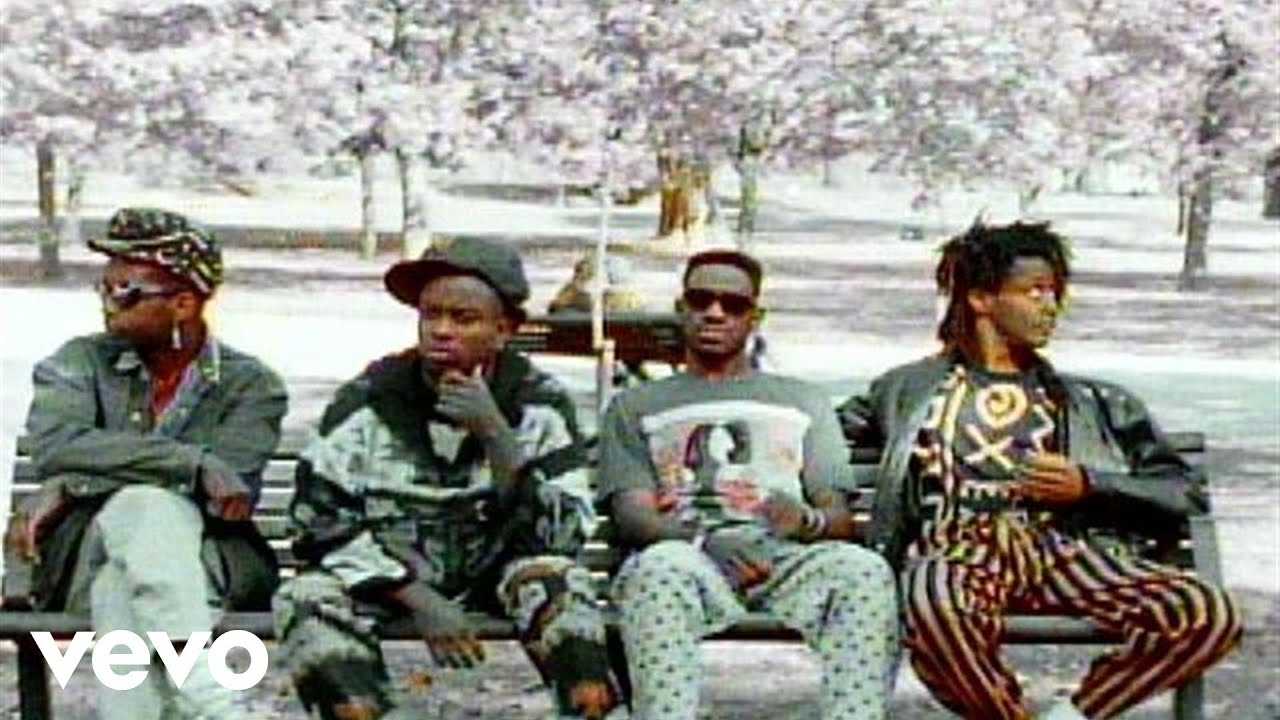

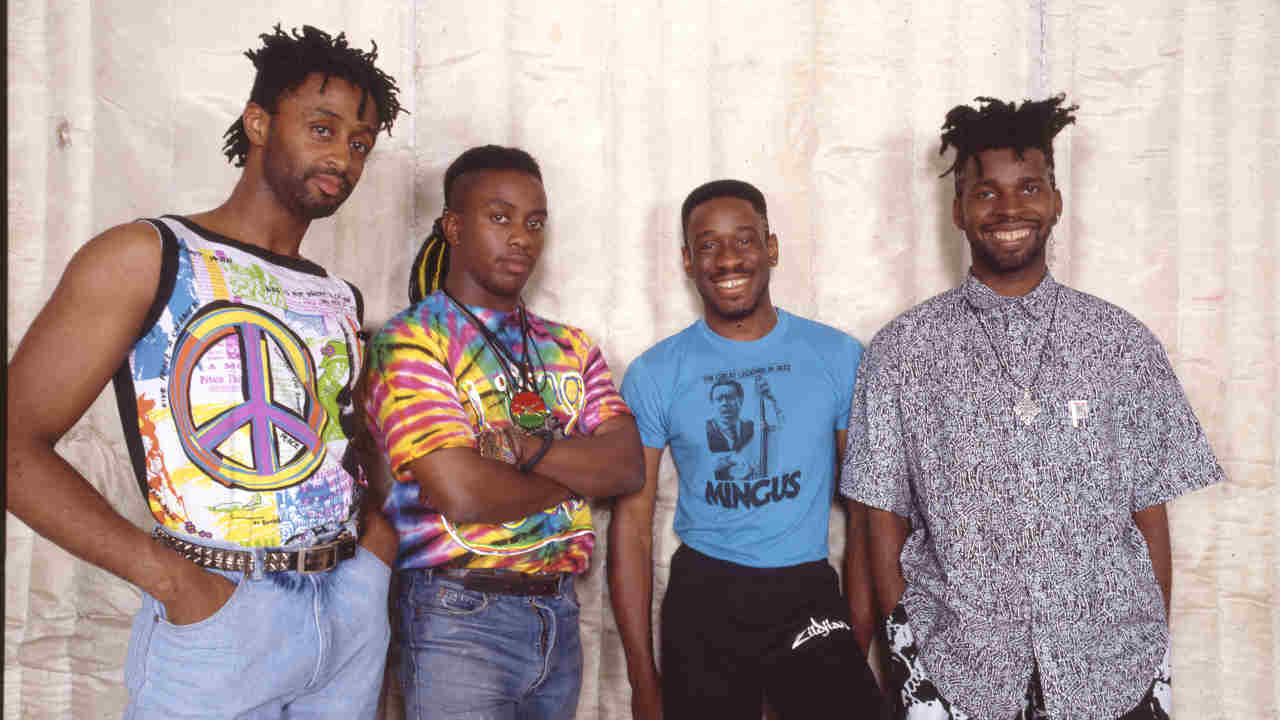

Founded by guitarist Vernon Reid, a member of New York’s groundbreaking Black Rock Coalition, Living Colour were one of the most revolutionary rock bands of the late 80s. They notched up hit singles Cult Of Personality and Open Letter (To A Landlord) and acclaimed albums Vivid, Time’s Up and Stain before imploding. Classic Rock met the recently reunited band in 2003 on the eve of their comeback album, Collideøscope, to look back over a trailblazing career.

The lush green of the sodden Austrian Hills is so dense that it strains your eyes to look at it too long. It’s softened by the occasional heavy strands of white cloud and intermittent sheets of black rain that whip the flags in the hotel car park into a punchy tattoo. The overall effect is a dewy saturation that makes you think the colour is going to drain out of the landscape. It’s been raining here since both Classic Rock and Living Colour arrived.

Late last night at the Saalfelden Jazz Festival (‘Three days of deep impacted jazz, side shows, club, short cuts and Alpine vibes,’ trumpets the event poster) Living Colour roused a demonstratively demure and introspective jazz audience to its feet. Pushed back to a 1am start by the late inclusion of the inventive if somewhat histrionic three-piece Kroyt – keening female vocals twinned with a deeply serious and erratic guitarist who chose to stare down each member of the audience individually – Living Colour enlivened a sell-out crowd beneath the huge, white marquee, from a state of sedate politeness to an invigorated rabble resplendent in brightly coloured pullovers. Still a good month from release, the songs from their new album Collideøscope were met with an enthusiasm that only an audience who have spent the day watching artists play in 13/8 time could possibly muster. The crowd, a generous seven or eight thousand, danced and frugged as erratically as the intricate rhythms they’d enjoyed all day – possibly belying how they dance at home when the house is empty…

“Man, what a day,” says Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid the next morning, joining me briefly on the steps of the hotel as I take in the mountains and squalls of rain. “Shall we start?”

Reid formed the first version of Living Colour – then a trio – around 1983. Ten years later they would release their third studio album, Stain. Two years after that it was followed by the Pride best of; not too much later a pithy and rather prissy statement arrived from Reid announcing his decision to quit the band.

