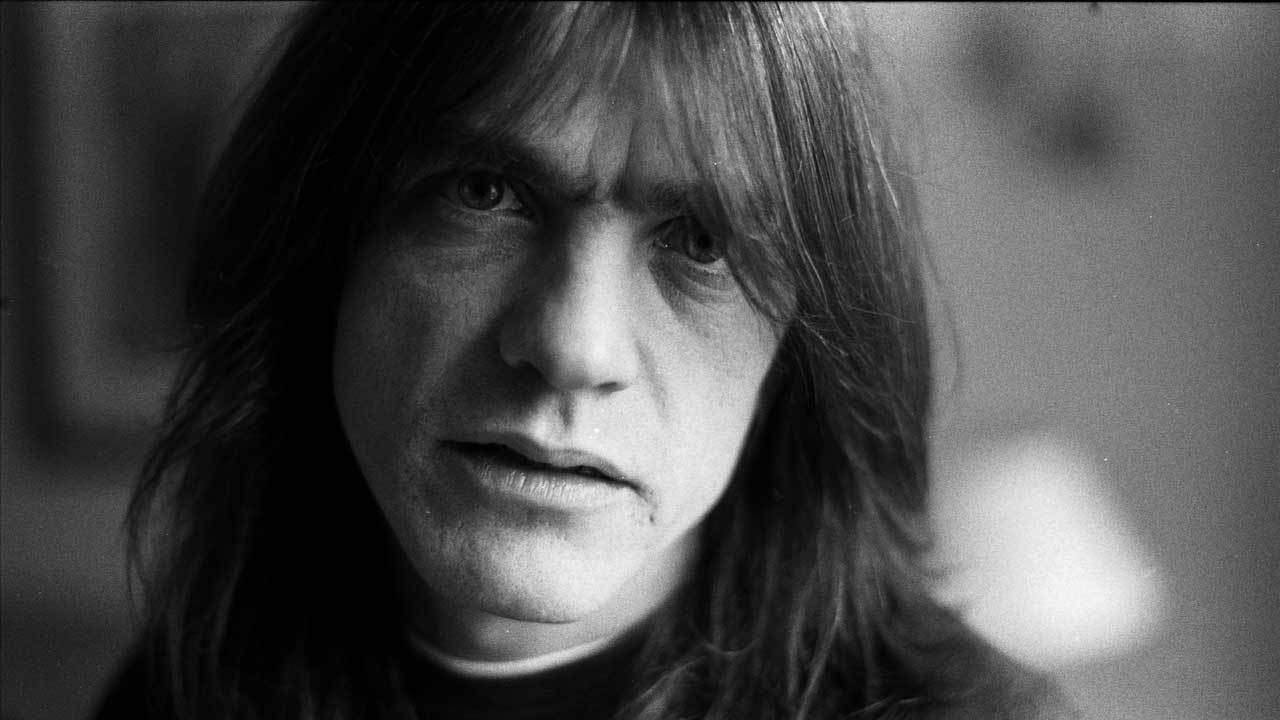

Just like the music made by his band, Malcolm Young spent his 64 years on this planet defiantly opposing all forms of overstatement and grandiosity. Young may have been one of the biggest rock stars that the world has ever seen, but he was proud of being ordinary. He also believed in speaking the truth, no matter who it offended.

Malcolm’s brother Angus, talking to Classic Rock in 2003 several months after AC/DC’s induction to the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, voiced indignation that the HOF had tried – and failed – to “make us wear fucking tuxedos” to the ceremony, adding a curt: “Fuck that!”

Mal, the elder of the two siblings, then took up the story, explaining his band’s annoyance as they were kept waiting around in the wings while U2 guitarist The Edge inducted The Clash.“Fuck, he made this forty-minute speech [about late guitarist Joe Strummer]. We had sympathy [for the Clash], but The Edge was the most boring bloke I’ve ever had the misfortune to witness,” he seethed.

AC/DC got “madder and madder”, until finally their moment arrived. “When they said to go, we fuckin’ took off,” Malcolm said with a grin. “It was an anger-fuelled performance. We ripped the place apart; they were dancing up in the balconies in their tuxes. It was quite a moment for us. The rest of the bands were pretty mild by comparison.”

