"We had to fight to put that one out but eventually everybody got it": Keith Richards picks the Rolling Stones album he'd play to a 14-year-old just getting into rock music

Rolling Stones legend Keith Richards on Altamont, writing with Mick Jagger, and his advice for young musicians

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

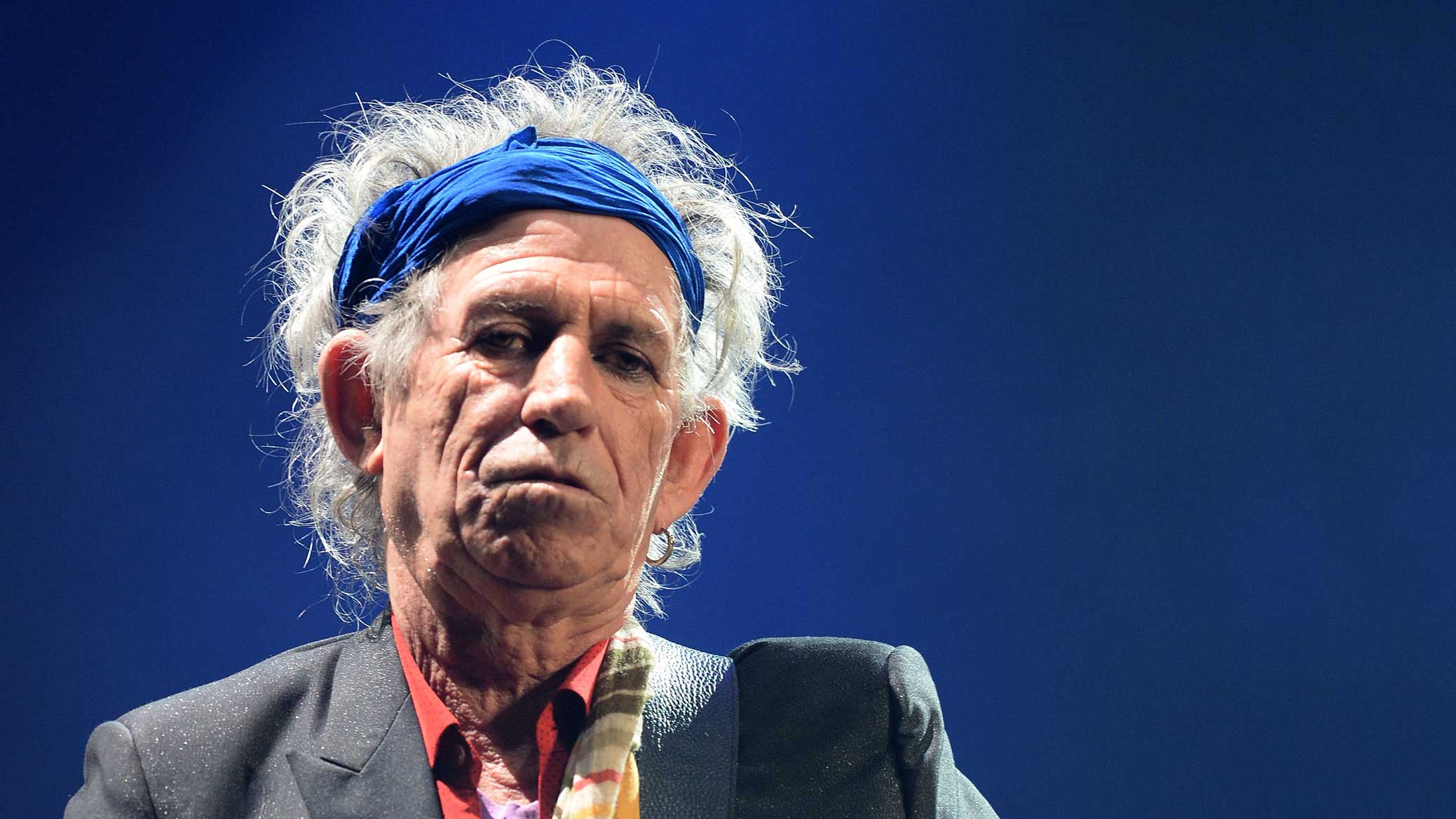

In 2014 Classic Rock Magazine published its 200th issue and set itself a herculean task: a double-size, bumper issue containing 200 interviews with 200 different musicians. Of course, no such undertaking would be complete without Keith Richards, the seemingly invincible Rolling Stones guitarist.

