So it happens like this. Mikkey Dee, Motörhead’s drummer, is in his car, somewhere in Sweden, taking his daughter to a dance class. On the other end of the phone is the man from Classic Rock, bombarding him with all manner of daft and impertinent questions.

\So what would you ask him then, if you were interviewing him?

There’s a long pause. The sun goes behind the clouds. “Yeah, I’m not sure about that,” he says, quietly. “I leave that stuff to you guys.”

No, wait, he says. He does have one.

And then it happens, the best question of them all, the one that reverberates throughout this piece and strikes at the very heart of the band’s existence.

“I think, after all he’s been though, I’d say this: ‘Lem, when are you going to get sick and tired of feeling sick and tired? It’s time you started to take better care of yourself’.”

If Motörhead are going to continue – and that’s what all the band want, he says – then all of them, but especially their spiritual leader and founding member, “need to get better at preserving who we are. We’re not 28 anymore. We need to look after ourselves.

“We can’t carry on the way we’ve been going – touring non-stop, playing every city in every country and not taking care of ourselves. It takes its toll.”

The atmosphere, previously jovial and knockabout, turns serious. There’s another pause.

“Good luck to you though, when you ask him that,” he laughs. “He might just tell you to fuck off.”

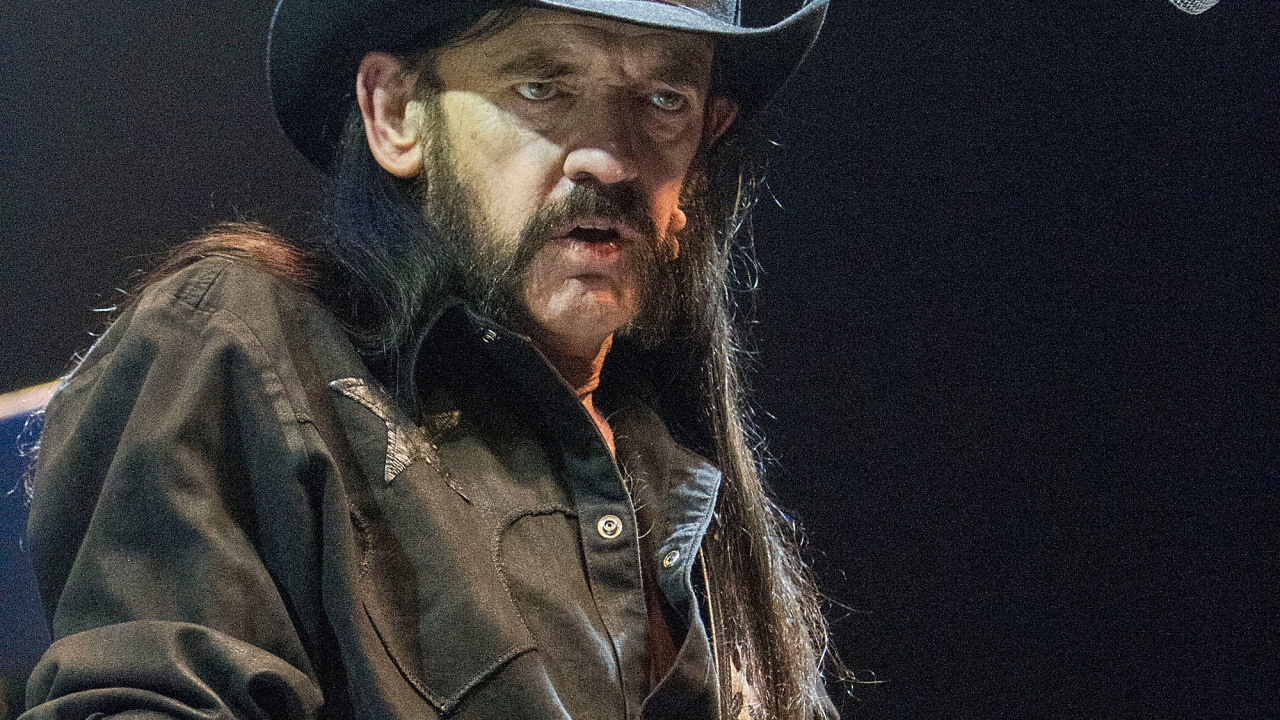

Mr Ian Fraser Kilmister is 67 years old. If there had been no Motörhead, no Beatles before that, no Elvis, no rock’n’roll, no desire to rebel, then maybe Lem would have slotted into a humdrum life and he’d be lining up with the old men outside his local post office on a Thursday morning to collect his pension, grumbling about the weather, in tight black jeans and a leather cowboy hat. Imagine that.