Even though they’ve lived in the public consciousness since the Cult Of Personality single hit at the tail end of 1988, Collideøscope will be only the band’s fourth album proper. It says much for their new record and the band’s initial grace and endeavour that either end of their catalogue remains poised timelessly above trend or market forces. Their debut, Vivid, was remastered and reissued in 2002. Played back to back with Collideøscope, the two albums act as impressive musical bookends for a band who confronted stereotypes, social norms and a daily, almost indifferent kind of racism that cast a near-invisible pall – invisible to those not affected by it – across their lives.

Shoehorning them into a moral corner may have done them more harm than good in the long run, when a hook-hungry media began to cast them more as social observers than as a sentient rock band. Given that and the fact that in interviews they did around the time of Stain they sounded as though they were stepping down from the soapbox they had erected – they constantly insisted on a more human, less political slant to the album – it’s refreshing to hear vocalist Corey Glover refusing to shy away from the pointed stance the band has again adopted with their latest album.

“We’ve seen a lot of things go down that aren’t being addressed, and someone needs to talk about that,” Corey says, as Vernon nods, a pot of tea poised above his cup. “We had an obligation then and we have an obligation now to speak the truth, and we’re never going to be afraid of that.”

The three of us are seated in the hotel bar. Mountains rise up either side, their peaks obscured by a sky that threatens to keep on falling. “We didn’t want to make a record for the sake of making a record,” Corey continues. “We were never about that, ever. But it had to have a theme; it had to have something to say. We laboured over that idea for a long time, because we would write songs that came out of the creative process but they didn’t feel like they were thematically worked – ‘what is the genesis?’ you know? We tried really hard for it to mean something; we didn’t just want to make a record that said hey, we’re back. That’s not enough.”

“So now we’re trying to figure who each person is. On a level we’re still the same people… the same guys,” Vernon says, with an elongated pause. “But there’s another part of it in figuring out how could we be together, what do we have to say? That’s been a nagging question.”

As history has it, Vernon first heard Corey singing when he saw him perform Happy Birthday at a friend’s party. Vernon had already played with jazz drummer Ronald Jackson in his Decoding Society band, and the guitarist’s dazzling and eclectic reputation had already earned him gigs with artists as diverse as pop producer Kashif and the erratic and tough-sounding jazz/dance outfit Defunkt. But it wasn’t until 1986 that the line-up of Corey, Vernon, drummer Will Calhoun and bassist Muzz Skillings began to make a name for themselves in New York. Regulars – to the point of being something akin to the house band – at CBGB’s, one night Living Colour’s reputation in the city and a confluence of voices in one rock star’s ear saw Mick Jagger going to the club to see them play.

“What was that, 1987?” Vernon asks. “I knew he was there, and I didn’t tell anyone in the band. One of our managers at the time said that Mick Jagger and Jeff Beck are here. And I said, okay, and I didn’t say another word about it. And it was a deep thing, because I had to put it out of my mind and play. And that’s the thing about any of this. Our best moment, my best moment, is when I don’t have anything in my mind at all, I have nothing. If you had no expectations, how much better would your life be? I guess expectations must be built in to the design…

“And then I got the call, and I played on Jagger’s Primitive Cool album. Corey went with me to the audition. That was pretty wild.” He indicates the singer in his quiet reverie.

“I was working as an undercover security guard at Tower Records, and I got fired that day so I left. So we all went to see Mick,” Corey recalls with a grin. “So I was like, where you going? Fuck it, whatever. I got no job. He [Jagger] ended up producing our demo and getting in the ear of Epic [who would eventually sign the band], and then he produced Glamour Boys and Which Way To America? on the first album. He played harmonica on Broken Hearts, too.”

Living Colour went with Ed Stasium as producer on their first two albums. And even though their debut Vivid (1988) took time to impact commercially by the time the band released Cult Of Personality at the end of that year, MTV had begun to take notice of the band and placed the video on heavy rotation.

