It’s not easy to write about the loss of a friend. The funeral has come and gone, and yet somehow it still feels like there’s been some sort of terrible mistake and that by acknowledging it you’ll make it more real. Perhaps it’s just a coping mechanism. Other times it’s all too real. A song comes on the car radio and all of a sudden there’s this numb feeling, the rest of the journey continued in silence.

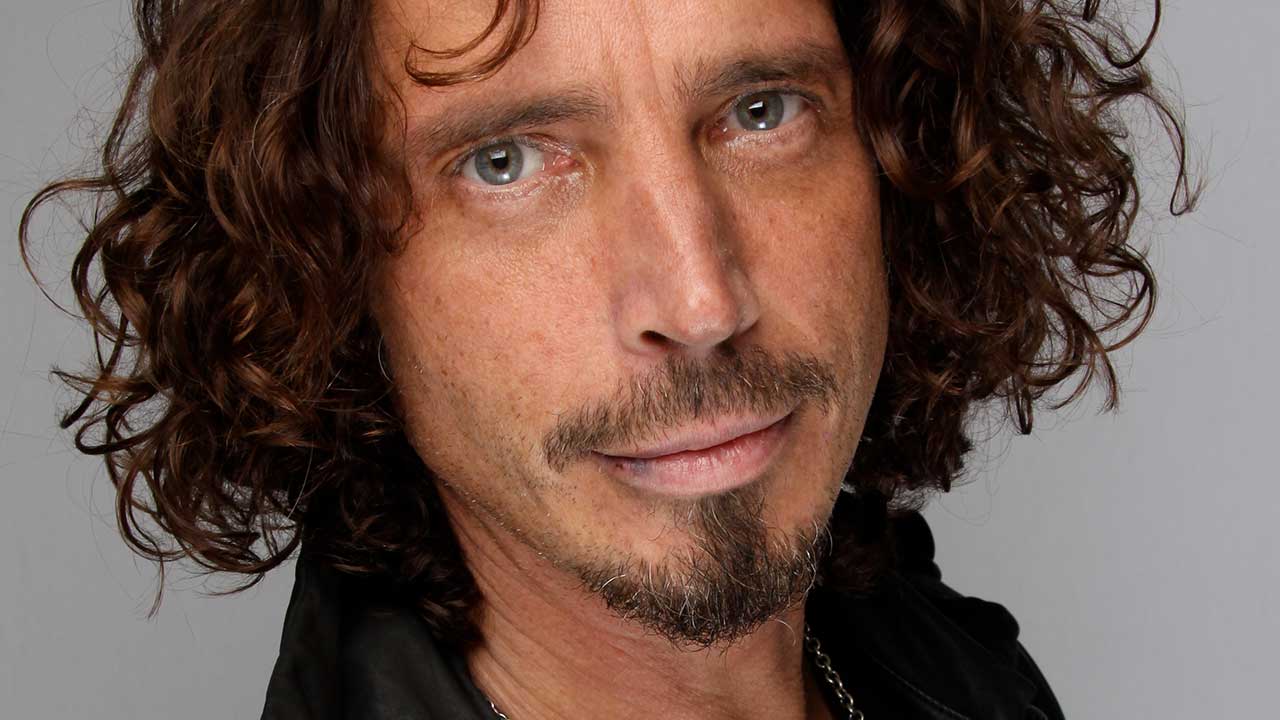

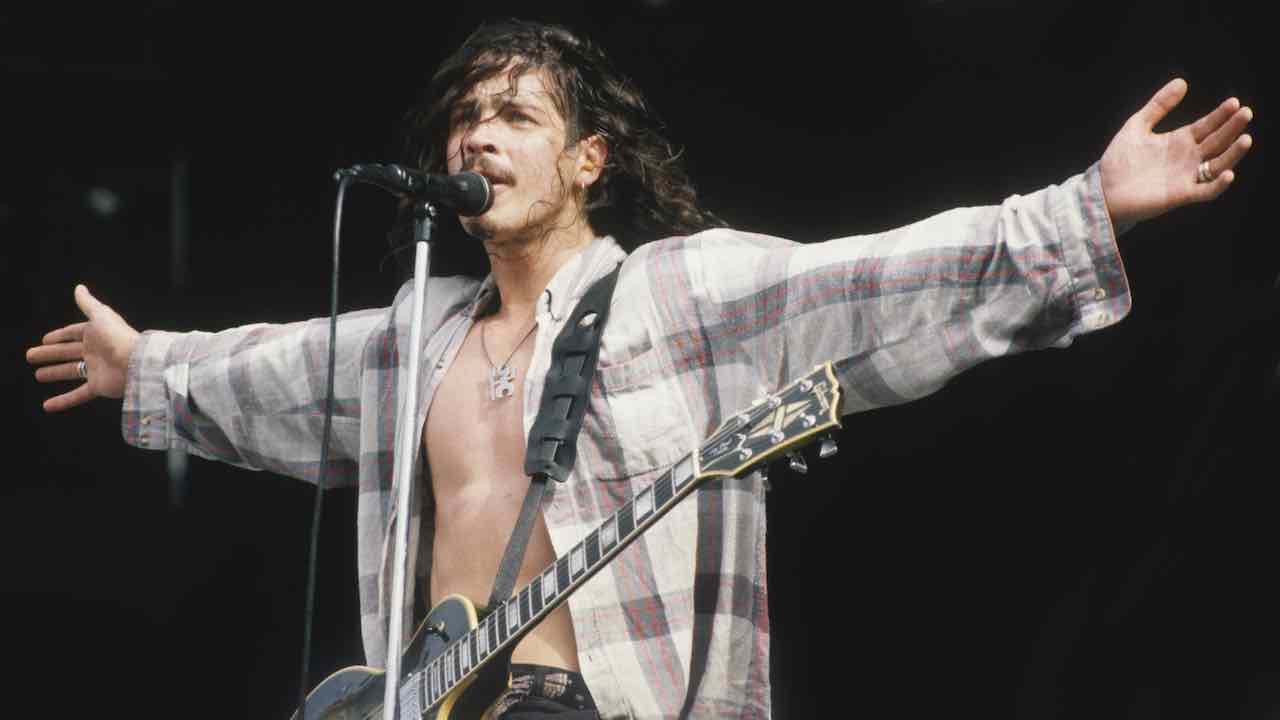

I first met Chris Cornell in 1994 when Soundgarden were headlining the Big Day Out tour in Australia. I’d heard that they could be grumpy buggers, difficult to work with, which didn’t bode well for a week spent following them around for a magazine assignment. But despite the band having acquired the nickname ‘Frowngarden’, we got along famously. The memories from that week come flooding back to me now; good times, watching from the side of the stage as Chris sang his heart out into the setting sun, sitting on Sydney’s Coogee Beach at night, sharing jokes and cigarettes as the waves broke gently against the shore, hanging out in bars shooting the shit about motorcycles, music, life in general…

You meet a lot of rock stars in this job, some great, some disappointing. You make a lot of acquaintances, you're best friends so long as you’re flattering them, but rarely do you make genuine friends who’ll be there for you when you have nothing to offer, asking nothing in return. Chris became such a friend. We’d talk for hours, long after interviews were over, sometimes inventing features just so we could hang out – a journey on Eurostar springs to mind. It wasn’t like he needed the press. Soundgarden were already huge, already among the biggest bands of ‘grunge’.

Indeed, Soundgarden were the first so-called grunge band to get signed to a major label, inking a deal with A&M in 1988, and it could easily be argued that they were the most diverse, most original band from that scene.

“They were just different,” says Terry Date, who produced their major label debut, 1989’s Louder Than Love. “It was a period of time when things were going hair metal. There was a lot of dumb, butt rock – metal without any thought. Then Soundgarden come along, and you’ve got these four incredibly brilliant people, and they’re doing heavy riffs with really smart lyrics. My goal at the time was to make music that was still going to be valid in 20 years time, and those guys completely fit the bill.”

