I’ll ever be bored of being in Metallica. I think that one of two things can happen. One, is the physicality of what we do – if we don’t have the strength to do it physically any more. We will always have the strength to do it mentally, so I’m not worried about that. But if there ever comes a time when we feel that it’s not going on all 12 cylinders, then I hope that we have the guts to walk away from it.

“The other thing that could happen is that you decide you want to pursue something else: ‘I’m really interested in film’ or ‘I’m really interested in painting.’ Is there a chance that when I’m 55, I’ll want to write a movie? Or that James Hetfield will want to make a country record? Or that Kirk Hammett will want to go surfing for a year?

“But I don’t think I’ll ever wake up and go, ‘I’m bored of being in Metallica’, because of the nature of who we are as people, and the dynamics in our personalities. We always make it interesting for ourselves. That’s why we do crazy shit like Some Kind Of Monster and the 3D movies. We throw ourselves these challenges. It’s to make sure that boredom never sets in.”

That’ll be a ‘no’, then.

It’s usually hard to feel sorry for a multi- millionaire rock star, but sometimes that’s exactly the reaction Lars provokes. Love him or loathe him, 30 years haven’t dimmed his enthusiasm for music in general and Metallica in particular. That’s more than you can say for an awful lot of people who have been doing the same job for the same length of time, whether they’re musicians or binmen. For all his perceived faults – the cockiness, the arrogance, the gurning – he’s neither lazy nor naïve nor out-of-touch with what people say about him and his band.

“Listen, we’re a gang of guys that stand up for each other and stand up for what we do,” he says. “Within that gang are four people who are pretty diverse and, between us, cast a fairly big net in terms of what we’re into. But we’re very proud of where we come from and we’re fiercely protective of what we do.”

Thirty years on, do you ever think about the younger version of yourself? Looking back, do you think the 18-year-old Lars was a go-getting kid or an unbearable prick?

“I’d say that if the word ‘prick’ has been applicable, it would be more late 20s, early 30s. That’s when it got a little nutty there, post-Black Album success. I think, thankfully, we’ve left that behind. But the 18-year-old me? I would say that he was pretty green and pretty starry-eyed. He was still a virgin at 18 and still had a lot of living to do. He was just a little nerdy loner who loved his metal. He wasn’t a misfit or anything, he was just a loner. I loved being by myself. That’s what me and Hetfield found in each other. We lived in our own world, and we bonded over all things metal.”

What about vice versa? What do you think the 18-year-old Lars Ulrich would think of the 48-year-old version of himself?

There’s a few seconds’ pause, which is lifetime in Lars Ulrich’s terms. “I think he’d think that he’s alright. He does a pretty good job of keeping it real and dealing with all the things he does. I realised that I say one phrase quite often: ‘I’m doing the best I can.’” He laughs. “And I think the 18-year-old would look at the 48-year-old and go, ‘He’s doing the best he can.’”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.