It’s the way he tells them. You might be interviewing Walter Trout in the coffee lounge of a Holiday Inn, or over a shaky Skype connection on a wet Tuesday, but when the veteran bandleader fires up an anecdote, rewinding to a pivotal scene in his own toe-curling biopic, he takes you along for the ride.

Squalid 70s drug-dens. Murderous LA biker clubhouses. Clammy backstage orgies. You’re right there with him, watching through your fingers.

Right now, The Blues is riding shotgun as Trout slips through another wormhole in the space-time continuum. The date is October 31, 1974, and the New Jersey bluesman has just arrived in California to seek his fortune. “I’d driven three thousand miles across the country in my VW Bug, camping in a pup tent, living on peanut butter and jelly,” he begins. “When I got into Costa Mesa, my buddies were all going to a Halloween party. Well, I didn’t have a costume, but they tell me they have this full-body gorilla suit that nobody is gonna wear. I figured, what the hell, y’know?

“So I put this gorilla suit on, with nothing underneath, then we all took a hit of LSD and we drove off to this Halloween party. Now, I had only been in California for five hours at this point. So I’m at this party and I start having what you’d call the quintessential bum trip. I’m thinking, ‘I’ve made a big mistake. I gotta get in my car right now and drive back to Jersey.’ I get more and more despondent until finally I just leave the party and start walking.”

The punchline: “At which point, I realise I’m completely lost. I don’t know where my friend’s house is, or how to get back to the party. I have no money and I’m peaking on LSD. I came across this hamburger place called Bob’s Big Boy. I walked in, sat down, took the gorilla head off, set it down on the counter and broke into sobbing uncontrollably. I told the waitress: ‘I just got here, I’m on acid, I’m in a gorilla suit, I don’t know where I am and I’m freaking out.’ So she got me a cup of coffee and drew me a map. Turned out it was actually very easy; there were only two turns to make. So I walked back, in my suit, people pulling up next to me and yelling out of their cars. All I could think of the next day was, hopefully it’s gonna be uphill from here…”

If you had kerb-crawled the tragic figure pounding the highway that night in 1974, it’s unlikely you’d have bet on Trout surviving a month in the meat-grinder of the LA music industry, let alone toasting his 25th anniversary as a solo artist, as he does in 2014. The band leader’s record label, Mascot, has certainly pushed the boat out, marking the quarter-century milestone with a fistful of commemorative releases, including reissues of 10 classic albums on premium 180-gram vinyl and a documentary directed by Frank Duijnisveld.

