“I tend to plough my own furrow. I’m focused on what I’m doing and not comparing it with what other people are doing,” says Maddy Prior as Prog rounds up an afternoon’s talk about her early life and Steeleye Span reaching 50-plus years. And maybe because of that outlook, Prior is probably one of the most recognisable voices in folk, and folk rock music – and her face is pretty recognisable too, after a string of hits in the early 70s with Steeleye Span led them to be staples of shows such as Top Of The Pops.

From an early age Prior loved to sing, and was encouraged to do so and take part in competitions. In the late 50s the family relocated from Blackpool due to her father’s job – drama writer and novelist Allan Prior co-created hit TV show Z-Cars and later Howard’s Way – and Prior found herself in the Roman town of St Albans, which had a thriving music scene and was a folk epicentre.

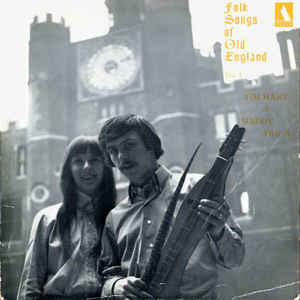

Meeting like-minds such as Donovan and Mac MacLeod in the local folk clubs, in 1965 she teamed up with guitarist/vocalist Tim Hart both professionally and romantically and formed a duo that went on to release two albums on TeePee Records, Folk Songs Of Old England, volumes 1 and 2. By 1969 Prior and Hart wanted a change, and it came in the form of former Fairport Convention founder and bassist Ashley Hutchings. Together they created an electric folk band, Steeleye Span, whose popularity remains today, largely because of their enormous, resonant 1975 hit All Around My Hat. While in Steeleye Span, Prior would meet her future husband, bassist Rick Kemp, who replaced the departing Hutchings in 1972 (he was off to form The Albion Band).

Prior has released solo albums, joined June Tabor as the duo Silly Sisters, played with The Carnival Band and guested with Jethro Tull, Mike Oldfield and Status Quo. In 2001, she was awarded an MBE for services to folk music. And passing on the torch, Prior runs Stones Barn arts centre in Cumbria, where she holds weekend singing classes and residential workshops in folk music, often with her daughter, singer-songwriter Rose Kemp.

Today, in Ye Old Fighting Cocks pub in St Albans, Prior has been filming a feature about Steeleye Span, and pondering their 50-plus years. A May tour is planned

for 2022, but in the meantime, a document to the band’s life to date exists in the release Est’d 1969, featuring the current line-up of Prior, Liam Genockey (drums), Julian Littman (guitar, mandolin, keyboards, vocals), Jessica May Smart (violin, vocals), Andrew ‘Spud’ Sinclair (guitar, vocals), Benji Kirkpatrick (bouzouki, guitar, mandolin, banjo, vocals) and Roger Carey (bass, vocals). “I’ve been very grateful to have been a working musician for years,” Prior reflects, now aged 74. “I had a week working in a Wimpy Bar while on holiday at the end of school for which I earned £10, and at the same time I’d done one gig with a band for £8. I thought, ‘I’ll do this for a living.’”

You were born in Blackpool, but found yourself being uprooted to Hertfordshire at a young age. What was that like?

I was 11 when we moved from Blackpool to St Albans, which has just got to be one of the biggest culture shocks you can come across. The Harpenden grammar school girls couldn’t understand me, nor I them [laughs], but I caught on quick and soon talked ‘like that’ [adopts over-the-top posh accent].

How did music enter your life?

Back in Blackpool, my father had realised that I could sing so he took me to someone on his paper, the Blackpool Gazette – he was a reporter before he became a drama writer – who did music reviews. They said, “Oh, we’ve got a little songbird here”: so they sent me off to join the Co-op choir, which was run by Miss Whiteside, where I learned a lot of songs. You didn’t learn technique at that age, just a bit of repertoire, and you’d enter these competitions, at which I was absolutely useless [laughs].

So you could sing, but what about instrumentation?

