The musical and cultural bloodline of Louisiana-born, Delta-raised Lizzie Douglas (1897–1973), better known to history as Memphis Minnie, runs through the veins of every woman who’s ever picked up a guitar and rocked the blues.

A powerhouse singer, guitarist and songwriter whose raunch, skill and charisma challenged the male monopoly of down-home guitar blues, she was sufficiently formidable to best the majestic Big Bill Broonzy himself in blues contests held on his own Chicago turf. Bukka White rated her as “about the best thing goin’ in the woman line”.

It’s therefore bitterly ironic that the song with which this pioneer is most frequently associated in the rock era is one she neither sang nor wrote.

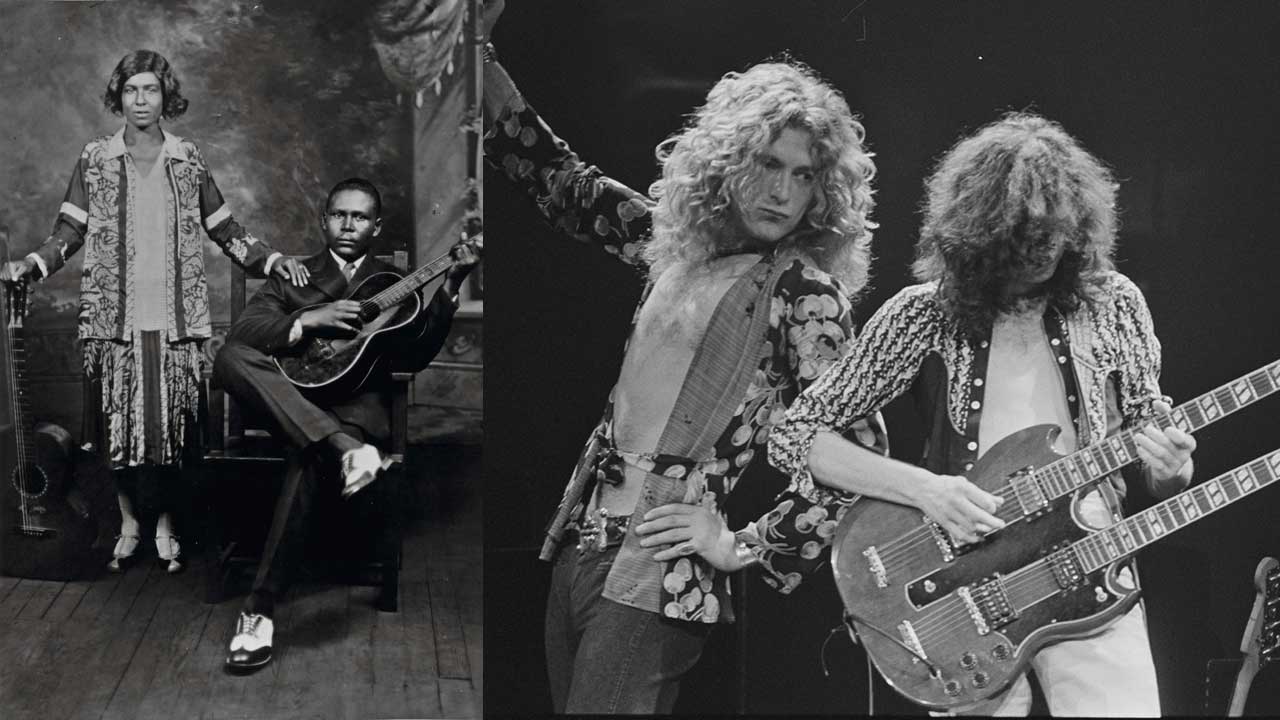

The composer credits for When The Levee Breaks – the closing track on Led Zeppelin’s multi-platinum fourth album (the rune-y one with Stairway To Heaven on) – read, ‘Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones, John Bonham & Memphis Minnie’.

The original dates back to 1929, and Minnie’s first-ever recording session. She was already a veteran of almost two decades of performing in jukes, bars and tent shows, with jug bands and on street corners, when she and her partner, Kansas Joe McCoy – a fellow singer/songwriter/guitarist, eight years her junior, with whom she’d hooked up a few years earlier – were talent-spotted by a Columbia Records scout, and the duo were whisked off to New York to record.

From that session came Minnie’s first classic, Bumble Bee. It was a huge hit, upon which Muddy Waters based his Honey Bee, just as, a little later on, Minnie’s If You See My Rooster generated a song credited to Willie Dixon and associated with Howlin’ Wolf and the Rolling Stones.

The NY session also reaped McCoy’s composition, When The Levee Breaks, sung by him and garnished with Minnie’s deft, sparkling lead guitar. It was credited to ‘Joe & Minnie McCoy’, though they didn’t marry until the following year.

The South is prone to flooding – as, tragically, we saw just in 2005 – and, not surprisingly, there’s been a whole raft of blues songs written on the subject over the years, ranging from Charley Patton’s High Water Everywhere and Bessie Smith’s Backwater Blues to John Lee Hooker’s Tupelo and Randy Newman’s Louisiana 1927.