With its overtones of rebelling at authority, the earning of new-found respect and blowing the doors off in response to a pressure cooker-like scenario, the Hall Of Fame incident could be viewed as a microcosm of the career of this remarkable band. For 45 years AC/DC have personified the words ‘stubborn’, ‘independent’ and ‘secretive’, doing things their way or not doing them at all. With the band having been shortlisted and ignored more than once before by the Hall Of Fame, Malcolm later shrugged: “To us [being inducted] is not really an honour. We just had to go through with it, in a way.”

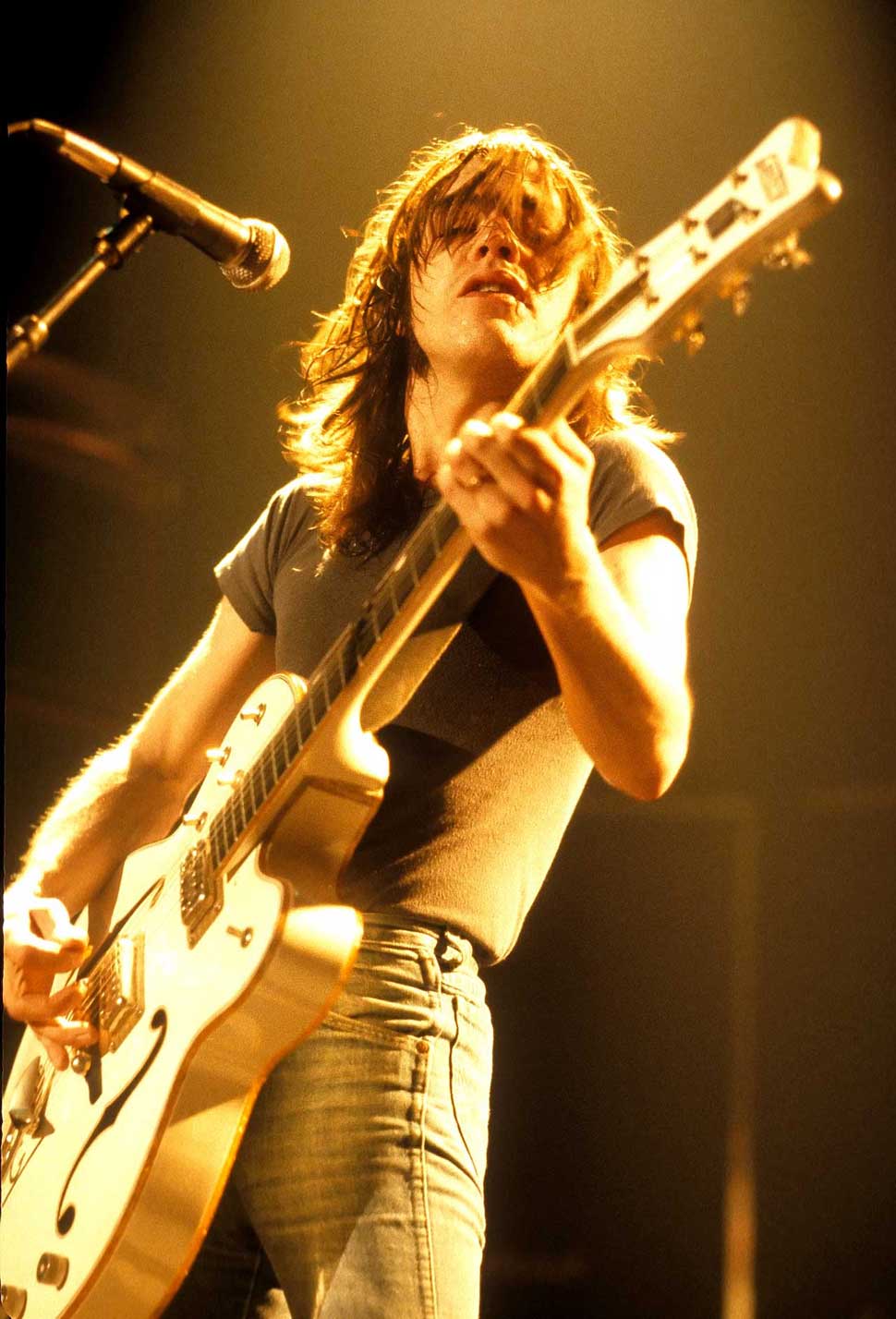

Although several of the group’s members past and present, including lead guitarist Angus and singers Bon Scott and Brian Johnson, are more famous in a visual sense, behind the scenes rhythm guitarist Malcolm was very much the glue that held everything together for AC/DC, co-writing the songs and performing them on stage in a blur of vigour and ease. Malcolm was very much the band’s leader, cracking the whip and ensuring that the AC/DC machine functioned exactly as it needed to.

The world of rock music mourned when Malcolm, who had suffered from dementia for the previous three years, died peacefully surrounded by his family on November 18, 2017.

A statement issued on behalf of AC/DC reminded us of his many qualities: “From the outset, Malcolm knew what he wanted to achieve and, along with his younger brother [Angus], took to the world stage giving their all at every show. Nothing less would do for their fans.” It continued: “Malcolm always stuck to his guns and did and said exactly what he wanted,” it continued. “He took in great pride in all that he endeavoured. His loyalty to the fans was unsurpassed. He leaves behind an enormous legacy that will live on forever.”

Malcolm’s passing came just three weeks after the sudden loss of George, the eldest of the Young brothers and the producer who helped to shape many of AC/DC’s best-loved albums, including High Voltage, TNT, Let There Be Rock and Powerage.

It has always been stressed that Malcolm had given AC/DC his blessing for the band to continue in his absence. In fact they had proved on more than one occasion that it was possible to tour without him, first in 1988 when nephew Stevie deputised as Malcolm dealt with alcohol issues, then in a more permanent manner in 2014, and also that the band could record while deprived of his creative input. The problem the group now face is whether or not it would be right to do so.

Notwithstanding the hearing problems that forced Brian Johnson to sit out much of AC/DC’s most recent tour, on which Guns N’ Roses’ Axl Rose stood in, could AC/DC have now reached the end of the road? That’s a question for another day, but the odds must surely be weighted in favour of a dignified final resolution?