I wanted to play the violin and when we came down south we got one – we took it or hired it from the school. But my father said, at the end of a year of me scraping away, “Do we want to play the violin? We’re not getting anywhere.” It must have been great for him as a writer having that going on. So that got shelved and I started to play the banjo, then guitar. But that’s six strings and I never got on with six strings. I was passionate about the banjo but then Tim [Hart] picked it up and played for two months. He was so much better than me so I put it down again – and so did he, which was really annoying! [Laughs.]

What were you listening to when you started singing folk songs?

I started with American material, people like Woody Guthrie, and Joan Baez. There was a very good record shop in St Albans, Mark Greene’s Record Room, and he’d been around for a long time [the shop opened in 1957]. He was good with young people, there were booths to sit in and listen to music and he knew quite a bit about music. It made a huge difference to the St Albans scene. [The Zombies and Donovan shopped there too – Record Shops Ed.]

Folk music was in the pop charts then, wasn’t it?

Yes, with Joan Baez you have Bob Dylan and others crossing over into the mainstream, it was cool at the time to be interested in folk music – but not particularly English folk music. My friends would come with me to folk clubs. They didn’t always like it but it did depend on who was on, and there was a lot of humour in the folk clubs, a lot of comedians because it was like stand-up with music.

From there you get Mike Harding, Jasper Carrott…

And Billy Connolly!

So these clubs were your social hubs and where musicians met, then?

Yes, we knew Donovan that way, and Mac MacLeod who played with Donovan, then was in the band Hurdy Gurdy – he was Donovan’s Hurdy Gurdy Man! Donovan lived in Welwyn Garden City but came over here a lot because there was a lot of music. There was The Cock, The Peahen, The Red Lion and The Goat. They were all very old, dark Victorian places, very dusty.

With the Roman ruins, the Abbey, the beautiful city and gardens, St Albans must have been quite inspiring?

It was – Blackpool was quite flat and the bright lights were for tourists. We came here and these old, old buildings and trees that were upright, not blown at an angle by north-west winds! It was another world. I loved it. You’d wander around with your friends and sit in the nearby park [Verulamium, a former Roman city and the site of the ruins] and sit and play music. We had a great time, very casual… and a few drugs, but nothing untoward. But I wasn’t into that, I’ve always been a drinker! [Laughs loudly.]

The folk scene was, and still is, quite political.

The folk scene has a left-wing bias. Guthrie was a big voice, and spoke of the issues of the time in my world. If there was an issue I would find a song that was old that reflected it, like Hard Times Of Old England – which we’re looking at again, unfortunately, it never goes away. We’d look at old songs about new issues such as Blackleg Miner, which we sang all the way through the Miners’ Strike [in 1984], and when I first sang it was an interesting historical document from about 1844. Now it’s an interesting historical document again.

How did you meet Tim Hart and start gathering songs?

He was part of the gang and so we got to know each other. I was in a duo with Mac MacLeod [Mac & Maddy] but also working as a roadie, driving American musicians around. A duo, Sandy and Jeanie Darlington said to me, “You should stop singing with an American accent, you’re shit at it.” So they gave me loads of folk tapes to listen to, and initially it was like, “Oh God, all these boring old guys”, then eventually I got my ear in, which you do with music. I listened and listened, and eventually you hear the song and get past the presentation.

What were the first songs in your repertoire?

The first song we got out of [Thomas D’Urfey’s 18th century song book] Pills To Purge Melancholy, Long George, which was rude, of course! Our tunes often had nothing to do with what is written on the page, we sort of made a stab at it and put in words that we liked. We also went to Cecil Sharp House and listened to more or less the whole library. It took us about four weeks. I heard a lot of material and a lot of singers and styles.

The material was working and you were getting popular when you played live. So what happened next?

Tim and I made two albums – and it was really unusual for folk artists here to have an album. Tony Pike came along and picked us up for Teepee Records. We made the records in his kitchen, on a Revox, in his house in Putney. That was the first album, Folk Songs Of Old England, and for Volume 2 the budget went up and we had two Revoxes [laughs], so we could overdub. It took us as long to make it as it took to play it. The albums gave us a lot of kudos and exposure.

And Ye Old Fighting Cocks’ exterior was used on the front cover. Do you remember that day?

I do – it was a very cold day and we had hot buttered rum by the fire. We picked this place because it’s ‘Old English’. It’s supposedly the oldest licensed public house in England.

