There’s a moment on the DVD released with the 10th anniversary reissue of the Manic Street Preachers’ Everything Must Go, album where frontman James Dean Bradfield is caught in silhouette wandering around a nearly empty and quite cavernous Nynex arena one afternoon in May 1997. He’s accompanied by the usual call-and-return of a road crew soundchecking, the clack and thrum of flight cases being wheeled through the expansive venue, a bass drum being kicked into life... It’s a moment shortly before the Manic Street Preachers’ then biggest headlining show to date: a 17,000-seater sell-out that had people camping outside the Manchester venue’s doors through the night. As much as you can elicit from Bradfield’s body language – hands in pockets, head down – he looks more like a young boy looking for a stone to kick than the lead singer with a band finally rising at an accelerating commercial rate.

The clip cuts to an ill-at-ease-looking band sitting around on rickety chairs, being interviewed about a year of triumphs crystallised by the mammoth Nynex gig. Drummer Sean Moore is nonchalance personified, bassist Nicky Wire recalls past glories and then is lost in the moment of reverie. Bradfield admits to getting very drunk that night and not much more. Wire baits him a little about his inability to celebrate their successes, then they have what can only be described as a bit of an argument. It seems an odd [yet inordinately Manic] way to express their feelings for the culmination of what really was a very good year.

“I think James gets more pleasure from when he’s smoking and drinking and making music than those sort of things,” says Nicky Wire today, stretching out on the sofa in the band’s management office in west London. “We won two Brits and six NME awards, and James threw one of them back at Mark and Lard [in his defence, it was for Best Song With Kevin In The Title]; he almost brained them…”

He rubs his jaw gingerly, tentatively checking recent root canal work. “It was much the same when we got our first No.1 single with If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next. The label had organised this huge party with champagne, and James staggered down into the hotel and all he wanted was Ribena – that’s his hangover drink – and for someone to get him a pastie.”

A week earlier in a rehearsal studio near King’s Cross, and James drinks steadily from a corrugated cup of coffee; not a pastie or carton of Ribena in sight, so it’s no surprise that he’s alert. On the table between us are copies of the Manics’ Greatest Hits CD and The Clash’s London Calling. It’s a few days before the final leg of his tour to support his solo album The Great Western, and both bands’ songs will appear in his live set.

“I always had this thing that when success finally came to us – proper, mainstream success – one little bit of bitterness always stopped me celebrating the fact that we were getting what I thought we deserved all along,” he admits when I mention what passes for his indifference to the phenomenal success that finally came with their fourth album. “I thought Motorcyle Emptiness deserved to be a no.1 single. La Tristesse Durena [Scream To A Sigh], that should have at least been a Top 10 hit. It was fucking 27 or something. S,o, when these things did start coming to us, I was just thinking. ‘It’s about fucking time’. That little bit of rancour and bitterness just stopped me going: ‘Yeah, we did it!’. I’m probably a tiny bit more ambitious and a little more bitter about it than people would actually suspect, I suppose.”

Conventional thinking had written off the Manics after the relatively poor sales of The Holy Bible, and the disappearance of their guitarist Richey Edwards in February 1995. Once the Kohl-covered, panda-eyed darlings of the press, they had become austere and remote [it was said], fractured by the death of former manager Philip Hall [remembered fondly on James’s single An English Gentleman] and Richey’s increasingly erratic moods. Sales figures and a Reading festival appearance without the wayward guitarist aside, a lot of what was being said about them was conjecture. But people loved to theorise about the Manics. They were that kind of band.

When the Manics had originally gone to their record company with the songs for their debut, Generation Terrorists, the label, to paraphrase Tom Petty, didn’t hear a single. To that end they sent them off to a pile in the English countryside called House In The Woods. It’s a place they would return to again and again.

“It’s down in Surrey somewhere. You sort of come upon it in this clearing,” says James, crossing the rehearsal room to turn off an amplifier that’s buzzing like an irate bluebottle. “We went down there initially with producer Steve Brown and we finished Motorcycle Emptiness there and Little Baby Nothing, and then we went back there for the Gold Against The Soul record too. Then back there for what would become Everything Must Go. But by the time we’d gone back there after The Holy Bible it was becoming obvious that Richey had been through quite a lot in the interim, and when we were there it just felt like something was breaking, slowly but surely. He was better, definitely, but now what we realise is that it was the calm before the storm. Looking back, he’d decided what he was going to do and he was calmer and happier, but he was trying not to drink and not staying in bed most of the day. He was kind of strangely happy.”