Instead, here he is: the baddest, most unflinching motherfucker in rock’n’roll – still standing, still playing a low-slung Rickenbacker bass on his hip, still doing it.

He has Grammys and gold discs, laminated magazine covers and all manner of music gongs. They don’t mean shit, he says. It’s not about that. It never has been.

What matters today is what mattered when he put Motörhead together in 1975, as a raucous three-piece version of The MC5.

“If we had a plan, that was it. Playing loud rock’n’roll, straight from the fucking shoulder,” he growls. “That’s what we’re about. I don’t care about the awards. I care about that hour-and-a-half onstage every night, and the kids who slog their way through life and come to our shows. It’s my job to make them stand a foot taller.”

That’s what it’s about, he says. He rattles through it nonchalantly, like it’s a shopping list. It sounds like a battle cry.

This year, there have been times when that battle has seemed a little bit harder to fight. Lemmy, the old heavy metal warhorse, has not been well.

It’s 10pm our time when we’re due to chat, 2pm in sunny Los Angeles, where Lemmy now lives. The phone rings in his West Hollywood apartment. There’s no answer. This continues for 20 minutes.

Lemmy, it transpires, is still in bed. The interview is put back an hour. “Sorry about that,” he says, sounding like Darth Vader through a broken megaphone. “Long old day.”

Lemmy has been putting the finishing touches to Motörhead’s new album in downtown Los Angeles. Called Aftershock, it’s the band’s 21st studio recording.

It’s good, he promises. Really fucking good. You’d expect him to say nothing less but still, he says it with such conviction that it brooks no argument.

“I hate it when bands have a new album out and they all say, ‘This is our best album ever, man, it really is’,” says Mikkey Dee. “But this is a good one.”

Produced by long standing knob-twiddler Cameron Webb, it’s more varied than previous releases, says Lemmy. “There are a few surprises on there. I hope people will like it.”

Ah fuck it, he says. “I’m being modest. It’s got everything a rock’n’roll person could wish for.”

What Lemmy should be doing is convalescing; putting his cowboy boot-clad feet up and taking it easy. He finds that hard.

Lemmy has been ill this year. A European tour – with shows in France, Germany and Russia – was cancelled earlier this summer when doctors discovered an unspecified haematoma, a pool of leaked blood gathered in his muscles.

Bah, he says about that. “It was nothing. I’m over that.” That’s not all, though.

There’s the legacy of the type-two diabetes, diagnosed more than a decade ago, and the defibrillator fitted earlier this year to iron out the uneven bumps in his heart. 2013 has been a rough ride for the captain of the Motörhead ship.

And yet you get the impression that it’s not the physical aspect of being ill that has sucked the wind from his sails – it’s the more insidious emotional and mental anguish.

In 37 years, Motörhead have cancelled a handful of shows. It rested uncomfortably on Lemmy’s shoulders. He felt guilty, says Mikkey, like he was letting people down.

“I don’t like doing that,” says Lemmy.

The scrubbed tour is not the real concern here, though. It’s the symptom of something more serious, the side effects of a life lived at breakneck speed. Lemmy lived fast, but didn’t die young. He didn’t expect to be here at 68. He didn’t expect to be here at 30, he says.

It’s a medical miracle and rock’n’roll triumph that he is. What he’s finding, at this late stage of the game, is a newfound fragility. He is not made of steel, after all. He does bleed. He is not immortal. For 30 odd years, he assumed he was.

People are telling him to slow down. He knows they’re right but that doesn’t mean he likes it.

“It was the same when people were telling me to stop smoking. ‘You’ve got to stop smoking, Lem’, they kept saying.”

