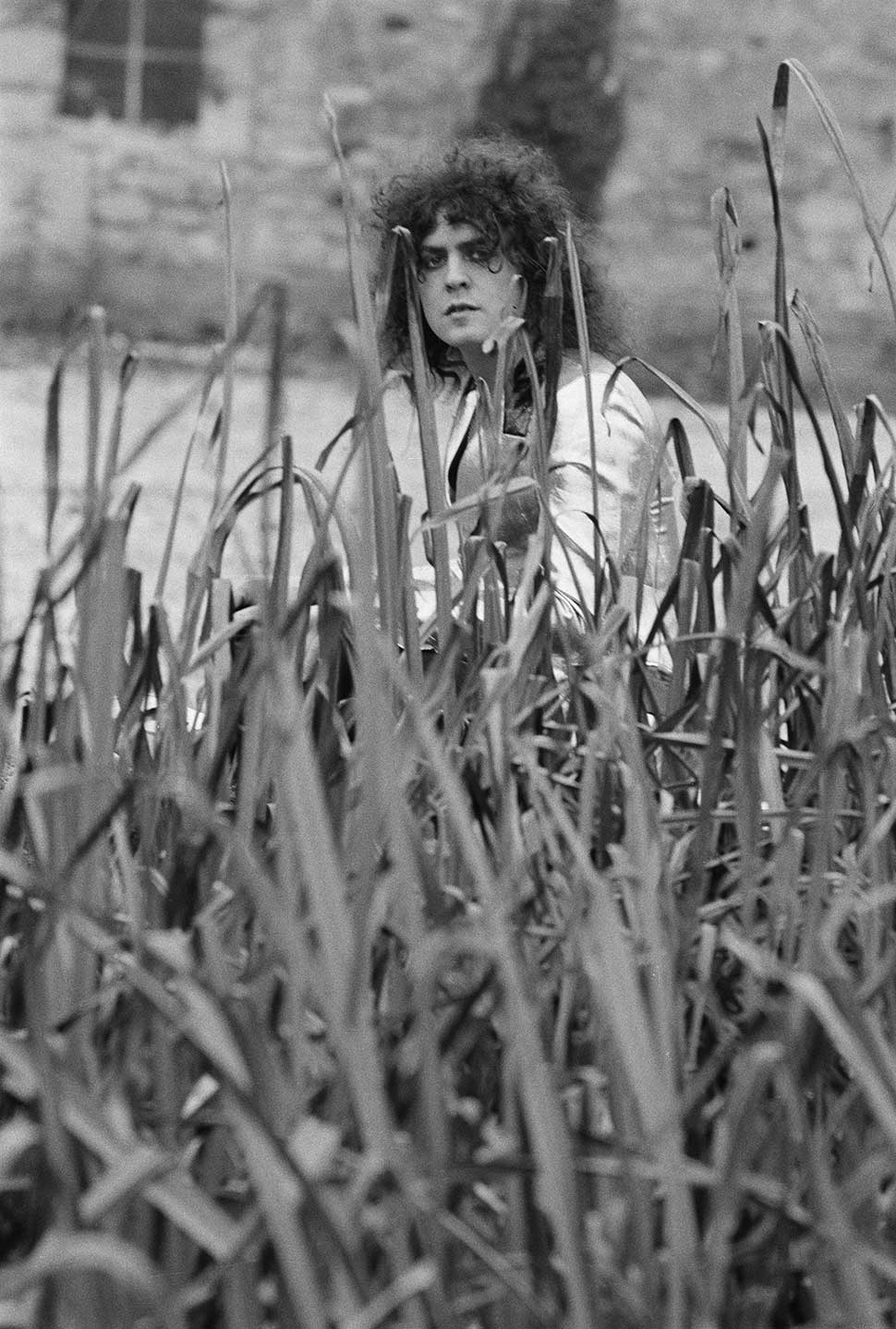

“You see, my idea of rock’n’roll is… that subterranean homesick blues feel,” said Marc Bolan. “Surrealistic rock’n’roll. That’s what I like, that’s what I’ve always wanted to do. I think I got close to it when I wrote the line ‘cloak full of eagles’. It’s a great idea – you open up a cloak and it’s full of eagles…”

‘You should never ‘You should never meet your idols.’ If that’s not a saying, an adage, a maxim, a motto… then it damn well should be. Of course, meeting an idol is an occupational hazard when you’re a rock journalist. No names mentioned, but the reality more often than not fails to live up to your fantasy. A face-to-face encounter with an idol can be a deflating, sobering, even depressing experience.