Do you remember a time very early on when you thought, “This is it, we can actually do this…”?

That’s difficult, but the first time was when I got into a recording studio – that was like entering the portals of Heaven and it grew from there. But after Satisfaction, we all felt we had a chance of a career.

Article continues belowThere was no career path for young bands like the Stones or The Beatles. You were just winging it?

Winging it is the right description, and making it look like you knew what you were doing. That includes everybody, like promoters. You made it up as you went along.

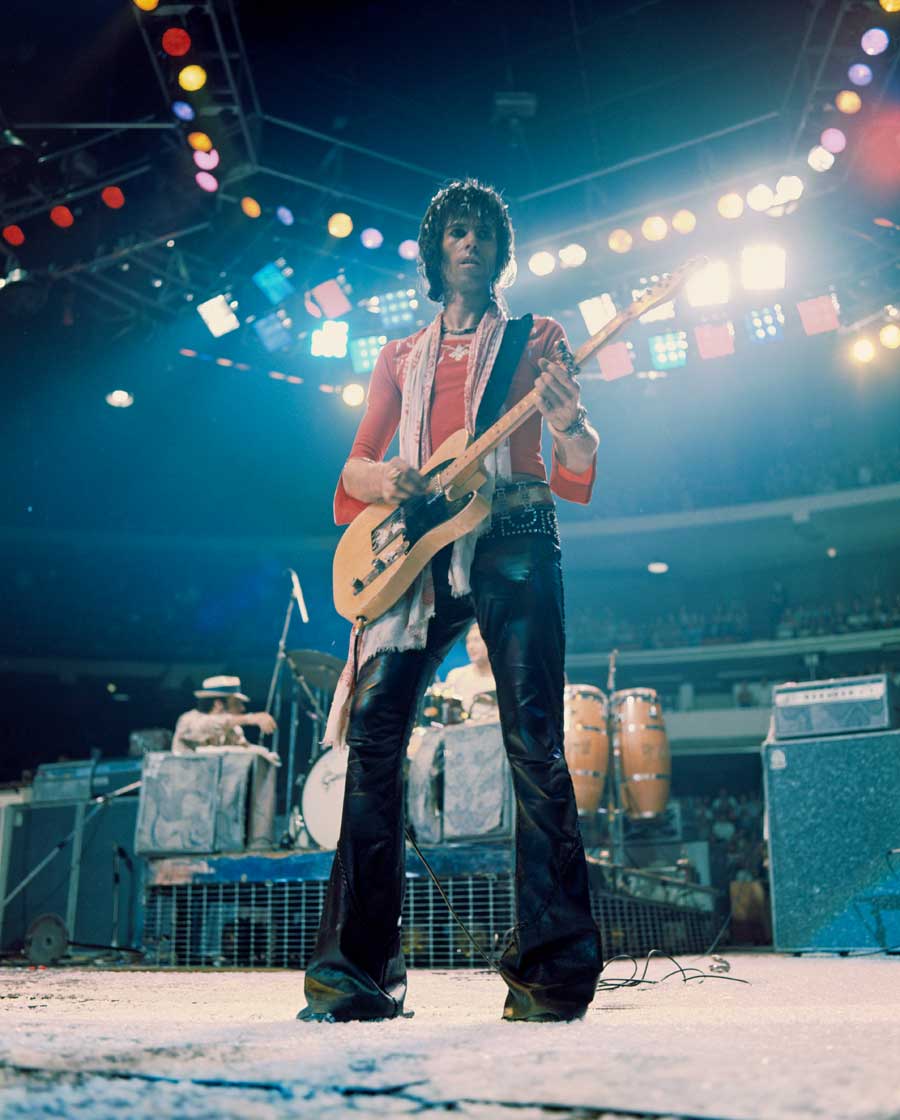

Looking at documentary footage of your early shows, they were chaotic. At the disastrous Altamont festival in ’69, fans, Hells Angels and even a dog were on the stage at some points. This was all very amateurish in reflection.

Ramshackle, man. That show was thrown together by the Grateful Dead because we had no experience of that and it was their speciality. So we arrived and thought, "This is the way it’s done."

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

But would never be done that way again?

Oh no, I draw a line there, man.

You and Mick have written some of the most enduring rock songs of the past many decades. But do you not cross paths often enough to continue the writing process today?