“Fuck you,” he kept telling them back. “I don’t like people telling me what to do,” he says, “even if they might be right.” The constant, if well-meaning, chorus of voices telling him to stub out the cigarettes made him want to smoke more.

He quit, finally, a year ago. He did it on his terms, when he was ready. “I was having breakfast one morning, coughing and hacking my way through a cigarette and I stopped and thought: ‘What am I doing here?’” He hasn’t had one since.

Motörhead are at a big metaphorical crossroads. We all know what happens to rock stars when they end up there. Slowly, age is catching up with Lemmy, tapping him on the shoulder and whispering its sage advice. He knows he should listen. But who is it, this thing called age, to tell him what to do? He’s still here. He’s still rocking and rolling and rolling and tumbling and we love him for it, don’t we? Lemmy – the survivor, the road warrior, the man who survives on Jack Daniel’s and amphetamines, still doing it at 67, the leader of the loudest rock’n’roll band in the world. At some stage though, if he, if Motörhead, are to carry on, then Lemmy needs a new script. You get the feeling his head and his body know this, but his blackened heart is having a tough time accepting it.

He is not, he admits, a young whippersnapper anymore. Age has started to take its toll. The diabetes has affected the circulation in his legs. They stiffen and ache if he walks too far. His back hurts if he stands for too long. “But I can still stand at that mic every night and play my songs,” he says. He takes two pills for his diabetes every day. That’s under control. “I wouldn’t know about the defibrillator if it wasn’t for that fucking lump in my chest,” he says. “I’m getting better. By the time this article is out, and the tour comes around, I’ll be all right. I’ll be ready.”

People said to me before this interview that this might be your last album.

“Really? Who said that? I’ve never said that. Phil has never said it. Mikkey has never said it. We plan to go on. Maybe, if we can’t tour anymore, we’ll just make albums. We’ll be like The Beatles after 1966.” He launches into a long chat about The Beatles, his favourite band. He can’t decide which one of their albums is their finest: With The Beatles, maybe? Abbey Road? Revolver? He saw them way back in 1962 at The Cavern. He learned to play the guitar by playing along to their first album.

“I was Jimi Hendrix’s roadie,” he says. “My rock’n’roll credentials are fucking impeccable.” Scaling it back. It’s an idea that’s been quietly tossed around for some time in Motörhead’s inner sanctum. This year’s events have only served to make it a necessity, rather than some kind of idle pipe dream. If Motörhead are going to carry on, they’ve got to change the way they do things. Bigger shows, fewer cities, a bit less travelling perhaps.

“You know, maybe it’s time people came to see us this time,” says Mikkey, “rather than us travelling to them. We’ve never done that. Other bands do it. You know they do. Maybe it’s time we did.”

It seems an obvious solution. There’s one stumbling block, however – and that’s the man at the front of the stage, the one who started all of this. He says he wants to do a bit less, play fewer shows, fly on fewer planes and not spend so much time cooped up on the back of a tour bus. His body is telling him it’s time. They’ve discussed it, he says. His head knows it’s true.

I wonder if he knows how or where to start, though. Lemmy likes touring. He lives for the road. “I don’t have family, young kids at home who miss me when I’m not here. It’s hard for Mikkey, I can see that. But I like the road life. I like playing. I don’t want to stop that.”

Are you a workaholic? “I’m a roadaholic. When I’m not on the road, I miss it.”

They played the Wacken open air festival in August. They shouldn’t have. It had been cancelled along with their European tour.

“And then I found myself in Berlin that week, it wasn’t too far away, so I said, ‘Bollocks – we’ll see if we can do it’,” says Lemmy.

It was a bonus set, really, says Mikkey. It was 35 degrees in Germany that day. Bands half their age were wilting from the heat. “I was worried about Lem,” says Mikkey. “He doesn’t like it that hot.”

Much has been written of Motörhead’s brief appearance at Wacken last month, including a rumour that seemed to flood every crevice of the internet the following day that Lemmy had played the show, then collapsed and died.

“I’m used to that,” he laughs. “I read my own obituary 20 years ago in a French magazine.” There was a big picture of him and a headine that stated: ‘Lemmy Morts’.

