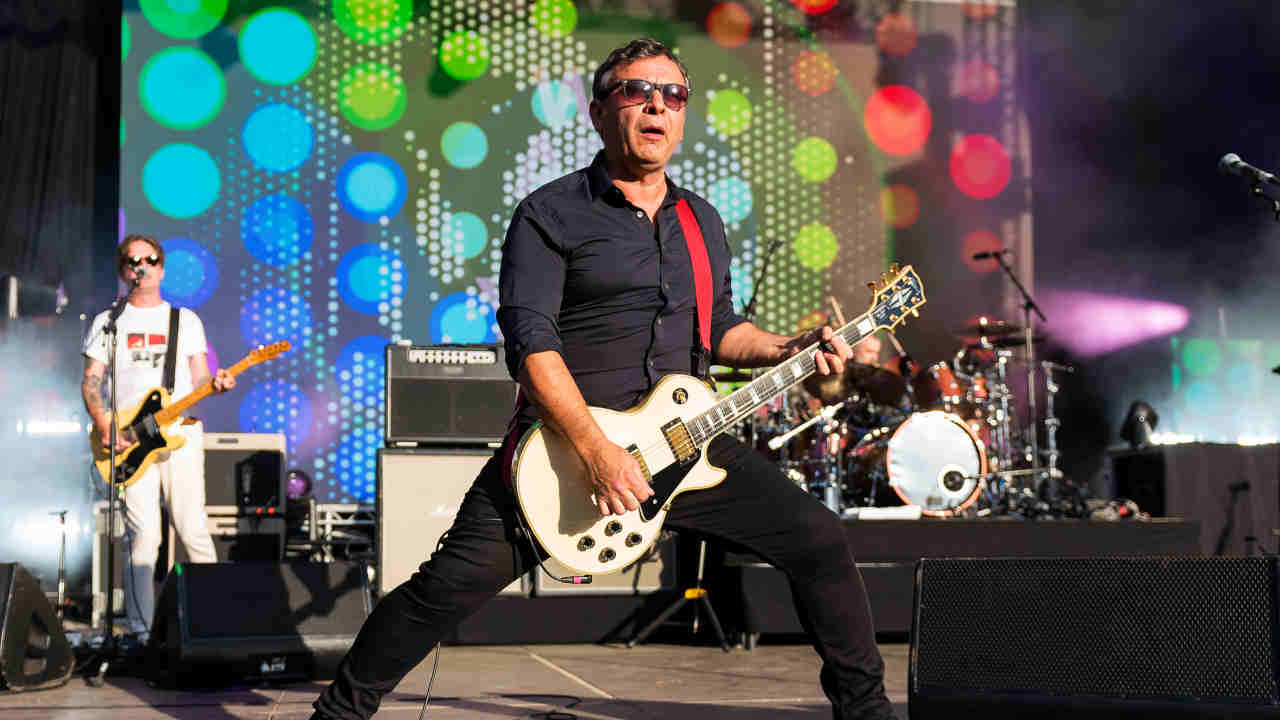

“We’ve done a lot of our growing up in public, made our mistakes too. We’ve suffered at times with that. Our extremes are extreme”: How the Manic Street Preachers shook things up to make new album Critical Thinking

Even after all this time, the Manic Street Preachers still bow to no one

Eighteen miles, give or take. That’s how far it is by road from Cardiff to Newport. Seven years ago, during the recording sessions for what would become their Resistance Is Futile album, the Manic Street Preachers ended their ongoing lease on Faster Studios in the heart of the capital (Nicky Wire: “grimy”) and moved east and bought the Door To The River Studios in Newport. The surrounding area can best be described as bucolic – an adjective we use about a half dozen times over the next few hours as we stare out of the studio’s picture window, through the thicket of ash trees and down to the transporter bridge in the distance. The scene, a Welsh archetype of lush countryside and heavy industry, is framed by a milky-white light that is part hazy sunshine and partly the promise of rain. Welcome to Wales.

The dauntingly large mixing desk, so big it had to come in through the picture window, dominates the room in this former family home-come-rehearsal space and studio. One of Richey Edwards’s old stage jackets sits framed at the top of the stairs. Smaller ante-rooms, once spare bedrooms one assumes, splinter off the main landing, one filled with shelves of drums, literally floor to ceiling, another with a row guitars that curves off around the corner and out of sight. “My few basses are shoved over there in the corner,” sighs Nicky Wire.

James Dean Bradfield is making coffee, and explaining how the desk was brought over from the famed Rockfield Studios and transplanted to a cottage in Caerleon. “A Farewell To Kings,” he says, listing some of the albums that were captured on that mixing desk in its former home. “A little bit of Queen, we believe, and definitely stuff like Graham Parker And The Rumour and Echo And The Bunnymen. We’ve just bought ten grand of parts for it which will see us through, because when stuff breaks in it it’s nearly gone. Like an old Porsche.”