Like I said, Chris didn’t need the press. When we met, Soundgarden had already been around for 10 years – originally with Chris on drums and vocals – and on 1991’s brilliant Badmotorfinger, three years before, they’d toured with Guns N’ Roses, been nominated for a couple of Grammys, and worked their way up from opening club shows to headlining festivals. Chris had even appeared in the 1992 movie Singles, and could certainly have done more acting if he hadn’t disliked it so much. “That’s the worst fucking thing,” he once told me. “Can you imagine having to get up at 4am and sit in a trailer while someone puts make-up on you? Then stand in front of a camera and say the same lines 60 times!”

He was already an icon, in many ways uncomfortable with the role, but at the same time aware and grateful that his music touched people on a deeply personal level. As much as Soundgarden could rock a festival audience with Rusty Cage or Jesus Christ Pose, Chris could captivate them with a solo performance of Mind Riot or the classic Fell On Black Days.

“I think that his contribution to heavy rock music was having intelligence, whilst still creating this raw, primal music,” says Alice In Chains frontman William DuVall. “He had this feral power that you associate with Led Zeppelin, that kind of swagger, but the lyrics were intelligent and introspective, and sometimes profound even when he didn’t mean them to be. He said himself that he didn’t know what Black Hole Sun was about, it was just word association, but sometimes your subconscious mind can uncover things that you, as a writer, don’t expect. I think he had a gift for that. One thing that stands out for me is he made it OK – he almost made it look easy – to imbue heavy rock music with this introspective, more singer-songwriter self-examination that one associates with Joni Mitchell or Paul Simon or Sting.”

“They weren’t doing things to make you dance and they weren’t doing things to annoy you,” agrees Terry. “They were just doing really solid, dark, brooding stuff that was really smart. Lyrics that made you think, riffs that made you want to rock really hard.”

Buzz Osborne, whose band Melvins influenced Soundgarden, describes Chris as “a little standoffish, but more to do with shyness than any kind of strange attitude”. But as his friend Chester Bennington of Linkin Park said, when you got him alone, he was really talkative: “Get him into an intimate setting and a lot of personality came out. Outside of that he was pretty quiet and reserved, really softly spoken and very gentle.” Different people see different things. William DuVall saw a man who “always exuded confidence and coolness, and looked a million bucks”. Others, perhaps understandably, saw him as introspective and moody.

I was privileged enough to work with Soundgarden many times after that Australia trip – in New Orleans, Dallas, Paris, Seattle, London and Australia again – and while Soundgarden’s so-called moodiness was occasionally apparent, it was never an issue. We even joked about it sometimes. “We’re always all dour at the same time,” Chris told me one time. “If one guy’s happy, we make him leave the room until he comes back in a bad mood, like he should be.” Over the years, however, we had more serious conversations, both on and off the record.

It was no secret that Chris had a dark side, a cloud on the horizon that never really seemed to go away, and in many ways it’s what made his music so precious, the knowledge that while we may go through depression alone, we’re not alone in walking that path. It was there in so many of his songs, and now I can’t bring myself to listen to them. Even the songtitles are too much: The Day I Tried To Live, Like Suicide, Fell On Black Days…

The most difficult, personally, is Blow Up The Outside World. ‘Nothing seems to kill me, no matter how hard I try…’ He dedicated that song to me when Soundgarden played the Forum in Los Angeles a few years back, knowing how much I loved it, and what it meant to me: ‘Nothing seems to break me, no matter how hard I fall. Nothing can break me at all…’ Sometimes you have to kick the black dog in the teeth and tell it to fuck off, and that’s what Blow Up The Outside World was doing, why it was so very special. Now it would just make me cry, not least because he seemed to have finally beaten his demons.