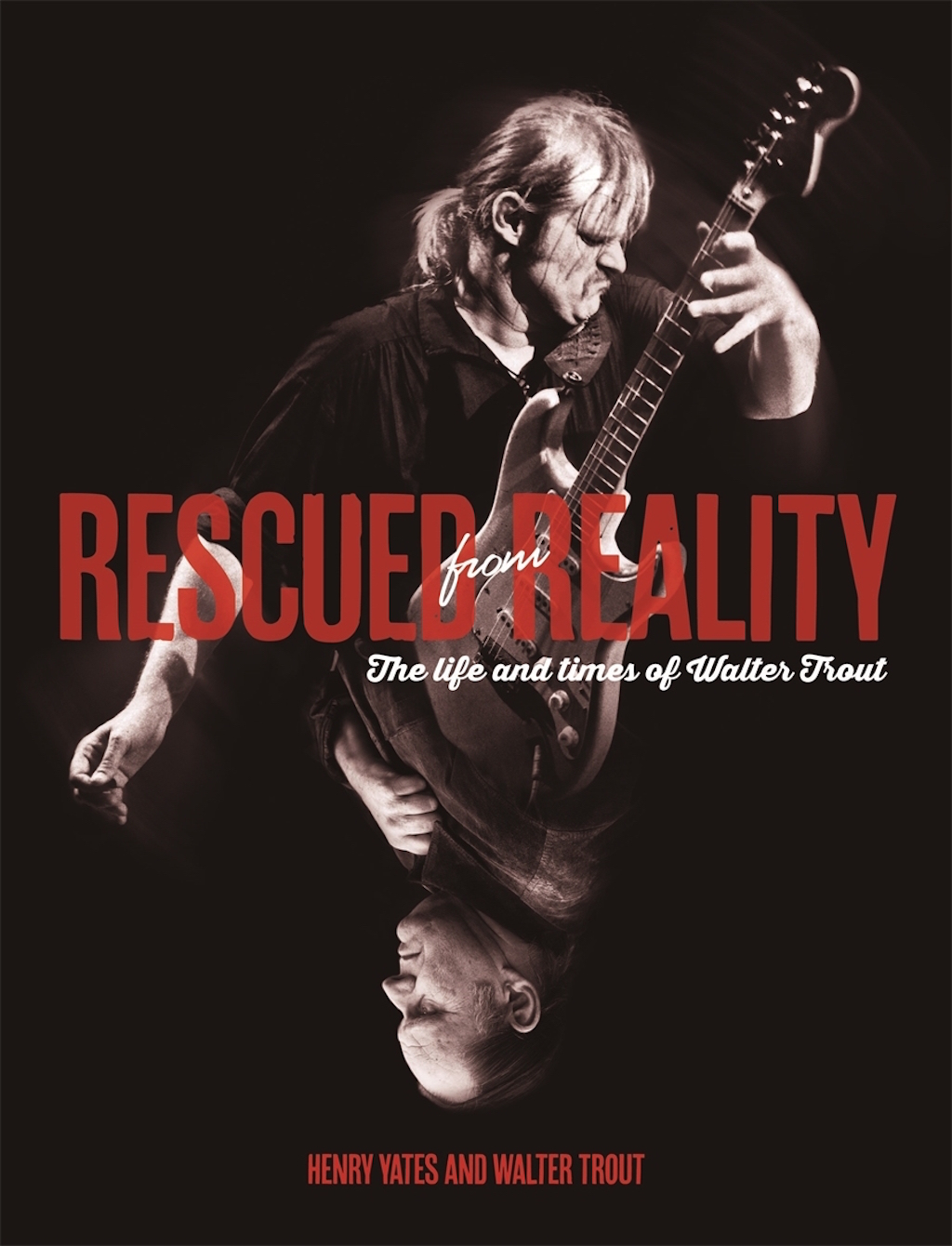

There’s also Rescued From Reality: the official biography due next month, co-written by Trout and myself during a flurry of Skype interviews and one marathon face-to-face session in Cardiff. In the anecdote stakes, the gorilla suit is in pretty good company. There are bust-ups with Bruce Springsteen, Ike Turner and Albert King (“Albert tells me, ‘The backstage toilet is for the headliner – get the fuck out of here!’”). There are death threats from Canned Heat’s biker-gang management (“This large biker fellow tells us, ‘I’m gonna personally murder each and every one of you!’”). Beatings from Buddy Rich. Dope-deals gone bad. Vagrancy. Cavity searches. In one particularly low ebb, Trout cooks up freebase in his own underpants. Without fear of arrogance – because it’s his story, not mine – it makes Mötley Crüe’s The Dirt look like The Gruffalo.

My own favourite episode finds the guitarist and his solo-period bassist Jimmy Trapp [who passed away in 2005] marooned in Ketchum, Idaho, circa 1977, having been blown out on a club residency. Without money or transport back to Cali, the pair are reduced to sleeping in cages at a local dog kennels. “These cages are three feet wide, maybe three feet tall,” Trout reminds The Blues, “so you have to crawl in on your hands and knees. You’re laying on concrete, surrounded by dogs, and they’re barking and shitting all night. It was horrible. One night, after getting sick of all this, me and Jimmy went walking down the main drag of Ketchum, the yellow line between us, drinking a bottle of Jack, tripping on acid and swearing that we’re not gonna let this get us down and we’re gonna do something with music. When my wife read that part back to me, I just fell apart, because it brought back memories of my good buddy Jimmy, y’know?”