It’s a far cry from their former studio, and given the changing face of the last few Manics albums – the highly polished, harder edged record like Resistance Is Futile (made at Faster and this place), the lilting The Ultra Vivid Lament, and their latest, Critical Thinking, which outwardly and musically is as serene and calming as staring out at the ocean, before realising that below the surface hides a cruel undertow.

“Has our environment seeped into the music?” Bradfield ponders, repeating the question.

“Yeah, I think things are a bit gentler. But that coincides with the age too, doesn’t it? And we were working on those Faster studio songs in 2016, so that’s nearly ten years ago. I don’t know, it may have affected it. I think this window and the view may have affected it, definitely. I do know that I like the isolation, that you can come in and record on your own, and I like that we’re recording in a home. It’s like we’re in Slow Horses or a witness-relocation program.”

He sets the coffee down.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Toffee Crisp, or Wispa?”

“I think the last two in particular, the mixture of doing it here and at Rockfield, there is a calm in both those albums. I don’t know, a calm euphoria at times.”

That’s what Nicky Wire says on the subject of upping sticks and leaving Faster studios for the Welsh countryside. The Manics’ fifteenth album is notable for a few things, not least that it’s bookended with tracks with Wire on lead vocals, and Bradfield has contributed three sets of – very good – lyrics. It might not be reinventing the wheel, but it shows a thirst for ongoing innovation and experimentation only enabled by anytime access to their own studio space. Their in-house engineer, Loz Williams, lives just down the hill, and Wire can drive here in 15 minutes. Which is what he did on the day of the Queen’s funeral. “It wasn’t a big ‘fuck you’,” he says, “I just wanted to avoid it.”

We’re on the first floor of the studio, which is dominated by a giant TV; the Manics watch a lot of sport in their down time. A glass table, on which sit a collage of the handwritten lyrics to Faster, the last remnant of the band’s former home, sits between us.

“So, I came to the studio,” Wire explains, “and all I had was Paul Cook’s drum loop from No Fun as a guide – we never used it in the finished song – not much else, really, and wrote One Man Militia. I played the guitar, bass, used the drum loop, and did all the vocals. And then, obviously, the boys piled in and made it ten times better.”

One Man Militia is a fitting end to an album, although initially it wasn’t intended to be the closer. It’s hard as nails, scathing and funny, dripping with Wire’s ire. It’s one of the earliest tenets of the Manics’ sound: racked with impotent anger. It’s bleakly funny, too, and ends with the band at full bore, crashing around the studio, Sean Moore hammering away at his kit, the band thrashing away at their instruments. It’s a glorious crescendo.

“I love that ending, it’s euphoric. I love what we all brought to it, you know, the first solo is me, you know, the surf one, and I told James to replay it, make it better, basically. He went: ‘Oh no,’ and he was taking the piss, but he went: ‘You’ve got a really good vibrato! Which you can only say after forty years of knowing each other.

“But at first it was about this mantra, rather than trying to write a massive verse and a massive chorus. Just this mantra, which took off. That was a magic moment. It was just me and Loz here, and we resisted building on it too much: ‘Let’s do this fucking choir, let’s put an orchestra here, less Postcards From A Young Man,’ you know? We’ve defragged ourselves in terms of that, undoubtedly. Hiding In Plain Sight is the perfect example where we could have made that bigger and bigger.”

Hiding, the second single from the album, with a Wire vocal and which is somehow saddened, angry and reflective, was written in just 15 minutes.

“I’ve still got that just-off-kilter rage, which I’ve controlled now but it’s still there,” says Wire. “When that goes, I’ll probably just drop dead.”

You enjoy the discomfort?

“Yeah, I need the discomfort. I need hard work and discomfort.”

There’s a real note of regret in the song where you sing about wanting to be in love with the man you used to be, in a decade when you felt free.

“I think most people would think that’s probably the nineties I’m talking about, being in the band and everything being brilliant. Which is all true, but I think it’s more a reference to the unadulterated beauty and innocence of the seventies. A lot of people think the seventies are some derelict fucking era, strikes, steelworks closing down. I’m not saying we were the richest people on earth or anything, but the one thing I’m more grateful for than anything else is growing up where I did with my mum and dad and my brother. It’s just a fucking fluke of wonderment. I think there’s no consequences when you’re a child like that. Even when you’re a big band later in life and things are going amazingly well, and having your own kids, there are so many amazing things, but there’s always a consequence. Good and bad. But when you’re at that point in my life, there were no consequences, it was just watching the telly, playing football, running everywhere. Days at the beach, endless skies, innocence.”

“I still think about the single first, I’m a traditionalist like that,” says Bradfield when asked about the first songs that gelled and began to feel like the beginning of the album, when they thought they might have something.

“So, when we got Decline And Fall down, I remember thinking: ‘Okay, we’ve got a candidate for the first single,’ that Skids vibe to it. Then when we put People Ruin Paintings together, I realised that we were coalescing around something a bit more thoughtful. So between those two was when I’d say I thought we had something to build on.”