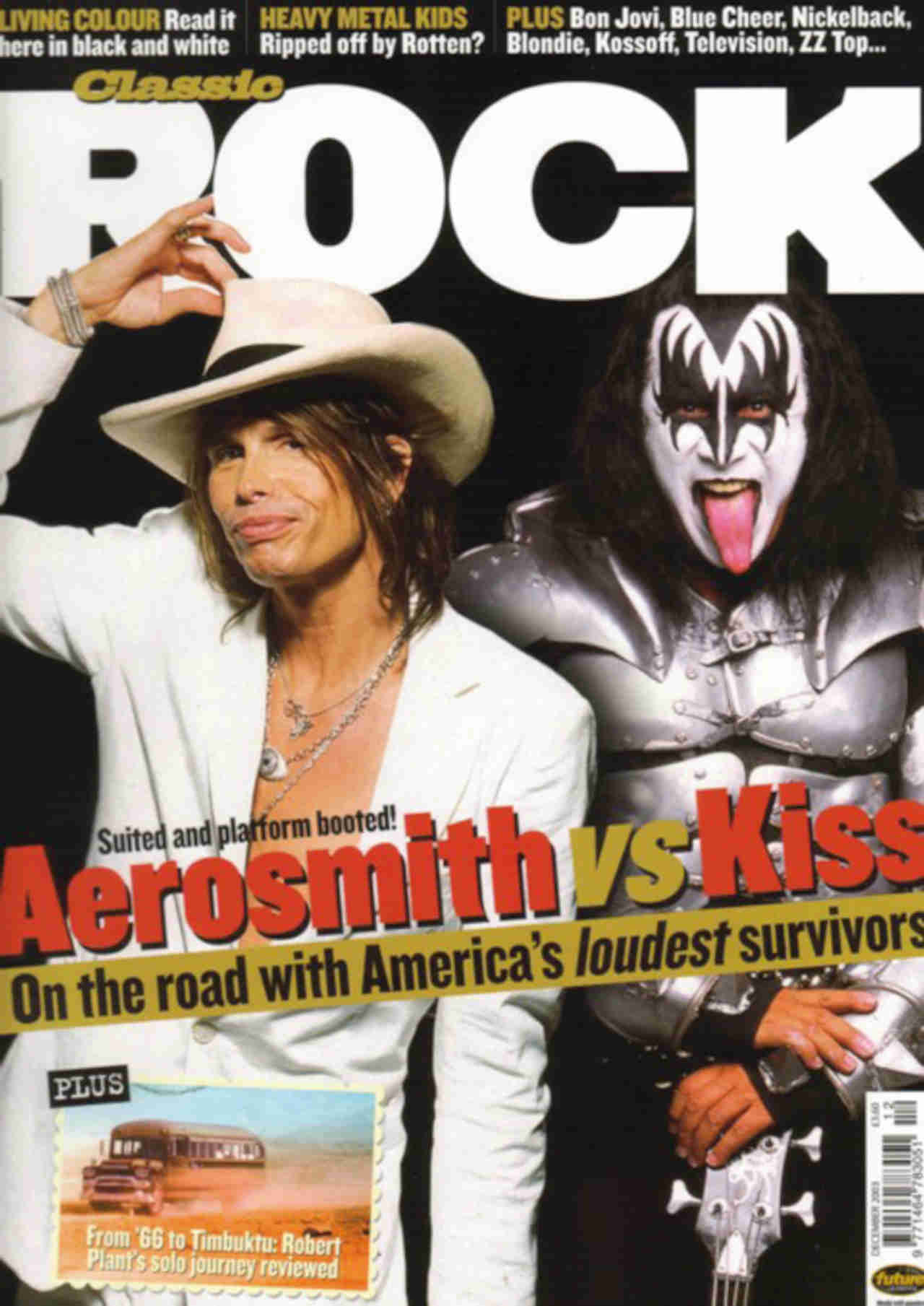

Given the musical environment at the time – best sellers that year included Aerosmith’s Angel, Def Leppard’s Love Bites and Guns N’ Roses’ Sweet Child O’ Mine – the ascendancy of Cult Of Personality is all the more surprising. Uncompromising and ragged in tone and built on Vernon’s swaggering guitar, it angrily questions authority and the figures thereof. You could safely suggest that the song lacked compromise and that its bite, both philosophically and musically, was a unique one. A year later it would win the band a Grammy award for Best Hard Rock Performance.