Lyrically, at least, the original When The Levee Breaks is a proud part of that canon, but the drama of the lyric and the subject matter is somewhat undercut by the musical setting: Joe McCoy’s rhythm guitar is almost-folky mid-tempo ragtime, while Minnie’s intricate, dancing lead tempers the deceptive jauntiness with melancholy minor-scale inflections. McCoy’s lead vocal is plain, almost matter-of-fact.

At the time, the song wasn’t that big of a deal: merely one of hundreds of nifty but little-more-than-pleasant country blues sides of its era, albeit with a hauntingly evocative lyric. It wasn’t a classic, though it might have been if Minnie had sung it rather than McCoy. Her singing and guitar-playing were extraordinary, his merely serviceable; McCoy’s main strength was as a songwriter.

The couple split in the mid-30s. Minnie’s next – and last – husband was another musician, Ernest Lawlers, aka Little Son Joe; they stayed together until his death in 1961.

Minnie was a rough, tough, fully-qualified survivor – she’d had to be, having made her own way since leaving home at 13 – and her career thrived until failing health forced her into retirement in the early 1950s.

Throughout the 30s and 40s she enjoyed numerous hits (the best-known of which are Hoodoo Lady and Me And My Chauffeur, the latter a folkie favourite in the 60s, covered by Jefferson Airplane on their pre-Grace Slick first album) and took up electric guitar as early as 1942. A 1949 session for the Regal label features the kind of raunchy, rocking electric Chicago blues which even Muddy Waters wouldn’t get around to recording for another few years.

Until the 1960s’ folk/blues revival, Minnie’s music was rarely heard, except amongst elderly black folks and white folkie collectors of mouldering 78s, though her work was treasured by the likes of the young Bonnie Raitt and Britain’s Delta-blues specialist Jo-Ann Kelly. And also, with fateful consequences, by a Kidderminster kid named Robert Plant.

And there the matter rested until 1970, when Led Zeppelin were starting work on what would be their fourth album, following up an acoustic-dominated third album which had (initially, at least) failed to match the success of their first two. Among the songs Robert Plant presented for consideration by Jimmy Page – the ultimate arbiter of All Things Zeppelin – was When The Levee Breaks.

The band tried it out during sessions at Island’s Basing Street studio. It didn’t work. Then, once their recording locale had shifted to the country retreat of Headley Grange in east Hampshire, they tried it again. This time it worked. Lord, how it worked.

The Led Zep version of When The Levee Breaks is one of the band’s authentic masterpieces of transforming acoustic country blues into monolithic rock. Words like ‘epic’ and ‘awesome’ have become drained and devalued by sheer repetition, but here they’re entirely justified. No heavy band ever played funkier, and no funk band ever played heavier.

Structurally, it’s one of the band’s simplest pieces: they jettisoned the original’s conventional 12-bar structure and played the song pretty much all on one chord, except for the serpentine riff which periodically inserts itself into proceedings. (They also retooled Joe McCoy’s original lyric, dropping some of his verses and adding new words of their own.) By contrast, it’s one of Jimmy Page’s most complex productions.

“You’ve got backwards harmonica, backwards echo, phasing, and there’s also flanging, and at the end you get this super-dense sound, in layers, that’s all built around the drum track,” explained Page. “And you’ve got Robert, constant in the middle, and everything starts to spiral around him. It’s all done with panning… each 12 bars has something new about it, though at first it might not be apparent. There’s a lot of different effects on there that at the time had never been used before. Phased vocals, a backwards echoed harmonica solo…”

Most important of all, the basic track was slowed down, giving it even more weight and murk. Lawdnose how many guitars Page overdubbed: layers of Mizzippi-mud Les Paul grunge, topped off with a clean, ringing slide guitar. It’s both huge and claustrophobic: Plant’s voice in perpetual danger of being overwhelmed by the immense natural forces swirling around him.

And, of course, it begins with one of the greatest drumbeats ever recorded: John Bonham playing one of the simplest backbeats imaginable, but with his trademark combination of funk snap and timing and rock power and weight.

If Bonham had never recorded anything else, those few bars alone -– the most-sampled drum groove in musical history not bitten from a James Brown record, used by everyone from the Beastie Boys (1986’s Licensed To Ill opens with Bonham), Dr Dre and Eminem to Björk, Massive Attack and Mike bleedin’ Oldfield – would have ensured his keys to the kingdom.

Famously, it was recorded by setting up the drum kit in Headley Grange’s stone-walled hallway with engineer Andy Johns hanging a single stereo mic from the second-floor landing of a three-storey staircase, and rendered even more weighty and menacing when it was enhanced with compression and echo in Page’s mix.

The lessons thus learned were later applied, equally effectively, to two songs associated with Blind Willie Johnson, the terrifying master of gospel-blues slide guitar: In My Time Of Dying (on Physical Graffiti) and Nobody’s Fault But Mine (on Presence), but When The Levee Breaks was the breakthrough.

So… who wins? Well, we have to give this one (not without some regret) to the limeys. As we’ve said, their radical reconstruction of a cool, nifty but ultimately unexceptional old blues song was a genuine innovative expansion of musical possibilities: a true masterpiece. Joe and Minnie’s recording, for all its charm and dexterity… isn’t.