One of the rare exceptions was Marc Bolan. I only ever interviewed him once. But it was an occasion I’ll never forget. It was November 1975 in the offices of Tony Brainsby Publicity, shortly before the release of the Futuristic Dragon album. Not one of Marc’s best-known works, admittedly. But with his days as the teen-scream Guru Of Glitter well behind him, with the great ship T.Rextasy lost off the misty coast of Albany, he needed the press. And I, in turn, embraced – better make relished – that the chance to talk to my schoolboy (it’s that word again) idol.

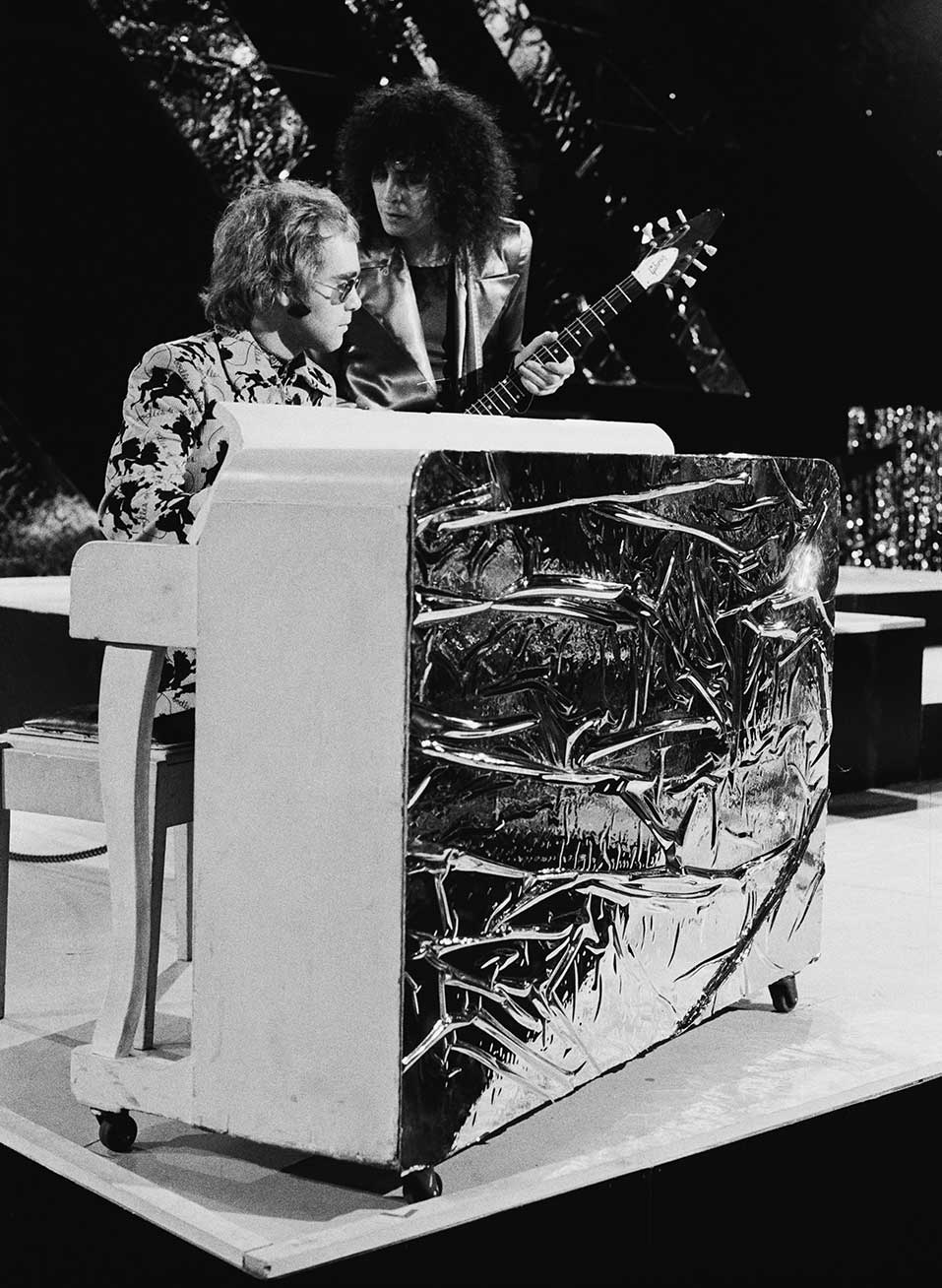

Bolan looked coolly confident, well accustomed to the experience of The Interview. Hair tinted with wispy gold and blue hues, he sported large square spectacles, presenting a somewhat bizarre cross between Cliff Richard conservativeness and Elton John outlandishness.

But hold on. Wait a minute. Did I detect some slight nervousness, a little apprehension behind those lenses? Was Bolan, after all this time, still dubious about talking to the press?

“No, not at all dubious, not in the least,” he said in reassuring tones. “When I started out with Tyrannosaurus Rex the press were always very good to me – no one ever understood me, but it was quite nice, they helped to give me exposure. Then Ride A White Swan [Bolan’s 1970 hit single] happened and suddenly I was very sellable. It was very fashionable to use my face on the cover of everything.

“I still think that, regardless of what anybody writes in the papers, it’s good to have the space,” he continued. “I’ve always got something interesting to say as long as the right person asks the right questions. Alright, so I went through a period of time when I didn’t want to say anything in the papers, but I think every artist goes through that…"

In truth, Bolan had gone through a very problematic period of time. He was only now attempting to reassert his mercurial talents, and re-establish his popularity.

He had fallen a long way. At the height of T.Rex’s popularity in 1971 Bolan had had two No.1 singles (Hot Love and Get It On) and a No.1 album, Electric Warrior, an all-time classic full of cosmic boogie, slinky sex, unmitigated raunch – and rounded off by bucketloads of pixie charisma. Oh yeah, and there was a No.2 single that year as well: Jeepster.