“If a song is creepy, if a song is rabble-rousing, as long as it gets to that unspeakable thing…” Vernon says about their first and biggest hit. “If it does that – and Cult Of Personality did that – if it manages to speak to somebody… And it did, it spoke to somebody. There was something running through culture in the background, in media at that time, and Cult Of Personality seized on something that was set back there in the collective mind, you know? It spoke to people.”

Vivid would move people too, informed by the city from which it came and eventually rose to No.6 on the American chart.

“We’re a New York band, and the New York thing has been very much a part of the Living Colour story,” Vernon says. “Vivid is really an album about New York City as much as it’s an album about anything else. You know, like Glamour Boys, Funny Vibe, Open Letter (To A Landlord), all of those things are about the city we grew up in.”

“And more about where we grew up – it was more like Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens where the three of us grew up,” says Corey, nodding in agreement.

Living Colour’s working-class ethic – Muzz Skillings had to be dissuaded from becoming a fireman to join the band full-time – saw them jump at every opportunity that came their way. They toured incessantly, Jagger upholding the original faith he had in the band by offering them the support slot on the Rolling Stones’ Steel Wheels album tour of America in 1989.

“We always worked. I think what we always felt, what we were a victim of to a degree, was our own work ethic,” Corey says. “Tastes in music are always going to change… We worked, like, almost 327 days in 1988 [laughs]. And that was to our own detriment. We thought that if we took a break they, the audience, were going to forget us. Basically, it was fear, completely. There was no letting up. We went from album to tour to album again.”

As part of the Stones’ tour, Guns N’ Roses ended up playing between the headliners and Living Colour at the Los Angeles shows. Much had been made in the press at the time about Axl Rose’s lyrics in the GN’R song One In A Million, with its contentious use of racial and homophobic insults. While being interviewed on radio, Vernon had responded to the reporter’s line of questioning by expressing concern over the lyric.

It was a brief passage in a longer conversation, but it was

pounced upon instantly by the media. Things escalated to such a point that stories abounded about an enraged Axl throwing Vernon up against a wall when both bands finally met backstage at the Stones’ shows. I mention all this to Vernon. When it comes to the so-called assault, he furrows his brow into an unusually complex shape and makes a slow shake of the head.

“That was odd; that is odd,” he says. “I would actually love to meet him. I never actually met him, because all the managers were keeping the bands apart because everybody – press, management, everyone – makes everything into a thing.” He emphasises the word with real disdain. “I’m sure he hasn’t had such a great time of it.”

Corey gives a sly grin. “He needs a hug.”

The band that Rolling Stone magazine credited for their ‘in-your-face-intelligence’ went back in to the studio to record what would become 1990’s Time’s Up. Much like its predecessor it charted respectably (No.13 on the Billboard chart), and the band won their second Grammy award. It caused a minor rumpus and a little outrage with Elvis Is Dead, but like their debut it spoke eloquently, especially in songs like the pointed Pride or the exasperated Time’s Up. The arch Love Rears Its Ugly Head (or the Soulpower remix, at least) gave them a hit in the UK.

The band toured on the inaugural Lollapalooza festival in summer 1991, and released the Biscuits EP the same year. Even their out-takes – in the form of the latter EP – bristled with invention, ideas and energy. It came as a surprise, then, to everyone not directly involved with the band when original bassist Muzz Skillings left at the tail end of the year.

Living Colour rarely skirt any question you might ask them, but bring up the subject of Muzz’s departure and, even though too polite to duck the query entirely, the band come closest to stonewalling. There’s a sense that there’s more in the unspoken than in what is being said.

“That was a painful chapter…” Vernon says. He pauses, until it’s clear that neither Corey nor I are about to break the silence.

“The thing with Muzz was really painful, and that was where we really should have just stopped to reassess things. The three of us needed to do that. You should get off sometimes. You don’t believe you can get out of that record, tour, work pattern that’s like a whip, you know?” he laughs. “It’s like, oh, you won’t be popular any more if you take a break now.”

“There were things that were happening that none of us – as Vernon has said before – had the language to deal with and to say anything about it,” Corey says. “It built to a certain point, to a fever pitch, and there was a head on it and something needed to happen.”

