"I did have a multitrack tape of that, but it got mislaid": The secret history of Led Zeppelin’s lost masterpiece

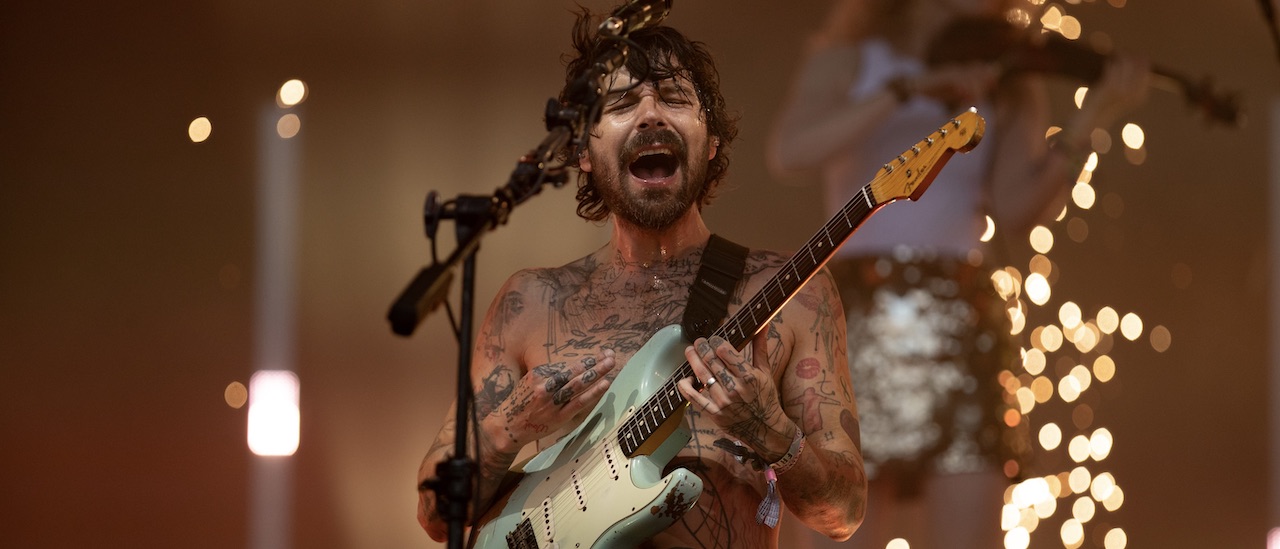

Jimmy Page dug up several unheard gems for his deluxe Led Zeppelin reissues. But there's one song that still remains unreleased