We absolutely do. We always have some work on the go and it’s about getting off the hiatus and back in the studio.

So do you write and record at home regularly but just leave all the songs on the shelf?

It all happen in dribs and drabs really. When Mick and I are on the road, we put ideas together and one thing leads to another. Playing live gives songwriting and recording more impetus, so I’m hoping we can come out with something great over the next few months.

For your fiftieth anniversary, you brought back guitarist Mick Taylor. How did that come about?

Everyone was going on about the fiftieth anniversary and we thought, well, there’s still a couple of Stones around who might want to join in. [Former bassist] Bill Wyman did some gigs in London along with Mick Taylor, but dropped out because he doesn’t like flying. So we said to Mick: “Do you want to continue?” and he said: “Yeah.” Ronnie [Wood] and I have a great time because now there are three guitars, and that gives us a bit more room to manoeuvre. That’s much more fun.

Does it surprise you that everybody is still keen to play?

I never doubt it. It’s finding everybody in the right mood at the same time. I catch them when I can and I’m the one who’s up for it. I’m always up for it, they can count on me.

A setlist for the Stones has to accommodate what an audience might want, but you still pull odd songs in.

One of the things that has cropped up during the tour this time has been throwing things in, or even asking for requests. I like to keep it as free and open as possible and we never stick to a totally fixed set anyway. I like to leave as much room as possible for experiment. Nothing in rock’n’roll has to be nailed down.

Where once audiences would come on the basis of the Stones’ notoriety, these days you capture a broad demographic drawn for the music and sense of the event.

I think we just carried the generation along with us and some of the younger ones still pick it up. It’s hard to put your finger on it. You expect to be rejected by the next generation because that’s what they do. But there seems to be some thread in what we do that busts through all that.

If you had to point to any album to explain the Stones to a 14-year-old who is getting into rock music, which one would you choose?

I’d say Exile On Main Street, mainly because it’s a double album so there’s more range on it. But it also is the pointer.

The one that at the time people said was poorly recorded but is the one which has risen to the top?

Yeah, it’s amazing. We had to fight to put that one out but eventually everybody got it.

And now everyone has a copy. Their Satanic Majesties… has had a bit of a resurgence for young people, possibly because for them it’s removed from the context of its time and so they’re just hearing the experimental quality of the songs. Does that surprise you?

It does a bit because it’s always been an oddball album in the whole line-up, probably because of some of that acid. But over the last year or so we’ve noticed a lot of interest in that album too. I’m not sure we’d put it on our list of favourites, but there are moments on it which stand out: She’s A Rainbow, 2000 Light Years From Home.

Do you ever listen to your old records?

Oh yeah, I do. If I hear the Stones it’s usually on the radio and by accident, but sometimes it makes me go back and listen to something I haven’t heard for a while. When we’re rehearsing we listen to just about everything we’ve ever recorded in order to find out how we originally played it, and to pick the essence out of it.

It’s a long history and I guess you do need to remind yourself of it from time to time.

Oh yeah, you need a reminder of some of the more obscure tracks.

You’re a history buff. Have you read anything especially interesting lately?

Somebody gave me Max Hastings’s latest book, about 1914 [2013's Catastrophe: Europe Goes to War 1914]. There’s some interesting stuff in there about how the First World War built up, and who screwed up first. Catastrophe is what it’s called, which I thought was a great album title.

Or a lifestyle.

[Laughs] Yeah, tell me about it.

If you were to give out advice, what would you say a young musician just starting out needs?

Perseverance. If you really want to do it and you hit brick walls, just dust yourself off and keep going.

As you’ve done, even after that holiday in Fiji in 2006 when you slipped from a tree just days after playing in Auckland.

I came right back to Auckland. Dr Andrew Law saved my bacon.

While you were having neurosurgery, I was asked to write your obituary, just in case.

Put that on the backburner for a while.

In it, I quoted something that Charlie Watts once said about you, which I always liked: "There’s something about music that likes being around Keith."

Oh, bless him. I’ll wear it like a cloak.

Graham Reid is an award-winning New Zealand journalist, author, broadcaster, and arts educator. His music and film reviews have appeared in The New Zealand Herald since the late 1980s. His website, Elsewhere, provides features and reports on music, film, travel and other cultural issues. He is the author of two travel books, and has written for Billboard, The Listener, The Australian, Metro, Art News, Real Groove, Idealog, Audioculture, Life & Leisure and Weekend.