Malcolm Mitchell Young was born on a council estate in the Cranhill district of Glasgow. Of distinctly blue-collar stock, his father worked in a rope works, at a builders’ yard and then after the war as a postman, while his mother remained at home to nurture a clan that included eight children.

Along with another 13 members of the Young family, Malcolm and Angus emigrated to Australia in the summer of 1963. If the brothers were not already close enough, being the two kids with ‘funny accents’ in a foreign land served to bond them even more.

As every rock fan knows, a decade later AC/DC were formed and shaped within Sydney’s super-tough bar circuit – an environment that could strike fear into the toughest of alpha males, let alone a band with a name that could be seen as implying bisexuality. In fact the name supposedly came after Angus and Malcolm’s sister Margaret had seen the letters on a sewing machine.

George was the first of the brothers to find stardom, having formed The Easybeats with Harry Vanda and in 1966 had an international hit with Friday On My Mind.

“Me and Angus were playing guitar already, even before we left Glasgow,” Malcolm recalled decades later. “By [George] doing well [with The Easybeats], you sort of quietly dreamed that you could do it too, one day.”

Although AC/DC’s style has often been categorised as hard rock or even heavy metal, Malcolm later stressed: “From the get-go I said it was a rock’n’roll band. That’s how it evolved. I was still playing guitar like a piano to get a vibe of a Little Richard song, so it was things like that, playing rhythm around where the rhythm came from on the record, but with two guitars.”

The decision to promote Bon Scott from band ‘chauffeur’ to lead singer in 1974 was to prove pivotal. Not unreasonably, Angus thought Malcolm and Margaret were taking the piss when, that same year, they first suggested that Angus should dress up as a schoolboy on stage. But this unlikely gamble actually achieved its intended goal by defusing the violence.

As Vanda & Young, Harry Vanda and George Young took on the role of the band’s producers. AC/DC’s first two Australia-released albums (later pared down for the international market as High Voltage) showed greatness in fits and starts.

Relocating to London in 1976, where they had signed an international deal, the band once again built their reputation from scratch, going from playing venues such as the Red Cow pub in Hammersmith, West London, where they debuted, to setting new attendance records at the Marquee club in Wardour Street.