It was all crap, says Mikkey. “We didn’t have to play, but we did. The promoters were not angry with us. They were delighted we gave it a go. We wanted to do it. The truth is Lem had been poorly and he hadn’t recovered. But we gave it a go because that’s who we are.”

Reports of death, ambulances, angry promoters, booing fans – it’s all bollocks, says Mikkey.

“Put that in your piece,” he says. “I’ve read so much bullshit about Wacken, it would be nice to put the record straight. We did it when we shouldn’t have done it. It’s fucking stupid that some people are criticising us for that.”

There have been 11 different Motörhead line-ups since the band’s inception in 1975. This one – Lem, Phil Campbell, Mikkey Dee – has survived the longest, made the most records, performed the most shows.

How have they done it?

“We trust each other,” says Mikkey. “And we’ve matured. Lem has mellowed. I’ve mellowed. We’re not kids anymore. Motörhead is more of a democracy than people think.”

What’s Lemmy’s best characteristic?

Mikkey: “Lemmy’s best characteristic is also his worst: it’s his stubborn determination.”

What do you mean?

“His refusal to compromise has made the band what it is today,” answers Mikkey. “So I have huge respect for him for that.

“But… I don’t know… when you’re the one that has to deal with his stubbornness… man, it’s hard. There have been times when I’ve suggested things or Phil has suggested things, good things that we could have done, and Lem just shakes his head.”

Unsurprisingly, Lemmy doesn’t quite see it like that. “It’s not that I might not like what they’ve suggested – it’s just that I don’t think it’s right for Motörhead.”

It’s more of a democracy than you think, this band, he adds, “but I still get the final say on that.”

They get on badly when they’re on tour, he adds, half-joking. “It only really clicks into place for those two hours on stage. Off stage, on a bus, the smallest things can get on your tits, regardless of how well you get on. Even the way someone breathes can drive you insane.

“All I ask for, if you want to be in this band, is that you work hard and you show a modicum of respect. I don’t mean kowtowing, just respect. You respect me, I respect you, and we respect who we are and what we do.”

Is that how it is?

“Yeah. We all pull together. We’re all heading the right way.”

It wasn’t always like this. In 1982, when Fast Eddie Clarke left the band, Lemmy chose former Thin Lizzy axeman Brian ‘Robbo’ Robertson to fill the vacant guitarist slot. Robbo made the Another Perfect Day album and stayed for the tour. It was a mistake, says Lemmy.

“I’ve enjoyed all the line-ups – but not that one. That was the lowest point in our career.”

Robbo’s a great guitar player though, isn’t he? “Yeah, he is – but he was always out of it. It was constant hard work and he just wasn’t right for Motörhead. He didn’t want to carry the load.

“I remember he turned up to one show in fucking bright green shorts. I had one of the Hells Angels leaders come to me and say: ‘Who’s that fucking freak in the green shorts? I want to kill him’.

“‘You’d better not do that,’ I said. ‘He’s our guitar player’.”

Lemmy and Robbo haven’t spoken since the guitarist left the band in 1983.

He’s in touch with other ex-Motörhead members. “Eddie called a couple of weeks ago to tell me that Mick Farren [former musician and Classic Rock journalist] had died. “‘I know’, I said. ‘I’d heard’. And Eddie laughed. ‘I thought I’d better call you in case you go next’, he said.

“I used to speak to Phil [Taylor, former Motörhead drummer] now and then. He’s been ill though. He’s convalescing at his sister’s house now, I’ve heard.”

He returns to the earlier comment from Mikkey, about his stubbornness and emits a low, gravelly, laugh. He said that then, did he?

He did. Does it upset you?

“No. I think that’s all right. Could have been worse. Nothing keeps me awake at night anymore,” he says, “except speed.”

Except it doesn’t, he adds quickly. Speed doesn’t keep him awake at night because he doesn’t take it. Well, not routinely, certainly not in the same quantities he used to. He’s made some small but important adjustments to his rock’n’roll lifestyle.

It’s a well-documented part of rock’n’roll legend that Lemmy used to drink a bottle of Jack Daniel’s a day. Not any more.