A number of journalists, musicians and producers had all conspired directly or otherwise to pique Mick Jagger’s early interest in Living Colour. Doug Wimbish – Tackhead bassist and extraordinary session player (he had worked with both Jagger and Jeff Beck) – had lent his voice to that emphatic chorus.

“After Muzz, Doug was the obvious and clear choice for the band because he had actually been, in a way, integral to what happened to the band in a lot of ways,” Vernon says. “There were voices in the ear of Mick Jagger, and Doug had been playing with him, and he knew that Living Colour were running around New York doing our thing, CBGB’s house band or whatever.

“And also Doug,” Vernon continues, “not to put too fine a point on it, is a motherfucker. When I first did a session with him I was blown away; I was, who is the cat playing bass? I didn’t see him, I was playing to the track. It was a Duke Bootie track for a session. I’m listening to the bass and my mind is being blown! I was like, who is this? Duke introduced me, and I was like, man, you are fucking really good.”

Wimbish joined Living Colour in time for a tour of Brazil in January 1992, and became a full-time member that summer. They decamped to upstate New York and rustic Massachusetts to work on their third album. The resulting Stain was released in spring 1993.

“The theme here is of outsiders, outcasts, of flawed characters, because a stain is a flaw,” Vernon said of the album at the time. Gone were the colourful flashes of collage and colour in the band’s artwork; instead, a stark portrait of a girl, her head caged, glared out from the cover.

On its release, the critical response was strong, while the band’s response to their surroundings seemed to suggest they were looking inward. Themes were less grand, solutions not so keenly sought. The record had a familiar beauty, but a troubled one. At the time, Corey sounded exasperated with the place in which the band found themselves, at the way that people’s perception of the band was overshadowing the band itself.

“A lot of times we got labelled good guys,” Corey says. “We were just really politically motivated, and we stood up on our soapbox and talked about the world and that’s what our gig was. We said there was a light at the end of the tunnel. Well, sometimes there ain’t. We are rounded individuals. We’re human beings; sometimes there’s good, sometimes there’s bad.

“We’re not Boy Scouts, we’re people. And as soon as people realise that we’re just people, and get off that whole thing that we’re always politically motivated, the sooner they’ll get closer to the music.”

This fractured, overwhelmed world view was reflected in Stain songs like Go Away, which cast a man weary with global problems, worn down with them; Post Man painted a picture of a disgruntled, homicidal employee. Along with Ignorance Is Bliss, the songs suggested a darkening of the group’s outlook. Stain was an occasionally trying listen (although it has held up better than parts of both Vivid and Time’s Up). And in a market where the hard rock emphasis was slowly shifting underneath them, commercially it could only ever be an album of diminishing returns. They stuck to their old work ethic and toured diligently – and sometimes brilliantly. Ultimately, though, Living Colour could only struggle to attain the former glories now so tantalisingly out of reach.

“If you have high expectations for something to happen, and that thing doesn’t happen, then…” Vernon’s voice trails off. “Like we wanted Stain to be this bigger thing, you know, and then when that didn’t happen it becomes like, who’s responsible? And in a way you can lay it at this one’s doorstep, you can lay it at that one’s doorstep. But, you know, things happen, the world changes, the context that you occurred in changes.

“It’s not to accept that someone did this or didn’t do that, and even if they did then there’s no guarantee – there are never any guarantees – but when you don’t get what you were hoping for then a lot of times in families or relationships people turn on each other. It’s, you did this and that happened!”

““We needed a really long nap,” Corey says. “Will has said since that we should have taken a pause. And you know what? We should have taken several pauses.”

Tackling the problem head on, the band relocated to London with Adrian Sherwood, determined to begin work on their fourth album. The sessions proved fruitful, with the excellent Release The Pressure, These Are Happy Times and Sacred Ground finally appearing on 1995’s Pride compilation.

“Those sessions, that was the end, that was pretty much a meltdown,” says Corey.

Vernon nods and then breaks into startling and uproarious laughter. “Pretty much… yeah!”

His laughter is a long way from the sombre and reflective statement he released in 1995 to announce his decision to quit the band. Admitting that he’d been considering leaving for over a year, in it he claimed that the band’s ‘sense of unity and purpose was growing weaker and fuzzier, I was finding more and more creative satisfaction in my solo projects.’ It continued: ‘Finally, it became obvious that I had to give up the band and move on’.