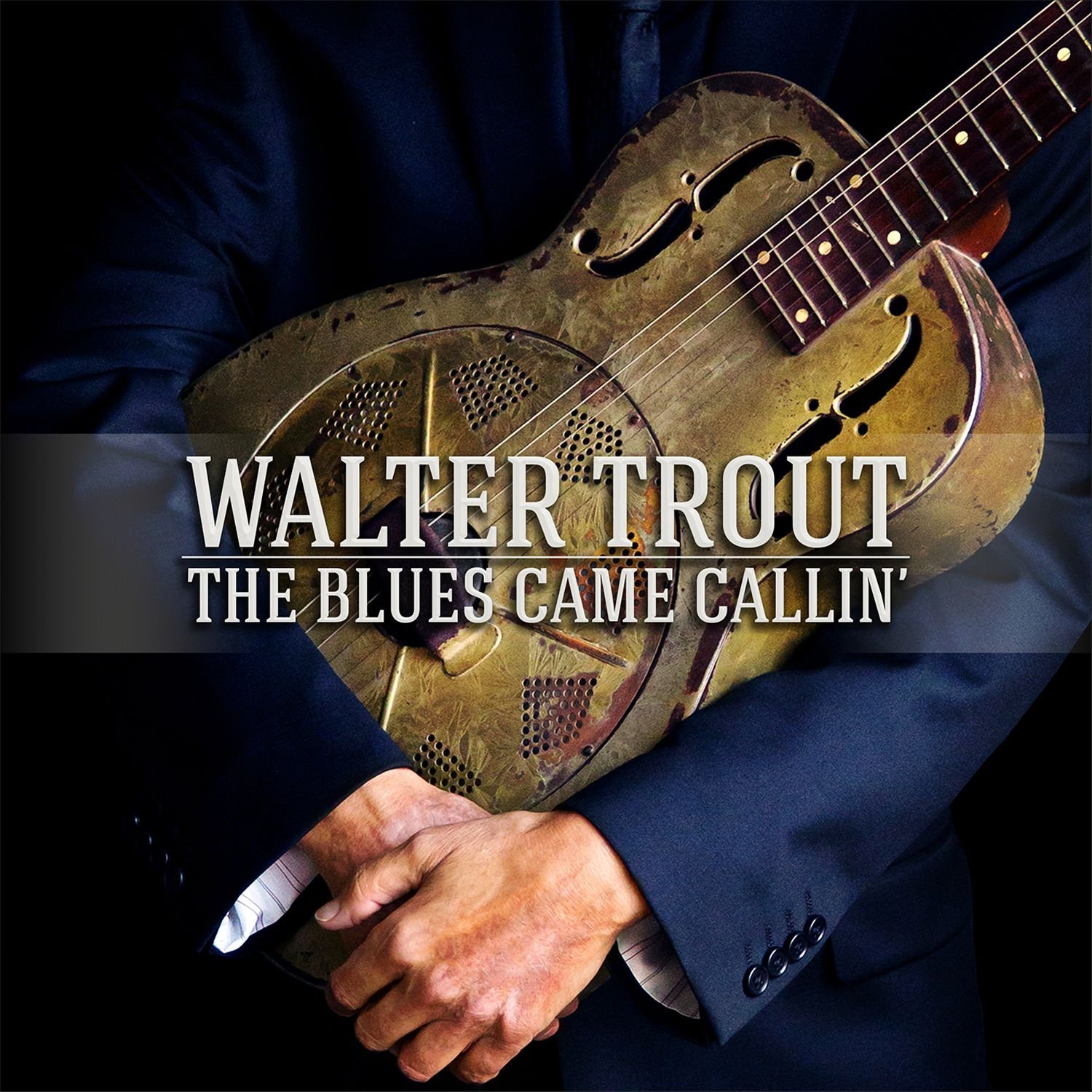

But enough of the sales pitch. For most fans, the pivotal release of Trout’s anniversary year is The Blues Came Callin’. When sessions for this latest studio album began, back in April 2013, the guitarist had no particular concept or lyrical thread; he simply wanted to turn out another dazzling slab of blues-rock to maintain the velocity of 2012’s Blues For The Modern Daze. Since then, life has changed beyond recognition, and the record’s guiding theme alongside it. “I can’t write bullshit,” Trout shrugs, eyeing me steadily down the webcam from his home in California. “I have to be honest about what’s going on. So this record became a whole different thing. There are songs on there that look square in the face at what’s been happening to me.”