“It was a fantastic place. You’d imagine the Stones would have recorded there,” recalls Nicky. “They had this basement, and you’d go and bash out a few bits and then have a gin and tonic. And the last time was great. But, you know, I don’t think it’s tainted for me. I know it has for James, but I’m glad a phase ended like that instead of the ongoing shit that we’d be going through as a band. In his own way I think it was Richey making some sort of peace with us. It’s the strangest period we ever had as a band; it had been pretty unpredictable to say the least. It’d been verging on the fucking miserable, but for those two weeks something had clicked in him. Whether he knew what he was going to do or he felt the freedom from it, I don’t know, but he was just bang on form, just like he always was. We thought, ‘This is great’. But obviously, having done a bit of research, that moment of euphoria before either suicide or disappearance does seem to be applicable to a lot of people – when you’ve actually made the decision that you’re taking control.

“We did a lot of work there, too: we did a demo for Small Black Flowers That Grow In The Sky, which is fantastic; we did No Surface All Feeling – 30 or 40 per cent of it is actually on the finished version; James did Kevin Carter, which he played to Richey as an acoustic thing – he didn’t record it, but he wrote it; and Further Away. So we did a lot of stuff. We were only there for about 10 days.

“Me and Sean went home from there, and James drove Richey to London. We’d just bought a band car, the Vauxhall Cavalier [the car that was later found abandoned by the Severn Bridge], and the ashtray in it was like the mountain in Close Encounters… It was terrible. Sean hated it and I hated it because we’re anti-smokers. And it was only three months old. So James and Richey drove the Cavalier to the Embassy Hotel and that was it. I remember them leaving, and it was one of those dark, dark nights. And that was the end, really.”

“We left there with some songs in our pockets,” says James, “And we pulled into the car park underneath the hotel. We’d just finished playing the demos and I asked Richey which his favourite was. He went: ‘I suppose the one I really like is Small Black Flowers That Grow In The Sky’. I thought it might be because I knew where his head was at that time, or I thought I did. So when it came to doing that one I wanted it to fulfil what he liked about the song, I wanted it to be very bare and emotional. It’s odd to think now how gloriously idyllic House In The Woods was, but with the events that took over it’s turned into a bit of a spectre for me. It was very creative there and had a lot of happy memories, but now it’s something else, you know. We left that day, drove up to the Embassy, checked in and the next morning that’s when Richey wasn’t there in the lobby to meet me.”

Richey left behind a mountain of theories and a handful of lyrics. He also left behind three friends filled with disquiet and heartbreak. The occasional idiot in the press suggested that the very soul of the band had gone now that their prettiest member had disappeared into the ether, but in truth the Manics had begun as a trio and were about to revert to type. As well as the material the band had worked up at House In The Woods, Nicky was working on two sets of lyrics, both dealing, to a greater or lesser degree, with the working classes, one focusing on the Welsh working class especially. The former was called Pure Motive, the latter A Design For Life.

“Pure Motive was really influenced by Cracker, as I remember – the episode To Be A Somebody with Robert Carlyle,” says Nicky. “It was that and it was a reaction to the way Blur had hijacked the working-class thing in an ironic way – the whole greyhound racing, flat cap thing; unbelievably patronising. And then you had Oasis, who I loved, but who kind of showed the thick-as-shit side. It was those two polarising things, and I just thought this is a bad representation of the way I was brought up… I didn’t mind that James had taken two songs and made them one either, as I found the originals the other day and there’s so much shit on them. I can’t believe how naïve some of them are.”

“He gave me these two sets of lyrics,” James recalls. “And one was sort of based on this idea, this misconception of working-class culture in general, and then A Design For Life was a sort of celebration of it. I put the two together, it seemed really natural. I remember calling Nick on the phone to play him the song and being the most excited I’d been in a long time.”

