You can make a case that Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs is Eric Clapton’s greatest post-Cream achievement. A double-album of musical grit and emotional tenderness featuring the heavenly glissando of guitarist Duane Allman, it reshaped blues rock into a new soft-rock genre. And the title track is about as iconic as a song can get.

The album was inducted into the Grammy Hall Of Fame in 2000 and it figures in just about any ‘Greatest Albums Of All-Time’ chart you care to name. But it was an almighty flop at the time of its release in 1970, when it made a brief, mediocre showing at No.16 in the US chart and failed to chart at all in the UK. The reviews were not great either, with Melody Maker complaining of “pretty atrocious vocal work” and songs that induced “complete boredom”.

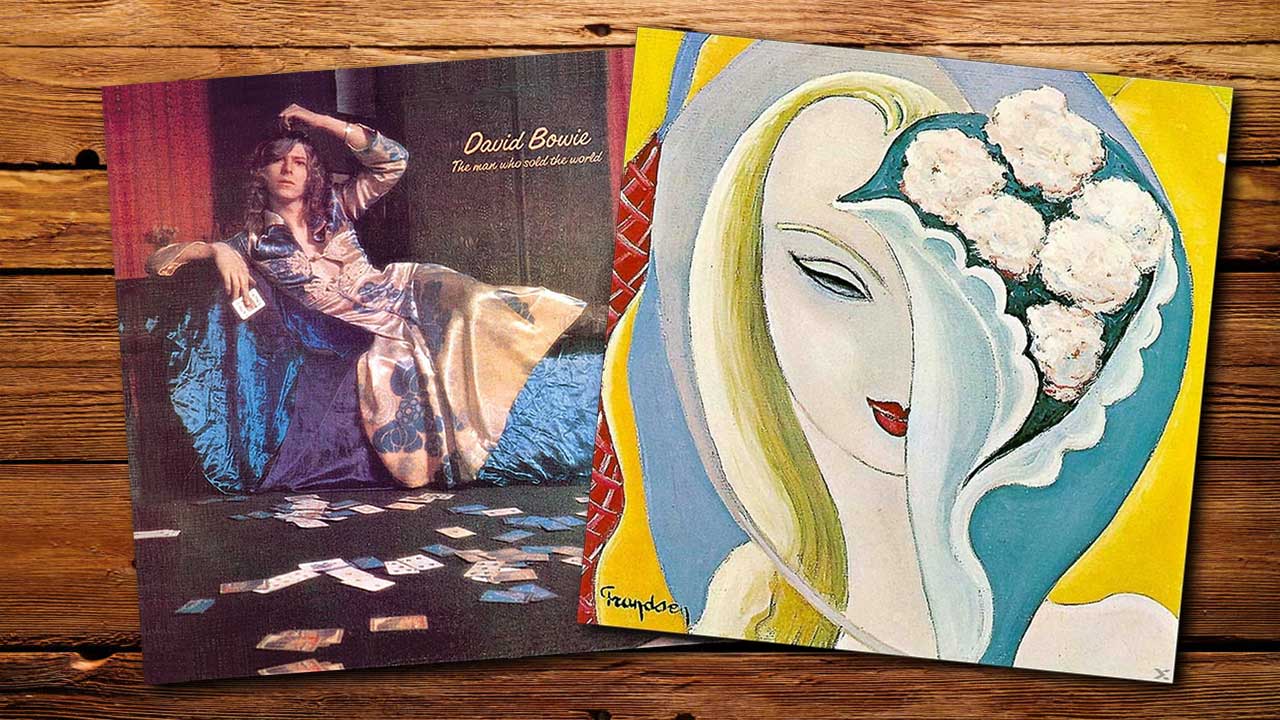

David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold The World is likewise an album that stands close to the summit of the starman’s achievements. A work of bleak, gothic, otherworldliness, featuring guitarist Mick Ronson and the prototype Spiders From Mars band, it found Bowie at an early heavy-rock peak with The Width Of A Circle and She Shook Me Cold, and boasts another iconic title track, elevated by the famous version by Nirvana, among others.