“That’s hilarious,” Corey says, giggling when I read from the original statement.

Vernon looks less sure. “I started the band and I had a real idea of what I wanted it to be. And a lot of what I wanted it to be, it exceeded anything I’d hoped for on a certain level. But there was something that I always wanted from myself and I wanted from the band, and in my mind it was clear that no one else wanted to do that. Like, it’s okay that you want to do that thing, but I’m not there. And then it became a thing of, maybe they don’t want me?”

Corey: “You know, when I first read that statement I was pissed, I was real pissed because I didn’t know where it came from and I was…” He struggles to find the words. “I didn’t know what to say, I was… At the end of the day it was, well, great, if that’s the way he feels, more power to him. I never really felt that I had to forgive him. It wasn’t something he did, he didn’t personally slag me, and he didn’t say anything that wasn’t particularly true for him, from his viewpoint, so I had to really just say, cool, what’s next?”

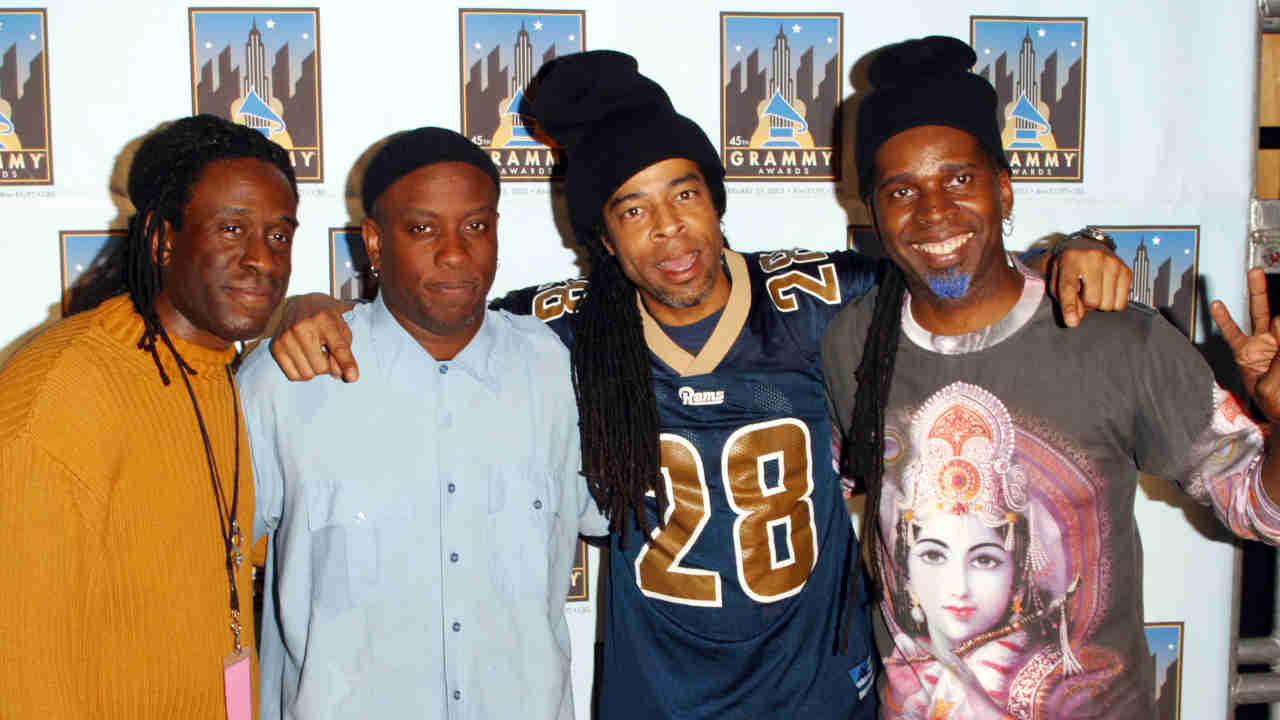

For Vernon, it was the excellent and overlooked 1996 album Mistaken Identity, followed by a new, equally overlooked band named Masque. Corey suffered a similar fate with his soulful Hymns album in 1998. Both did sessions and wrote and played music. Corey started acting again (he had won favourable reviews for his part in Oliver Stone’s 1986 Vietnam movie Platoon before the band took off). Will Calhoun and Doug Wimbish kept their rhythmic partnership more or less intact as part of rapper Mos Def’s band, Jack Johnson. Will also has his own jazz outfit, and Doug will never want for work as a session player; they also found time to form the band Headfake.