While Wire has taken to lead vocals with relative zeal (‘zeal’ is doing a lot of heavy lifting in that sentence), Bradfield, who showed flashes of lyrical brilliance on his solo album The Great Western, and then practically ignored the whole discipline for the best part of two decades, delivered three sets of lyrics for Critical Thinking: Brushstrokes Of Reunion, Out Of Time Revival and (Was I) Being Baptised, the latter prompting Wire to remark: “I wish I could have written that.” It was inspired by a day spent in the company of legendary songwriter Allen Toussaint for the BBC programme Songwriters’ Circle broadcast in 2011, recorded at London’s Bush Hall, when Bradfield, Toussaint and John Grant performed and discussed their craft. It was peak introspective BBC 4 fare, but in a good way.

“We did the soundcheck, hung around the dressing room together, went up to his little room, went for a walk with him, spoke to him before the show, after the show. And inside I was like, fuck me, this is musical history, this is the man who wrote Southern Nights – and I fucking love Southern Nights. It makes me feel free, I don’t know why. And he was talking about being young, breaking into the industry, talking without any bitterness, that was the thing. Whether he was talking about the impact of hurricane Katrina or tacit racism, or just what he thought of other people’s versions of his songs, it was just gracefulness personified.

“Later I went searching for some old interviews with him. And he was talking about Katrina, and I remembered he had said something similar to me on that day, about when the floodwater was coming and he was thinking: ‘Were we going to drown or were we being baptised.’ And that duality of the way he was thinking, I love the idea of being able to twist something like that. If you have some kind of faith in something, which I think he did, not that I do, he could actually see the other side of the coin. When I left him I felt as if I’d learned something. I’d learned a new way of dealing with people. Just after half a day being with somebody, you know, that’s a gift.”

Less positive inspiration and more existential crises – which is very Manics - is the chiming Out Of Time Revival, which marries the ebullient – musically, at least – and the rueful beautifully. A song looking for meaning, just as the singer realises that seeking meaning in the everyday might be meaningless.

“We were coming out of lockdown when I started writing that,” Bradfield recalls. “I’d go down to the beach and walk my dog, and each time I came back from the walk there’d be a new line for the song. And I was coming to this realisation as I stood on that beach: why do I put so much pressure on myself to find an answer in everything? I’ve watched too many films and I’m trying to find answers in the wrong places. There’s too much symbolism. This beach hasn’t got the answer, my dog hasn’t got the answer, my brain hasn’t got the answer, the horizon has not got the answer. I’m trying to find hope in all the wrong places.

“I’m trying to learn French, and I’m something of a Welsh speaker now, but that’s some kind of ability. But that has no answer, they’re just things in life. Not everything is a narrative, be pragmatic Welsh, there’s no poetry in this. That’s what the song is about. It’s actually a bit of my dad; come on, fucking dig in. I look back at some of the stuff I learnt and believed and lived my life by, certain tropes, and you think: fuck me, did I waste my time?”

Do you think that’s also partly because of where you are on the journey now, entering the third and final act?

“Yeah, because you realise it’s maths, you know, and we have lost quite a lot of people from around the band over the years, and that continues to happen. We lost a good friend this year. You realise that you have emotions that come out of the experiences, you have hangovers that come out of these moments, the drunkenness of melancholy and sadness and tragedy, but when you come out the other side you actually realise that the race is the prize. You’ve just got to keep going.”

Do you still enjoy the process, do you still enjoy making albums, not least this one?

“Yes. Because we have this place, the albums evolve more now. It’s not like we switch on a light and the sessions start, and sometimes it’s a full week, sometimes two days and sometimes you’re alone or we’re all here. Then we’ll go to Rockfield and disappear from our families and the day to day to finish the process. We are talking about making an album where we just do something with a bit less thought, be a bit more organic, where it’s just us and we go to one place and say we’re doing it and get it done. That would be a different record to this one, but that’s for another time. And you asked if I enjoyed making this album…”

He points at the ceiling conspiratorially.

“He didn’t.”

“It’s not like I was in a fucking permanent crisis,” says Wire, “I just found it really fucking hard work. That’s probably a good thing. You know, sometimes you do get a lot out of that perceived hard work. But it’s just because we weren’t together that much, and again, it’s worked in our favour. There’s an energy on this album which has probably come through a bit of friction. But, you know, you spend a lot of time analysing how things work or don’t work, especially with us, and sometimes it’s the friction that works for you. I mean, bizarrely, The Holy Bible was an absolute dream to make. We were completely zoned in on the same page. You know, brutally rehearsed, there was no winging it at all. You can’t with an album like The Holy Bible. It was just fucking great.”

Was Richey okay then?

“Yeah, he was, to be honest. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy as the year went on. We’ve done a lot of our growing up in public, made our mistakes too, but took our audience with us. We’ve suffered at times with that. Which is understandable because our extremes are, you know, extreme. But it’ s unbelievably rewarding now when you see the audience and you know they’ve got their kids with them, kids who are Manics fans too, coming full circle.”

Critical Thinking is out now via Columbia