Rolling Stone called Bowie’s album “uniformly excellent”, and it has since been lionised as his “first great album” (it was actually his second album). Yet when it was released in 1970 in the US (1971 in UK), it stiffed. No chart action whatsoever.

It was only two years later, after the success of the Ziggy Stardust album, that The Man Who Sold The World finally entered the charts and began its long, gradual ascent to hallowed status.

Other albums released around the same time suffered a similar fate. In America, ZZ Top’s First Album and the self-titled debut by The Allman Brothers Band were both commercial non-starters. The subsequent success and longevity of the Texan trio has prompted a predictable reappraisal of their fledgling effort, while the Allmans’ album has long been viewed as an outright classic, with songs including Trouble No More, Dreams and Whipping Post among the most evergreen in that long-running band’s repertoire.

So what was going on at the turn of the 1970s? Were audiences and critics really so cloth-eared? How could these all-time great albums have been ignored at the first time of asking? What has happened since then to change our minds?

Of course, we look back on the past, in this case on certain albums, through a telescope that zooms in with a clarity provided by hindsight, while ignoring the bigger picture of the times in which they were framed.

1970 was a strange, in-betweener year. The 1960s and psychedelia were over and The Beatles were on their last legs. T.Rex and the glam revolution were just around the corner (Ride A White Swan came out in October 1970 but didn’t peak in the chart until the following year). Rock was in a good place. Led Zeppelin were rampant, topping the album charts in both the UK and US twice (with II and III); Free were, for sure, All Right Now; and Deep Purple’s In Rock had finally given Ritchie Blackmore’s boys a substantial hit after three previous albums that had all failed to chart.

As one of the pioneers of the genre, Clapton should have been sitting pretty. Instead he had made himself unmarketable. Battered by the split-up of Blind Faith the year before – a ‘supergroup’ that had been undone, as Clapton saw it, by hype and hubris – he had insisted from the outset that this new band should be billed as anonymously as possible.

Hence Derek & The Dominos, with Clapton’s name strictly kept out of all sleeve artwork and promotional materials. So successful was the ruse that, for a time, people simply didn’t know that Layla was by Clapton.

Not only had Clapton embraced a new, more mellifluous style of performance, he’d also actively renounced his guitar-god status, begun with John Mayall and redoubled with Cream.

“By the time we went to America, we’d play half-hour solos in the middle of anything,” Clapton recalled. “We’d do it in any song. We got into a lot of self-indulgence and a lot of easily-pleased people went along with that.”

Be that as it may, when Polydor Records released Live Cream – a collection of old performances recorded in San Francisco in 1968 – in April 1970 it gained considerably more traction than Layla could manage. Live Cream reached No.4 in the UK, and is now regarded as a classic display of the band at an early peak of their powers, playing extended, take-no-hostages versions of songs from their first album, Fresh Cream, including N.S.U., Sleepy Time Time and Rollin’ And Tumblin’.

The intensity and sheer bravado of the playing is insane, making the album an early marker in a hard-core style of improvisational rock performance that has truly never been bettered. But you could see Clapton’s point. Cream had already taken that line of attack about as far as it could go.

Others would follow – notably the American four-piece Mountain, whose 1970 debut Climbing! was indeed climbing the US chart. But for Clapton, it was time to reinvent himself – a trick that Bowie would later take to another level. Both Layla and The Man Who Sold The World were albums that would shape the course of rock over the decade that was just dawning – and far beyond.

Clapton and Bowie were outliers who, in their different ways, were both ahead of the curve in 1970. The industry was still figuring out how to market them. And rock audiences had yet to retune their ears to the different approaches that both were applying to a broader genre that was still under construction. For all the brilliance of their work that has been revealed over time, 1970 just wasn’t their moment.