You got to know the influential folklorist and singer Bert Lloyd, didn’t you?

We did. He was an inspiration to the whole of the folk revival, along with Ewan [MacColl]. He was the founder and artistic director of [influential folk label] Topic Records for a long time, and the releases have the most amazing covers and names, he was really good with words. He brought an elegance to the revival and a light touch. Although he was a communist he wasn’t banging a loud drum. He brought Tim and I songs like The Gardener, which Steeleye recorded on Est’d 1969.

Tim had said there was a glass ceiling for the progress of folk musicians. Were you ambitious?

You don’t go into British folk music with ambition, really, but we were. We’d been playing the clubs as a duo for three or four years. We were limited by the amount of people in the venues, the amount of people in the band – and we wanted to play louder. Everyone had been talking about going electric as Dylan had. There was this conversation about who was gonna do it. None of us had the budget for it. But Ashley [Hutchings] had a record company behind him…

When did you encounter Ashley?

We’d played on festival stages with Fairport Convention, and Tim and I were around north London when they were getting Liege & Leif together. One night, when we were living in Whitehall Park, Archway, he came to dinner with [Irish folk duo] Terry & Gay Woods. We were sat around a table and they said, “Do you want to join a band?” We said, “We’ll have a try-out tomorrow,’” and that went quite well.

When did you actually become a group?

Autumn 1969. We rehearsed in a friend’s house in Wiltshire and were “getting it together in the country”, which was a terrible idea. We spent three months doing it, it was quite strange. Ashley had been in an accident [Fairport’s tour van had crashed that May] and wasn’t on an even keel. Two couples – Terry and Gay and me and Tim – as referees was not the way to run a band.

How did you arrive at Steeleye Span’s name?

During the three months in autumn 1969. We came home a lot and we were in St Albans, at Tim’s house, which was the vicarage. [Folk artist and Dave Swarbrick collaborator] Martin Carthy was staying there and looking through some books, late at night with Tim – as usual. Looking at a book of Norfolk songs [and one called Horkstow Grange from 1760], Martin says, “Look at this: ‘Pity them that suffer, pity poor old Steeleye Span.’ Isn’t that a great name?” Tim said, “That’s the name of our band.”

Martin went on to join Steeleye, didn’t he?

Yes, we made the first album [Hark! The Village Wait] in March 1970 and then Terry and Gay left and they assumed it would all collapse. That didn’t happen. We re-formed with Martin on guitar and keys and Peter Knight on strings and keys. Then we did some gigs – that first line-up never gigged.

Was there any resistance from the folk purists to you plugging in and rocking out?

We were all about being electric, right from the start. Martin Carthy was one of the loudest electric players I know. Some people didn’t like it, we might not have been very good at it right at the beginning. We were loud and toppy with our twin reverbs, speakers to tear your head off. Mix my voice with a fiddle… People said they couldn’t hear us, the noise was unbelievable.

You got so popular that you attracted some celebrities. How did you get Peter Sellers on Commoners Crown?

We’re sitting around and someone said, “What this needs is a ukulele.” I have no idea why; at the time the ukulele was completely unknown instrument. We said, “Does anyone know anyone who has a ukulele?” Then Bob [Johnson, guitar] said, “Peter Sellers does.” So we got in touch and he said yes. He was so delighted to be asked but also terrified. We sat in with him, at Morgan Studios, and he was brilliant – and also relieved that we were fans.

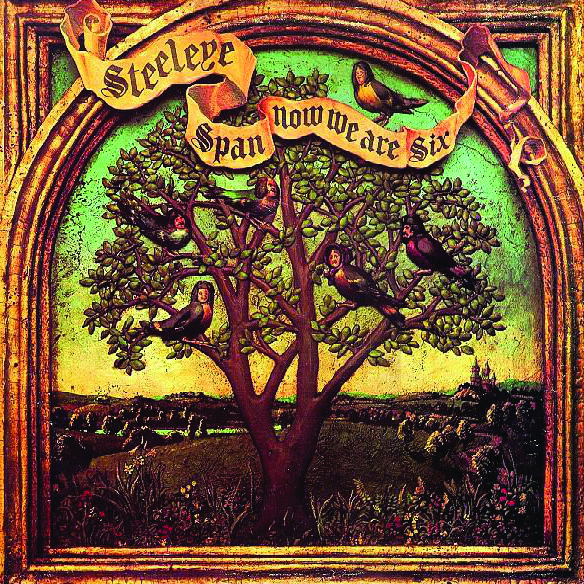

How did David Bowie get collared for his contribution to Now We Are Six?