‘Life’s a gas… I hope it’s gonna last,’ Bolan crooned at the peak of his fame. Unfortunately, it didn’t. In June 1973 he proclaimed: “Glam rock is dead.” In spring 1974 he quit Britain to binge on cocaine and booze, and, in thrall to his new love, American singer Gloria Jones, try his hand as a soul-music producer in the States. Now he was back in Britain, his explosive mouth on overdrive, fit, healthy and strutting the Beltane Walk again. At least, that was the plan.

Bolan certainly talked a good fight. “People were saying that I was done for even from the time when Debora [Tyrannosaurus Rex’s 1968 single] came out,” he told me. “A lot of people like what I do, a lot of people don’t. Success has its degrees. Through 1971 and 1972 I was much newer and fresher than I am now, and I hit a big peak. Now I’ve levelled out. I’m still here.”

As our interview progressed, it took on a jumbled, disorganised, almost stream of consciousness quality. Bolan’s mind was brimful of new projects, some completed, several half-finished… but most of which never saw the light of day.

All the same, I listened intently, half in awe of the man, half in bemusement at his agitated blathering.

“…I played the first Tyrannosaurus Rex album recently and then I wrote about 10 songs in the same style, just to show myself that I could still do it…

“…‘The high woods filled with the bones of broken gods.’ I wrote that the other day, it’s a lovely line, isn’t it…

“…I mean, how can I honestly sit down and think that in the past I’ve been compared to David Cassidy? I’ve written some great lyrics, and people say it’s all mindless garbage. Why, even William Blake would have grooved to my lyrics, you know…

“…I’ve got a great story called Future Man Buick, which is incredible, it may be done as a movie. I haven’t been into cars for years. I’ll have to get back into cars…

“I might be doing something with Marvel Comics. They might be using one of my characters. I talked to Stan Lee, the head of Marvel, when the Conan The Barbarian weekly comic first came out in Britain. Stan doesn’t really like Conan that much, did you know? My Electric Warrior character was meant to be a sort of Conan, actually, except that he didn’t follow the conventional boring barbarian pattern…”

Bolan rambled on, going round and round in ever-decreasing circles. But at the same time, he was strangely compelling. His mind seemed to be travelling in a million different directions at the same time. “I’m afraid it is,” he admitted. “I’m afraid it is. That’s the problem with me, you see. I’m a lunatic.”