The albums Let There Be Rock and Powerage, issued in 1977 and ’78 respectively, stand as irresistible watermarks of this period. But the band’s big breakthrough came after linking up with producer Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange for Highway To Hell. Malcolm later admitted that they had no idea of Lange’s history, joking: “If we’d known that he had produced the Boomtown Rats we’d never have let him through the door.” All that they knew was their manager Michael Browning’s verdict that the South African was “a genius”. And so it proved.

After Bon Scott’s tragic sudden death in February 1980, AC/DC considered calling it a day. But instead they picked up the pieces – with what might have seemed to some like indecent haste – and released their next album, recorded with his replacement, former Geordie singer Brian Johnson, five months later.

Back In Black, produced by Mutt Lange, made AC/DC bigger than ever before, its eventual 50 million sales (and counting) making it the second-biggest-selling album ever, behind Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

Follow-up For Those About To Rock We Salute You, however, was patchy by comparison. Years later Malcolm exclaimed: “Christ, it took forever to make that record – and it sounds like it. It’s full of bits and pieces and it doesn’t flow properly. There’s some good riffs, but only one song we like and that’s the title track.” Despite its shortcomings, it still topped the US chart.

Although it would take a while, the band’s fortunes began to dip. The lacklustre Flick Of The Switch (’83) just managed platinum status, while next album, Fly On The Wall (’85), fared even worse.

While in the face of dwindling returns and popularity some groups might have taken a long, hard look at themselves and decided a change or two was needed, AC/DC continued to plough the same familiar hi-decibel, double entendre-enhanced furrow they had always done and on which they had built their reputation and greatest successes.

When their headline appearance at Castle Donington’s Monsters Of Rock Festival in 1984 was dismissed as “stale”, Malcolm, talking to one interviewer from Kerrang!, bristled: “There’s no reason to change our act – and it’s not really an act, that’s the way Angus is. He likes to run around and take it out on his guitar. Look,” he added, “we don’t make music for the critics, we go for the reaction from the kids. If they stopped reacting, then we’d know something was wrong. But at Donington everybody in the place was rocking. If anybody criticised that, then they weren’t at the show.”

Sure enough, things came around again. The patronage of new stars such as Guns N’ Roses and Metallica didn’t hurt them at all.

Along the way, Malcolm stepped off the band’s touring schedule to get sober. “The funny thing was I was never drunk heaps, I just drank consistently and it caught up with me,” he admitted in 2004. “Angus was going: ‘I’m your brother; I don’t want to see you dead here. Remember Bon?’ So I took that break and cleaned myself up.”

Having re-engaged Vanda & Young for 1988’s Blow Up Your Video, two years later they were accused of selling out by bringing in producer Bruce Fairbairn, of Bon Jovi/Aerosmith fame, for The Razors Edge. The album made the US and UK Top 10 and sold an estimated 10 million copies.

By the 1990s, hair metal had been supplanted by the grunge revolution, and as an act founded upon pure rock’n’roll AC/DC were cast as outsiders once again. In ’92, an interviewer asked Malcolm which bands he’d listened to while growing up. The answer – “The Stones and The Who” – was about as unsurprising as his response to then being asked who he currently listened to: “The Stones and The Who… and that’s about it.”

AC/DC’s reputation as a premier-league live attraction remained undiminished, however. That decade they released just one more studio album, the Rick Rubin-produced Ballbreaker. “We would never go back to him,” Malcolm told Guitar World of Grammy winner Rubin, who would develop a reputation for reviving the careers of artists on the wane. “We thought he was a phony.”

Sure enough, later on AC/DC returned to brother George (without Harry Vanda) for their first record of the current millennium. 2000’s Stiff Upper Lip attained Top 10 status effortlessly in America, but by now the band’s golden era was already behind them.

No matter what yardstick you use, AC/DC’s achievements were huge. Over a career that brought them an estimated 200 million record sales, Angus and Malcolm stuck to the adage ‘if it ain’t broke don’t fix it’ and together they cannily – some might say ruthlessly – planned a route to the very top.