“I stopped drinking Jack Daniel’s and Coke because the sugar in the Coke wasn’t good for my diabetes,” he says. He still has a tipple, but he’s moved onto wine. “I don’t drink much,” he says. The fags went last year.

Does he still take speed? “No,” he says, adding cryptically, “not really.”

Can he tour without the booze, fags and drugs? Were they a crutch he relied on?

“They were never a crutch, son,” he says. “I didn’t do all that because I relied on them, I did ’em because I liked ’em.

“I suppose speed was a crutch in the early days, when you’d travelled five hours in the back of a van from one town to another and you needed a blast of something to get you onstage.

“It was a necessity then – but I soon found I quite liked it.”

Back then, all the “little dilettantes”, as he delightfully calls them, were chopping out huge lines of cocaine. Lemmy tried it a few times but never liked it.

“It stuck in the back of my throat and then I found that it affected my hearing. Your ears, nose and throat are all linked. As soon as it started affecting my hearing, that was it.”

Plus, he says, it just made everyone who took it even more self-obsessed and boorish. “You didn’t need that,” he says.

He never took heroin. “It killed my old girlfriend. There was a time when it seemed like I was surrounded by heroin and everyone was doing it.

“But I saw all these people lose their dignity and their money. Why would you do that to yourself?”

He left England more than 20 years ago. At home in LA – and he refers to it as home ,“it’s the only one I’ve got,” he says – he goes to bed late and wakes late, ambling down to the Rainbow Bar & Grill most days, doing rock’n’roll things like “chasing birds above my social station. I catch the odd one but they mainly get away now.”

He doesn’t miss England. He misses the TV and the sense of humour, but the weather is nicer over there and the women wear fewer clothes, he says.

“I miss the England I was born in, but I don’t miss what it is today.”

Why’s that?

“Everything has gone, hasn’t it? It’s fucked. It’s awful.”

Is it? Is it really that bad?

“You know it is. They’re taxing everything, everything is so expensive. It’s shit. The people are the same – it’s the ones in charge.” Arseholes, he says. All of ’em.

The day before the interview takes place, there’s a friendly but nonetheless clear warning from his record company: This is an interview about the new Motörhead record. It’s not an interview about Lemmy’s health.

Well, we can talk about the new album, we say, but it might be hard to fill a nine-page cover story with details of an album we’ve not yet heard, even if it is, in the words of Phil Campbell, an “absolute motherfucker”.

The man himself is a bit more understanding. “I don’t mind you asking about my health,” says Lemmy. “I’ve been poorly. There’s no point lying about it or trying to deny it. I’ve never done that. It’s all part of life’s rich tapestry, isn’t it? I understand you’ve got to ask. And I’m feeling better.”

Can he keep it up though? I tell him what Mikkey said, the question that has loomed over the entire interview: “Isn’t it time, Lem, that you got sick and tired of feeling sick and tired? It’s time you started to take care of yourself.”

“Did he say that?” says Lemmy.

He did, yes. He said he didn’t want it to sound like a direct question, more an expression of genuine concern.

“Ah,” he says. There’s a long pause. I wonder how he’s going to take it. I brace myself for both barrels and a choice expletive.

“Well, that’s all right,” he says, ruefully. “That’s a very thoughtful thing to say. He’s okay, Mikkey. We’re not alike at all. Completely different people. But we have a lot of respect for each other. You need that.”

I wondered how you might take that…

“I don’t mind. And we’ve talked about it. We know things have got to change…”

How do you deal with interviews now, pesky journalists asking impertinent questions?

It depends, he says.

“I don’t mind interviews if the journalist is interested. I’ve done enough interviews where the writer is not bothered, and it’s not a two-way thing – just the journalist working his way through a list of questions. Too many of them don’t listen. They have a script and they stick to it. I don’t like that.”

You get a pretty good press these days though…

“Yeah, it’s come full circle. I remember when the NME said we were the worst band in the world. They said we’d last six months.

“I think the longer you stay around, the more respect you get, even if it’s a begrudging respect. The press we get today makes it hard to justify my attitude sometimes.”