Despite Bolan’s bravado, Futuristic Dragon only reached a feeble No.50 in the UK album chart. The scale of the task ahead was rammed home when, on May 3, 1976, Marc and Gloria Jones went to see David Bowie play Wembley’s Empire Pool. Four years earlier, Bolan had headlined the venue himself.

“When David started singing he and Marc forged a great friendship,” recalls Jones today. “Then came the rivalry, but their camaraderie never really diminished. David loved Marc very much, and Marc loved David.”

After being friendly glam-rock adversaries, the pair’s careers veered off in radically different paths. By spring 1976 Bowie had re-energised himself as the über-suave Thin White Duke and was playing six sold-out shows at the aforementioned Empire Pool on his Station To Station tour.

Bolan, by contrast, was being lumped in with likes of Alvin Stardust and Showaddywaddy. He had been reduced to playing London’s Lyceum Ballroom on his Futuristic Dragon tour in front of just 1,000 people. The tour was a supposedly low-key one, hence the undersized attendance. Still, that didn’t stop Melody Maker describing Marc as a ‘faded old tart’ in a live review.

Bolan’s long-time record producer Tony Visconti recalls the battle with Bowie: “They saw each other as competition right from the start. But they were such contrasting personalities. Marc was a rock’n’roller, and his other passion was mythology. He loved Tolkien’s stories, but Bowie had no interest in them at all. Marc bought me The Lord Of The Rings and said: ‘If you want to know more about me, read this.’”

BP Fallon was Bolan’s publicist at the height of his charge’s fame. Fallon invented the term ‘T.Rextasy’ and was immortalised as ‘purple-browed Beep’ in Telegram Sam. He offers his perspective on Bolan versus Bowie: “Yes, Marc was a rock’n’roll boy. David was, and indeed still is, an artiste with an ‘e’ at the end. David can put a Kabuki painting to music, but for all his brilliance he’s not a get-down rock’n’roller. #

"That’s what people forget about Marc. To see him on stage playing his guitar, laughing and singing… now that was rock’n’roll, y’know? He had that tease, he had that sexuality, and he had a real sense of fun. T.Rex records worked so well because they were celebratory and a bit cheeky at the same time.”

But a failure to reinvent himself as successfully as Bowie cost Bolan dear. As Visconti explains: “Marc found a formula that he stuck with, which in the end didn’t serve him well. He started to evolve toward the end of his life, but it was too late. He was a little afraid. You can imagine he was so heady with the success of T.Rextasy. He was afraid to let go.”

You can see why. When Tyrannosaurus Rex morphed into T.Rex, mystic aura and attentive audience (small) was replaced by wild sexuality and riotous audience (large). A few ‘heads’ grumbled the words ‘sell’ and ‘out’, but Bolan left them for dust.

“What actually gets forgotten is how uptight a lot of strait-laced people got with Marc’s behaviour,” BP Fallon reflects. “Here was a guy with glitter on his cheeks, wearing gold shoes. And tights. Is it a boy? Is it a girl? People got as weirded-out with Marc as they did with Bowie. I remember one Top Of The Pops where Marc was wearing a toy plastic Roman breastplate that he’d bought in Woolworth’s – and one of his nipples was showing! It caused outrage.”

While it’s true that the hits never totally dried up for Marc Bolan, there’s little doubt his creative muse fizzled rather than sizzled in his latter years. Steve Harley, the Cockney Rebel frontman and close confidant of Marc’s, states of Bolan’s later work: “It was just fifth-form poetry. It didn’t mean anything. He gave up writing proper poetry once he realised he could be on every girls’ bedroom wall with Ride A White Swan onward. His earlier work was a joy to behold – A Beard Of Stars [Tyrannosaurus Rex’s 1970 album] is a classic, it’s in my Top 20 of all time. But Marc got a little bit lazy later on.”

