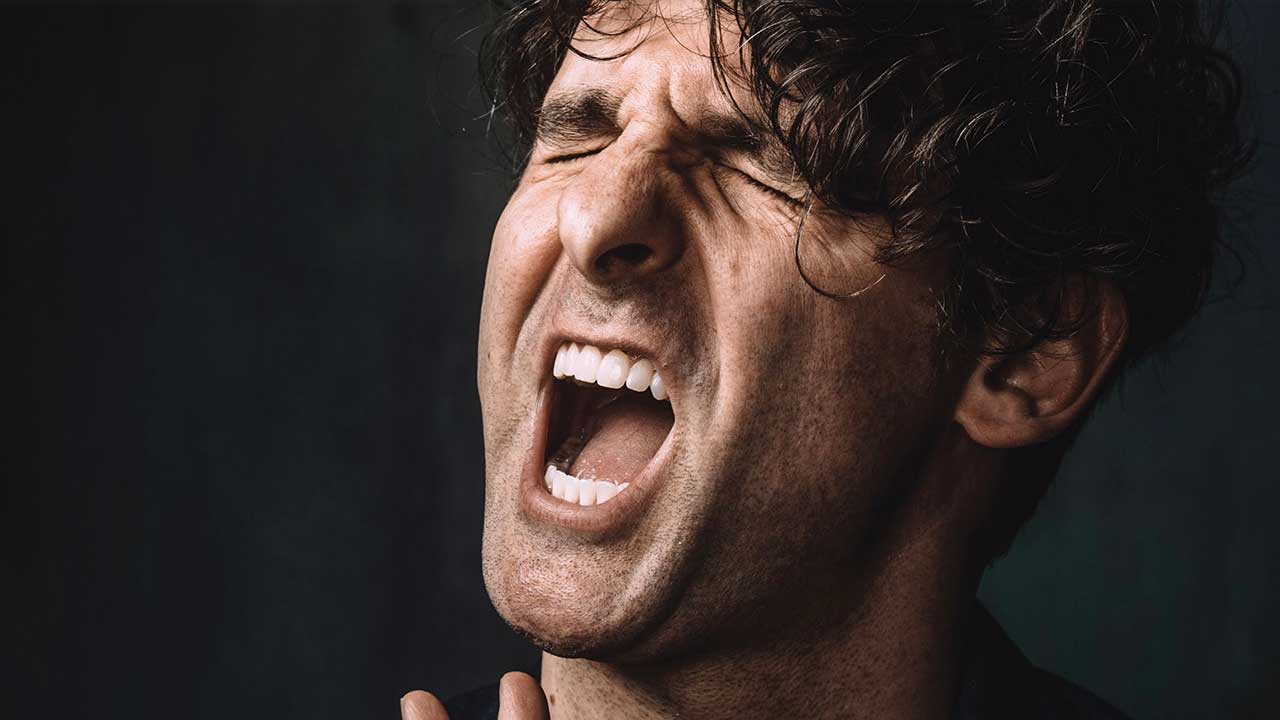

As it is with so many fireballs of rock’n’roll (Prince, Little Richard, Jimi Hendrix, Alice Cooper, Kurt Cobain, Angus Young…), to meet Adam Weiner off stage is to meet a different person from the Adam Weiner on stage.

He’s polite and earnest. He’s approachable but keeps largely to himself. He doesn’t drink. He doesn’t shout or make a scene. But put him on stage, or in front of a camera, and it’s a different story.

Every week since March this year, Low Cut Connie’s piano-thumping mastermind has been singing, playing, gesticulating, sermonising and sweating profusely for an audience he can’t see. Often he’s stripped to his underwear by the end, writhing on the floor of his Philadelphia apartment like a man possessed. It’s like watching an evangelical church service led by the pale Jewish love child of Little Richard and Tina Turner.