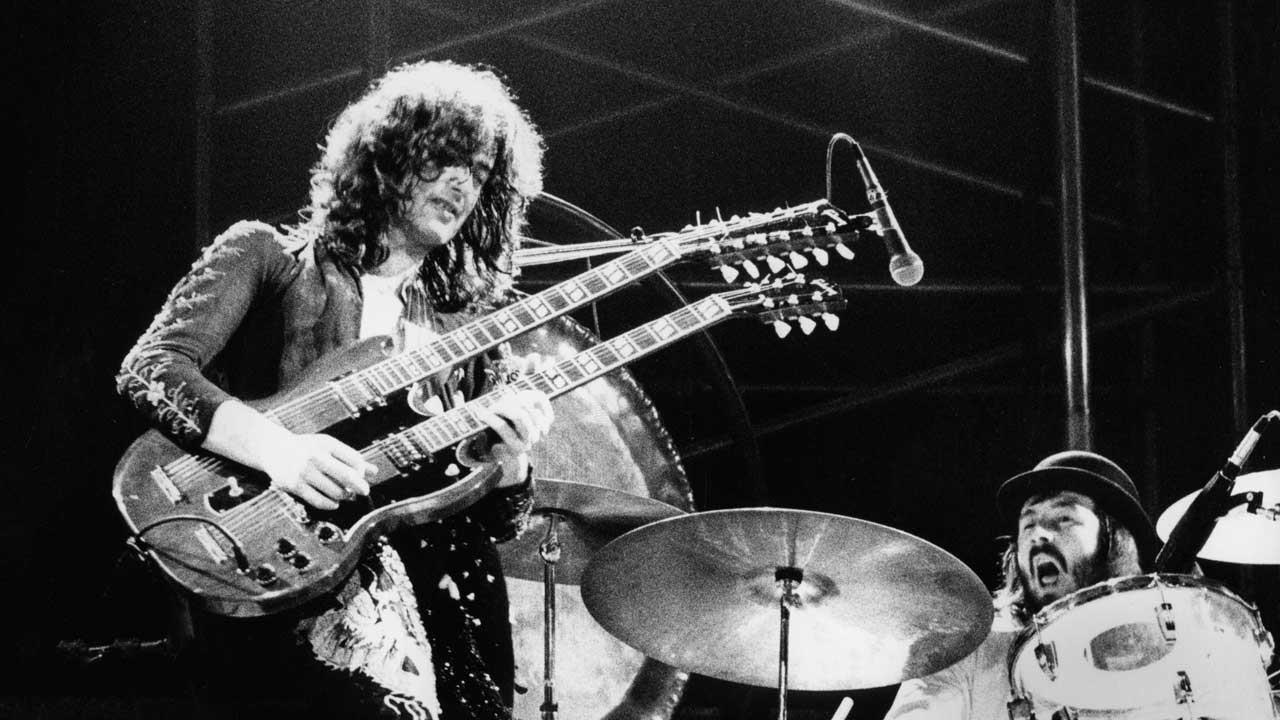

The fertile sessions for Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti album produced a number of landmark songs, including In My Time Of Dying and Kashmir. And among them was another track that had the potential to be a Zeppelin classic. An ambitious, virtuoso instrumental titled Swan Song, it was sketched out and partially recorded during the album sessions but, frustratingly, never completed – even though, like many of his ideas, Jimmy Page would not quite let it rest.

The seeds of Swan Song were sown in early 1974 when Zeppelin reconvened to begin work on Physical Graffiti at Headley Grange, the 18th-century workhouse in Hampshire where they’d recorded their fourth album.

The band had endured a crisis the previous autumn when John Paul Jones announced that he was fed up with the relentless touring and was planning to quit the band. He even suggested, albeit with his tongue firmly in his cheek, that he was considering becoming choirmaster at Winchester Cathedral. It took all the efforts of manager Peter Grant to talk him out of it.

But by the time the four band members got back together they were once again firing on all cylinders. Reunited, they began pooling ideas. “Some of the tracks we assembled in our old-fashioned way of running through a track and realising before we knew it that we had stumbled on something completely different,” recalled Robert Plant.

By contrast, Page had grand plans for a lengthy new track he was calling Swan Song. The guitarist had already plotted out the instrumental piece at his home studio in Plumpton Place, East Sussex. Even at that early stage, his vision was clear. According to Page, it featured “a number of sections and orchestrated overdubs”.

The track was broken up into sections, two of which were recorded in late February 1974 (and which can be heard on various Zeppelin bootlegs and on YouTube). The first part opens with Page’s drifting acoustic guitar, before the John Paul Jones/John Bonham rhythm section kicks in with the sure-footed syncopation that characterised their greatest work. The second segment commences with Page again leading off, his descending riff hinting at the song’s majestic potential. Tantalisingly, he would later reveal that this epic-in-waiting would not necessarily have remained a purely instrumental track – there were plans to add other sections and even lyrics.

So why did they leave the piece unfinished? The simple truth is that Zeppelin’s creativity was at an all-time high during the Physical Graffiti sessions. At the same time, they had also been working on Ten Years Gone, another lengthy track that incorporated similar guitar orchestration. Faced with an abundance of quality material, they could afford to leave Swan Song for another time. Consequently, it was Ten Years Gone that ended up on Physical Graffiti.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