“He seemed ultra-confident,” says Nicky, “which after the last 12 months was something. He’d never sang Faster [from The Holy Bible] down the phone to me, put it that way. There was something about A Design For Life. It was the way he could visualise all the parts. He just couldn’t have done that with Richey around, because there were certain caveats with Richey: would there be a certain sample at the beginning on the song, there would be some odd chorus. But it was so succinct and so well-formed in his head that I could tell he was on to something. After A Design For Life, I knew we could make our way back.”

The band decamped to Chateau De La Rouge Motte in France as the winter of 1995 approached. The Chateau doubled as home and studio for producer Mike Hedges [The Cure, Siouxsie & The Banshees, Everything But The Girl]. The band had tried to enlist him for The Holy Bible, but a hectic schedule meant he wouldn’t be able to work with the band until that autumn. With a sound desk from Abbey Road Studios that had once been used on the sessions for Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon, and a snowy location in the French countryside, the band got to work on the album that would become Everything Must Go.

“The first thing we did when we got there was our cover of Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head for the Warchild charity album”, says James. “It was brilliant, it was a good little confidence builder for the rest of the session. We would never have made as good an album if we hadn’t been in that environment, if we hadn’t felt so shut away, those dark winter nights with a roaring fire, food on the table, lots of wine, walking in the countryside… It was just like being in Wales but not knowing anybody and having slightly better food.”

Richey’s contribution to the album came with co- writing credits on Elvis Impersonator: Blackpool Pier, The Girl Who Wanted To Be God, Small Black Flowers That Grow In The Sky and Kevin Carter. Even though he was developing as a writer, it’s difficult to imagine his dense, sometime brilliant lyrics sitting easily alongside some of the material on Everything Must Go. It’s as weighty in its endeavour and scope, but the barren, internalised themes permeating The Holy Bible are less evident here.

“People have often debated whether Richey would have liked Everything Must Go,” says Nicky. “Would he have wanted it to go that way? But at the end of the day, James is the dominating musical influence, so it would have been what it would have been. There might have been a bit more weirdness in there, but I don’t think it would have been so far from the album people know.

“And sometimes I think Richey wouldn’t have liked it. But there’s always that thing: he did love the glamour of being big. He might not have liked it that much, but he would have liked the results, he would have enjoyed that.”

“I remember getting the lyrics to Revol [The Holy Bible] and thinking this is a song about the sexual peccadillos of notorious dictators and how those sexual peccadillos can mutate into abuse of power. Right, write a song,” says James, still looking perplexed by the memory. “But I’ve got to say that’s the strange kind of irony: that at the point before he disappeared, Richey was writing about stuff like that with a bit more clarity, things like Small Black Flowers… and especially Kevin Carter and Elvis Impersonator… He’d evolved into writing about these things a bit more clearly, a bit more concisely. That’s the bitter-sweet notion: that Nick and Richey could have been such a brilliant lyrical partnership. They proved to be on Everything Must Go; Elvis Impersonator… is a good 50⁄50 job. So that’s the bitter-sweet side of it.”

Mark Morrison’s Return Of The Mack would keep A Design For Life from the top of the singles chart, but by the time it was scaling the Top 40 Everything Must Go was selling at a rate of roughly 50,000 albums a week. The band had stripped back their artifice and glamour, focusing on the idea that the music should speak for itself, that everything else really did have to go. They came blinking back into the limelight supporting The Stone Roses at Wembley. By his own admission James was dressed like Man At C&A, while Nicky, although struggling with the idea, turned up in a hockey top. By time they headlined the Reading festival, Wire was back in eyeliner and a sheer dress [“I couldn’t help myself”].