Welcome to Tough Cookies, Low Cut Connie’s lockdown live-stream operation. A warm, noisy cabaret of glitz, grit and good times, it’s an exaggerated montage of all that Weiner and his band, an ever-changing cast, have cultivated since 2010. It’s raucous rock’n’roll that begs to be danced to; Jerry Lee Lewis-rivalling piano boogies; affectionate tales of underdogs and misfits (peaking on their previous two albums Dirty Pictures Part 1 and Part 2)… all of which entered the global spotlight in 2015, when then-US president Barack Obama included their song Boozophilia on his summer Spotify playlist.

Over the past six months, with the band’s usual touring on ice due to COVID, Tough Cookies has grown substantially. As Weiner tells us, it’s become more than just a stopgap.

“It’s very quaint to think that everybody was thinking: ‘I can’t take this shit no more, ten days!’” he says with a grin. “Now it’s five and a half months. But at that point [when they did the first live stream] people were saying: ‘Can you please do something online? Just something?’ So we announced that we would do three performances. We had no plan whatsoever; me and Will [Donnelly, Low Cut Connie guitarist and the only other constant band member besides Weiner] would just do whatever we felt."

For the second Tough Cookies show the Washington Post sent a photographer over to the flat, where Weiner and Donnelly have carried out all their streamed shows, which have included Zoom interviews with guests such as Chuck Prophet and Dion.

“It’s over forty hours of this shit,” Weiner says, laughing, “And I’ve realised that I can do anything I want on these shows. I can do comedy, I can strip, I can sing, I can dance, I can talk politics, I can grieve with people. We laugh, we cry, I can give them inspirational messages, I can lead them in aerobics. Two weeks ago I did horoscopes. The other night we did an after-party broadcast and I sat there eating chicken tacos while people asked me questions. People are so hungry for live entertainment, making them feel in the moment.”

The best thing about the format, he suggests, is how democratic it is. Nurses have streamed Tough Cookies in intensive-care units. OAPs, young adults and children are among their viewers. People have tuned in from more than 40 countries. It’s an optimistic outlook, even if he does miss the face-to-face physicality of touring.

“I’ve got messages from people in Japan and Australia who get up at six a.m. to watch live,” he enthuses. “We have a lot of viewers in South America, we have a fair number across Eastern Europe, I’ve got messages from people in the Middle East… I mean, when’s the next time I’m gonna get to tour Lebanon or Ecuador?”

In the midst of all this, Weiner has been doing promo for the new Low Cut Connie album, Private Lives, a sprawling collection of soul, sleaze and rock’n’roll spanning 17 tracks. Sometimes joyful, often heartbreaking, laced with acerbic wit, it took more than two years to record. Sessions were packed into pockets of breathing space in an intense touring schedule, in multiple studios across America, involving more than 30 guest musicians. And it almost killed its creator.

Having already wrestled with depression for a number of years, Weiner found himself at an ominous low point after a new course of medication went badly wrong. He was diagnosed with serotonin syndrome, and plunged into a long, tortuous episode that would stretch from 2018 until the autumn of 2019.

“I became… fairly catatonic,” he explains. “I had a lot of difficulty getting dressed and taking a shower and making the gig. But actually the performance itself would bring me clarity again. I think the adrenaline would sort of bring me back to my normal brain.

"I was doing a festival in England, and afterwards I got lost, cos I went through the crowd and I was hugging people, and the next thing I knew I was in the woods and I was completely lost and disorientated. I jumped over a fence and I landed funky and destroyed my left ankle. It’s well over a year later and I’m still rehabbing my ankle.”

He was also dealing with a torn rotator cuff (muscles and tendons around the shoulder) from earlier, plus a back injury from all the years of heaving pianos around. It’s left him with a joint disorder which he still does yoga for every day. In the end, curiously it was touring with a hiphop artist, New Orleans ‘bounce’/twerking pioneer Big Freedia, that brought him back from the brink.

