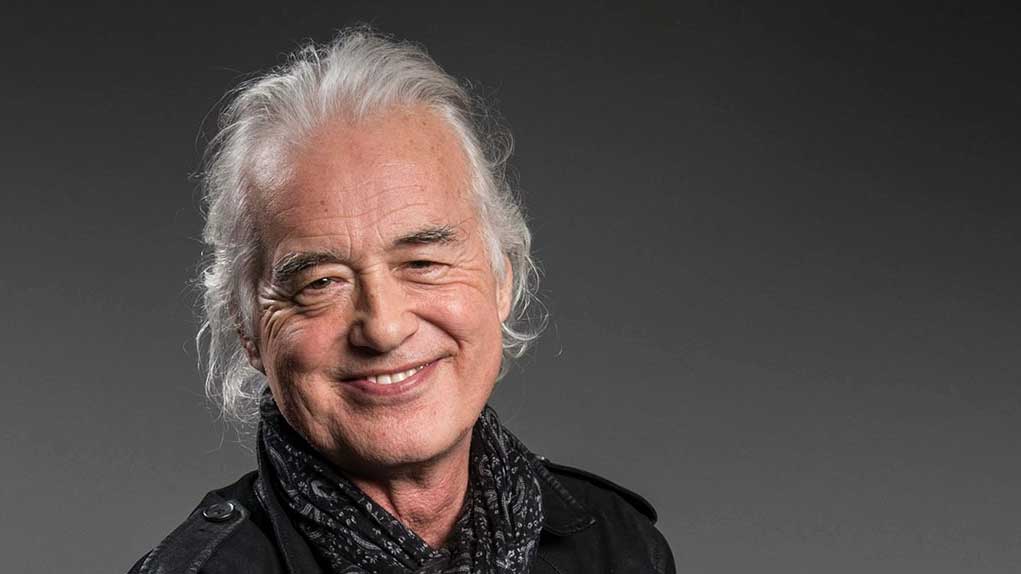

"We just went in and just destroyed San Francisco, and that was it": Jimmy Page on Led Zeppelin's historic arrival in America

Jimmy Page talks absent friends, superstar fans, bad reviews and the next best thing to playing with Led Zeppelin

In 2015, Led Zeppelin founder Jimmy Page spoke to Classic Rock about his life and work, from the first recordings he made as a naïve teenager to the legacy that rock’s greatest band leaves behind. He recalled the magic of Zeppelin's first time playing together, the battles with bootleggers and the press, the brilliance of the late John Bonham, and the joke song that backfired on him. And he explained why playing with the Black Crowes was the closest he’d come to replacing the feeling of Led Zeppelin.

When you think back to 1968, when you first put Led Zeppelin together, how soon did you realize that you had something unique?

It happened in the first rehearsal, which was in London, in Gerrard Street. I said we should play Train Kept A-Rollin’, but I think I was the only one who knew it. I don’t really know what else we did. But as soon as we played together, everyone knew instinctively that we’d never played anything like that before, or heard anything like that before. And it was just so right.

Had you already written songs for the band before that first rehearsal?

There was material I already had in mind, like Babe I’m Gonna Leave You and some other things. And by the time I got everyone in my house and we were doing steady rehearsals, we were working on Communication Breakdown and You Shook Me. Laying down that material, it was phenomenal. We knew just how good it was.

What did you have in Led Zeppelin that was different to other rock groups of that era?

In those days, you’d find really great groups built around one instrumentalist. In Led Zeppelin you had four master musicians. I know Cream had three, but to get four guys together, all at this high level, that was something else. To be honest with you, I knew the group was dynamite. From the rehearsals we did at my house, I knew what we had. And after we did the first tour in Scandinavia, I knew it would translate in a live capacity.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The first Zeppelin album was released in January 1969. What do you remember about the making of that record?