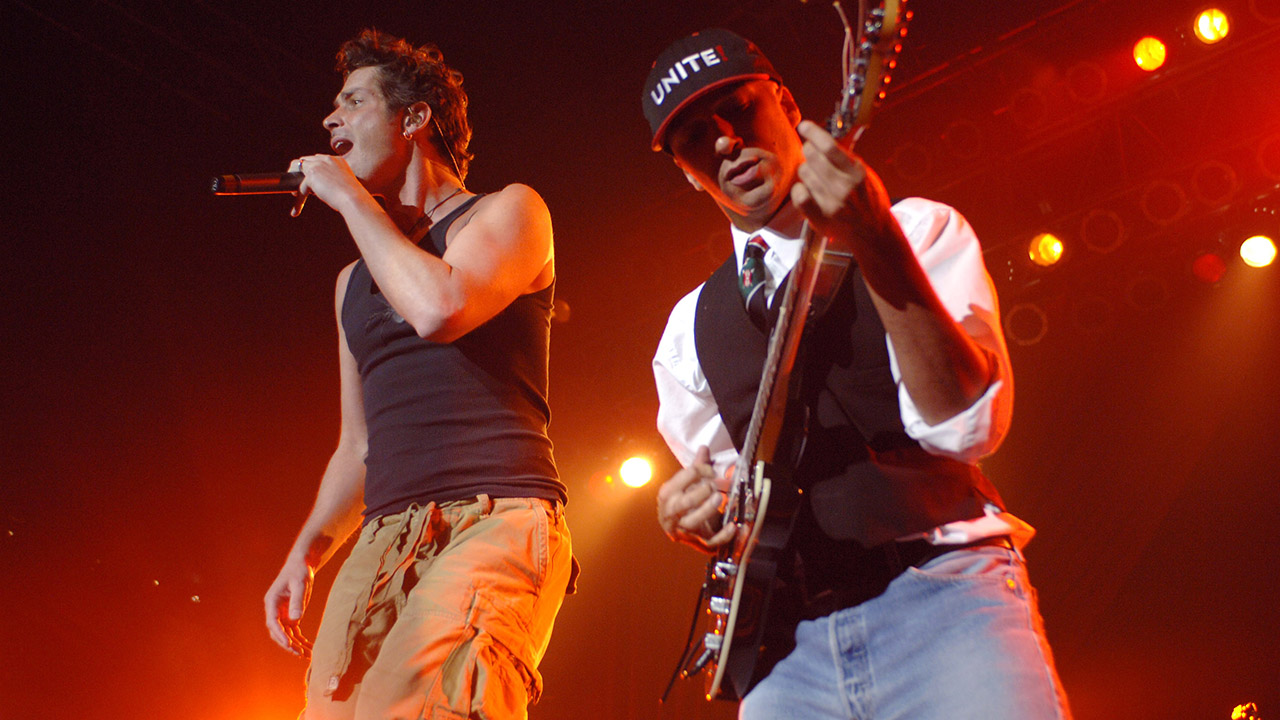

When Soundgarden split up in 1997, it seemed right somehow. They had achieved more than any band could possibly hope for – 1994’s Superunknown and 1996’s Down On The Upside were both massively successful albums – and they were leaving on a high note, musically if not perhaps personally. Despite the sombre tones of Chris’s debut solo album, 1999’s Euphoria Morning, he seemed to be in a good place, and likewise seemed in good spirits when the new band Audioslave – born from the ashes of Rage Against The Machine – got together in 2001. Unfortunately, this was not the case, and a year later the release of their self-titled debut was almost derailed when Chris checked himself into rehab, even conducting an interview with Metal Hammer from the clinic payphone.

“I didn’t come here because of a court order or anything like that,” he said at the time. “I’ve been on and off drinking and other drugs for years and years, maybe 12 years or so. But I’m a new father and I’ve got a new band and so much to be excited about. I really wanted to get that aspect of my life in check.”

Behind the scenes, Chris was going through a messy separation with his first wife, ultimately leading to divorce. But he remarried in 2004, fathering two children with his new wife Vicky, and, again, he seemed to be on the upside. Audioslave may have been relatively short-lived, releasing just two more albums – Out Of Exile in 2005 and Revelations in 2006 – before splitting up in 2007, but the solo work continued, and Chris even co-wrote and performed You Know My Name, the theme tune for the Bond movie Casino Royale.