Few bands would have had the balls to fire Peter Mensch, their manager, five days after they had played at the Monsters Of Rock Festival in 1981, although according to tour manager Ian Jeffrey – himself later frozen out (“It was like I never existed”) – that’s exactly what the Youngs did. More surprising still was the decision to say goodbye to ‘Mutt’ Lange, the mastermind behind their game-changing breakthrough Back In Black. Angus later complained: “He’d take forever to get things done. Otherwise it’d have been in and out in a week, I’d say.”

The man behind so many of these important decisions was Malcolm Young. “The band belonged to Malcolm,” Ian Jeffrey once claimed. “It was Malcolm who told [drummer] Phil Rudd to stick to the beat; Malcolm who told [bassist] Cliff [Williams] where to stand, when to come to the mic. When Brian [Johnson] joined, it was Malcolm who told him to shut the fuck up between songs and just stand there and sing. It would always be Malcolm, every direction or turning they took.”

If decisions needed to be merciless, then they were. And it’s difficult to view Brian Johnson’s removal from the group in 2016 as anything but that, although it had nothing to do with Malcolm, who was already sick. But over the long term, such ruthlessness was certainly part of the fuel that fired AC/DC to world domination.

The final album AC/DC made with Malcolm Young, Black Ice, topped the charts in 29 countries. Out on the road and with his memory beginning to fade, before each show Malcolm had to sit down and brush up on the small details of the performance.

“It was hard work for him,” Angus told The Guardian’s Michael Hann. “He was relearning a lot of those songs that he knew backwards; the ones we were playing that night he’d be relearning. He had that thing where you’ve just got to keep going.”

Naturally there were both highs and lows.

“You’d have a really great day and he’d be Malcolm again, and other times his mind was going,” Angus revealed. “But he still held it together. He’d still get on the stage. Some nights he played and you’d think: ‘Does he know where he is?’ But he got through.”

The brothers had had the difficult conversation about Mal’s failing health even before work on Black Ice began. Angus revealed: “I had said to him: ‘Are you sure you want to do this? I have to know that you really want to do it.’ He was the one who said: ‘Yes! We’ve really got to do it.’”

The inevitable point was reached at which Malcolm could no longer be a part of AC/DC. Since 2014 he had been receiving around-the-clock care while living in a nursing home. Understandably and rightly, the band were furious when the Sydney Morning Herald revealed the full extent of his condition. “That was bottom-feeding, that was,” Brian Johnson says.

For Angus, without his elder brother on board and by his side it was, of course, distinctly troubling to continue touring the world and pretend it was business as usual. But he knuckled down. And even when Johnson was unable to tour Rock Or Bust the show went on. It was a mark of AC/DC’s stature that Axl Rose agreed to help them out by standing in for Johnson; as was Rose’s unexpected raised levels of professionalism when he shoehorned himself into their highly regimented world without displaying the tardiness for which he has been strongly criticised.

With Rose in tow the Rock Or Bust tour generated a whopping $67.5 million (£50m) in 2016, placing AC/DC at the top that year’s list of the biggest earners in rock, ahead of the Stones, Bruce Springsteen, Paul McCartney and U2. While the importance of fulfilling their planned obligations cannot be overstated, for Angus and others involved with AC/DC, many years had passed since money could be considered a driving force.

A veritable Who’s Who of Australian rock music gathered for Malcom’s funeral at St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney, among them bandmates past and present including Brian Johnson, Phil Rudd, Cliff Williams and Mark Evans, and Angry Anderson, Jimmy Barnes and Harry Vanda. At the ceremony, Angus defiantly wore a pair of jeans and clutched his brother’s beloved Gretsch Jet Firebird guitar, nicknamed The Beast, in its case. During the service, he reportedly rested the prized instrument on his brother’s coffin.

Members of the Young family and AC/DC alumni did not take to the lectern. And although Malcolm had made a living via the bawdiest and ballsiest of rock songs, he was sent on his final journey by a cathedral choir that sang the hymns Amazing Grace and The Lord is My Shepherd. After the service, as the cortege drew away to a private family burial, the Scots College Pipes & Drums Band played a medley of songs including Waltzing Matilda and the guitar solo from It’s A Long Way To The Top. It was a dignified end to an extraordinary life.