It was great how the first album was done – by playing it live in Scandinavia, to really oil it up before going into the studio. That way you were able really work it out before you’d recorded it. If you’ve got the benefit to do that, it’s a really healthy way to go into the studio, especially with guys who haven’t been in a studio too much beforehand. Also you had to record very thoroughly, and it was pretty ruthless – you couldn’t go in there wasting time, certainly with a new band.

What were you aiming for with that album?

You wanted to get in there and make the thing explode. You put all the chemicals together and it explodes out of the speakers. The word is chemistry, or alchemy. And that album was a complete picture, you know? So may ideas and combinations that people had never heard before. John Bonham had so much power and so much character in his playing, and there was some great keyboard playing from John Paul Jones. To get that album the way that it was, that was very cool.

From the very start, the band created a huge buzz in America.

We just went in and just destroyed San Francisco, and that was it. The first album wasn’t even out. And it just spreads like wildfire – that this band was just incredible, and then they hear the album…

By the early 70s, Led Zeppelin were the biggest band in the world, outselling the Stones. How did you deal with that level of fame?

If you’re talking about the time of the private jets and all that sort of stuff – do you mean that sort of lifestyle? Because other people were doing that, basing themselves out of cities and using a plane. It made sense.

I meant how you, as the leader of the band, coped with that pressure. Was Zeppelin’s manager Peter Grant the key to this – taking care of everything so that you could focus purely on the music and nothing else?

Yes, to go that far creatively, you needed somebody to be looking after the business side of it. And Peter definitely took care of the business side of it – outside of the making of the albums, certainly. But he and I went to Atlantic in New York in the initial stages, to do the original deal. And at the time of the fourth album, when we wanted to put that record out with no information on the cover – no band name, no title – Peter and I had an interesting meeting at Atlantic.

How did that go down?

When we got there, the Atlantic lawyers separated us. Peter was in one office and I was in another. They were saying, “You’ve got to have the name of the band on the cover.” I smiled and said, “You can print it on the inside bag, so that when people pull the album out they can see ‘Led Zeppelin’…” I was taking the piss, basically. Because they weren’t going to get the album unless it was under the circumstances we wanted.

You got what you wanted – and that album turned out to be one of the biggest-selling records of all time.

Yeah. But we were getting so much bad publicity at that time. That’s why we thought: okay, let’s put out an album with no information and let’s see what people think about that. Never mind what Rolling Stone says…

The bad reviews you had in Rolling Stone – did it hurt?

It didn’t matter. You could tell, even from the concert reviews, that they probably spent their time in the bar. They definitely hadn’t concentrated on what was going on. What was going on, right from that point in San Francisco, was that people were just flooding to see us, and that never stopped.

Do you remember Rolling Stone’s review of Bob Dylan’s 1970 album Self Portrait? It began, famously, with the question: “What is this shit?”

Yeah, well that’s what I would say about Rolling Stone. I wouldn’t say that about Bob Dylan.

But for you personally, were there moments when Led Zeppelin failed? Are there songs in which you hear the band struggling, or perhaps reaching for something that could not be reached?

I don’t think so. I can tell you how things were with Led Zeppelin. When we were working at Headley Grange, recording with a mobile truck, or if we were in the studio, booked for time, we would go in there and we would really work with what ideas we had. There would be things coming out of jams, on the spot. And if one had a riff and it didn’t quite make it, or if it sounded like something we’d done before, it wouldn’t be revisited.

So there are no Led Zeppelin songs that embarrass you?

No. None.

But there are some that sound a little throwaway. There’s one on Zeppelin’s last album, In Through The Out Door – the playful rock’n’roll number, Hot Dog…

Yeah. Hot Dog was just a bit of fun.

And earlier, on Houses Of The Holy, you did a reggae song with a phonetic joke title, D’yer Mak’er. It was a joke that was lost on your American fans.

In America they had no clue what it meant, and it was just boring to have to explain what it was. You’d think: why didn’t we name it something else? At least the Brits got it, thank God.

Are there Zeppelin songs you feel are underrated?

What would you say?