Rick [Kemp] had been in a band with Mick Ronson in Hull and he asked if they were around while we were recording. He said yes, so Ian Anderson got in touch with him, as he was producing the record. That was a good day in the studio – however when Ian set Bowie off to play this blistering saxophone solo he hadn’t pressed the record button, so we had to ask him to do it again!

You were label-mates with Tull, weren’t you?

That’s right. We joined in 1972 and were the first band to be signed to Chrysalis who they didn’t manage. Tull were on the label and they put us on tour with them. We did five nights in America at the LA Forum – 18,000 people a night. I was terrified the whole time. My mum said, “I don’t know why you do it”, but I had to. It was exciting.

What was the reception like for you in the US?

Really good – we’d start with Ian joining us for Lyke-Wake Dirge, where we were all dressed in ribbons, and we had Mummers onstage with us.

Did the Americans understand it?

No, they didn’t [laughs]. Jethro Tull were also doing Monty Python sketches and had these long idiosyncratic asides. There were no rules, there was no one way to do things then.

Britain joined the European Economic Community in ’73 and an 11-day festival celebrated the fact. You played a night, the Fanfare For Europe Gala. What do you remember about that?

It was at the Albert Hall and [then-Prime Minister] Edward Heath was there and we shook hands. It was a good gig, but in society there was a hoo-ha about ‘Were we going to become unBritish?’ and ideas like that. And now the opposite has happened [with Brexit].

You’ve had a varied career outside of Steeleye; you collaborated with June Tabor, sung with Jethro Tull, Mike Oldfield and Status Quo… is there anyone you’d like to work with in future?

I’ll collaborate with anyone [laughs]! It’s always more scary than working with Steeleye, though. I did something with Nancy Kerr and James Fagan at Cambridge Folk Festival, and sang with Richard Thompson at his 70th, but I tread that line between being terrified and being thrilled by it. Long may that continue.

It’s more than 50 years since Steeleye formed. How does that feel?

When we started we didn’t even know we were going to live for 50 years, never mind being in a band for that time. I never planned anything. I always considered that we staggered from song to song, but Bob had a way of planning things conceptually. Our early years went very fast – our contract was 10 albums in five years. We rehearsed at the Irish Club in Eton Square, then a place called The Black Hole, which describes it perfectly. We became somewhat cavalier with the recording process – there are some things on albums that we regret. We’d run out of ideas. We’d have four or five good songs then we’d have to pull something together like The Drunkard. It would have been better if we had concertina’d a few together.

With Est’d 1969 you were reunited with Ian Anderson and it’s the first time he’d played on a Steeleye album.

And he did a beautiful job, and for free [laughs]. This goes back to Now We Are Six and that David Bowie didn’t ask for a fee. Ian told me about a time he met David again, playing a TV show. He knocked on David’s dressing-room door and said, “Hello, we did that Steeleye Span thing. The one thing I took away from that is that you didn’t charge for that cameo performance. I’ve taken that to heart, I don’t ask for money for cameo performances.” And Bowie shot him a look and said, “Didn’t I get paid?!” And then he smiled, he was just winding him up…

What’s the position of Steeleye as a band today?

I think about Steeleye as a family firm these days. It’s got that quality. Benji’s the son of our friend and former member Jon Kirkpatrick, and he’s worked with Bellowhead so he knows the genre well. Liam [Genockey]’s been in the band for 30 years, and Julian [Litmann]’s been in it a good while but we had to find a way of bringing the others in. As a seven-piece, it’s really rocking. We want to maintain the tune, but we try and fill the room with noise. I do like it loud.

This article originally appeared in issue 127 of Prog Magazine.