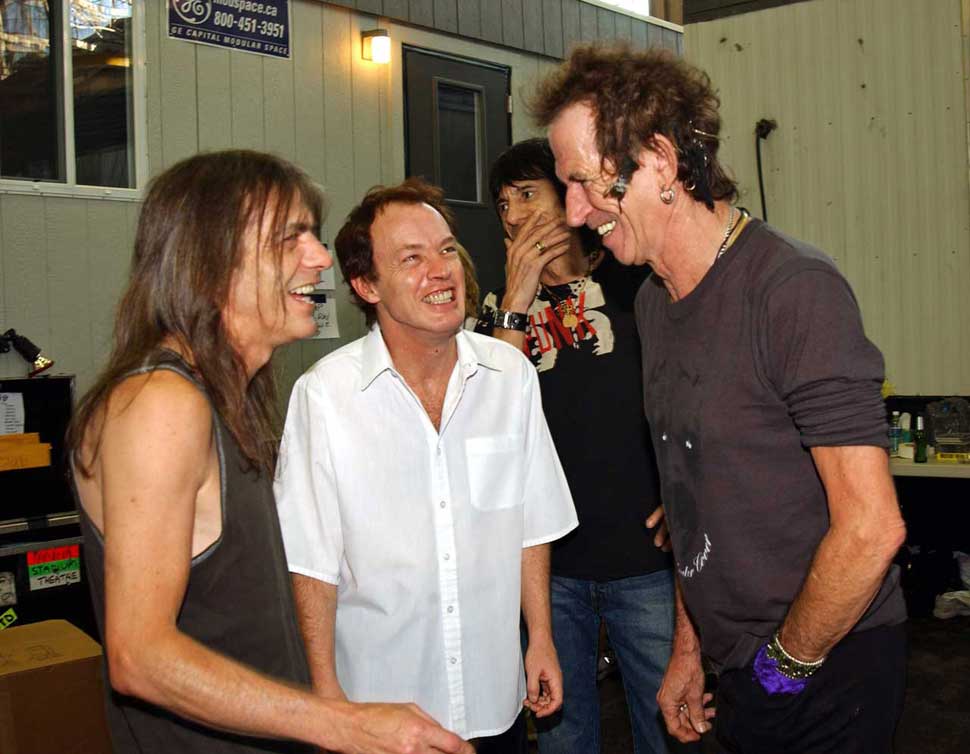

I had been thrilled to interview Malcolm and Angus together for Classic Rock in Berlin in 2003. They were exactly like you imagined: foul-mouthed and blokey as fuck, tiny in stature (each stood less than five foot five) but huge in presence. Angus chain-smoked with unbelievable regularity, lighting another ciggie even before he’d finished the one he was already puffing on. Malcolm was blunt, friendly and unflinchingly honest.

AC/DC were in Germany to play three shows with their heroes the Rolling Stones, with whom they’d jammed in Australia the previous year. “I think we could be making music when we’re as old as them,” Malcolm told me. “From the beginning, this band always went for the throat. It was an energy thing, and it still is.”

Sheer unadulterated volume has always played a part too. After Angus quipped: “That’s to keep you awake,” Malcolm sat upright in the chair and declared: “We’re not going to fall into that trap of old age. We can’t get up there and play Highway To Hell, For Those About To Rock and The Jack quietly.” That last word was expressed with disdain. “You gotta stay young.”

When I asked whether they sometimes thought Bon Scott might be looking down – or up! – on AC/DC’s success since he passed away, Mal grinned: “To be honest, if there is an afterlife he’ll probably be saying: ‘C’mon, guys. Play that one fucking faster, put some fucking grunt into it.’ That’s what he was like.

“When he joined us, Bon took the band by the scruff of the neck,” he continued. “On stage it’d be: ‘Don’t just stand there, you c**t.’ So whatever AC/DC went on to achieve, Bon was also very responsible for.”

The last words, inevitably, go to Angus: “The bond that we had was unique and very special. My brother leaves behind an enormous legacy that will live on for ever. Malcolm, job well done.”

Just like his friend Bon Scott, Malcolm Young put ‘grunt’ into everything that he did. Like the singer he, too, will be sorely missed.