Looking back over those 36 years, what is your proudest moment?

“It changes,” he says. “I remember the first time we sold out the old Marquee. Lines of people down the road, waiting to get in. I was proud of that. Then selling out the Hammersmith Odeon, getting a residency there. Then going abroad, doing well there.

“We went to Argentina a few years ago with The Ramones. I couldn’t see the back of the audience the crowd went back so far, but they were jumping up and down as far as I could see. We’d never been there before. I stood on that stage that day and felt like a lucky man.”

And he is a lucky man, he says. He’s lived a charmed life. “I don’t do regrets,” he says.

“Regrets are pointless. It’s too late for regrets. You’ve already done it, haven’t you? You’ve lived your life. No point wishing you could change it.

“There are a couple of things I might have done differently, but nothing major; nothing that would have made that much of a difference.

“I’m pretty happy with the way things have turned out. I like to think I’ve brought a lot of joy to a lot of people all over the world. I’m true to myself and I’m straight with people.”

Has your illness this year made you more aware of your own mortality?

Not really, he says, bracing himself for the obvious mortality question. He seems to get asked it a lot in interviews these days.

“Death is an inevitability, isn’t it? You become more aware of that when you get to my age. I don’t worry about it. I’m ready for it. When I go, I want to go doing what I do best. If I died tomorrow, I couldn’t complain. It’s been good.”

You know that, when you get to the death and mortality question, the interview is nearing the end. We’ve covered a fair bit of ground here, Lem…

“I think so. Have you got enough?”

I think I have. Is there anything you want to say, a message to the people reading this, perhaps?

“Don’t have any regrets. And don’t die ashamed.”

You won’t die ashamed, will you?

“I fucking won’t,” he says. And that, I sense, is that. The interview draws to a close.

Cheers, I say. Cheers, he says. “I enjoyed that. I’ll see you on the road.”

Right you are, I say. And then he’s gone.

At least I think he’s gone. It turns out he hasn’t. “Whoopsadaisy,” he says.

And there’s laughter. Deep, low, genuine laughter. And then he’s gone.

A DIRTY HALF-DOZEN

Six of the best from Motörhead’s current line-up that you may have missed.

OVERNIGHT SENSATION

(from Overnight Sensation, 1996)

Immediate proof that the latest three-man Motörhead line-up was more than a match for all previous incarnations, Overnight Sensation threw acoustic guitars and a gnarly Lemmy bass-line into the mix, all driven along by that unmistakable grinding gait.

RED RAW

(from Hammered, 2002)

Most people’s perception of Motörhead is based on the heads-down clatter of Ace Of Spades. Red Raw deftly renewed that ageless, relentless, high-speed battery via a dash of brutish post-thrash modernity and lyrics that drip with moonlit murder and madness.

KILLERS

(from Inferno, 2004)

Motörhead’s pop sensibilities have always simmered beneath the surface of their trademark ear-destroying clangour. Killers is as catchily urgent as anything in the band’s vast catalogue: a strident stand-out on one of the strongest albums they’ve done.

WHOREHOUSE BLUES

(from Inferno, 2004)

The blues have always blazed darkly at Motörhead’s creative core. As a result, this stripped-down acoustic paean to lives lived at full force made perfect sense. ‘_Y_ou know we ain’t too good looking,’ sings Lem, ‘but we are satisfied.’ Ditto, sir.

SWORD OF GLORY

(from Kiss Of Death, 2006)

Lemmy’s ability to wring fresh poignancy from the idiocy of war and its mark on history has long been one of Motörhead’s sharpest weapons. Here he bellows his world-weary poetry over pummelling riffs of startling efficacy. Smart and vicious rock’n’roll par excellence.

(from The World Is Yours, 2010)

As menacing and brutal as anything in Motörhead’s armoury, this monstrous highlight from 2010’s widely praised The World Is Yours revisited the filthy, menacing territory of Orgasmatron while reaffirming how utterly obnoxious and heavy this trio of ne’er-do-wells can be at their best.

This was published in Classic Rock issue190

** Order the Fanpack edition of Aftershock **at www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk/motorhead

Get all the info on the 2014 Motorhead UK tour here