When Soundgarden reformed and released their well-received King Animal album in 2012, I asked Chris if his newfound happiness had affected the writing process, perhaps making it difficult to relate those darker emotions that made the band so universal.

“It’s made the process more fun being in a better place mentally, and not having the emotional ups and downs that I may have had before making Soundgarden records,” he said. “But there’s definitely moody stuff that I didn’t have to invent. I didn’t have to pretend to be a dour, sad person… Going from moment to moment feeling like I’m in a somewhat better mood doesn’t mean that I’m not having lots of moments of inner panic and freaking out.”

Understandably, there’s been a great deal of speculation about what happened to Chris in his final hours, his every word and action analysed, particularly the last song which included a section from Led Zeppelin’s version of In My Time Of Dying. There was also the fact that he had apparently over-medicated with anti- depressants – you know the ones: ‘may cause suicidal thoughts’. If nothing else, the fact that he was taking medication showed that he was trying not to succumb to the darkness, the black dog that finally bit him in the early hours of May 18 in a Detroit hotel bathroom.

Honestly, I’d rather not think about it, and many musicians and friends we approached felt unable to talk about Chris so soon after his passing. What I can say, as his wife Vicky said, is that Chris would never have intentionally hurt those he loved and who loved him. Ironically, he told me as much in 1994 when we talked about the death of Kurt Cobain: “You don’t know what drives somebody to do that, but if I ever committed suicide, I would do it in a way that meant no one ever knew that it was suicide – because to me, the biggest fear of killing myself would be what it would do to my friends and family. If things are fucked enough that I want to kill myself, the last thing I want to do is go out and really fucking hurt a bunch of other people.”

Moreover, Chris and Vicky were heavily involved in charity work, setting up the Chris & Vicky Cornell Foundation in 2012, to benefit homeless or neglected children, and making what is described as “a huge donation” to the Childhaven music therapy programme, which helps children who have been affected by abuse or trauma. The foundation also donated “a significant amount of money” to Seattle nonprofit organisation YouthCare, and employee Brittny Neilsen fondly recalls Chris visiting the place.

“He didn’t come in with a huge entourage,” she says. “He came in just as a normal person, and he was never talking about how much money he was going to splash on this programme, he was only interested in what we were doing. I think that attitude, that leaning in and engaging those people and taking a genuine interest in them, letting them know that their dreams and aspirations are important, meant so much. It showed them that they were much more alike than they were different. Taking the time to let them know they are of worth meant more than anything.”

The funeral, held on May 26 at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles, went some way to showing how much Chris Cornell meant to the world. Among those paying their respects were friends and family, movie stars and musicians.

“It was beautiful and heartbreaking in equal measure,” says William DuVall. “Sitting there and listening to his music being played over the room at his funeral, it was astounding, and obviously really sad. It doesn’t matter who you are or what you do; as a person we have people that we look up to, and Chris Cornell was one of those people that we all looked up to. And everyone at that gathering felt that we’d lost someone that documented our lives and we held in the highest esteem.”

We talked, one time, Chris and I, about how maybe people who never suffered from depression, never knew the lowest of lows, also never knew the highest of highs. In which case, Chris soared with the eagles. Rest in peace, friend. No one sings like you anymore.

To find out more about Childhaven, visit https://childhaven.org. For YouthCare, visit www.youthcare.org.

There are many organisations who can help those struggling with their mental health

Mind

Mind provides advice to anyone experiencing mental health problems.

www.mind.org.uk / info@mind.org.uk / Tel: 0300 123 3393 / Text: 86463

Samaritans

Samaritans offer a free, confidential, non-judgmental service for people to talk through their worries.

www.samaritans.org / jo@samaritans.org / Tel: 116 123

Help Musicians UK

The charity is leading a campaign to find solutions to mental health issues in the music industry. It offers advice and support to musicians of all genres and stature.

www.helpmusicians.org.uk / Tel: 020 7239 9103