Bolan’s June 1976 single, I Love To Boogie, was more of a simplistic chant than a cast-iron classic. Nevertheless, it heralded a comeback of sorts, reaching No.13 in the chart. The relative success of I Love… led to a one-off TV special, Rollin’ Bolan. And then, much to Bolan’s delight, he was offered a TV series all of his own, simply titled Marc.

Steve Harley takes up to story: “Muriel Young kick-started it all. She was a kids’ TV presenter – she used to work with a puppet called Ollie Beak, remember him? – and then she became a TV producer. She offered Marc a teatime TV series. And he was very excited – as you would be. He saw every little appearance on the small screen as making him more famous in Sainsbury’s. Marc loved it all. He loved all the adulation and the recognition. He thrived on it.”

“Marc was grateful to have a second chance,” says Tony Visconti. “He loved kids and he loved kids’ TV shows. That was how Geoffrey Bayldon [the actor in Catweazle] got a part in the Born To Boogie movie. Marc was back on form. He was the cosmic punk again.”

Talking about punk, Bolan was one of the few mainstream music stars not to be horrified when Babylon began to burn. Indeed, many of the burgeoning bands of the day such as Generation X and The Jam guested on Marc.

“I was at the Weeley Festival in 1971, where Marc played. I think I was still a schoolboy, actually,” recalls Captain Sensible of The Damned. “It was amazing, because Bolan had just had his first big hit single. He went on stage and I’ll never forget what he said: ‘Hi. My name’s Marc. You might have seen me on Top Of The Pops.’ It was absolutely brilliant. Total class.”

On Bolan’s final British tour, promoting his 1977 album Dandy In The Underworld, he invited The Damned to join him on the road as T.Rex’s support band. “Marc was firing on all cylinders,” Sensible recalls. “He’d got rid of his drug habit, he’d gone through his arrogant stage, he was almost humble. He was getting fit, the cheekbones were coming back, he was excited, he had a great band, and the songs were getting better.”

However, Steve Harley believes Bolan’s endorsement of punk was purely a means to an end. “He would seize any opportunity to further his own career. The Damned weren’t bona fide punks, anyway. Marc would’ve embraced any movement as long as it reflected well among the gullible.

“I say this with no criticism and no malice, but Marc was a fully paid-up member of the Fantasy Island Club. He’d just make things up. I was on the same label as him, EMI, and he’d say: ‘Oh yeah, my new single, it’s done 30,000.’ And I’d say: ‘Marc, I’ve seen the figures. It did 3,000.’

“Marc had to talk everything up. Why tell the truth when an exaggeration would do? Bless him. I mocked him, constantly. I ribbed him. I adored him and his crazy madness.”

Marc Bolan’s mini-revival ended abruptly in the early hours of Friday, September 16, 1977.

The night before he had been at Morton’s restaurant in London’s Berkeley Square, celebrating Gloria Jones’s return to the UK from California, where she had been recording an album. Marc had been drinking heavily for most of the day.