Most of our readers will hardly need reminding what that is. If you’ve taken even a cursory interest in blues-scene current affairs over the past nine months, you’ll know this album arrives on the heels of the bluesman’s darkest days, and that the 25th anniversary hoopla has suffered a desperate change to the script. “I wish the liver would have waited,” Trout laughs, a little darkly. “Because I had this big year planned, with all these big tours, this and that…”

It all began last June. On tour in Germany, the guitarist awoke one night in his hotel room to find his legs bloated with fluid and “looking like telephone poles”. He didn’t panic, yet.

“It was obvious that something was up, but at that time, I had been getting some cramps, so I’d bought some magnesium pills. And being the guy I am in the book, where if one pill is good then 10 is better, I started mega-dosing on those. So when I woke up that night, I figured it was just a magnesium overdose. It was only when I got home that I found out it was cirrhosis of the liver.”

When The Blues speaks to Trout in mid-March, despite experiencing drastic weight loss, huge discomfort and sporadic trips to hospital, it seems medication could halt the spread of cirrhosis. “I’m having some rough side effects,” he tells us. “I don’t think I’ve had a real night’s sleep in months now. I lie in bed at night and my hand is flapping through the air and shit. It’s completely out of my control. Just a few days ago, my wife Marie had to spoon-feed me. That, again, is a side effect from this drug that I’m on, and when it happens, I can’t get the fork up to my mouth because my hand is shaking. It makes me itchy, too. And there’s mood swings. When there’s a commercial for McDonalds and they show a Big Mac and you start weeping, you know you’re on the emotional edge.”

Shortly after our interview, however, Trout’s liver will fail, sending him into the intensive care unit at UCLA, where the diagnosis emerges in late-March that without a transplant he will not live beyond 90 days. An online fundraiser to pay his medical bills (organised by the family of Trout protégé Danny Bryant) blitzed its target of $125,000 in days and underlined the worldwide devotion the great man inspires, but as this issue of The Blues went to press, the agonising wait for a donor continues.

Right now, events are moving so fast that print media can’t hope to keep up. All we can do is write this feature in the present tense, and pray this perennial survivor beats the odds, just as he has so many times before. “As evidenced by some of the stories in the book, I should have been dead years ago,” admits Trout. “Y’know, I should have been dead when I was running around shooting heroin in the 70s with Jesse Ed Davis. I came so close to OD’ing on heroin and cocaine, many times. There were many times I’d take so much cocaine I was close to a heart attack. I feel like I was given a second chance back then. Then, with the drinking, a third chance. Just chance after chance. Now I gotta fight, and maybe I’ll be given the next chance.”

It’s worth touching on the roots of Trout’s alcoholism, if only to silence the pockets of chatroom trolls who have suggested that, as a hellraiser until the late-80s, he brought his liver troubles on himself. His stepfather was an alcoholic, he reminds The Blues today, whose mental health issues made for a deeply disturbed adolescence in New Jersey.

“I remember, one time, he chopped the bedroom door down with an axe, and my older brother had to hold him off with a shotgun. That was terror like I’ve never known. Even though my brother had a shotgun, his hands were shaking, because this guy was a six-foot-six ex-marine, and at the time my brother was only 15 or 16. We were both fucking terrified. It’s hard to even describe it.”

Alcohol, when it entered the frame, was never a hedonistic pleasure, but the best way for Trout to soften the trauma of those days. “I remember the first time I ever got drunk, and it wasn’t fun,” he says. “I was 15. After we had jammed, me and my friend, his parents went out and we got into their whisky cabinet. I ended up puking my guts out, coming home and puking all over the apartment, my mother running around after me with a bucket, cleaning up. It was horrible, actually. And there was a good period of time, between that experience and what I had seen the booze do to my stepfather, where I swore I would never drink. That fell by the wayside.”

