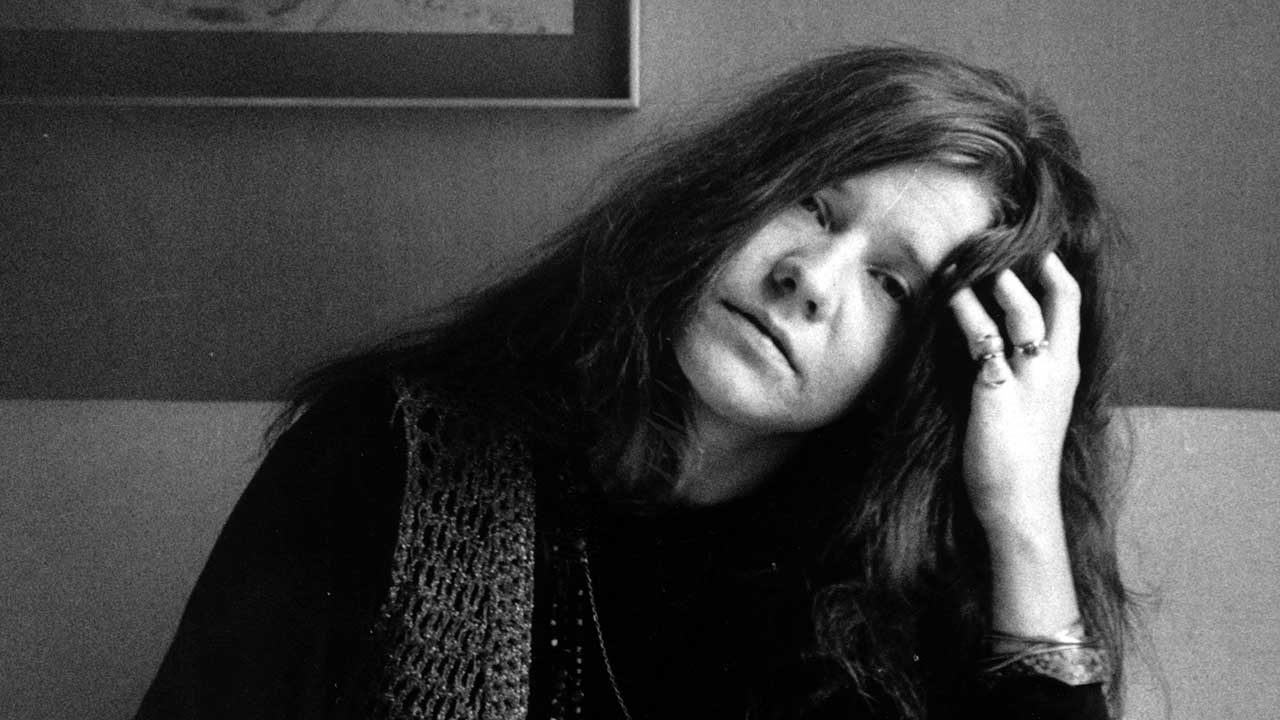

In October 1968, Janis Joplin had a No.1 album, a Top 10 single and a string of sold-out tour dates. One critic raved about her “urgent, blazing white blues” voice. Another said she sounded like “she was calling out from the second-story window of a bordello, inviting you up”. In her first blush of superstardom, the 25-year-old singer of Big Brother & The Holding Company should’ve been riding high. But she was miserable.

Weeks into her group’s tour, supporting their second record Cheap Thrills, with the hit Piece Of My Heart blasting out of radios everywhere, Janis was bored with the increasingly formulaic approach to their live shows. She felt her bandmates were getting lazy. They were all downing different drink and drug cocktails of choice – speed, Seconal, Southern Comfort – which made them edgy with each other offstage. Midway through a European tour, Janis announced that she would leave Big Brother once their dates were fulfilled.

Her restlessness dovetailed with her ambition. The rapturous reception she was getting in the UK and Germany that autumn fed her dreams of international stardom. And whispering encouragement in her ear from the sidelines was manager Albert Grossman, who’d come up through the New York City folk scene, managing Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul & Mary. Once described by a musician as a “pudgy barracuda”, Grossman promised Janis he would land her a deal for two million dollars – if she agreed to go solo.

At the same time, Columbia Records president Clive Davis was wooing Janis with visions of her as a blend of Aretha and Streisand. He wanted brass, strings, Vegas, TV specials, the works. Flattered with the attention, Janis saw it all as a way out of her stagnant situation, and began assembling a new group of musicians.

Once the Columbia deal was inked, Davis was anxious to get her in the studio. Recording began on June 16, 1969 in Columbia Records Studio in New York. Grossman chose Gabriel Mekler to produce.

Best-known for helming Steppenwolf biker-themed hits Born To Be Wild and Magic Carpet Ride, the classically-trained Mekler was opinionated and strong-willed. He didn’t like Janis’s choice of musicians for her band. They fought back and forth to a compromise, but Mekler sulked through the sessions and would ignore the suggestions of the players he didn’t choose.

Davis’s haste to get her solo debut out in time to capitalise on the success of Cheap Thrills also meant the new band didn’t have enough time to gel as a unit. While the large cast nodded to the way records were made at Stax and Motown, the flip side was that the band never transcended the feeling of being hired hands. Once again, drugs and egos reared their ugly heads. And 1969 was the year of heroin.

Guitarist Sam Andrew, a holdover from Big Brother, said, “Too many of the musicians were buying balloons [of heroin] rather than concentrating on the music.” Saxophonist Snooky Flowers added: “We were musicians and we knew how to play. We weren’t just a bunch of hippies running around playing three chords.” He thought Janis was intimidated because she realised the band was “musically beyond her”.

In this chaos, Janis got a bit lost on her own album, personally and musically. Her father Seth later said: “The brass in the group didn’t suit her. Her voice was an orchestra in itself.” And yet, testament to her otherworldly talent, there are sublime moments on Dem Kozmic Blues. The best of them have spare arrangements that bring her vocals to the forefront. There’s Maybe, a creative reimagining of an old girl group hit, and One Good Man, where she spars with Michael Bloomfield’s lean, fiery guitar licks, making the track sound like a blueprint for the first two Led Zeppelin albums.

But the standout is a cover of Rodgers & Hart’s Little Girl Blue, from the 1935 Broadway show Jumbo. Though she tweaks Lorenz Hart’s lyrics, there is a deep empathy in the track. Hart, like Janis, was an outsider, uncomfortable in his own skin, perpetually insecure, given to jags of depression and drinking.

Though she may not have known that, Janis found a cross-generational kindred spirit and it brought out all the colours in her voice. No other performance better illustrates her extraordinary openheartedness, empathy, and ability to cry for herself while crying for us as listeners.

Released in September 1969, the album went gold, but yielded no Top 10 singles and a mixed reaction from the press. A typical review, in Rolling Stone, raved about Janis’s singing but faulted the accompaniment as “lumpier than a beer hall accordion band”. She hit the road with many of the same musicians and had uneven gigs.

“They didn’t get me off,” she said. “I have to have the umph. I’ve got to feel it, because if it’s not getting through to me, the audience sure as hell aren’t going to feel it either.”

By summer 1970, she’d hired a new band, The Full Tilt Boogie, that she called “so heavy you can lean on it”. But before her creative evolution could continue, Janis was gone. A year after her death at 27, Columbia released Pearl, the last piece of a puzzle that will remain forever unfinished.