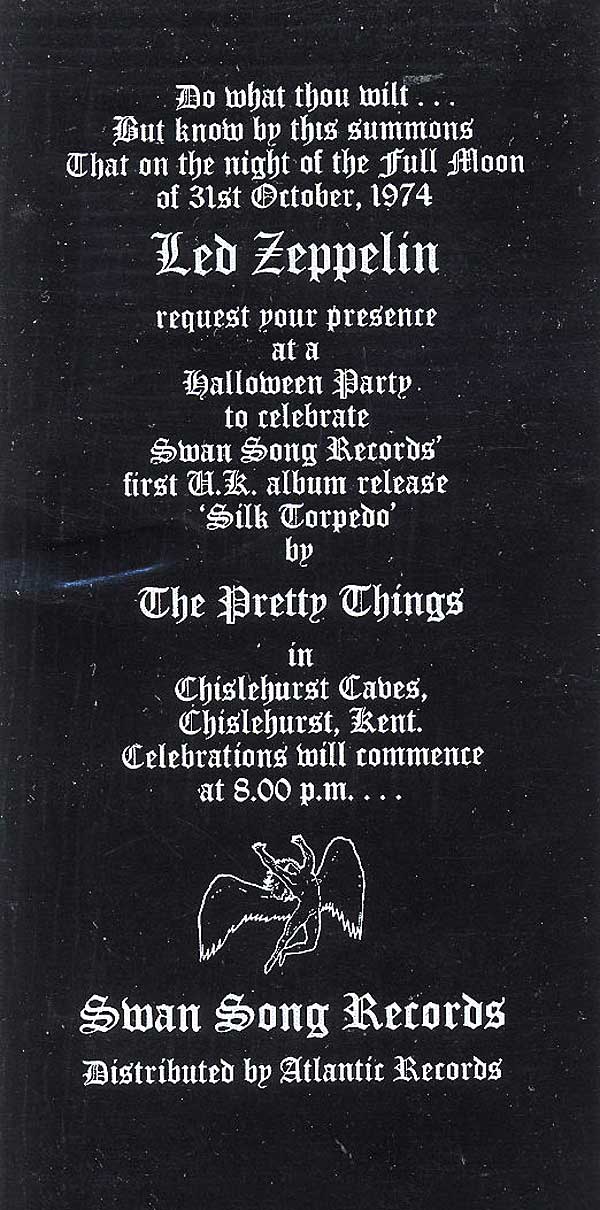

But the Swan Song story didn’t end there. Zeppelin were planning to launch their own label and rumours abounded that it would be called Shag or Slut Records – a lewd reference to their notorious on-the-road antics. Instead, at a press reception in New York on May 7, 1974, it was announced that the new label would be called Swan Song, after their unfinished song. “I’d been recording this long instrumental and somebody shouted: ‘What’s the title?’” revealed Page. “I shouted back: ‘Swan Song’. And everybody stopped and said what a good name that would be for the album. From there it got carried over to being the name for our label.”

Never one to let go of a good idea, Page talked about returning to the incomplete song to finish it off. “I’ve spoken before about a long piece I’d written,” he said in 1976. “I wanted to orchestrate the guitar and put it through various treatments. The original idea was to have four sections coming back to the same theme each time. There would be four separate melody lines dealing with the seasons. Robert will do the lyrics. I know I can work the whole thing out from the trial runs I’ve laid down. It’s a really exciting prospect.”

Page continued to incorporate elements of Swan Song into his live improvisational piece White Summer/Black Mountain Side during Zeppelin’s 1977 tour. It would reappear again during the band’s Knebworth shows in 1979, and even as late as their final European tour, in 1980. Had Zeppelin not disbanded following the death of John Bonham on September 25, 1980, there’s every chance that Page would have gone back to work on the song in the studio.

But even that wasn’t the end of his great lost opus. Page’s first major live appearance following the dissolution of Zeppelin was as part of an all-star nine-date US tour in 1983 in aid of the ARMS charity to help multiple sclerosis-stricken ex-Small Faces bassist Ronnie Lane. With Paul Rodgers on vocals, Page performed a lengthy song called Bird On A Wing, which featured some chord structures that clearly dated back to Swan Song.

By the time Page and Rodgers formed their blues-rock supergroup The Firm, it had been revisited once again. “It was reworked with Paul Rodgers, who supplied some inspired lyrics, and it became Midnight Moonlight,” said Page, referring to the song which closed The Firm’s self-titled album in 85.

Today, Swan Song has passed into Zep legend as one of the band’s great lost masterpieces – albeit one that has, tantalisingly, filtered into the ether in various incarnations.

As with other unfinished Zep treasures such as Sugar Mama and Fire, it’s difficult not to wonder how significant Swan Song would have become had they actually finished it. And we'll probably never hear an official version of what they did come up with.

"I did have a multitrack tape of that, with orchestration and Mellotron and all this stuff, but it got mislaid," Page told us in 2015. "I don’t know what happened to that."

Dave Lewis is a freelance journalist and the editor and publisher of the Led Zeppelin magazine and website Tight But Loose, and author of several books on the band. Through the magazine and books, the Tight But Loose website and his Facebook page, Dave's objective remains to continue to inform, entertain and connect like minded Led Zeppelin fans new and old throughout the world – bringing them closer to the greatest rock music ever made.