And how. “There was a good 10-year run,” calculates Trout. “I was doing a lot of drinking in Canned Heat and in the early days with John Mayall. You know the Chateau Hibiscus story [each night Trout and Mayall would collect half-finished drinks from the venue in a wine bottle labelled Chateau Hibiscus]. But along with the drinking went everything else. The one thing I did do was to get off the heroin in ’77, and I’ve never done it again. So I guess I thought, y’know, I could drink and take cocaine until I’m half-dead, but at least I’m not on heroin. That was sort of the weird way I thought about things.”

What would be a typical daily intake in the Bluesbreakers?

“Oh, I don’t know. A fifth of Jack. When I first got in the Bluesbreakers, on the rider was a fifth of Jack Daniel’s. Coco Montoya and I ended up having to amend that so that we each got our own fifth every night, because a fifth between the two of us was not enough. I mean, Coco even had a flight case for his guitar that had a cut-out for a fifth of Jack.

“I’d drink anything. It didn’t matter. I didn’t drink for taste. I drank to get fucked-up. All these ads about how good this or that liquor tastes? I think it all tastes like lighter fluid, and the reason you drink it is to get a buzz. I mean, who actually thinks whisky tastes good? It’s like drinking rancid piss, even when it’s the expensive kind. So I was not into it to savour the bouquet and all that bullshit. I wanted to get high, and I wanted to get high real quick. My alcohol consumption probably would have killed a horse, but I built up to it. Jimmy was the only one who could keep up, and I actually had a hard time keeping up with him. Jimmy was definitely leading the forefront, and I was his devoted disciple in the drinking world. We were the trailblazers, but he’s dead now.”

Did you like yourself when you were drinking? “Hell, no. Not at all. I didn’t like myself for years.”

Trout stopped everything for good on July 9, 1987. Given that, it seems massively unfair that his old habits should take their revenge now, but the guitarist has never shown a drop of self-pity in his interviews with me, vowing to fight on and keen to push ahead with release plans for The Blues Came Callin’. Patently, this is an album of which he’s hugely proud, despite the bleak context that drove it. “I think the arts quite often work like that,” he considers. “I went to this Beethoven exhibit that’s in a museum out here in the States. They actually have this lock of his hair, and they did this DNA test on it, and they found out that this guy, not only is he deaf, but he’s also got hepatitis, he’s got cirrhosis of the liver, he’s got kidney stones. Just imagine the pain the guy is in. Then he writes the Ninth Symphony. I mean, how the hell do you figure that out?”

The blues works that way too, we suggest. Beautiful music born of terrible times. Trout nods: “Those early blues guys had incredible lives, and that was one of the things that attracted me in the beginning. Y’know, the honesty, and the fact it seemed to me that the bluesmen were not concerned with demographics or buying trends or trying to put out the latest single or get airplay. They didn’t give a shit about any of that. It was, ‘I just want to play.’ It was pure therapeutic music, those guys were doing. It was strictly to get it off their chest and to have some sort of release for that pent-up stuff.”

The Blues Came Callin’ has a similar sense of catharsis. But getting this material down wasn’t easy, stresses Trout. “When I started this record back in April, I was still in good shape, liver-wise. Then my health fell apart over the summer. Every other CD I’ve done, I’ll go in the studio and two weeks later, it’s done. I bump ’em out in two weeks. Write them and record them. Not this one. It’s been almost a year. There were many days that I would be sick and I would drive an hour-and-a-half to LA. I’d do about two hours in the studio then say, ‘I can’t do any more’, turn around and drive home.

“I didn’t want to play it half-assed. For me, it’s gotta have the energy and it’s gotta have the commitment, and as soon as I would feel like that was leaving and I was just going through the motions, I’d say, ‘I gotta go.’ That was frustrating. Very much so. I probably spent more time on the freeways than I actually spent in the studio.