Poor Tom is one. Maybe it got lost on Coda, the outtakes album released in 1982 after the band split. But it’s a great track. Dave Grohl loves it: he said that it’s one of John Bonham’s best performances.

Yeah. He’s right. And okay, here it is with Poor Tom. I had an idea for the drumming in that song. I said to Bonzo, ‘This is what is.’ And I knew he’d got it within five minutes, maybe not even that. He’d got the syncopation in his playing. That’s what it was like playing with John. He and I were so in sync – it was so cool. You could be writing something and, bang, you knew exactly how it would all sound.

Another underrated song is For Your Life, from Presence. So underrated, in fact, that when Zeppelin played it at the O2 in 2007 – the first time you’d ever played it live – many reviewers thought it was a new song.

That was… interesting (laughs). The reviews for the O2 were wonderful. But in the euphoria, people thought For Your Life was a new number. They knew all the other things, but that one song they weren’t aware of.

I would suggest that anyone who didn’t know For Your Life should not have been at the O2 that night. Their ticket should have gone to a genuine Zeppelin fan.

Yeah, I think you’re probably right. But in context, it was so cool to do that song. It’s quite edgy to play. There’s a lot to remember in it, so many changes, unexpected changes.

Was it also hard to stay in the groove on that song, because you play it so slow?

To get the tension in it – yeah. It’s quite an intense groove on that one.

You’ve said that you were pretty nervous before the O2 show.

I always get nervous, but probably never more so than then. You only had one shot, for heaven’s sake. But we’d put a lot of rehearsal into it, so I knew it would work. And really, it was a great gig, which is why it was so important to me that we got everything right with the DVD of it (Celebration Day). It sounded so, so good. For people who didn’t actually manage to get to the gig, what they got as a DVD was not going to disappoint them. They didn’t get into the show, but my goodness that DVD is good.

And better than the bootleg DVDs that were on sale within days of the gig…

You know, there was a guy from Japan who filmed it. He was on the plane immediately to go back to Japan, and the DVD was out within a matter of hours, let alone days of weeks. It’s the same thing when you play in Japan. I know for a fact that if you do a tour there, you’re bootlegged instantly. So if you’re starting a tour, you’re warming up, you really don’t want to go over there and do a dodgy show. You’ve got to go in there with all guns blazing.

Surely the biggest problem is not bootleggers but fans filming gigs on their phones?

Oh yeah, everyone’s like that now. On the first Led Zeppelin tour we’d be doing stuff that was going to appear on the second album. But now, bands have to be so careful about playing new stuff in front of an audience. You’re confounded by YouTube.

Kate Bush found a solution. For her shows at the Hammersmith Apollo in 2014, she requested that fans did not film the performances, and it worked.

Did you see that concert? I did. And I can tell you: if somebody had held up a camera they’d have been lynched. There was such a feeling towards it. The people had so much respect for Kate.

You had your revenge on the bootleggers with the Led Zeppelin reissues – all nine of the band’s studio albums supplemented with previously unreleased tracks. Out of all that archive material, what for you is the very best of it?

I love the Bombay session from ’72 (featured on the new version of Coda). It was just Robert (Plant) and I that went out there. I was so mad keen to do something with Indian musicians. They were the equivalent of what you would now call the Bollywood musicians, except in those days it was really insular. They were classical players, and they’d never heard Led Zeppelin music before. The whole idea of the experiment was to see what it would be like for these ethnic musicians to translate from the guitar.

The first song you played with them was Friends, from Led Zeppelin III. Why that song?

When I’d written Friends, I’d thought of it in that sort of Indian style, with the complex rhythms from the tabla.

You can hear that in the original.

Absolutely! I thought we could do this song. They played it purely on their technique. It was so exciting. And because we were only in there for an evening, I didn’t want the moment to go, so I thought: right, let’s do something else. We had this great percussion: a tabla drummer and another playing a double-ended long drum. So I fired up Four Sticks (from Led Zeppelin IV), and these drummers were so technically adept, they just sailed through.