But as glittering as the four individual parts might have been, the sum of those four parts, Living Colour, was never far from people’s minds. Even Mick Jagger asked Will when the band would re-form, and Will eventually found that he was fielding the same question all around the world.

“It was the persistence of Will Calhoun that helped make this happen, actually,” Corey. “We all put out our own solo records, all four of us have done stuff, but you still get that nagging question in the back of your mind and you still get outside of your head going, that’s great; how’s Living Colour doing? What about that band? So at some point we really had to challenge that idea and challenge that notion and take it to task, and if it didn’t work then we could say, hey, see, I told you.”

Corey started to occasionally sit in with Headfake at their shows in New York. And then, as Will admits, he didn’t want to be sitting around at 60, living with regrets. So he called Vernon in December 2000 and asked him if he wanted to sit in with the band at their home from home, CBGB’s.

“That was very interesting, very interesting,” Corey says. “You’re playing in a place you’re very familiar with, and you look to your left and right and behind you and you go, what year is this?”

“On one level it felt cool and great, and on another if felt strange,” Vernon agrees. “Like, Corey was talking one time about how the passage of time was just freaky, because ten years go by and you turn around and… What happened to

everything that took place in those ten years? You’re in this moment and you’re kind of in this place again. Our first gigs had been at CBGB’s and our last gigs were too.”

They toured together to emphatic acclaim, and signed a new deal on the back of it. They then went back into the studio and, by their own admission, spent the best part of 18 months recording roughly four albums’ worth of material. Vernon puts this down to the fact that the band were still only getting to know each another again in the studio. There was, he says, a good solid chunk of time when they simply weren’t talking to each other at all.

“We had our moments, but they were early on in the process for me,” the guitarist admits. “Actually, the first set of sessions were pretty cool, and then it was that next set of sessions that we were just like, what are we doing? Things didn’t click again the way they did the first time. The first sessions, every day there was something going on. Then the next time it just bogged down in the way it does.

“You’re not always going to hit the ball out of the park. It’s part of the idea of always being productive. Sometimes you have to be with each other and maybe nothing comes up. And to be cool with that is very difficult because we all have a certain work ethic. We all came up from working-class families, shoulder to the wheel – come on, let’s go – and if it doesn’t happen that way…”

Corey nods in agreement. “Part of the reason we broke up back then was because we had that kind of ethic and our personal creative juices were running dry. It started to become very ugly, because we started to blame each other instead of looking at ourselves, and that wasn’t cool at all.”

Collideoscope addresses familiar band issues: ecology, social injustice, totalitarianism (supposed or otherwise), total power and the corruption thereof. To the greatest degree, however, the record is informed by the events of September 11, 2001. The band who grew up and continue to live in New York City admit that day’s events brought a sharp focus to their endeavours.

“That and the so-called war on terror, that kind of refocused the band on a personal level, and we really began to connect again,” Vernon says.

Corey broadens the point: “There were so many things prior to and after September 11 that should have raised someone’s ire, never got spoken about, never got dealt with. And what can you say about Bush? You have to deal with the idea that there were things going on that no one talked about, that no one dealt with and no one gave a damn about it. No one said: ‘Excuse me, that doesn’t seem right’. No one’s looking behind the curtain to see who the real wizard is.

Collideoscope makes the listener realise how much poorer we’ve been in Living Colour’s absence, without experiencing their indomitable take on things. But let’s not forget the living, breathing souls at the heart of things, the sheer will of spirit made flesh.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen next,” Vernon says. “But I’m happy with Collideoscope, because to make it and to be here has meant that we’ve all made the journey, together and apart.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 60, November 2003