“There were a few times I had to cancel sessions because I went in the hospital,” he adds. “That happened a few times. It was day by day. One time, I almost died, because I had incredibly high potassium levels and incredibly low sodium levels, and they figured out that my brain was swelling and I was hours away from having a seizure. I ended up spending five days in the hospital with IVs pumping shit into me. I had sessions booked, but I had to say ‘No, sorry, I can’t come up and play the guitar or I’m gonna die.’ Thank God for the studio owners, and thank God for [producer] Eric Corne, who worked with me and gave me that leeway.”

They got there. The Blues Came Callin’ will be released on June 2, and as Hugh Fielder’s review affirms elsewhere in this issue, it’s an absolute belter, albeit one that’s frequently painful to listen to. “I’ve been waiting for somebody to hear it and give me some feedback,” says Trout. “It’s almost like you’ve given birth and you’re waiting for somebody to say that your kid is nice-looking. Some of the songs on there are, to me, somewhat gut-wrenching lyrically. But I had to be honest. Y’know, there were times I’d read the lyrics to Marie and she’d go, ‘You want to put that out there?’ and I’d go, ‘Yeah.’ So she was way behind me on writing what I feel and what I’m going through. She knows that the music is therapeutic for me, and that I needed to do that.”

It’s not quite accurate to call The Blues Came Callin’ a one-theme album. On Take A Little Time, for instance, Trout bemoans the frantic pace of modern LA life over a fabulous 50s rock‘n’roll bedrock, while Willie takes a swipe at the various managers to have double-crossed him over the years. “I was ripe for the picking,” he says of the latter. “All I wanted to do was play guitar, sing, write. I had no business acumen. I trusted everybody. All those guys that ripped me off, I thought were my friends. It was never the old cigar-smoking bald guy saying, ‘I’m gonna make a star outta you, kid.’ It wasn’t that shit. They were all my peers, and they came off like they wanted to help me further my career, when in actuality, they just wanted to bleed me.”

Yet there’s no mistaking the thematic backbone that runs through this album. Musically and lyrically, opening track Wastin’ Away sets the tone and the standard, fusing a Zep-worthy rock riff to Trout’s ruminations on the face in the mirror, having lost almost half his body weight. “This album is a raw blues-rock record,” he explains. “There are no gimmicks. I didn’t want to throw in clever little breaks here and there. It’s straight-ahead. With Blues For The Modern Daze, we had all the songs ready to go. But with this album, I’d be driving to the studio, thinking ‘What the hell am I going to record?’ I’ve got a little recorder on my phone, and I started singing the riff to Wastin’ Away. Lyrically, that song was painful to write, but it was also very therapeutic. Music has always been a way for me to exorcise the demons.”

Are you conscious of how much you’ve changed physically?

“Oh yeah. I’m very conscious of it. I mean, it’s unbelievable. I’m skin and bones. I can feel bones in my shoulders and back that I didn’t even know existed on the human body. Y’know, I can feel every joint. It’s kinda amazing. It’s almost like an anatomy lesson. I’m fighting it all the time. I just did 20 minutes on the recumbent bike.”

You genuinely can’t hear Trout’s frailty in the guitar playing on this album: it’s every bit as searing and soul-drenched as we’ve come to expect. The vocal is another matter. At times, it’s audibly parched and strained, but arguably all the more powerful for it. “Part of that is because it can be hard to get air,” he explains, “but it’s also that the diuretics they’ve had me on sorta dried out my throat. So when you hear me talking, my voice is different, and I can’t really put my finger on why, but with some of those vocals, it was very difficult to get anything to come out at all. Y’know, I really had to push.

“At first, when I heard it back, I’d be sorta shocked. Then I’d think, ‘It is what it is.’ This is where I’m at right now in my life. This is what I’m able to do. I hope my fans out there who get this record will enjoy it, even though my voice on the Luther album sounds so different: big, full and boisterous, with a lot of vibrato and range. I don’t have any of that right now. But I did my best to sing it like I mean it. And I think it gives it a little extra urgency, because I’m working so hard to get it to come out. It used to just be so simple…”

Scan through the lyric sheet and you’ll find several lines that suggest Trout is fearful that his powers are fading. “To me,” he says, “another of the most important songs on this record is the title track, The Blues Came Callin’. It didn’t start like that, lyrically. At first, it was just gonna be a regular old blues song but, after what happened to me, I went back, changed the lyrics and resang it. That one is really gut-wrenching, but it’s how I feel. There’s a grand tradition of personifying the blues. Y’know, like Buddy Guy has an old song called First Time I Met The Blues. That’s sorta what I tried to do.