All of this additional material on the reissues was drawn from your personal archive. Is there more treasure that you have hidden away?

Yes. I have stuff that precedes Led Zeppelin as well – stuff that I did way, way back when I was a teenager, writing, trying experimental recordings at home, in a really sort of naïve way. Then, going on to when I was a studio musician, I have stuff from that period. And I’ve got lots of material from The Yardbirds.

Will any of this material ever be released?

Well, I started going through all this stuff, revisiting it with an idea of putting it all together in chronological order, to have a proper inventory of what it was – from Led Zeppelin and beyond. But once I hit the Led Zeppelin stuff, I just focused on that.

So in answer to my question…

For now, there is no answer.

What do you feel is the best record you’ve made outside of Led Zeppelin?

I don’t know. What do you mean by best?

Maybe the one that you most enjoyed making.

I had a solo album in 1988. Outrider. It wasn’t bad at all. I can still relate to it.

What about the records you made in the period just before Outrider? In the mid-80s, you recorded two albums with Paul Rodgers in your group The Firm, but that band seems to have been written out of history.

I enjoyed what I did with those albums. Paul is such a great singer. But I think, unfortunately, that The Firm’s second album (Mean Business) was one of those things recorded in the 80s that suffered a bit from the sounds of that time. The band was really good, but with that album you don’t get the full meat and potatoes.

And after that?

I enjoyed working with David Coverdale (for one album, Coverdale Page, released in 1993). What I really enjoyed doing was playing with The Black Crowes. That was phenomenal. There was only one downside. The set that we had was a mixture of Black Crowes songs and Led Zeppelin songs. So I was playing on their music was well.

But when it came down to putting together an album, their record company wouldn’t let them do a re-record. So that’s why that album (Live At The Greek: Excess All Areas, released in 2000) was mostly all Zeppelin stuff, with some old blues songs. It was really a bit upsetting, but nevertheless the Zeppelin stuff we did, playing it with them, was bloody marvellous. Just fantastic. I had a whale of a time.

Your love of music – is it still as strong today as it was when you were a kid?

I’m certainly very passionate about it. And it’s funny, really. I’m quite aware of the fact of being that kid who was on that bloody embarrassing TV thing when he was in a skiffle group when he was about twelve. But that passion that I had as a kid, it took me though the world of being a studio musician – and it was such a great schooling, you know? I learned to read music, and by the end of it I was doing arrangement and production. For an untrained musician, self-taught, it was so cool.

Did you always believe, as a young man, that you would be successful?

Oh my God. Not if I’d been thinking as an adult as opposed to a teenager.

Meaning what?

As an adult, you’d think: if you muck up, you ain’t gonna be seen again. You know, that pressure of not wanting to fail. But I just went in there and pulled it off. When I look back, I think that was quite something.

And when you think of what you went on to achieve with Led Zeppelin, what are you most proud of?

The fact that our music reached so many people. We couldn’t supply the demand of people wanting to see us. Even when we hadn’t played in England for a number of years and we played Knebworth (in 1980), there were record crowds for that time.

What was it about Zeppelin’s music that connected with such a huge audience?

It’s no one thing – it’s so many things. We touched on so many different areas of music. That’s why Led Zeppelin is such a vast, panoramic, all-encompassing thing. Over the years, you hear these artists that have been inspired by our stuff, and they’ve done something in the same sort of vein, but people can hear what we did first. Led Zeppelin is the forerunner, the catalyst, for a lot if ideas and movements. And the fact that this music has been so alive all through the years – young kids come to it, they learn from it – that’s absolutely brilliant.

The band is gone, but the music lives on…

That’s it, exactly. People are always telling me how important our music has been to their life. And that, really, is the whole heritage and the legacy of Led Zeppelin.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”

![Led Zeppelin - Ramble On (Live at the O2 Arena 2007) [Official Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/EYeG3QrvkEE/maxresdefault.jpg)