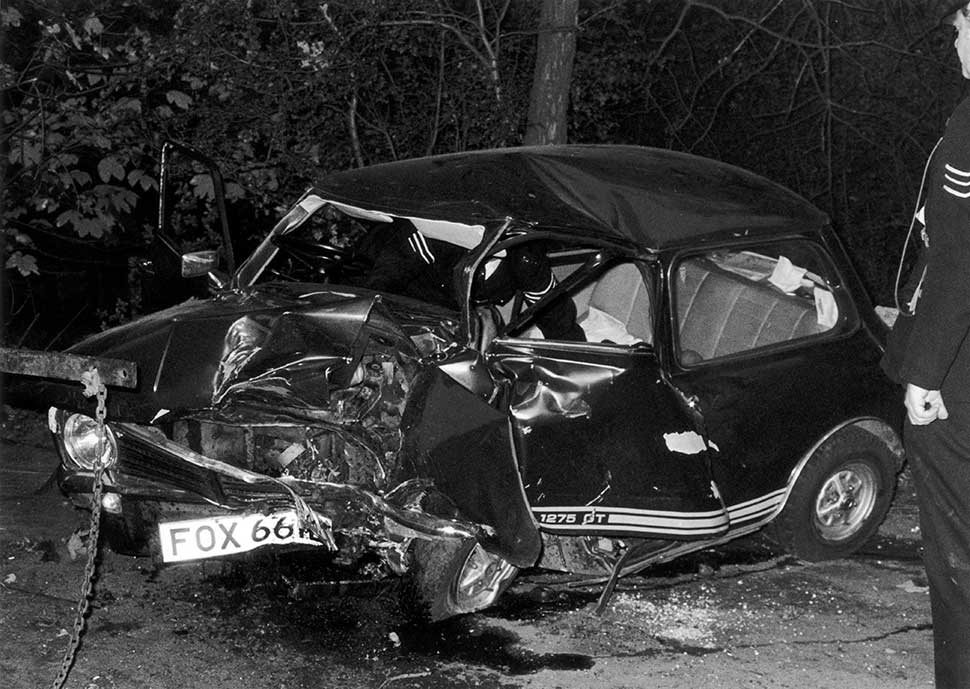

Bolan and Jones left Morton’s at about four o’clock in the morning in a purple Mini 1275 GT. Jones was driving. The pair headed to their house in Upper Richmond Road West, East Sheen. A little before five o’clock the car left the road at Queens Ride, Barnes Common, and crashed into a tree. They were barely a mile from home. Bolan was killed – his seat swivelling through 180 degrees and ending up in the rear of the vehicle – and Jones was severely injured.

To the best of Classic Rock’s knowledge, Jones has never spoken publicly about the smash.

“We don’t need sensationalism right now,” she states plainly. "If people still want to speculate about the manner of his death, fine. But right now let’s look on the positive side. It was a long time ago. We need to move on now.”

It has been alleged that Jones was drunk at the wheel but one source who does not want to be named, but who was close to Jones at the time, refutes this: “Gloria had a lot of self-control. She had a very clear-minded American outlook in that respect. She was the type to have one drink, then call it quits and not have any more, because she wanted to stay in control of her faculties.”

The spotlight fell on the Mini, which had recently been serviced. Its wheels had been balanced and a tyre had been replaced. As Mark Paytress noted in his book Bolan – The Rise & Fall Of A 20th Century Superstar: ‘When the Mini was examined after the accident, the pressure on the offside front tyre was only 16lbs, 12lbs less than it should have been; one of the rear tyres was marginally down; and two nuts on one of the front wheels were not even finger-tight. There was also talk that the vehicle may have been one of several used by Pink Floyd’s management company, and that it had been “souped-up” in accordance with the band’s thirst for high-speed motor racing.’

“I was in Los Angeles when it happened,” Steve Harley recalls. “The managing director of EMI, Bob Mercer, phoned me up. My tour manager and I were on the first plane to England. I knew that, with Marc being Jewish, the funeral would be very quick. I came back and went straight to the hospital to see Gloria – she had facial injuries and her jaw was all wired up.”

“I was in Berlin working and I immediately flew home for the funeral,” says Tony Visconti. “It was such a jolt that I had to find the nearest place to get a drink. I remember gulping down about three shots of something just to handle the news. My PA back in London said: ‘The journalists want a quote from you.’ I went: ‘A quote? I can’t think, I don’t have anything to say. It’s a tragic loss.’ I came up with something stock. I couldn’t gather my thoughts. I couldn’t even believe he’d died.”

“I was sitting out in my garden. It was a sunny afternoon, if I remember rightly,” says Captain Sensible. “I was living with my mum and dad. Terrible isn’t it – don’t tell the press! We had a little semi-detached in Croydon. My mum came back from the shops and said: ‘Your pop-star mate, Roley or Boley or whatever his name was, has died.’ I said: ‘Not Marc Bolan!’ I ran round the corner, got an Evening Standard, and there it was. It was true.”