“So that song is about me laying in bed, having this realisation that my whole life is changed and it won’t ever be the same. I could get my health back, get a transplant and be doing good, but I’ll never be the same guy. Even if I get optimum health, I’ll never be the same guy up here.”

Musically, at least, that title track brings back happy memories, with Trout calling on the Hammond skills of his one-time employer, John Mayall. “I said to John, ‘You know what? I’d love to hear you play B3. You played it on the Beano album, but ever since then, the whole time I was with you, you used this shitty little synthesiser that sounds real cheesy.’ John said, ‘I don’t know if I remember how.’ But he went out and played for about five seconds, then we recorded that song. It was live, one-take, no discussion.”

There’s also Mayall’s Piano Boogie, which does what it says on the tin. “Recording that was a blast, man,” remembers Trout. “With that one, I said to him, ‘John, I want you to do something else that you’ve not done on record for a long time. I’ve heard you play boogie-woogie piano, and I think you’re really good at it, but the last time you recorded a boogie-woogie song was in 1970.’ They have this beautiful Steinway piano in this studio and John just walked over and started playing it. I looked over at Eric, and Eric ran over and hit the record button, and the rest of us just kinda stumbled into the studio and joined in. John didn’t even say, ‘Okay, are we ready?’ He just went for it. Like, ‘you’d better get this now, because here it is.’ It kinda cracked me up. We had to figure out what key he was in.”

Mayall was your rock and confidant in the depths of the drinking years. Has he given you any advice in your current situation?

“Not really. At the Classic Rock Awards in November, he did really take of me. He and Marie shepherded me around. He was very concerned for me – I could tell – but he also had some points to make. There was one part where there was a long flight of stairs we had to go up, and John’s like, ‘Do you want to take the elevator?’ I said, ‘John, I’m gonna try these stairs.’ So he got in front of me – 80 years old – and he sprinted up this long flight of stairs, three at a time. He got up to the top, folded his arms, stood there and waited for me, because I’d take about five steps and have to stop and breathe. But he was just looking at me, like, ‘Boy, you have fucked yourself up, Walter…’”

More metaphorically, the long climb back to health is a theme explored on perhaps the album’s best track, The Bottom Of The River. “That’s probably one of the songs I’m most proud of in my life, lyrically,” says Trout. “That’s a song about hitting the bottom. And hitting the bottom is easy. It’s getting your way back up that’s difficult. The guy in the song falls in the river. He gets pulled to the bottom. The current drags him and holds him. So he has to make the decision that he’s going to fight and that he’s going to live. This guy, he has to summon all the strength that’s in him. He doesn’t think he has the strength to make it. But then he realises what he has to live for. He sees his life, and he realises that he wants more. He finds the strength, fights with everything he has and gets back to the surface.

“And at that point, he looks around and he sees beauty in the world he never saw before, or he took for granted. I go through that, too, every day. We have a lot of crows around here, and I have this beautiful little back patio, right in the sun. It’s quiet and you can sit out there and hear the waves break. I used to go out there, but then these crows would get on the trellis above me and start screaming at each other, in crow talk. They’re all pissed off, right? Before, I’d be like, ‘Hey, you’re disturbing my peace!’ and I’d start yelling at them. Now, when they come and they start doing that, I think it’s the most beautiful thing I ever heard in my life. I just have a different view of things.”

Trout will tell you all about his renewed appreciation: for nature, for mankind, for life. Music, above all, has never sounded sweeter to him than it does right now, nor provided a more tangible lifeline. It’s truly heartening to see his eyes sparkle when he recalls the creation of this new album, or reflects on the shows of late 2013, when the energy from the audience visibly eased his condition. Alongside the love of his family, it’s music that has made these times bearable, and God willing, it’s music that will be waiting for him when he returns to health.