“It was pure live entertainment,” he recalls of the tour. “We had dancers, we had twerking, we brought the audience on stage, it was sexy, it was very soulful, we did some gospel. And all over the United States we had black, we had white, we had gay, we had straight, old, young, we had such a diverse group of people in the same room.”

It was just the life-affirming boost Weiner needed in order to feel like himself again, and to complete the album.

“After the tour was over we got Private Lives finished,” he says. “It wasn’t until then – two years plus into making it – that I said: ‘This is a powerful album.’ It’s a mess, but it’s a beautiful mess."

The real roots of Private Lives – and of Low Cut Connie – go back much further. Born in 1980, Weiner grew up in a strict conservative Jewish household in New Jersey. Ideology and practises were “old-school”, with women separated from men for various elements. Synagogue services were very formal and almost entirely in Hebrew.

The religion itself hasn’t stuck with Weiner, but the heady, old-world voices of cantorial singers laid foundations for his whole vocal delivery style. Not that he realised it at the time.

“Some of these cantors were Holocaust survivors,” he recalls. “Some of them were from Lithuania or Poland and they had this amazing, old-world way of singing – I call it ‘Jew soul’. That was very influential on me. When I came of age I realised that I was fairly atheistic in terms of religious faith, but [later] I reconnected with my Jewish upbringing in my adulthood and through my performances… I have seen spiritual resonance and spiritual uplift through live performance and music that is certainly what I would call religious.”

He took piano lessons because the family had a piano at home and “that’s what you did”. Early years involved doggedly learning Broadway tunes and Barry Manilow hits. But it was the sight of Buddy Holly and The Big Bopper, alongside 1950s rock’n’roll stars such as Little Richard, in the 1987 rock’n’roll biopic La Bamba that captured Weiner’s imagination at a young age.

I was in some shitty band, but I remember in the middle of the performance I said: ‘If you scream loud enough I’ll take my shirt off.’ And everybody screamed, and I took my shirt off.

Adam Weiner

In school he was a shy boy who was “terribly bullied” (“having the last name Weiner – A. Weiner – was not a help to the situation,” he says with a wry smile) and struggled to talk to people. On stage, however, he found that something clicked.

“Being on stage was completely carefree for me,” he says. “I remember being in eleventh or twelfth grade, and they did a Battle Of The Bands. I was in some shitty band, but I remember in the middle of the performance I said: ‘If you scream loud enough I’ll take my shirt off.’ And everybody screamed, and I took my shirt off. And everybody was like, where the hell did this guy come from?!’”

All the while, a fearsome work ethic was being instilled in him. His father worked long hours in the fabric trade in New York City, and by the time Adam had his license he was driving him to the bus station at 4.30am.

“Then he would get home at, like, nine o’clock at night,” he says. “And he did that for twenty-seven years. I always had it instilled in me that you get up and you put in a shift, and whatever you’re working towards you give it a hundred and twenty-five per cent."

At 18 he moved to the city to study at NYU, and began years of dues-paying as a pianist in restaurants, gay bars, jazz clubs, cabarets, wherever he could get a gig. He spent one year of his studies in Memphis, working at a local radio station and immersing himself in the music of the south.

“I would travel into Mississippi and go to the grave sites of blues artists that I loved,” he says. “I would visit different juke joints and honky-tonks to see blues, soul music, country music. I went to Louisiana on many trips and would perform and meet people in rural Louisiana, New Orleans…”

During this time he went to Reverend Al Green’s church in Memphis, where Green (the soul singer best known for Tired of Being Alone) was still a pastor. Weiner was the only white person present, and the experience would resonate throughout his subsequent years of performing.

“I cried my eyes out, we had our arms around each other,” he remembers. “Holding hands with everybody around me was very powerful. I would go to churches and listen to gospel music, which I still listen to. Even though it’s not a theology for me, the spirituality of music moves me greatly.”

After graduating he was based in New York for 13 years, and also spent two years in Montreal, one in Austin, and had a spell where he was touring so much that he “didn’t really live anywhere”. In 2005 he met his wife, Adriana, at which point he was playing piano at a Connecticut ballet studio by day and a gay bar by night.