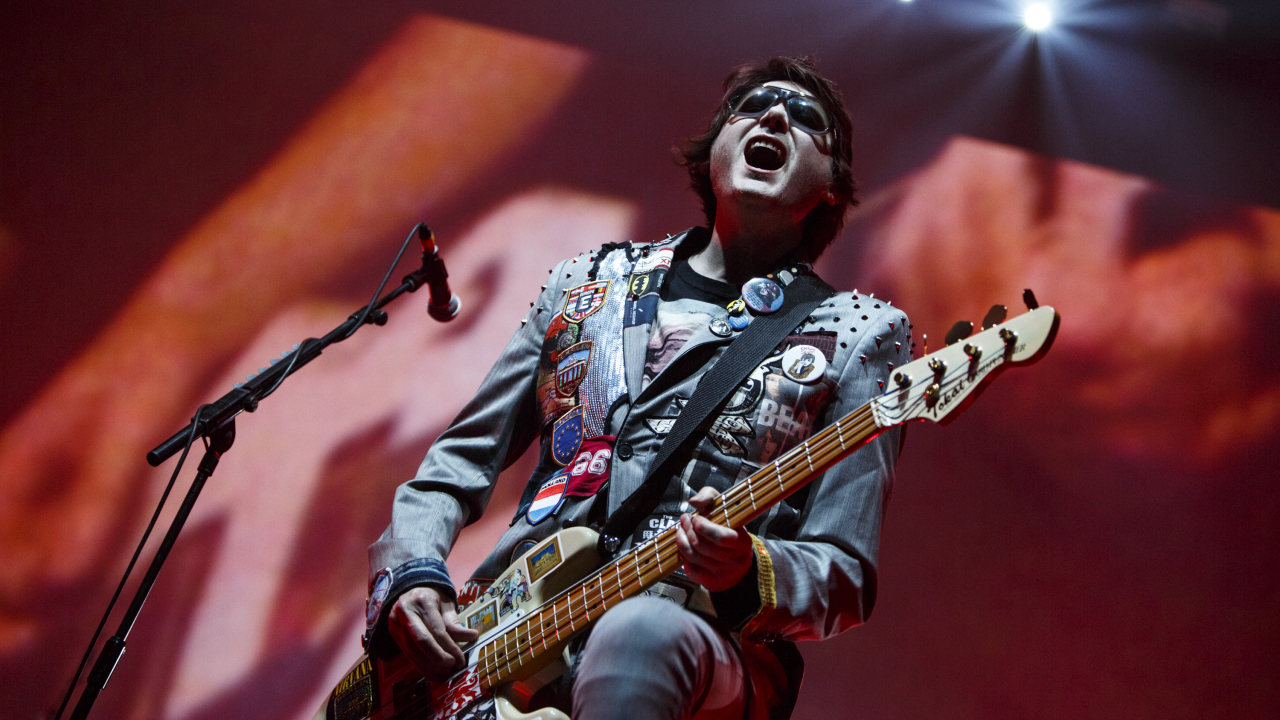

The Manics were inventive and important – and this after most critics had written them off after their so-called heart and soul had apparently disappeared along the banks of the River Severn. Like the silhouette of James padding around the Nynex Arena, there’s another enduring image on the Everything Must Go DVD: the band’s first performance on Later…With Jools Holland. With a year of shows behind them and with a point to prove [the show’s producers had refused to book them before Everything Must Go], they tear through Australia at a fierce pace. Sean looks like a young Keith Moon flailing away, while James and Nicky share a satisfied smile. It’s just a glance between the both of them. A happy, contented look. But its significance shouldn’t be underestimated. Nicky calls the 12 months after the release of Everything Must Go “the year the Manic Street Preachers were loved”.

“We felt we were doing something good and getting an amazing amount of love for it,” he recalls fondly. “People were buying our records. And we’ve never been afraid to say that we wanted to be huge, you know. We doubled our live audiences. And then giving my mum and dad a disc that said: ‘1.5 million albums sold…’.”

“It was hard when people were pitching us against the memory of a friend [Richey],” says James. “It was a brilliant chemistry we had, but we still think we had something to offer. And when we realised we could be a different version of the Manics without Richey, and musically be a better band, it was such a relief and that’s perhaps why sometimes we do look so happy. And winning the two Brits and taking them home to my mum and dad. That was brilliant. She was really happy because they’d been playing a Manics thing in either Corrie or EastEnders. So Brits on the mantelpiece and being played on the TV, she was dead happy – that’s proper success!” There’s a pause and a chuckle. “They were the best sorts of things, definitely.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #101.

For more on the Manics and the time they met and interviewed Rush, then click on the link below.