“Music lifts me,” Trout agrees. “It nourishes my heart and soul. It gives me purpose. My wife and children are obviously a huge purpose, but to keep making music that might mean something to somebody… y’know, it puts me back in touch with the reason that I’m here.”

_The Blues Came Callin’ is out now on Mascot (Special Edition includes documentary). Rescued From Reality: The Life And Times Of Walter Trout by Henry Yates and Walter Trout is also out now. The Vinyl Collectable Series is released throughout 2014. _

‘WALTER TOLD ME TO GET MY SHIT STRAIGHT.’

Mike Zito writes movingly on the man he calls ‘my hero, my mentor, my friend’.

“Walter Trout is going to die.” That’s the news I got a month ago, if he doesn’t get a liver transplant soon. I knew my friend was not doing well, he’d been losing weight over the past year and was not looking as healthy as he once was, but I just spoke with him a month or so ago and he was cracking jokes and being a wise ass. He told me he felt great, but his liver was really giving him a hard time. I guess I assumed he would get better, not worse. It was heartbreaking to see the thin-skinned, boney pictures of Walter on Facebook.

Walter Trout is my hero, he is my mentor, he is my friend. I have looked up to him for so long and suddenly he is in the wake of pain and suffering. I opened for Walter in St Louis for the first time in 1999 at Mississippi Nights. He told me I was good and I could open for him anytime. That was a huge shot to my ego. A few years later I showed up to open my sixth or seventh show with Walter and was really messed up on drugs and gave a poor performance. Walter sat me down after the show and chastised me. He told me exactly what Carlos Santana had told him years ago with John Mayall: “You’re wasting your talent.”

Walter told me I had a responsibility to the music, the fans and my family to get my shit straight and play the music honestly and from the heart. Walter was one of the first friends I called when I cleaned up and he told me he was there for me night or day. Walter Trout is a rebel, a maverick.

What I, and the legions of his adoring fans, hear is honesty. He is a poet. He sings from his soul, songs of love for his wife, hope for his children, and stands up for the common man. Walter Trout has purpose. His music speaks volumes. Walter puts more emotion into one note than most put into an entire album.

REALITY BITES

The Blues grills Henry Yates, the author of Walter Trout’s white-knuckle biography.

So what’s Walter really like?

I must have interviewed more than a thousand musicians, and I’ve never met anyone cooler, wittier, kinder or more charismatic than Walter. He’s like a stand-up comedian spliced with a philosopher: one minute he’s telling you a filthy joke, the next he’s discussing the endgame of the American Civil War. He’s seriously intelligent and well-read but equally bawdy and irreverent. I can see why all the young bluesmen worship him. He’d have made a great teacher, but I’m glad he chose music.

What were the challenges of writing Rescued From Reality?

Certain areas of Walter’s life are desperately traumatic, and I knew those sessions would hurt. Walter broke down several times – particularly when recalling the violence of his childhood – but he always picked himself up and carried on. The biggest challenge was when his illness set in. It’s hugely poignant to write someone’s life story when their life is in jeopardy. Like the warhorse he is, Walter kept going, fitting sessions around hospital treatment. His amazing wife, Marie, told me he found the book a welcome distraction – it meant a lot to hear that.

**How did the process work? **

Like all the best rock stars, Walter gets up late: his body-clock is always on touring time. So he’d generally Skype me at noon, California time, and we’d go for an hour each time. We also met up in Cardiff for an all-day session last May, just before his health problems began. Interviews with musicians can be like pulling teeth, but once Walter trusts you, he gives you the kind of solid-gold material that us hacks dream of.

What’s your favourite Trout anecdote?

How Walter dodged the Vietnam war by taking a daily hit of LSD and refusing to wash for a fortnight before his appointment at the draft board. But it’s hard to choose a favourite. Walter has lived the kind of swashbuckling, death-dicing, hell-and-back existence that beggars belief. I’m just surprised nobody has written this book before.