Asked what other jobs he’s had besides playing piano, he lets out a laugh and says: “Are you ready?! Oh shit, okay…” He then spends the next few minutes outlining an enormous, oddball cv that includes jobs in vintage clothing stores and a doctor’s office, as a ‘fragrance model’ (“the person who stands in the shopping mall and tries to spritz you with Chanel”), a children’s theatre director, an English and French tutor, a telemarketer, a hospital file clerk and a cabaret director. After 9/11 he worked for a foundation running stress workshops for pre-school children in The Bronx.

“I met all of these families in very, very poor areas of The Bronx and Washington Heights and NYC, mostly black and Puerto Rican families, Dominican families. I got to know the teachers, the parents and the kids, and I would spend my days talking about stress with them. I was not qualified for the job, but I certainly loved the opportunity to do it.”

But it’s his first regular piano job, at a New York drag karaoke joint called Pegasus, that has really stayed with him. “I worked there in 2001, 2002. I was twenty-one, I was just finally allowed to work in a bar like that. I played there a couple of nights a week. The people I met there were outrageous. They were soulful. They were hysterical.”

It was here, in an underground world of drag stars and colourful characters, that Weiner began to hear stories. Bizarre stories, amazing stories, sad stories, joyful stories. Myriad windows into a plethora of private lives. All of it alongside valuable lessons in how to entertain people – and how not to.

“I would bomb on some nights and kill on other nights,” he says with a grin. “I learned that you have to look good, you have to not be boring, you have to sound good and you have to remember that you’re not giving a concert, you’re there to entertain people. There’s a difference. It’s not a piano recital, you’re there to make people dance, make people laugh, cry, smile…”

He has many more stories like that. Such as the Italian restaurant in Queens frequented by the Mob (“they were really good tippers!”). The pot-luck dinner at a college in Norman, Oklahoma that turned out to be an anarchist squat. Countless “fascinating” people met in diners, motels and petrol stations across America. The nine-week shoestring solo tour of the UK and Europe (at the time Weiner was performing as ‘Ladyfingers’), armed with a backpack, a guitar and a wooden box that he’d stand and stomp his foot on. Jet-lagged shows at “the shittiest places” in Northampton, Berlin and beyond – usually without a bed for the night and generally operating at a very “punky” level – toughened him up ruthlessly.

“I have a lot of friends here in Philly who are boxers,” he says, by way of an analogy. “The real training to be a professional boxer, besides the fact that you have to do dozens and dozens of fights, is you have to get your ass kicked. You have to get beaten up over and over until you learn not to get beaten up. I’ve bombed. I’ve bombed more times than I’ve killed. I had to go through that to become the performer I wanted to be.”

Come the summer of 2015, Low Cut Connie had been going for five years, released three albums and made minimal headway, and Weiner is debating whether or not they should continue.

Then Barack Obama, the US president, publishes his summer Spotify playlist. It includes tracks by Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, the Isley Brothers… and Low Cut Connie.

It was a turning point. While presidential approval didn’t generate the fame and fortune it might have done in bygone decades, it did put Weiner in a position, finally, to make the band his full-time job.

“You have to remember,” he says, “I did this in a completely unsuccessful way for ten to fifteen years before I saw any success. And because I saw it as a higher calling, I continued to do it.”

It’s precisely because of those years that he relishes all aspects of band life, even in today’s odd times. The Tough Cookies live streams, the promo schedule, the shows, the social media, the fan interaction, the work…

“It’s a privilege,” he says, with the sort of unfussy sincerity that prevents you from rolling your eyes. “I’m not in it for money, I’m not in it for sex, I’m not in it for drugs, I’m not in it for glory. I see this as a higher calling. It’s something that chose me, and I really can’t do anything else.

"I don’t take it lightly. I want to go further. I feel very lucky.”