BP Fallon visited the crash site in Barnes personally. “I got a phone call in the morning from my friend Fachtna O’Kelly, who was the manager of The Boomtown Rats. He said: ‘Have you heard the radio today? Marc’s dead.’ It was unreal. Elvis had died not long before, and I was round Marc’s house when the news broke. Marc said: ‘Do you know what? I’m really glad I didn’t die today because I wouldn’t have made the main story.’ When Marc died I think it was the same day as Maria Callas – he got the main story, thank goodness.

“But when you think about some of Marc’s phraseology… ‘Tyrannosaurus Rex – eater of cars.’ ‘Hubcap diamond star halo.’ ‘Seventy-seven is going to be heaven.’ [The latter being a line from Bolan’s final single, Celebrate Summer.] It’s all writ. It’s all known.

“So I went to the tree. The tree the Mini had run into. There was all this glass on the ground; nobody had bothered to clear it up. Already people had started leaving notes and messages. There was no one there apart from me. Then this girl appeared. She was gorgeous. I found myself chatting her up. I could imagine Marc saying: ‘For fuck’s sake, there he goes, he’s standing right where I died, by the tree, and he’s chatting up a bird.’ People may lose their physical continuity but it doesn’t mean you have to lose them.”

In contrast to BP Fallon’s somewhat spiritual outlook, Steve Harley refutes any claim that Bolan had a death wish. “Oh, no. People talk such bollocks. You can’t believe a word of that. He was never going to burn out, Sid and Nancy style. Not a chance. He was grounded in many respects. Marc wanted to live forever. He lived for the day. He loved life. He never thought he was going to die young. No one thinks they are going to get wrapped around a fucking tree in the early hours of the morning. Nobody could have foreseen that.”

Estranged wife June Bolan (née Child) went to pay her respects to Marc’s dead body. “She told me his face looked so beautiful and he had one little mark over his eyebrow,” says Tony Visconti. “That was the only indication he’d been in an accident. She couldn’t understand how that had killed him. Just one tiny little mark.”

Marc Bolan’s funeral took place on Tuesday, September 20, 1977 at Golders Green Crematorium. David Bowie and Rod Stewart were in attendance, as were Steve Harley and members of The Damned. Elton John sent a bouquet. The centrepiece was a huge white swan made out of chrysanthemums. According to Visconti, who was there with his wife Mary Hopkin, the occasion turned into a circus.

“It was a Jewish ceremony. There was a rabbi reading a eulogy, and Marc’s coffin was in the middle of these twin tracks, like on a railroad. The eulogy was beautiful, and then this funereal music started up on the organ. A big robotic arm appeared out of a crack just in front of the coffin and moved it along the rails. A pair of doors opened up like the mouth of Hades. There were flames bursting out in front of us. At that moment Marc’s mother just shrieked: ‘My boy!’ I started crying and everyone lost it.”

What would Marc Bolan have done next?

No one can quite agree on what exactly Marc Bolan would be doing today, if he’d lived.

Gloria Jones: “He’d be doing his own music, he’d be doing film, he’d be enjoying time with his son, and we’d possibly be living in Malibu. Because that was the plan. He would be good-looking and still sharp.”

Tony Visconti: “I think he would have acted. I think he would have written a film. I think he would have stretched out into other fields. We were working on this rock opera called The Children Of Rarn, and I was dying to get back to him and do that one properly. The demo was put out posthumously, and it had all the signs of a great work. But Marc never got around to doing it properly. His pitfall was always: ‘Let’s just do one more for the kids.’”

Captain Sensible: “Crikey. I don’t think I’ve any idea. That’s the amazing thing, isn’t it? You think, what would Jimi Hendrix have done if he’d lived? If Paul McCartney had died and John Lennon had lived, what would’ve happened then? It’s really tough to answer.”

BP Fallon: “He’d be writing fantastic books. He used to write wonderful stories, but I don’t know what happened to them. Magical stories, in that peculiar handwriting of his. And maybe acting, too.”

Steve Harley: “The world was a mirror to him. He couldn’t walk past a shop window; he couldn’t walk past a fucking bus stop without looking at his reflection in the glass. But I adored all that. So I miss him to this day. I can say that in absolute, total truth. I’m talking about him as if I can see him now. It’s a very strange feeling.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #111, published in October 2007.